My depression is constant but mutable: here a sustained melancholy, there a waking anxiety, now a sharp pang of doubt. In recent years, it has manifested as a recurring suspicion — quiet at first, but eventually needling its way into the forefront of my mind — that the life I'm living is false. It spreads like a tear in the fabric of my reality, offering glimpses of what it insists is the truth beneath it, full of chaos, panic, and utter ineptitude. It's a secret that I'm finally in on, a higher level of understanding; I'm at once doomed and freed; the world is dark but at least my eyes are open in it; I'm just as bad as I feared. Then it passes.

This depression is mine; others' belong to them. Their lows, their coping mechanisms, their definitions of recovery, and their paths to or through it, would be as foreign to mine as any other ailment. And since the most visible stories of depression focus more on redemption — usually in the form of some strong will, a pill, that person who finally gets you — than on the struggle, the surest conviction held by the depressed person is the singularity of her experience of it. All of this to say I did not expect to find my own depression narrated back to me in a YA novel about two high-schoolers in love.

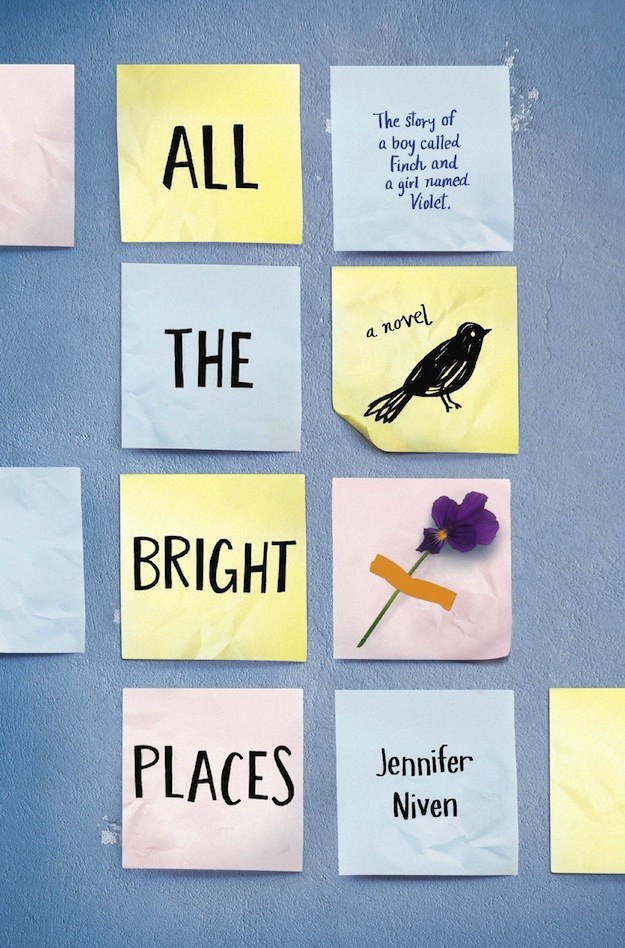

"Is today a good day to die?" wonders Theodore Finch in the very first line of All the Bright Places, Jennifer Niven's remarkable YA debut. The teenage outcast is standing on the ledge of his school's bell tower, weighing the pros and cons of ending it all. The scene doesn't feel especially dramatic or urgent; if anything, it's alarming in its mundanity. He considers the question evenhandedly until he spots Violet Markey — a popular girl still reeling from the death of her sister — who is apparently wondering the same thing.

The pair make it down together safely, if a little embarrassed, but quickly realize their connection lingers. What follows is a roller coaster ride of a romance, not without its flaws (Finch's behavior borders uncomfortably on stalking at times) but impressively layered, lived-in, and real. Violet is a strong and inspiring protagonist, relocating her passion after family tragedy sapped her dry, but it's Finch who continues to stick with me.

Though she never explicitly names it, Niven's portrayal of manic depression, and teenage depression in particular, is deliberate and unsanitized. Finch's first-person narration (which alternates with Violet's) is an authentic presentation of living in the thick of depression — not fighting it, not recovering from it, just living it — and it's best when it makes the reader uncomfortable. Finch pulls no punches when he jokes with his guidance counselor about who will be the first to know when he goes, and neither does Niven, as she forces us to confront the myriad reasons a human being, not a caricature of one, considers suicide.

We meet Finch on day six of being "awake," a condition that he defines by its opposite — the spells of days or weeks he describes as being "asleep" or "down" — and that he is desperate to maintain. He stockpiles days of clarity as if to fortify his happiness, but the "sleep" rears its head from time to time. Consider his narration on a particularly bad day:

At school, I catch myself staring out the window and I think: How long was I doing that? I look around to see if anybody noticed, half expecting them to be staring at me, but no one is looking. This happens in every period, even gym. In English, I open my book because the teacher is reading, and everyone else is reading along. Even though I hear the words, I forget them as soon as they're said. I hear fragments of things but nothing whole.

