James Bond is irresistible to women. This is something we all know to be true.

And this is why, over the course of 1964’s Goldfinger, Sean Connery’s Bond has three sexual partners: Pussy Galore (Honor Blackman), a lesbian pilot who “succumbs” after he violently pins her to the ground in an isolated barn; Jill Masterson (Shirley Eaton), who is charmed by Bond’s prying questions about her sex life; and some woman in a tub (Nadja Regin), whom Bond uses as a human shield. In the 1969 movie On Her Majesty's Secret Service, where Bond (George Lazenby this time) meets and marries Tracy (Diana Rigg), he has sex with two other female characters for no real reason, and through the trysts, he reveals his identity to a would-be mass murderer. Roger Moore reached his 007 per-mission high with four sex partners in his last Bond film, 1985’s A View to a Kill.

But it all changed with GoldenEye a decade later. Or rather, it sort of changed with GoldenEye. Miss Moneypenny (Samantha Bond), longtime enthusiastic recipient and slinger of double entendres, tells Pierce Brosnan’s Bond quite early in the movie, “This sort of behavior could qualify as sexual harassment.” It’s a joke, and it’s funny, and she then one-ups his innuendo and the audience moves on. It was the birth of Ironic Bond.

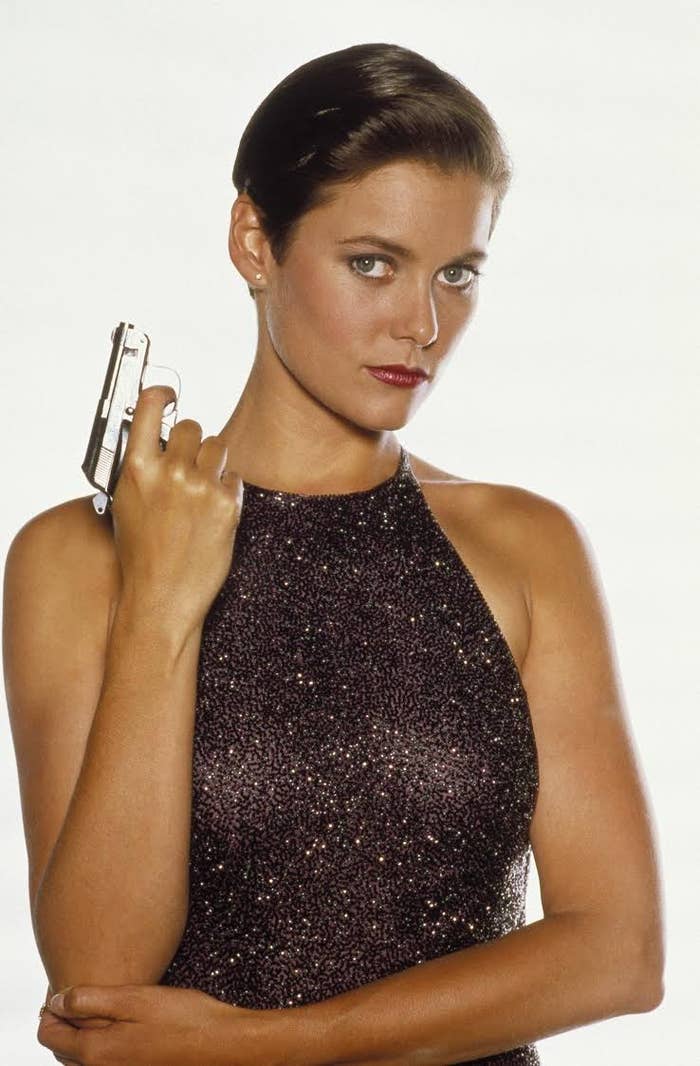

Ironic Bond has his roots in the two movies that precede Pierce Brosnan’s Bond residency: “What to do with the women” is a problem the films noticeably wrestled with starting with 1987’s The Living Daylights, the first with Timothy Dalton as Bond, which comes just after the preposterously sex-filled A View to a Kill. In The Living Daylights, Bond’s main “girl” is a cello virtuoso, and at the end of the film, he attends her cello performance, which has nothing to do with his mission, signaling to the audience that she is a human being with needs outside his own. Dalton’s second film has two main Bond girls, and one is a former Army pilot who yells at him when he tries to diminish her vital contribution to Bond’s continuing heartbeat (“If it wasn’t for me, your ass would’ve been nailed to the wall!” she rightfully shouts). It’s clear that this character, Pam Bouvier (Carey Lowell), is a “liberated woman.” In 1989, USA Today called her a “tough, brainy pilot — who still looks good in a bathing suit” and noted that “Bouvier, unlike previous ‘Bond girls,’ saves 007’s hide more than a few times.”

