Aldershot’s Safe Haven café sits on the high street in the town centre, tucked between a bookmaker's and a charity shop. Most local residents have probably walked past it without a second thought. But the unassuming NHS outpost has proved a lifeline to the hundreds of people with mental health problems it helps every year.

Kirsty Wray, 39, was one of the first to come here when it opened in 2014. She has been in and out of institutions all her life – growing up in care, in trouble with the police, in and out of secure units and hospital. Her community psychiatric nurse advised her to try something new.

"The first time I walked in, I wasn’t Kirsty with a mental health problem, I was just Kirsty,” she says. "And I was accepted – there was no judgment; I wasn’t my diagnosis. It was something I’ve never experienced before. Somewhere I could talk about what’s going on and somewhere I could escape the struggles of everyday life, really. Yeah, it was a life-changer.”

The café, open all year round, is exactly the kind of project that NHS England is keen to show off. This is the future of the health service, they say: an example of “integrated care” aimed at keeping people out of accident and emergency. Mental health, public health, social care – these are services that can largely be delivered in the community, away from the queues and chaos of hospital.

But the reality is that such glowing examples of care are few and far between. As the NHS turns 70 on 5 July, there is a serious and growing recognition that things need to change, and fast.

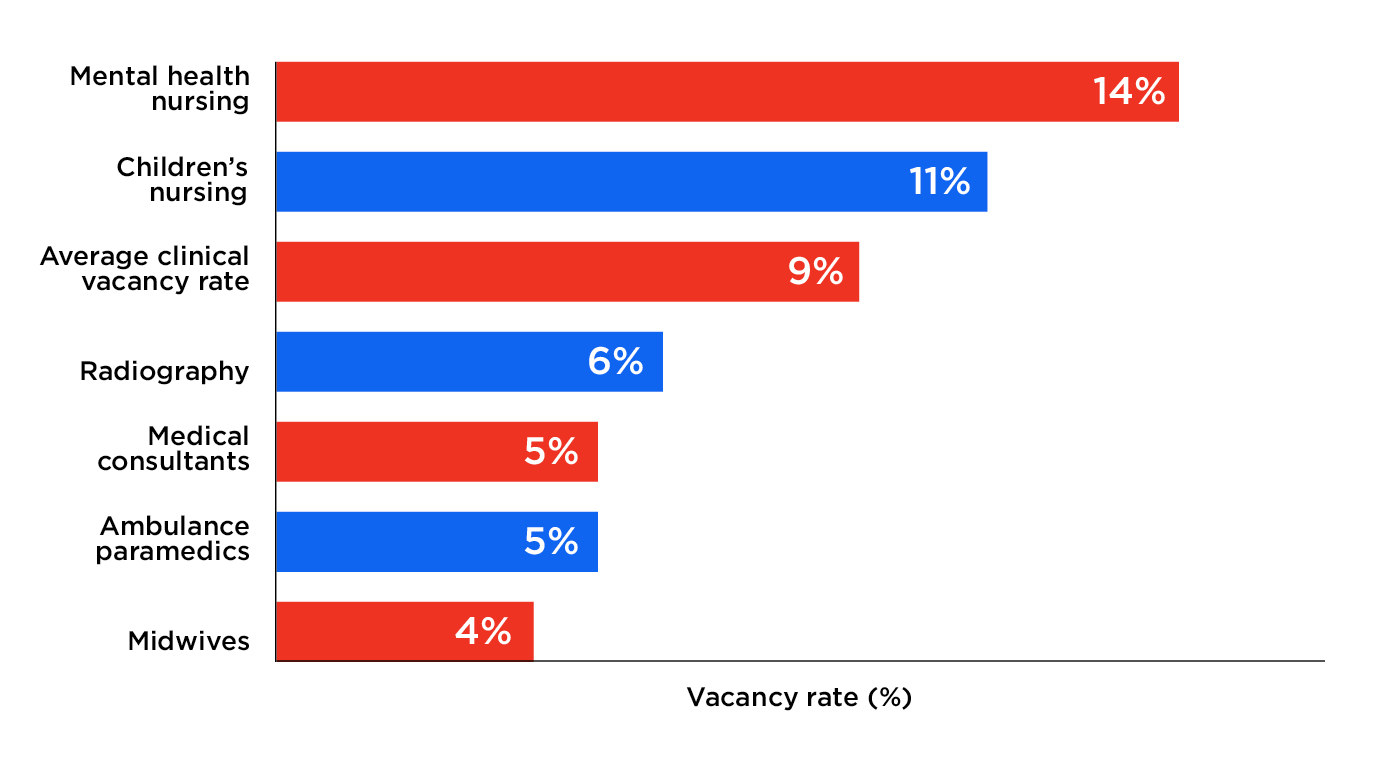

Booking a GP appointment is difficult if not virtually impossible, long-planned operations are being cancelled, hospitals are suffering severe staff shortages, and cancer survival rates are trailing behind other European countries.

Meanwhile, a crisis in social care is seeing older people trapped for months on end in hospital wards, and the long-promised “parity of esteem” between mental and physical health still feels for many like a distant dream.

