Sometimes museums keep the coolest stuff out the back where you can’t see it.

It's not a personal thing.

Sometimes it's space issue: The Natural History Museum of London has 80 million specimens in its collection, so it makes sense that there's over 20 million of them kept in various rooms out the back.

This is the Spirit Room.

They've got an actual giant squid back here and her name is Archie. (She's in the tank in the middle.)

They keep loads of other dead things in jars here – some are hundreds of years old, others have just arrived.

There are bizarre and hideous deep sea fish, prehistoric-looking sharks, komodo dragons, manta rays, massive lizards, huge octopuses, monotremes, mammals – everything you could think of, including a jar of monkeys.

When specimens are too big to fit in the glass jars, they go in the metal tanks in the centre of the room – enormous lidded baths of industrial methylated spirits where they lie flopped against each other for decades.

It’s a constantly growing collection. If something weird washes up on the shore, the Natural History Museum wants to know about it.

The room has been used as a backdrop in TV shows like Silent Witness and various David Attenborough projects. It’s the setting for a scene in Paddington, although in that it's populated with fake things in jars because they looked more realistic on film.

(Or something. Fish curator James Maclaine – who spent all night on set making sure nothing got smashed – is not really sure why the producers brought their own stuff in jars to fill a room full of stuff in jars.)

Blue Velvet actress Isabella Rosselini has visited here, as has ex-Velvet Underground musician John Cale. “John Cale was bored out of his mind," Maclaine says. "His girlfriend was trying to get him to look at stuff and he just didn’t care. He was releasing an album that had pictures of bones on it. There’s a picture of him lying on a table in here, but this place just didn’t do anything for him.”

The Queen came and saw it too. She wasn’t all that bothered either. “There are some pictures of her looking really disgusted at various things. She’s clearly wondering how much longer it was going to go on.”

There's a bunch of reasons why the Spirit Room exists and why you can only see it on a tour, but none of those reasons are “famous people apparently aren't into it”.

Firstly, there’s the health and safety thing: The specimens are preserved in spirits (hence the name) so need to be kept in a room that is specially designed to vent any flammable vapours, a variable that couldn’t be controlled in the main hall of the big old museum.

There’s also the fact that some things are just too massive to be wheeled out and put on show: Archie the giant squid, together with her bath of alcohol, would go straight through the floor museum’s old floor.

But mostly it’s because this is a research collection – a library of dead things – and scientists are constantly hauling stuff out of the baths for research (a tricky job to do among the school groups and tourists in the main hall).

Designers from Speedo came here and observed tiny squares of shark skin to help design their hydrodynamic Fastskin swimsuit for the Olympics (the sharks now have tiny squares missing from their skin). Scientists doing postmortem work on victims recovered from an air disaster at sea came here to work out who had been eating the bodies in the water. There have been architects, engineers, artists, and historians back here.

So you never know what someone might be working on when you interrupt them on your Spirit Collection tour.

Maclaine and Jon Ablett (mollusc curator) have worked here for years, so they introduced me to a bunch of guys they've got floating around in those tanks.

This is a frilled shark from the deep sea:

Usually the deeper you go, the weirder things start to look, Maclaine says. “We got this specimen in 1961, which is pretty young. Most of the things in here are over 100 years old.”

This is a baby ocean sunfish:

It’s huge, but still tiny compared to the massive three-metre giants they become.

“When you’re preserving things you can’t just put them in preservative – you have to preserve the inside as well," says Maclaine. "So we either inject them or open them up so the preservative can get inside. When we opened this one up, it had a tapeworm that was three metres long. It just kept coming out and out and out. It was disgusting. If it’s a strange fish it’s going to have strange parasites which researchers will want to know about.”

