The journalists at BuzzFeed News are proud to bring you trustworthy and relevant reporting about the coronavirus. To help keep this news free, become a member and sign up for our newsletter, Outbreak Today.

UK health secretary Matt Hancock took many people by surprise last week when he announced a new goal of 100,000 coronavirus tests a day by the end of April. It came after weeks of pressure on the government to come up with a serious plan on testing, after the World Health Organisation told countries to “test, test, test” for the virus.

The UK’s daily testing rate only just passed 16,000 on Thursday — far lower than Germany, which is able to test half a million people a week. NHS laboratory staff and testing manufacturers have poured cold water on Hancock’s ambitious target, warning of shortages of vital chemicals and test kits.

But other scientists and industry chiefs said the goal was achievable, thanks to three new “mega labs” being set up across the country — staffed by volunteer lab workers from the local area working 24 hours a day split across three shifts. This testing capacity will be boosted by extra labs run by businesses, research institutes and universities, to create the “biggest diagnostic lab network in British history”, according to ministers.

It’s no wonder, however, that many remain sceptical about the government’s new ambition given the mixed messages coming out of Downing Street.

Just three weeks ago, on March 19, prime minister Boris Johnson — who is now in hospital with the virus — said the UK was aiming for 250,000 tests a day. The next week, a senior figure at Public Health England said antibody tests — which check whether someone has had the virus and therefore could be immune — could be available within days on the high street. The government has since admitted that the 3.5 million antibody tests it has bought won’t be used because they’re not accurate enough.

BuzzFeed News takes a deeper look at how exactly the government is planning to carry out 100,000 tests for coronavirus every single day.

Why is testing so important anyway?

Testing for the virus is not a cure or a treatment. But it could provide the key to getting Britain out of lockdown and back on the road to normality. There are different tests that determine different things.