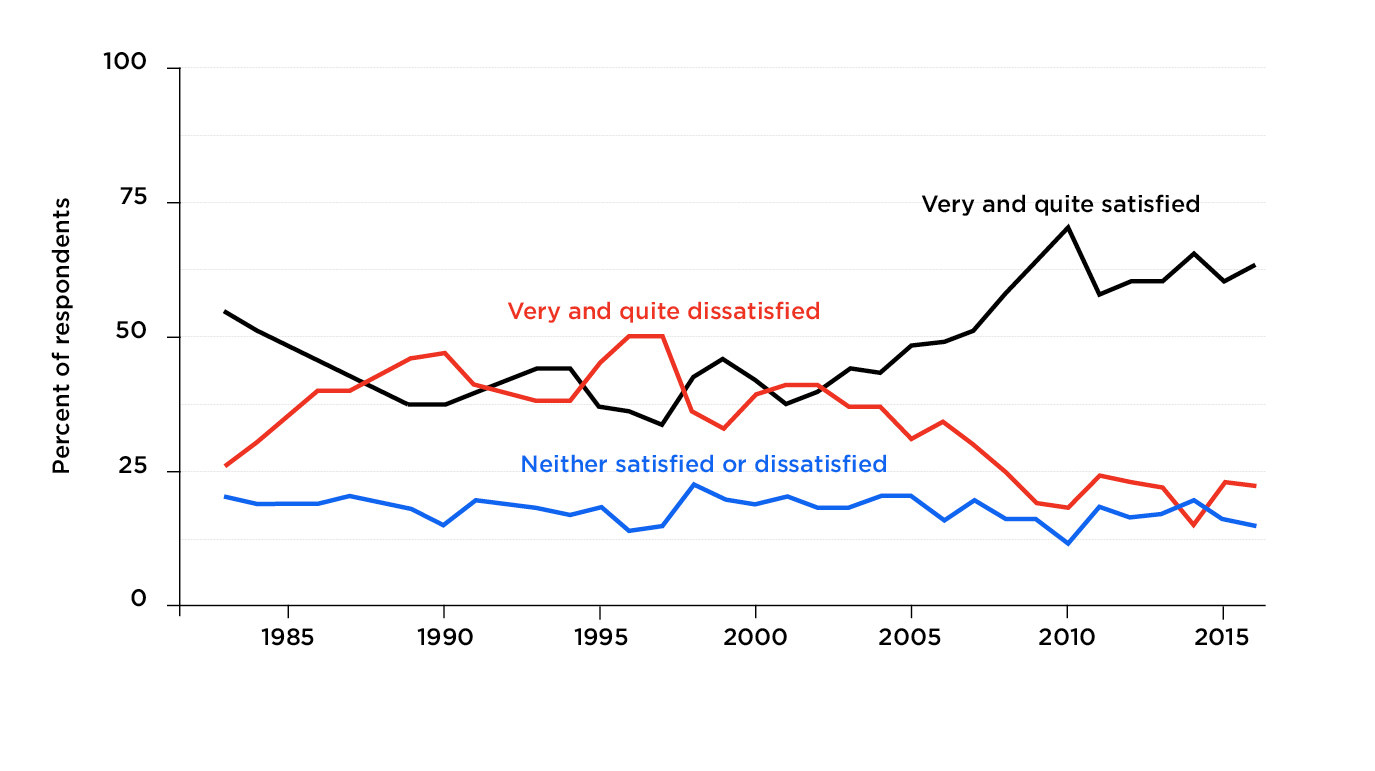

And yet, despite all this, there is an instinctive devotion among Britons towards the NHS that can be hard to square with its clear failings. The health service is where emotions run high – from ecstatic highs to heartbreaking lows – which can make it difficult to have a clearheaded conversation about the big changes potentially required to make it fit for the 21st century.

BuzzFeed News has spoken to leading healthcare professionals and senior politicians, all trying to find a way through the challenges facing the NHS as it enters its eighth decade. The key findings include:

- Health and social care secretary Jeremy Hunt said he was confident that people will overwhelmingly support tax rises to fund the NHS – but hinted that further cuts to the health service were necessary to justify such a move.

- He dismissed calls from senior MPs for a cross-party commission to examine who should pay for the extra funding and how, prompting dismay from health committee chair Sarah Wollaston.

- Former health secretary Andy Burnham spoke of his frustration at the “lack of courage” from politicians to reform social care, saying the Tories’ “death tax” poster in 2010 represented the “worst of Westminster”.

- Shadow health secretary Jon Ashworth warned that England was “in the midst of a mental health crisis for young people”, and said the government’s NHS funding package was just a “PR exercise”.

- Sir Andrew Dilnot, who chaired a major review into social care for the coalition, said there has been “very little” serious political debate about the NHS for the past 35 years.

Last month Theresa May proudly stood in the Royal Free Hospital in north London to announce a birthday present for the NHS – an extra £20.5 billion between 2019 and 2024.

It means health spending will grow by an average of 3.4% each year – further than some thought prudent chancellor Philip Hammond would go, but short of the 4% that experts said was needed at the very least to make improvements.