Niven manages to encapsulate not only the feeling of lost time, but also the simultaneous, contradictory feelings of alienation (I'm an outsider) and narcissistic paranoia (But everyone is looking at me!). It's the kind of thing that can inspire paralytic anxiety, or, at worst, a sense of claustrophobia, as when Finch explains the way the world around him just seems to shift: "I've… learned to look out for things like changes in space, as in the way you see it, the way it feels."

But Finch is also frustrated by the failure of language to effectively translate his reality. It's evident in his reliance on the insufficient sleeping-waking metaphor, but also in his desire to communicate the validity of his illness. "The fact is, I was sick, but not in an easily explained flu kind of way," he thinks. "It's my experience that people are a lot more sympathetic if they can see you hurting, and for the millionth time in my life I wish for measles or smallpox or some other recognizable disease just to make it simple for me and also for them. Anything would be better than the truth: I shut down again. I went blank." Such a cruel and tiresome task, to carry both the weight of depression and the burden of legitimizing it.

To cope with his depression, Finch plays with different identities, trying on and taking off personas like outfits. At first it's no more harmful than your run-of-the-mill eye roll-inducing quirk (wouldn't it be wacky if I spoke with a British accent for a few weeks?) but as the story progresses, it becomes more obviously symptomatic of manic episodes. Perhaps the most poignant aspect of Finch's struggle is here, in the way it bullies him into disorientation. "Which of my feelings are real?" Finch wonders, with heartbreaking earnestness. "Which of the mes is me?"

I was a sophomore in high school on the day I was most certain I would do it. I had been sad for a very long time, but I'd recently decided that I had no right to be so consumed by what I concluded was an unjustifiable, self-indulgent emotion. Mostly, I didn't really feel like being sad any longer. I remember going through the day and smiling at people I passed, neatly and resolutely closing chapters in my life. I remember trying to pay attention to each conversation, understanding the significance of what I assumed would be last encounters, but still unable to clearly hear anyone else's voice over the humming in my brain. I remember that it was snowing. I remember shades of gray.

At home that night, I stayed up later than the rest of my family, went to the medicine cabinet in the downstairs bathroom, and pulled out a bottle of ibuprofen. The recommended dosage was two pills; I knew for a fact that in the case of killer headaches I never took fewer than four. I grabbed a handful of pills, rolled them around in my fist. I put a few back in the bottle. I read the label again. I swallowed thirteen. I was desperate, dramatic, naive, and sad, and the worst thing I could bring myself to do was take a slightly-above-the-recommended dosage of a nonprescription pill.

Thankfully it didn't do much of anything beyond causing some mild and prolonged indigestion. I woke up the next morning relieved — embarrassed at the emotion I had indulged, grateful that my family suspected nothing other than an upset stomach, and, most surprisingly, feeling a touch invincible. I stayed home sick and watched Bobby Flay cooking shows on the couch with my mom.

I was absent a lot over the course of high school, missing upwards of a quarter of my senior year and graduating mostly on the goodwill garnered from my reputation as an overachiever. It would take starting college, promptly dropping out of college, and enrolling in an outpatient facility for eating disorders before my depression would be diagnosed and treated, but those in-between years were filled with countless periods of "falling asleep" and then grasping for any way to accurately explain them. And though I never attempted self-harm again, this ideation — the rumination on, and then dismissal of, suicide — became a sort of coping mechanism in its own right. What better way to remind myself I wanted to live, than considering all of the many things I would miss if I didn't?

This, to me, is the most striking and intimate of Niven's revelations. I've been galvanized by every moment in which I decided I'd like to live, and Finch — who keeps a daily list of the reasons he hasn't yet ended it — has the same epiphany when he walks away from the bell tower ledge. "I'm fighting to be here in this shitty, messed-up world," he thinks, assuming no one will believe him. "Standing on the ledge of the bell tower isn't about dying. It's about having control. It's about never going to sleep again."

Or, later, in a suicide support group: "I do it because it reminds me to be here, that I'm still here and I have a say in the matter." It's a false and arguably dangerous sense of invincibility, yes, but there is value in feeling accountable, even powerful, in your life. I've yet to define my own recovery, but perhaps it involves figuring out how to feel that power elsewhere.

To linger on the idea of recovery for just another moment: Niven's greatest honesty comes in her refusal to promise or prescribe it, never sparing us our fear for Finch's safety. There can be worthwhile mental illness narratives that aren't tidied up with bows; there is comfort in seeing an experience that feels so isolating lived out unapologetically on the page or screen. These stories are as tenuous and messy as living with depression can often be. What you learn — what I've learned — is that the notion of a singular wakeup call or turning point ends up to be misguided, even quaint.

The turning point becomes all of the many ways you'll claim your agency amid the chaos — the getting out of bed, the discovery of a new TV show, the 3-mile run, the text to a friend, the silly joke you make on Twitter that someone decides they like. Each is its own monumental feat, which you'll perform, and again, and again, if only to remind yourself you can. And if along the way, you find you aren't as alone in it as you believed? What a relief and gift that can be.

All the Bright Places (Knopf) is out now.