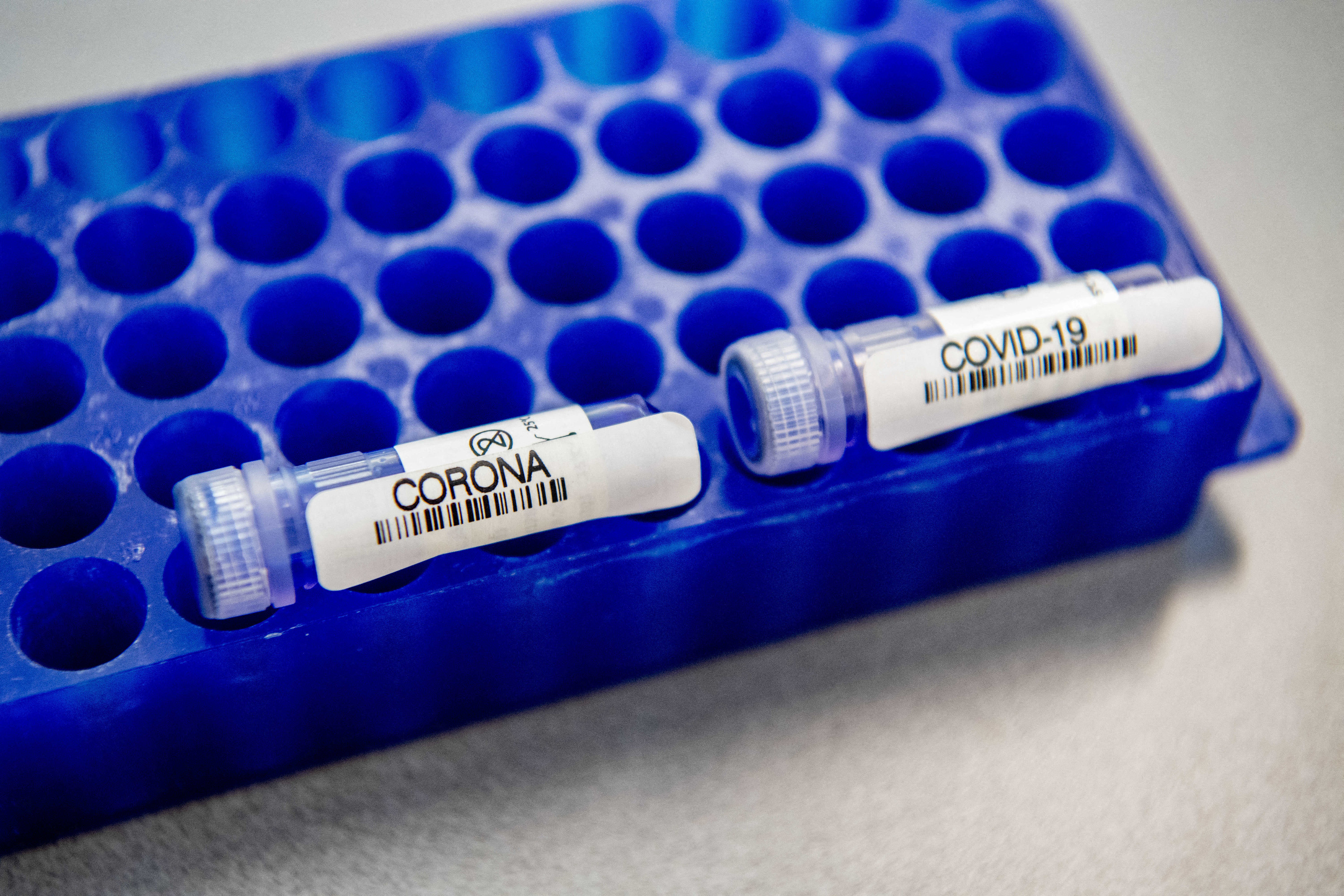

The one that’s being used at the moment is the diagnostic test which is being carried out in UK hospitals to see if somebody has COVID-19 right now. A swab is taken of the nose or throat and is sent off to a lab, with results back a few days later. These are also known as PCR (polymerise chain reaction) tests; they detect the genetic information of the virus.

At the moment, they are mainly carried out on patients who are being hospitalised for breathing problems. It means that medics can make sure they are getting the right treatment. “To take care of somebody you need to know if they’ve got the infection or not,” Sanjeev Krishna, a professor of molecular parasitology and medicine at St George’s, University of London, told BuzzFeed News.

When the coronavirus first hit the UK, people with symptoms in the community were tested too in a bid to isolate cases, track their contacts, and suppress the outbreak. But as the number of cases soared, the NHS did not have enough capacity to do this and those with key symptoms — a dry cough and/or high temperature — were told to self-isolate for seven days instead.

Yet ultimately it is important to test as many people in the community as possible, even if many of those with suspected coronavirus are staying at home. That’s because many people are believed to have the virus without displaying any symptoms at all. If you can pinpoint these people and keep them at home, you can further slow the spread of the virus.

A key priority now is also testing NHS workers and their families who are currently in isolation because someone in the household is showing symptoms. This is to make sure that those who test negative, or with family members who test negative, can return to work. As of Thursday, there were 13 drive-through sites for NHS frontline staff and their families in operation across the UK, helping to provide labs with patient samples. The government has pledged to roll tests out to other key workers, including care workers and prison officers, as soon as possible.

Will there be another test that shows we have already had the virus?

This is called the antibody test; it works by using a pinprick of blood to check whether people have had coronavirus and therefore could have immunity. Once proven in a lab setting, this could potentially be done at home, with the results available in just 20 minutes.

Antibody tests matter because when carried out on a mass scale, they could inform when social distancing measures can be lifted.

The UK government bought 3.5 million of these home testing kits — but after testing them, have deemed them too inaccurate to use safely. Kathy Hall, director of COVID-19 testing strategy at the Department of Health, told the House of Commons science committee on Wednesday that the government was now “working with the companies to cancel the orders and get our money back where possible”.

Yet only two weeks ago, Sharon Peacock, the director of the national infection service at Public Health England, had raised hopes that the kits would be available on the high street and on Amazon within days. The government’s own testing strategy, published last weekend, says antibody testing kits are “some way off”.