The money is for frontline NHS services only, not for new buildings or for social care or for public health. The government insists these have not been forgotten – a social care paper is expected in the autumn and a budget for public health will be unveiled in next year’s spending review – but critics believe all this should be considered in the round.

The prime minister claimed the extra funding would be boosted by a “Brexit dividend”, as she seized the opportunity to win favour with Brexiteers in her Conservative party. (The £384 million extra a week is coincidentally very similar to the number slapped on the side of a bus.)

But this was a red herring. As ministers have since admitted, the extra money will have to come from tax rises and borrowing over the next few years at least.

“Obviously there isn’t going to be an enormous dividend in the first two years when we’re in the transition period,” Hunt told BuzzFeed News. “But what the prime minister is saying is what people voted for in the Brexit referendum, they wanted taxes to be spent on public services like the NHS instead of subscriptions to our membership of the EU, and that’s the promise she’s honouring.

“Now obviously we’ve got the transition period, we’ve got the divorce bill, so there’s not going to be a huge amount available in the early years, which is why, yes, the tax burden will have to go up and the chancellor will tell us precisely how in the Budget.”

Hunt hinted at further cuts to the health service in order to better sell tax rises to the public. “If the public see that the NHS has got a good plan to tackle waste and inefficiency and improve productivity and their money’s going to be well spent, then I think they will be very supportive,” he said.

Those cuts were already being spelled out by NHS England this week, as it outlined 17 surgical procedures that could face the axe to save £200 million a year, such as tonsil removals, back pain injections, and breast reductions.

