We hate robots.

And then we love them.

And then we hate them again.

Our love/hate relationship with robots isn’t exactly new. But it has never been more real than it is in automated interfaces today.

Increasingly, machines move with action that seems genuinely spontaneous. We don’t always admit it, but we consider these robots alive. We call automatic assembly systems "robot arms." We refer to the automated programs in the background of unix systems as "daemons." We chat with Siri and yell at our GPS. A poorly programmed robot is clumsy, but a poorly designed door is broken.

At the same time, we can dismantle, debug, and replace robots. Robots exist, then, in a half-alive state. The concept of a not-living and not-dead object should be hard for our brains to handle, except that we’ve been seeing such objects in movies for years.

In movies, toys, robots, and other unreal creatures come to life. They can be attractive, repulsive, alluring, or dangerous, and unambiguously alive.

Hollywood knows that a viewer’s love or hatred hinges on common emotional cues. Designers take advantage of baby-like big eyes and rounded shapes to make us love creatures:

Add signal colors for danger, sharp edges or glowing eyes to make a creature seem sinister and predatory:

Giving too many human attributes to a robot will make it seem creepy:

But an autonomous robot is less creepy if it looks less human:

Automated interfaces struggle with this same half-alive state, and their designers play with the same emotional cues we know from the movies. Sharp edges and eerie red signal lights tell us to stay away. Soft, rounded textures and soothing cues, on the other hand, can make us love an automated interface.

Machines that look too much like animals or talk too much like humans are inherently creepy. They fall into the uncanny valley, and frighten users. Giving an interface lifelike attributes and balancing it with nonthreatening mechanical exteriors can solve this problem, keeping users attached, instead of disturbed.

As a designer, I am drawn to the challenge of finding the right balance between not-lifelike-enough and too lifelike. Emotive, lifelike design is essential for automated interfaces. I love looking for new ways to establish emotional attachment in the single second it takes a consumer to make a decision.

Designs that mix “lovable” cues with “scary” cues cause users to flip-flop emotionally. When product design leaves a user flip-flopping, their experience is ruined. Most users know when a product strikes the wrong chord, but far fewer can tell you why.

To experiment with mixed emotional cues, I built the Starfish Cat and named him Burbles.

Burbles the Starfish Cat is an exercise in exaggerated ambiguity and discomfort. He has an adorable kitten upper body, but a flat, rubbery starfish base. He has gently closed eyes and a contented purr, but raking white claws and a high pitched cry. Without warning or permission, he meows pathetically and rakes his claws in the direction of human body heat. If someone decides to hold him, he purrs gently. Most people enjoy this, until he tries to suckle them with the unexpected mouth in the center of his rubber base.

And as expected, people hate it.

And love it.

Then they hate it again.

Starfish Cat is a carefully calibrated mishmash of emotional cues. He has five IR temperature sensors, five servos, a flexible 3D-printed skeleton, a speaker, and a pneumatic motor.

I chose each motion and sound to switch the brain constantly between repulsion and attachment.

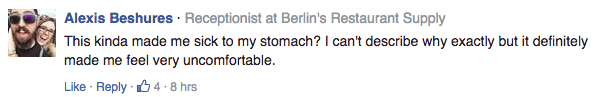

When they have a chance to hold it, most people are comically uncertain about Burbles the Starfish Cat. Many watch me while they hold it, waiting for me to tell them how they should react. Online comments suggest that readers feel the same way.

Good emotive design is essential in an age of automated interfaces. Design responsibly, with emotion in mind. It’s the difference between love, and this:

Now that I’m done with Starfish Cat, I think I owe it to the world to make something unambiguous. Either something adorable that sparks instant love, or something horrible, repulsive, and alien. The in-between unnerves everyone it touches, and I’m no exception.

Starfish Cat is open source! If you’d like to build emotional triggers into your own projects, check out the github repo.

The Open Lab for Journalism, Technology, and the Arts is a workshop in BuzzFeed’s San Francisco bureau. We offer fellowships to artists and programmers and storytellers to spend a year making new work in a collaborative environment. Read more about the lab, read more from Christine, or check out Christine's website.