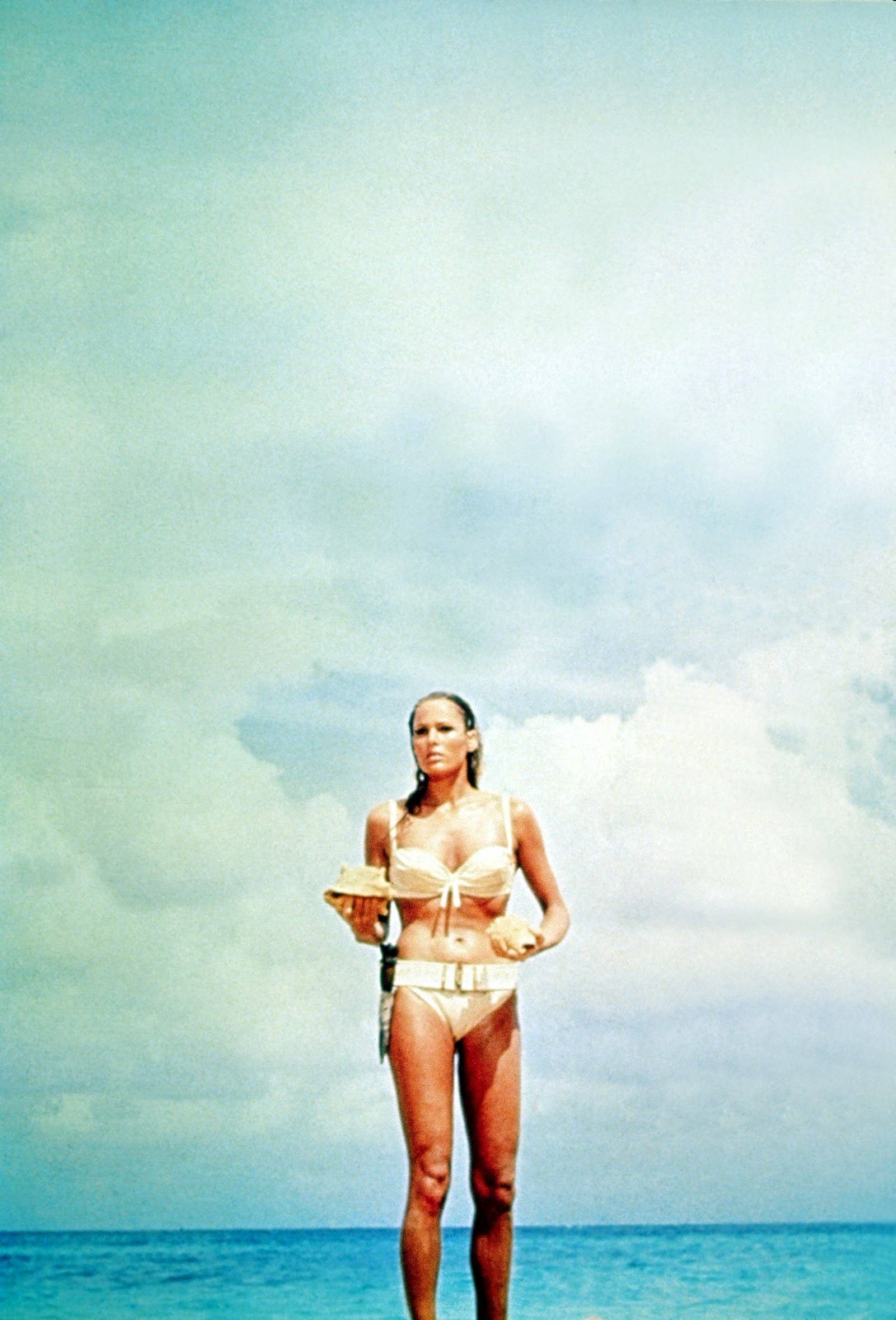

And the Different Bond Girl Assertion is still with us: Vanity Fair claimed that the latest Bond movie, Spectre, offers a “new take on the Bond woman,” and director Sam Mendes told the magazine, “[T]hey’ve lived lives before meeting Bond, and they’re not simply adjuncts.” It is both an undeserved compliment for his own film and an oversimplification of the 23 that precede it: The very first Bond girl, Honey Ryder (Ursula Andress), murdered her rapist before the action of the film starts, for example, and runs a successful shell-selling business. The improbably named Octopussy (Maud Adams) in the eponymous 1983 film is the feared and respected head of a women-only smuggling operation. Over the course of 24 films, Bond romances 16 spies, all of whom have had prior adventures much like Bond himself. Two of those lusty spies were also trained ballerinas.

The Vanity Fair interviewer doesn’t press Mendes on his claim though, much like the USA Today writer didn’t question how different Pam Bouvier was from her predecessors in 1989, despite the fact that at the time, Bond’s life had been saved by a woman in no less than nine previous movies.