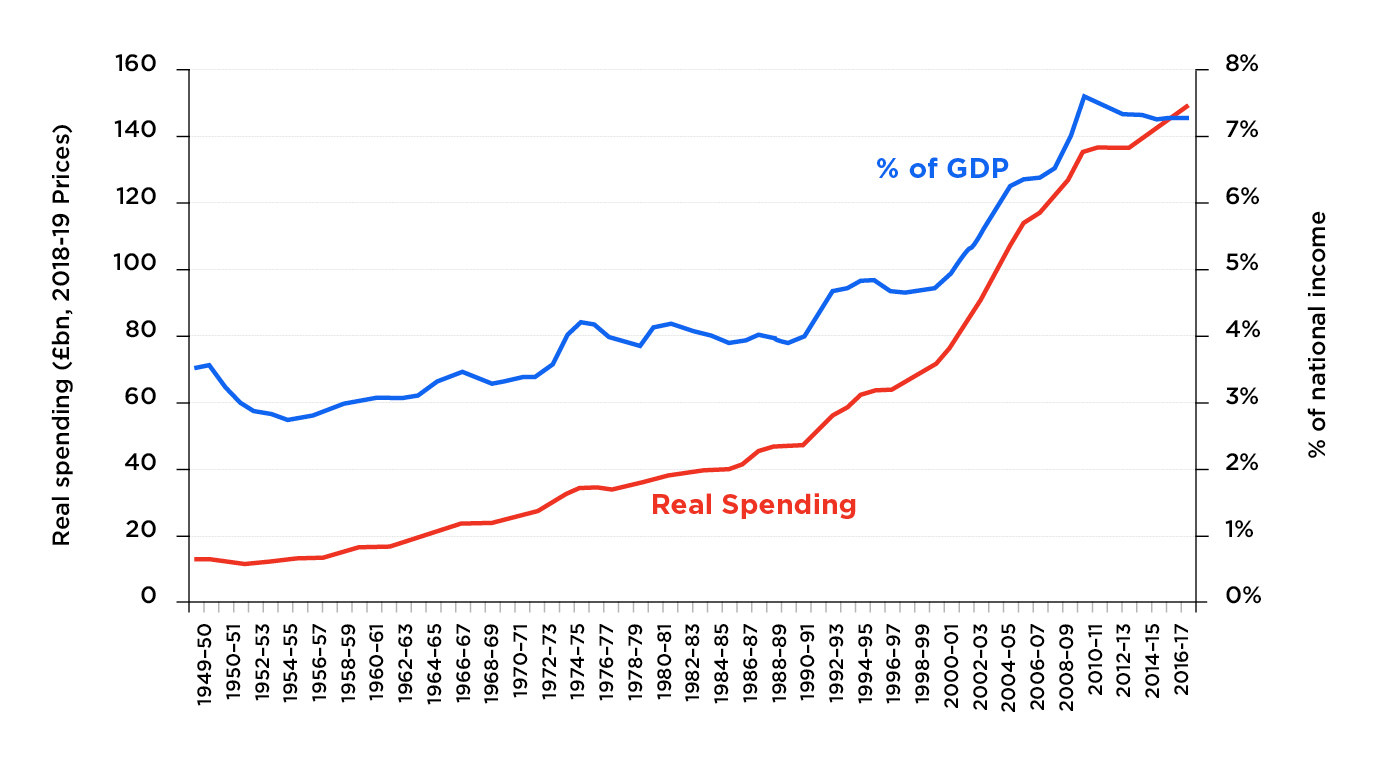

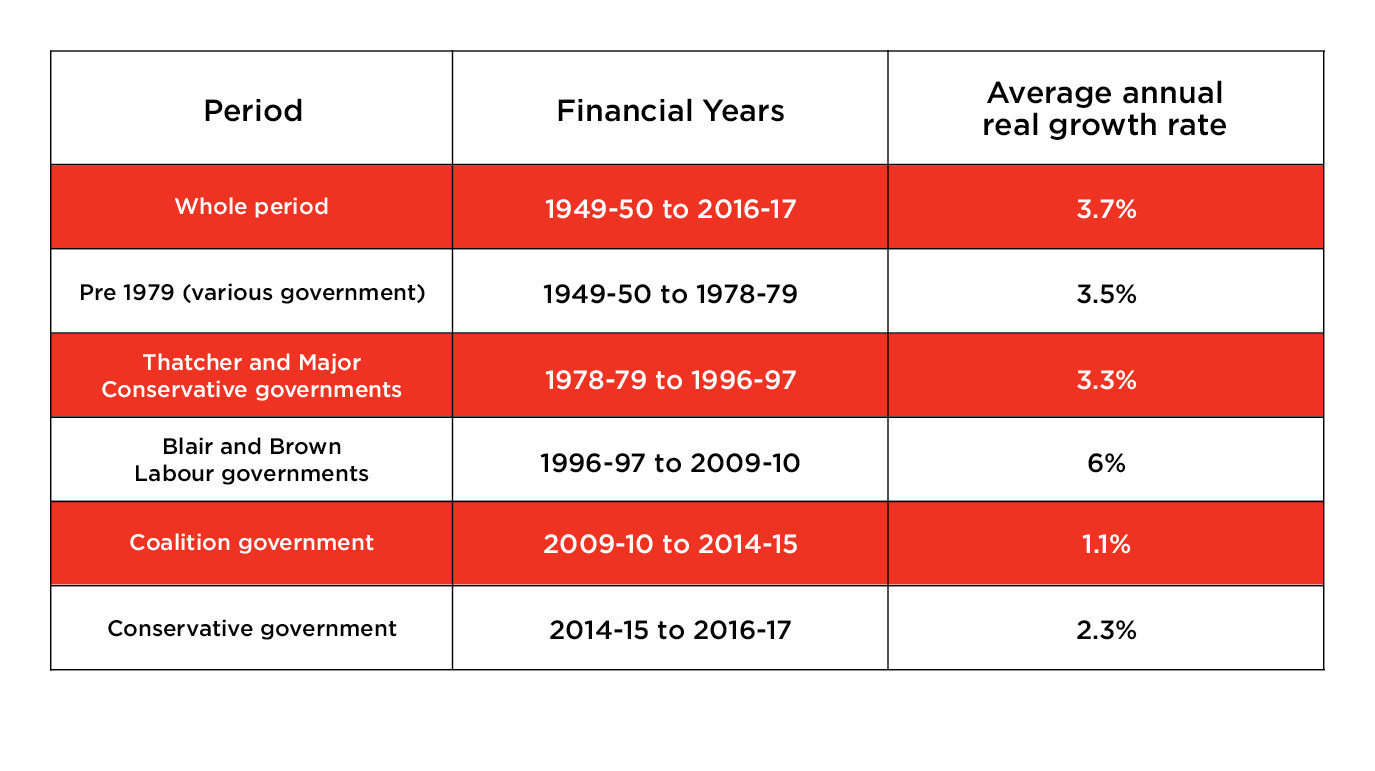

The “Brexit dividend” was yet another example of how party politics dominates a system that requires rational, clear thinking. Spending on the NHS has grown more slowly in the last eight years than in any comparable period since it was founded in 1948. The average annual growth rate was just 1.1%, in real terms, under the Tory-Lib Dem government from 2010 to 2015 – far less than the 6% in the Blair and Brown years.