Ministers are now keen to develop a homegrown antibody test in the UK, by offering grants and other support to organisations. They have launched the UK Rapid Test Consortium, which comprises Oxford University and diagnostic companies Abingdon Health, Omega Diagnostics, BBI Solutions, and CIGA Healthcare, to develop a reliable antibody test as quickly as possible.

Professor Sanjeev Krishna, who is also working on an antibody test with the company Mologic, said: “You can only really make decisions on how to manage this pandemic once you’ve got some figures in place on who’s had it, who’s in the process of having it and who is at risk of getting it. And if you need to make very targeted interventions to reduce upsurge in the NHS, to let society get back into some sort of regular routine, you’re going to have to rely on good testing.”

Antibody tests are already being used as part of a research programme operated by Public Health England at Porton Down, the government’s high-security lab campus in Wiltshire. They are testing blood samples of the population — 800 so far — to better understand the rate of infection and how the virus is spreading across the country. But the goal is to be able to do this on a mass scale.

So will the antibody test contribute to the 100,000-a-day target?

Hancock wasn’t clear on this. But John Newton from Public Health England, who is overseeing the government’s plan on testing, said it was highly unlikely that antibody tests would be part of that goal.

“We do not expect to be doing antibody tests by the end of April,” Newton told MPs on the science committee. “We’re not relying on antibody tests to make up that target.”

Allan Wilson, president of the Institute of Biomedical Sciences, which represents NHS lab workers, agreed. “I don’t think any of these will be antibody tests,” he told BuzzFeed News. “Matt Hancock was vague about the mix of the virus test and antibody test but now everyone is pouring cold water on the antibody test because it’s not accurate. I think [the target] will entirely be about testing for the virus on laboratory platforms.”

In that case, how on earth can the government increase the number of tests so fast?

This is the million-dollar question. Hancock has insisted it can be done — but only with the help of universities, research institutes, and major pharmaceutical companies to boost testing capacity. Sir Paul Nurse, director of the Francis Crick Institute in London which has been turned into a testing lab, admitted this week “it will be a stretch”.

Allan Wilson was blunter. “I frankly don’t think we will meet that 100,000 figure,” he said. “I think it’s very challenging. I think Hancock was pushed for a number after this mantra ‘test, test, test’ and he almost just plucked a figure out of the air that sounds impressive. It was a political soundbite just to take the heat out of it.”

Wilson also criticised Hancock for failing to talk to NHS scientists and lab staff before announcing the figure on air: “You’d think it would be nice to speak to the people who would be delivering that number before he went public with it.”

NHS leaders have warned about severe shortages of the key chemicals and swabs needed for the diagnostic test, amid intense global competition for the same components. This includes the “lysis buffer” that allows labs to break open the virus from a sample so they can test it. Scientists are finding innovative ways around these shortages and things are slowly improving, but not fast enough according to some.

Wilson said: “Every country is fishing from the same pond. We're not at the front of that queue because we don’t have much of a diagnostic industry in the UK, certainly not one that can produce the kits for the high capacity platforms. And we were late to market because the UK government decided to try other things before they decided ‘Oh we better do some testing’ and by that time, a lot of the companies had already committed their resources in the supply chain to other countries.”

So what are these “mega labs” and will they be able to do this many tests in just a few weeks?

Three new labs are being set up by the government in Milton Keynes, Glasgow, and Alderley Park, Cheshire; each will have the capacity to test tens of thousands of patient samples each day.

The lab in Milton Keynes is already fully operational, with 150 workers testing thousands of swabs every day, and automation robots being put in place to increase capacity even further. The other two labs will be operational in the next two weeks — but this leaves little time to meet the 100,000-a-day target.

Dubbed the “Lighthouse Labs”, they take their name from the PCR testing technology which uses fluorescent light to detect the virus.

They are being “actively supported” by pharma firms GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and AstraZeneca, who are providing “access to data and resources”. These companies are also exploring the use of alternative chemical reagents for test kits in order to help overcome supply shortages.

But they won’t be staffed by NHS lab staff. The workers are volunteer lab technicians from the local areas, all of whom have significant experience working in a similar facility, according to government sources. They will all be trained to make sure they keep to required standards and will be working 24 hours a day, split across three shifts.