Thus, you might not be surprised to learn that in fact, both women Bond sleeps with in Spectre yield to his sexual advances quickly and ludicrously: Lucia (Monica Bellucci) slaps him during an argument and then he shoves her against a mirror and they kiss, a moment that elicited laughter when I saw it in the theater; Dr. Swann (Léa Seydoux) saves Bond during a vicious fight with an assassin, and then asks, “What do we do now?” The film then cuts to a vigorous makeout, which also drew laughter. You might also be unfazed to learn that during the opening credits, a woman is seemingly penetrated by a stylized octopus in a moment that bears a not-insignificant resemblance to the clip a boy showed me in 2008 after I said to him, “What is hentai?”

Daniel Craig’s most recent Bond, like Pierce Brosnan’s Bond before him, is Ironic Bond. He leans into the absurdity of his sexual encounters, with a wink to take the edge off. By the time GoldenEye came out in 1995, that angry vagina in the room was gaping so widely that M, reimagined as a woman played by Judi Dench, had to acknowledge it: “I think you’re a sexist, misogynist dinosaur,” she tells Bond after he inexplicably is able to seduce a twitchy psychologist in a professional setting. “A relic of the Cold War, whose boyish charms, though wasted on me, obviously appealed to that young woman I sent out to evaluate you.” Previous male iterations of M had chastised him for letting his penis jeopardize his work, but this M, a woman, confronts his misogyny explicitly. And, by anticipating the audience’s critique, GoldenEye thinks it has solved the problem, and moves on.

The attitude has more or less stuck: In Casino Royale, Craig’s first Bond film in 2006, Vesper Lynd (Eva Green), in a monologue demonstrating that she is Bond’s intellectual equal, tells him, “You think of women as disposable pleasures rather than meaningful pursuits,” as if the acknowledgment that his behavior is wrong absolves the film of responsibility. Her criticism distances the audience and the filmmakers from Bond’s attitude, and it’s a false, inadequate distance that reveals itself in the word “pursuits” — women, of course, are meaningful and exist outside of being sexually pursued. Vesper’s critical monologue notwithstanding, Bond’s treatment of women continues, and the audience understands that his relationship with Vesper is different because, as he tells her, she’s different from other girls — a signal to any woman with sense to turn in the opposite direction and flee, hurling used sanitary napkins over her shoulder. Casino Royale, however, deems his gesture deeply romantic.

The lack of self-reflection does not extend to all unsavory aspects of the character — during Craig’s tenure, the franchise has deftly balanced “James Bond is a human being” with “James Bond is a cold-hearted murderer.” In Casino Royale, Craig sits fully clothed in a shower next to a shaken Vesper just after he’s killed a man in front of her. He puts his arm around her, and he gently sucks the sin off her fingers. This was the installment in the franchise where we had to collectively acknowledge the corrosive nature of Bond’s horrific job. Craig’s performance spotlights the character’s contradictions, eliciting our discomfort with his savagery. And yet, he insists on Bond’s troubled humanity.

But our discomfort with the female characters is not solved through an insistence on their humanity — it is solved with a shrug. Craig’s Casino Royale, Quantum of Solace, Skyfall and Spectre all make the audience cringe at the violence; there is no such equivalent compunction over his treatment of women. When his actions in Casino Royale lead to a woman’s death, M notes that he doesn’t get emotionally attached; when his actions in Quantum of Solace lead to a woman’s death, he is more angry at M for criticizing his tactics than anything else; when his actions in Skyfall lead to a woman’s death, he seems shaken but unrepentant.

When he kills a man in these past four films, we see the horror of Bond, but when a woman dies because of him, we see an unfortunate casualty — a sad accident in a vicious world, an error rather than an immoral act. The deaths of men show us something broken in Bond, while the deaths of women show us something broken in the world: No individual takes particular responsibility for women’s peril, not until Spectre, when the villain, a stand-in for the cruel world, claims responsibility, and thereby absolves Bond. Other characters consistently question the morality of Bond’s murders, but they only question the utility of his womanizing and its attendant risk. Killing is a wrong thing he chooses to do, but treating women as objects is at worst a character flaw. The murders in these films are by and large no longer glamorous, but seducing beautiful women in exotic locales and leaving them as soon as it suits him, that is still mysterious and appealing.

At least in Spectre, the women don’t die, which is what Mendes should have said: While the director believes it’s remarkable that “they’ve lived lives before meeting Bond,” what actually sets them apart is that they’ll live lives after meeting Bond. They are certainly only there to teach Bond something or to have orifices, thus, contrary to Mendes’ claim, they are certainly adjuncts, albeit adjuncts who talk back. But they always have, starting with Honey Ryder’s annoyance at Bond’s interference with her shell-harvesting. The difference is that we’re now uncomfortable enough with blatant contempt for women to disavow it, but not uncomfortable enough to actually change. You can call Spectre’s women “a new take” if you want to, but it’ll just seem like you weren’t listening to the other Bond girls.