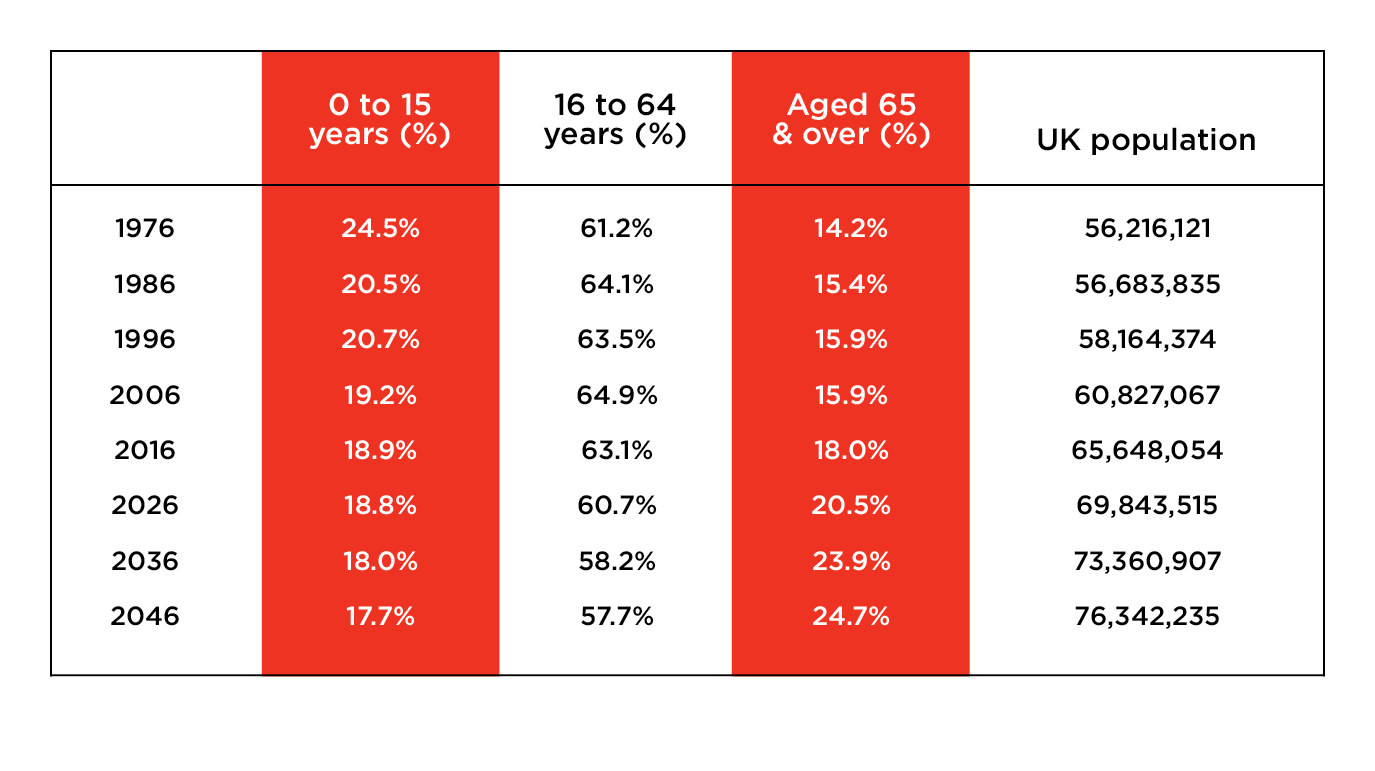

That doesn’t mean the health service has been ignored: In fact, the NHS has been more protected than other public services in the austerity years since 2010. But according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, it has “only just been enough” to care for an ageing population – particularly because spending on social care has fallen consistently over the same period.

NHS England chief executive Simon Stevens was reportedly arm-twisted into officially welcoming Hammond’s funding package, but he has been far from effusive. It “clearly represents a change of gear” and allows the NHS to make some medium-term decisions, he has said – hardly a ringing endorsement.

“Expectations will always exceed capacity. The service must always be changing, growing, and improving – it must always appear inadequate” Nye Bevan, 1948

On 5 July 1948, a 13-year-old girl called Sylvia Beckingham became the first person to be treated on the NHS when she was admitted to Park Hospital in Manchester with a liver condition. Visiting her that day was Aneurin (Nye) Bevan, Labour's health minister under Clement Attlee, whose vision of free healthcare for all was finally being realised.

The birth of the NHS followed a landmark report six years earlier from economist William Beveridge, who had proposed big reforms to social welfare to combat the five “giant evils” of society: disease, ignorance, idleness, want, and squalor. Labour’s support for his proposals during the Second World War paved the way for its electoral victory in 1945.

Yet Bevan, a coal miner’s son from the Welsh Valleys, was not starry-eyed about the new system and recognised that it needed to continually evolve to meet the needs of a changing population. Seventy years on, Stevens would quote his words at a health conference in London: The NHS “must always appear inadequate”.

Stevens said the health service must now look at what is working well and then “accelerate and universalise that”. That is a sentiment that would be welcomed by the users of the Aldershot café who, frankly, believe their service is an anomaly.

“I’ve got family in Scunthorpe and there’s nothing for mental health apart from the community mental health team, and it’s frustrating because I think, Why don’t we have one in every town?” Kirsty Wray says. “Because it’s not rocket science.”

The Safe Haven café is based in northeast Hampshire, one of 50 areas in England (dubbed “vanguards”) where new health and care systems are being trialled under Stevens’ “five-year forward view” launched in 2014.

The NHS is working with two charities to make it work. Every shift, there are three staff on duty: a psychiatric nurse provided by the Surrey and Borders NHS Trust, plus staff from mental health charity Andover Mind and drug and alcohol charity Catalyst.

Ruth Webster, the wellbeing centre manager, says: “Nine times out of 10, the work we do here is based around a cup of tea and a chat. Psych liaison [in A&E] don’t have time for that, and why would you want to wait for six hours for it?”

But the café is still equipped with everything that’s provided by the psychiatric team in A&E, with staff able to carry out a full mental health assessment and even section people if necessary.

The service was set up following a series of consultations with local people. An NHS source says: “A&E isn’t right for someone with a mental health crisis; a police cell definitely isn’t right. So someone thought, Hang on, shall we ask the people who are experiencing mental health crises what they need and what they want?”

