Australia keeps refugees and asylum-seekers in offshore detention centres for indefinite periods of time.

The Australian media are rarely allowed on to the tiny island nation of Nauru, just northeast of Australia, where hundreds refugees and asylum-seekers who tried to reach Australia by boat are held.

But the Nine Network's A Current Affair program was recently granted unprecedented access.

There are 468 refugees and asylum-seekers, including 37 children, living in detention centres on the island. Others live in the community.

The wellbeing of the people held in Australia's "offshore processing" facilities has long been a concern for Australian youth, politicians, child welfare campaigners, and traumatologists.

The Nauruan and Australian governments claim conditions on the island are good. But there have been numerous incidents of sexual and physical assault of detainees, and refugee advocates maintain the island's foreign inhabitants live in inhumane conditions.

Hundreds of single males waiting to be resettled into the community live together in tents that are covered in mould, A Current Affair reported.

"They're very, very much well looked-after," Nauruan president Baron Waqa told the program.

"They are welcome here," he said.

"If it's good for the Nauruans, I think its good for our refugee friends and asylum-seekers. We try our best to make it very comfortable for them."

Justice minister David Adeang said refugees made false claims of sexual and physical assault to police.

Between November 2013 and March 2015, 11 security guards at the detention centre were disciplined or fired for sexual assault or use of excessive force, an Australian government inquiry found.

Many refugees claim they are still living in fear from violence.

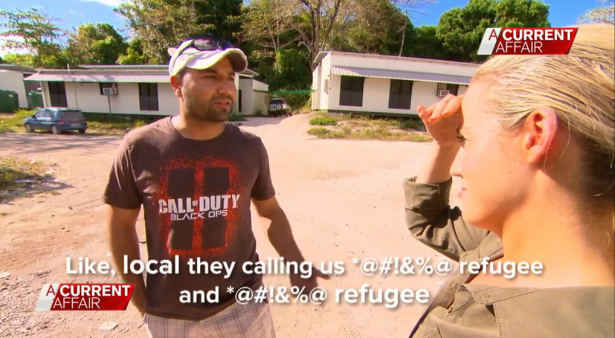

This man, whose wife and children are still in Pakistan, said he did not feel safe to leave his accommodation at night after 7pm because the locals were so hostile.

This refugee said she got married because she felt unsafe around men both at her accommodation and further afield on the island.

She spent two years living in a tent but now has access to air conditioning and a TV.

Refugee children said they were bullied at school by Nauruans.

"They spit in our lunch ... They fight us," this girl told A Current Affair.

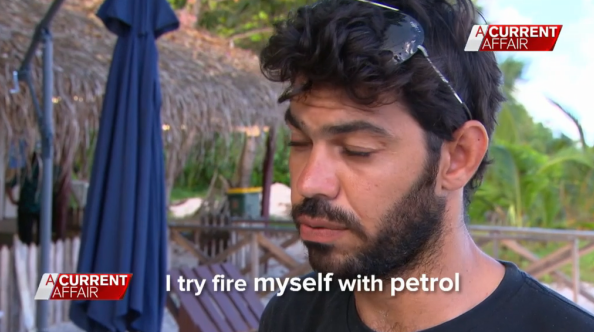

Iranian refugee Mustafa spoke about his best friend, Omid Masoumali, who died in April after setting himself alight, and said he had tried to do the same.

"Because you know I have pain," he said. "After that the police catch me and for one month I stay in jail."

His restaurant might be named after Sydney's iconic Bondi Beach but Mustafa didn't believe the refugees on the tiny island would ever reach Australia.

"Australian immigration or Nauruan immigration have to show us another country [to live in], Canada, Europe, New Zealand, I don't know," he said.

Refugee Hirsi said he was waiting to be resettled in the community on the island but ultimately wanted to be accepted into Australia where he could build a "better life".

"We don't give up."

But other refugees told A Current Affair they no longer wanted to be settled in Australia after the way they had been treated by the government.

"Three years ago I liked [Australia] but now never [would I be settled there] ... because my kids don't like because they have not good memory from Australian government," this man said.

"We don't want to go any more there," his daughter said.

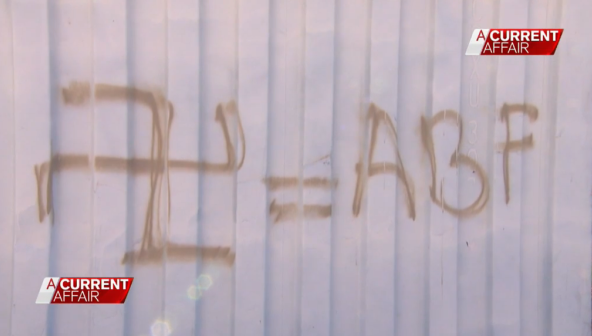

Footage of signs and graffiti linking the Australia Border Force with Nazism showed the distrust and resentment toward the Australian government.