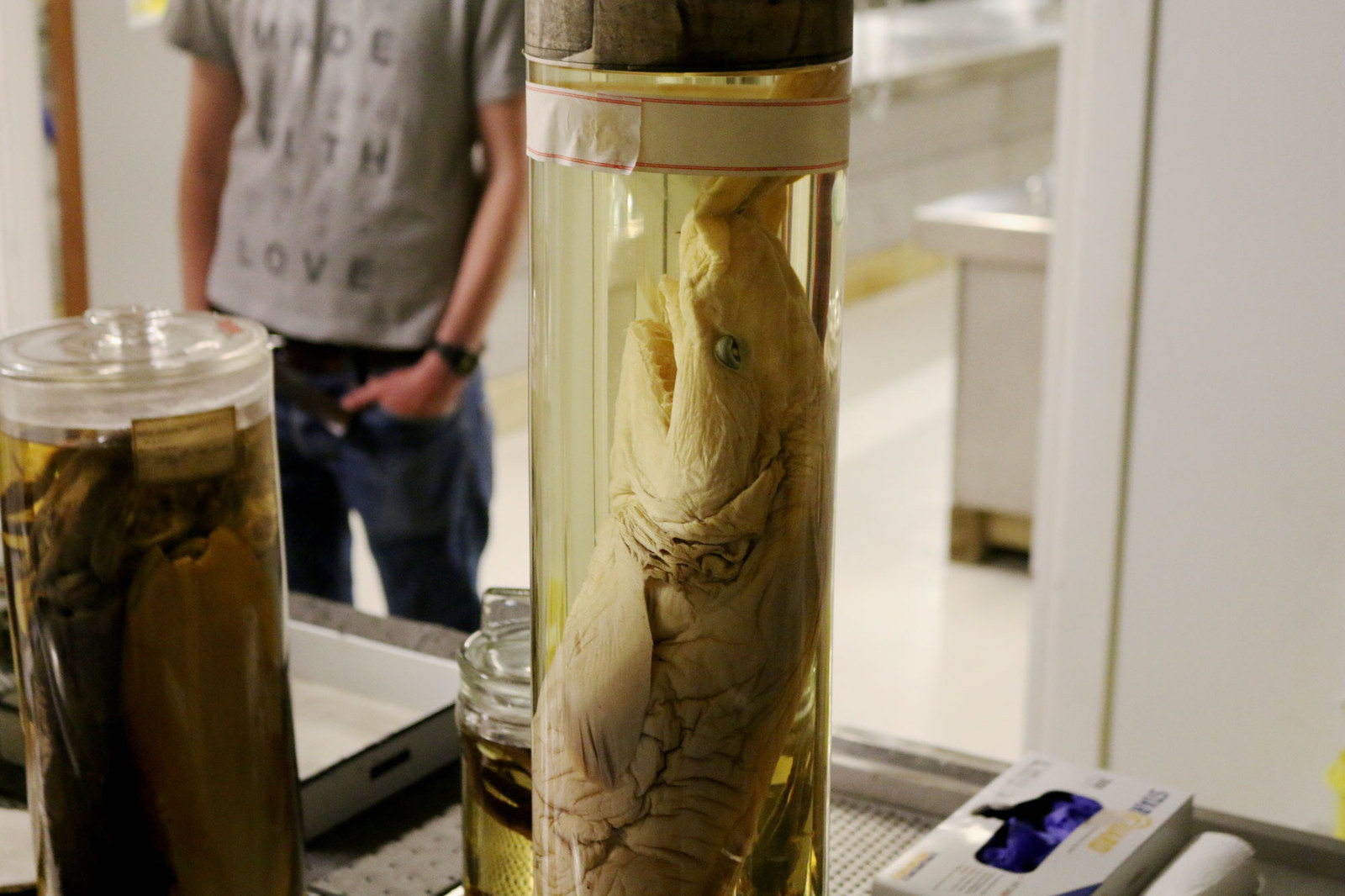

This is a monkfish, a kind of anglerfish. We, uh, eat these.

“It likes to sit on the seabed pretending it’s an old bit of rubbish with seaweed growing on it," says Maclaine. "It has a little flap of skin at the end of its fishing rod which it just twitches around and attracts the attention of fish. Then they come over and this enormous mouth opens up and sucks them in. It’s even got teeth on its tongue.”

Bears repeating, really: It's even got teeth on its tongue.

This guy ate another guy and became massive:

“This is a hairy anglerfish," says Maclaine. "I put it in a CT scanner to see if I could find out what it was inside it and it’s got a whole other fish curled up and folded up on itself."

This is another kind of anglerfish:

Small enough to fit in a jar.

Here's what's going on inside a shark's mouth:

"What this shark does is it bites holes in things," says Maclaine. "It goes up to something like a tuna or another shark or even a whale and it grips and scoops and spins round and pops out again."

(Sort of like a melon-baller.)

"There was a long-distance swimmer in the Pacific that got attacked by it. It spends the day quite deep down, I think this one was from below a thousand metres, but comes up at night. And this guy who was doing a swim turned on a light to summon a boat and it attracted loads of different animals. Next thing you know something was biting his leg, and when he got on the boat he had this hole in his calf muscle from this guy."

In a cupboard by the door are specimens collected by Charles Darwin on the voyage of the Beagle back in the 1830s, one of the most important scientific expeditions in history.

No, really. It was various discoveries he made on this trip in South America that led to his theory of evolution.

One of the things Darwin collected was what became his pet octopus:

“He collected it in the Cape Verde islands," says Ablett. "He actually wrote in his diary how he watched it scuttling amongst the rock pools. The ship’s captain, Captain Fitzroy, said Darwin was like a child on Christmas morn playing with the octopus. He kept it alive for a few days in a tank onboard the boat. And then it ended up here.”

The octopus is sliced down the middle because, like everything in the collection, it's available to be dissected and examined.

Most of the Darwin collection have yellow lids, which means they’re “type” specimens – the very first instance of that particular thing being collected by a scientist, the one that’s used to describe the whole species.

Darwin didn’t know about everything he was collecting at the time, he just bottled them and they were identified later by a guy called Leonard Jenyns, who wrote them all up in a book.

Right near all of Darwin’s stuff are the bottled furry mammals, including the unnerving jar of monkeys that people tend to fixate on.

During tours, the conversation about why we have to kill stuff for science tends to come up – usually here around the mammals, because furry animals are more emotive to humans than a fish.

Maclaine says they don’t actively go out and hunt stuff any more, especially not mammals, although they do collect live snails.

“In order to really help the animal, you have to understand it," Maclaine says. "And in order to understand it you have to look at them and see how they work.

"In order to do that, you need to have one or two dead ones.

"And these ones are here forever.”