And Webster says it’s having an impact on local emergency departments: While mental health attendances in A&E are rising across the country, they have stayed static in this area. That has a knock-on effect on the beds available in hospital, freeing up space for the people who need them most.

Crucially, NHS bosses are looking to the café as an example of how the health service can work with outside agencies to deliver care, particularly when it comes to mental health.

“We have social workers at Andover Mind, people who work in housing, drugs, and alcohol – that’s what you get with using the voluntary sector,” Webster says. “It’s not always a health problem, a lot of it is circumstantial.”

But the public reverence towards the NHS means there is an underlying resistance to substantial changes, and a nervousness among politicians to speak of the need for major reform. Andrew Dilnot said ministers needed to trust people more.

“I’ve been watching this space for 35 years and throughout that time I think there's been very little political debate that is serious in this area,” he said. “I can remember making a radio programme about this in the late 1990s just as the Conservative government was coming to a close and when it was becoming pretty clear that there would be a Labour government.

“I was interviewing both the secretary of state for health and the shadow secretary of state for health. And when the microphone was turned on, they both said they were sure the NHS could carry on and make efficiency gains. And when it was turned off, they both said, ‘Well, it’s absolutely clear that you’ve either got to have a lot more money in the NHS or it can’t carry on in the way that it is now.’

“But the political cost for either of them to say that in public would have been great. So the public political debate is frankly...well, it’s not very enlightening.

“I don’t believe it's impossible to have a mature public debate, but I do also understand the anxiety of politicians that whoever was the first – let's be honest about it – there's just a risk that the opposition to them would see that as an opportunity to say, ‘Party X wants to abandon the founding principles of the NHS – how could they be so callous?’”

In fact, anyone looking for serious answers to the most pressing problems facing the health service should probably avoid the House of Commons chamber altogether. Prime Minister’s Questions too often descends into a shouting match over health statistics that is baffling to viewers, inevitably culminating in Theresa May pointing to Labour’s record in devolved Wales.

Sarah Wollaston said she often had a “head-in-hands moment” at PMQs. “A lot of the debates on the NHS are so hollow and they’re just shouty and they don’t reflect the experience on the ground and what really matters,” she said.

It’s no wonder she and almost 100 backbenchers – including other select committee chairs and former ministers – have called for a cross-party commission to deal calmly and thoroughly with the challenges facing the NHS. Simply pledging more money, they say, isn’t enough; decisions need to be made on how that money should be raised and how it should be spent.

But Hunt said he sees no need for such a body. “I don’t think we need a cross-party commission now because we’re going to have a 10-year plan for the NHS with a five-year funding settlement.

“So I think the purpose of the cross-party commission was to help create a consensus on what that settlement should be, but Theresa May has taken a very brave decision to decide that herself and announce it and ... it means we get an answer this year rather than wait a long time.”

Wollaston said Hunt was wrong. “The commission is still necessary because we have to build a cross-party consensus on the difficult funding decisions about who and how we will pay, not only for the announcements on NHS England but to fund social care.

“So far the government have not set out how we will fund essential uplifts for social care, public health, workforce training budgets, or the capital for the backlog of repairs and new buildings. It is essential to level with the public about the scale of the funding needed if we are going to maintain – let alone improve – services, and to reach a consensus about how to raise this funding.”

She added: “There’s been political failure repeatedly on this and we can’t afford to have political failure.”

“There is nothing that destroys the family budget of the professional worker more than heavy hospital bills and doctors’ bills” Nye Bevan, 1948

Shadow health secretary Jon Ashworth struck a different tone, saying there has “always been politics around the NHS” and he would make no apology for holding the Conservatives to account over cuts to local services.

“I’ll always work with politicians to improve the NHS, but at the end of the day, it’s the Tories who’ve refused to give the NHS any funding. They’ve pushed it to the brink with eight years of austerity,” he said.

“Now they’re prepared to increase tax but it does beg the question: Why have they left it so late? Because it’s not a Brexit dividend, it’s going to be tax. They could have done this last year or earlier. It’s a PR exercise.”

Andy Burnham knows exactly what it’s like trying to drive through controversial policies in the bear pit of Westminster. The former Labour health secretary was determined to reform social care when he was in office from 2009 to 2010.

But private cross-party talks broke down, prompting the Conservatives to produce a doom-laden poster claiming that Labour wanted to introduce a £20,000 “death tax”, complete with “RIP off” inscribed on a headstone.

Burnham, now mayor of Greater Manchester, was furious. “I had exchanges in the lobby that night with [shadow health secretary] Andrew Lansley,” he said. “Looking back at it, that’s the worst of Westminster. The pettiness and the desire to put point-scoring first has actually stood in the way of a proper solution – and that’s a decade ago now, a decade of substandard social care.

“Looking at it from my new vantage point, I can see more clearly why the public get so frustrated with the way parliament and the political parties approach these issues. It’s fine to have differences and debate them, but with social care it’s a big failure of the political parties in my view.”

Social care for disabled and elderly people can range from some help with washing, cooking, and dressing to a full-time place in a care home. Unlike the NHS, it is not free and costs can rack up fast. Local councils are in charge and provide funding only for those who have the least money.