Allan Wilson, who represents NHS lab workers, said: “One of our main frustrations, apart from the supply chain, is we can help these [mega] labs, we can work together. We’d be keen to work with them, but they seem determined to work without the expertise that exists within the NHS labs.

“This is bread and butter to us, biomedical scientists in NHS labs up and down the UK, we do high-quality testing, that’s what we do. And yet we’re being excluded from helping in setting these labs up, and Public Health England (PHE) among others seem determined to do this themselves.”

Government sources insisted that the NHS had been “involved every step of the way” and the intention was to make sure NHS lab workers were not moved from the important work they were already doing.

A Department for Health and Social Care spokesperson said: “Each of our Lighthouse Labs will be staffed by a team of highly skilled and experienced lab technicians drawn from the local area. We are absolutely delighted that these people are playing a vital role in tackling this virus and saving lives. We are extremely grateful to each and every single one of them.”

Will there be other new testing facilities too?

The UK government has launched a call to arms for private laboratories and institutions to offer up their facilities and crucial testing components.

Cambridge University is working with AstraZeneca and GSK on a new facility that aims to process 30,000 tests per day — although this is not expected to be “fully up and running” until the beginning of May.

The Francis Crick Institute has also been transformed into a major testing facility, in partnership with University College London Hospitals, with 50 scientists currently working on coronavirus testing, primarily for NHS staff.

And US firm Thermo Fisher has said it will supply the UK with testing kits and is working to scale up manufacturing at its UK sites. The company’s chief operating officer Mark Stevenson told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme on Thursday: “We agreed with the UK that we would supply to meet their demand of more than 100,000 tests per day.”

But Tory MP Greg Clark, who chairs the Commons science committee, warned it was all happening a bit late. He said after his evidence session on Wednesday: "It was heartening to hear of the Dunkirk spirit being adopted by research institutes and companies, who are playing their part in ramping up the UK’s testing capacity.

“However, it seems as though this call to arms should have been made earlier. The government must ensure that all parties are brought on board as early as possible to tackle future challenges in this crisis, such as antibody testing and vaccine development and manufacture.”

We do seem to be behind the curve on testing — why is that?

The UK government has faced constant questions over why it has failed to carry out coronavirus testing on the same scale as other countries, particularly Germany which has seen a high testing rate and a lower death rate.

England’s chief medical officer Chris Whitty admitted on Tuesday in a press conference: “We all know that Germany got ahead in terms of its ability to do testing for the virus, and there’s a lot to learn from that.”

This was a long way away from the government line on testing just a few days earlier. An internal memo sent to ministers and MPs last Wednesday told them what to say if they were asked why the UK was not following World Health Organisation (WHO) advice to "test test test" like Germany.

"When the WHO talks about testing, it is addressing the global system. Not all countries have the same infrastructure as the UK and there are countries that the WHO needs to press on testing," it said.

This was replaced with a new line to take on Thursday that was almost the complete reverse. "Increasing testing capacity is the government's top priority, and we are working around the clock and across the country to rapidly boost capacity," it said.

BuzzFeed News has reported on why the UK has been testing fewer coronavirus cases than even the US. Health experts said this stemmed from Britain’s controversial initial strategy of mitigation of the virus (rather than suppression), rendering testing a secondary concern.

Government scientists took the view that the UK should not attempt to suppress the outbreak entirely, but rather prioritise protecting the elderly and vulnerable and ensure the NHS did not become overwhelmed, while allowing the rest of population to build up “herd immunity”.

This strategy meant that widespread testing of every coronavirus case was not a priority for the UK, the person said, since the scientists were assuming that between 60% and 80% of the population would become infected.

Accordingly, no preparations were made to increase manufacturing or imports of testing kits, nor to expand the UK’s laboratory capacity.

Hancock’s pledge of 100,000 tests a day last Thursday came after repeated pressure on ministers at the daily press conferences to explain the testing strategy. After weeks of being accused of overpromising and underdelivering, the government now needs to make sure it can stick to this target.