At the moment, that means people in England with savings of more than £23,250 have to fund it all themselves. (If they’re moving into a care home, that amount could include the value of their own home.) It is estimated that 1 in 10 people face “catastrophic” care costs – of over £100,000 – and it is impossible to buy insurance to protect against this.

Burnham had proposed that a compulsory charge should be taken from a person’s estate after their death. He still believes such a “care tax” – or “death tax”, according to his critics – is the only way to make sure the NHS and social care “speak the same language”.

“It’s only when you fund them on the same basis, so everyone contributes but everyone is covered, that you can begin integration proper,” he said. “As long as they are running to different sets of rules, you will always just be patching them together without them really integrating.

“Cancer is in the NHS; dementia may as well be in the American healthcare system because you are not protected, you are liable for a lot of cost, and why do we accept that?”

The next prime minister David Cameron instead pledged a lifetime cap of £72,000 on care costs for the over-65s from 2020, following recommendations from Dilnot’s review.

As Dilnot explained to BuzzFeed News: “So the better-off would still have to pay for the first X tens of thousands of their care but would know that if they’re one of the relatively small number of unlucky people with really high costs, they would be covered – and that would take away what I think is the last really big fear that people face.”

But May had other ideas and – out of the blue – unveiled yet another plan in her general election campaign last year. Cameron’s cap was dropped and instead the £23,250 threshold was raised to £100,000, so that people were able to pass this money on to their descendants.

May claimed it would be a fairer system because it would be paid for by taking away wealthy pensioners’ benefits, rather than through general taxation. But critics dubbed it a “dementia tax” because potential care costs for people with Alzheimer’s could be astronomical without a cap.

She was unprepared for the backlash and, despite her protestation that “nothing has changed” and her hasty pledge four days later that actually she would introduce an “absolute limit” on total care costs, the plan was dropped by her minority government last December.

Wollaston said it was “badly presented and badly timed”: “You can’t in the middle of an election campaign bring this in. A lot of people didn’t realise you already have to pay for social care. So it was portrayed as being a dementia tax but we already have a dementia tax – it’s just that it falls on 1 in 10 people over 65 with catastrophic care costs. … But it doesn’t get away from the fact that we do need to do something.”

Burnham agreed: “People are paying for social care now. They are actually paying huge amounts of money for their care – it eats through everything they’ve worked for – and actually the starting point should be not paying a tax but paying differently.”

Now the issue has been booted into the long grass once again, with a green paper due to be unveiled in November, alongside a blueprint for the future of the NHS. Yet the biggest demand on the NHS is from an increasingly elderly population who require both healthcare and help with daily activities. Wollaston said it was a mistake not to look at the two issues in combination.

“Yes, it’s great to rename it the Department of Health and Social Care but what I don’t think we should have is a green paper on social care in one place and a health service review in another place – they have to be dovetailed,” she said.

“Personally I would have liked to see one overarching review. They need to be working very, very closely together because what happens in social care has an impact on health, and public health affects them all.”

Hunt claimed it was not possible to set out spending plans for social care and public health at this point. “We decided we wanted to do something extra for the NHS frontline ahead of the 70th anniversary on 5 July,” he said. “And we also decided that the best thing was to give the NHS a really detailed plan, so we needed to announce the money we were prepared to put on the table ahead of the Budget.

“So we made an exception for the NHS, which is a pretty big exception to make, but we can’t make it for all Department of Health spending or local government spending as well because government has to stick to its rules about when these changes to government budgets are made.”

But he insisted: “It’s not possible to have a good NHS unless you have a real focus on public health and social care as well. … We have to do these things in stages to get them absolutely right.”

Dilnot said it had now “become impossible” to think separately about the NHS and social care.

“I don’t think there is the political will, probably not even the need, to make social care free for everybody but I think there absolutely is a need to take away the fear of catastrophe for people, which is why I’ve argued for introducing a new form of social insurance which is extending the provisions at the moment to include a cap,” he said.

"Even 20 years ago, social care affected a sufficiently small section of the population that you could think of it separately. Now the numbers have just changed.”

He pointed out that while there has been much innovation in the health market, with private companies creating new technologies aimed at speeding up diagnoses and treatments – such as the tech firm Babylon and its online GP app – the social care market is falling behind.

“The thing that is most odd about being a consumer of social care is that it's a bit like being in a shop with no prices,” Dilnot said. “Although you know how much it’s going to cost for you or your mother, father, grandfather in a residential care home or have domiciliary care each week, you have no idea how long it will go on for.

“So you don’t know what the price is – and in a context of where people don’t know what their final liability will be, it makes them very, very timid consumers, and where you’ve got timid consumers there’s very little incentive to enter the market and innovate because you can’t make any money. So our care market just doesn’t work well at all and that’s very distressing.”

Burnham said it was a huge mistake not to jointly fund the NHS and social care: “This desire to put NHS funding on a higher pedestal than everything else is a big problem.”

“It’s really frustrating,” he added. “I found it in my own party and again in 2015, the lack of courage on the topic is sad really. We’re all celebrating the birth of the NHS – well, it was courage that created it, it was a clear political vision and the will to stand up and argue for it. It just feels to me that modern politics doesn’t have the wherewithal any more to do anything on that scale.”

Paul Burstow, a former Liberal Democrat health minister between 2010 and 2012 who now chairs the London-based Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, said he was also frustrated with the lack of political will to reform social care.

“Something that disappointed me around my brief around social care was the Treasury attitudes to dealing with issues of future funding of care,” he told us. “It's always been a can to be kicked down the road – ‘Why sort this out today when we can leave it until tomorrow?’

“And I think the problem for the current government is that really the road is running out. There’s a growing recognition that social care is in a bit of mess, financially it’s incredibly fragile, we have large numbers of care businesses insolvent – and yet the Treasury seems to think that there’s nothing to be sorted out.

“That has a political risk to it that I don’t think has been factored in by the politicians. That was my biggest disappointment – that the Treasury was always a dead hand in all this.”

“We have accumulated in our passage through history, like an old ship on a long voyage, a considerable accretion of barnacles. It is our purpose to try to cut out the barnacles without mutilating the traditions” Nye Bevan, 1946

Major upgrades in public health and prevention have long been seen as the key to transforming the NHS. Yet these were conspicuously left out of the 70th-anniversary gift.

Just like social care, experts don’t believe public health can be considered on its own. Most funding for promoting healthy lifestyles and preventing diseases in England is handed to councils through a government grant – but this has been cut by more than 5% over the last five years, according to the King’s Fund think tank, with spending slashed on sexual health clinics and anti-smoking, drug, and alcohol services.

Ashworth said that with decisions on public health spending delayed until next year’s spending review, these services won’t get extra cash until 2020. “I think that’s nothing short of criminal and actually is not a long-term plan at all,” he said. “It’s more like a wing and a prayer.”

Meanwhile, the UK has one of the highest rates of obesity in the Western world: In 1980 just 36% of people aged 15 and over were overweight – by 2015, this had risen to 63%. Obesity quadrupled over the same period, with more than 1 in 4 people classed as obese in 2015. The related conditions of diabetes, coronary heart disease, and strokes are having a major impact on the NHS.

Stevens said last month that obesity was one of “two new epidemics striking our children” – the other being mental health problems – and that “we need to collectively mobilise”. Last month the government unveiled its plan to halve child obesity by 2030 – by stopping junk food being advertised on TV before 9pm and banning the sale of energy drinks to children, among other measures.

But whether this is the “radical upgrade in prevention and public health” that NHS England was calling for back in 2014 remains to be seen.

Wollaston is among those MPs and health experts who want to see the government taking public health more seriously. “If you’re living in a socially deprived community, not only is your life expectancy less but you’re going to be living more years in poor health, and it’s not right that that gap is getting wider,” she said.

“So what we need is a whole-system approach that looks at public health, social care … that’s what the prime minister said she’d do on the steps of Downing Street, she talked about burning injustices. Well, burning injustices for me isn’t just about life expectancy, it’s about healthy life expectancy and we need to do more about that.”

Burstow said bluntly: “If the 70th birthday present to the NHS doesn’t include some significant investment in upgrading prevention then we are on a treadmill of ever-rising demand that will be very hard to meet.”

He believes Britain's healthcare system is not currently fit “for the purpose of 21st-century living and 21st-century needs”, and warns that “some of the sacred cows of the 1940s NHS settlement have to be sacrificed to actually enable the money to be spent where it’s needed”.

This means a move away from “bricks and mortar” towards investment in new technologies to allow more treatment and care in the community. “If Bevan or Beveridge were to reappear today and looked at the fundamentals of the system, it would fundamentally be the one that they surveyed in the 1930s and 1940s,” he said.

“A system based on hospitals, dealing with infectious disease, dealing with consequences and curing, rather than addressing the 21st-century challenges that we actually have today.”

And addressing mental health problems at an early age is key, according to Burstow: “We know that half of lifelong mental health problems have their first signs in adolescence, so there’s a big prize to be had in reducing the numbers of people living with significant problems.”

Ashworth said the reality was that vulnerable young people are being forced to the other side of the country for psychiatric treatment because inpatient beds have been cut so dramatically. “Child mental health services budgets have been raided to fill the wider gap and I think we are in the midst of a mental health crisis for young people,” he said.

“Increasingly now, when I talk to staff on the frontline they are increasingly finding children admitted to A&Es with a mental health problem as well as a physical one.”

He praised charities like those in Aldershot working with the NHS to provide out-of-hours mental healthcare – but said the government needs to urgently boost funding across the country.

Back in the Safe Haven café, Danielle Hall, 27, is talking about her own experience with the community mental health team since hitting “crisis point” eight years ago.

“I’ve had times where I’ve handed in blades and they’ve taken them, no questions asked,” she says. “I’ve handed in medication when I was feeling suicidal. I just don’t know what I would have done without this place.”

She quietly reveals she has finally been accepted for psychotherapy treatment, after years of being refused because she was not deemed to be stable enough. “I only heard last week that I've been accepted after eight years of waiting,” she says with a smile. “I’ve been waiting so long to get this therapy and I know it’s what I need.”