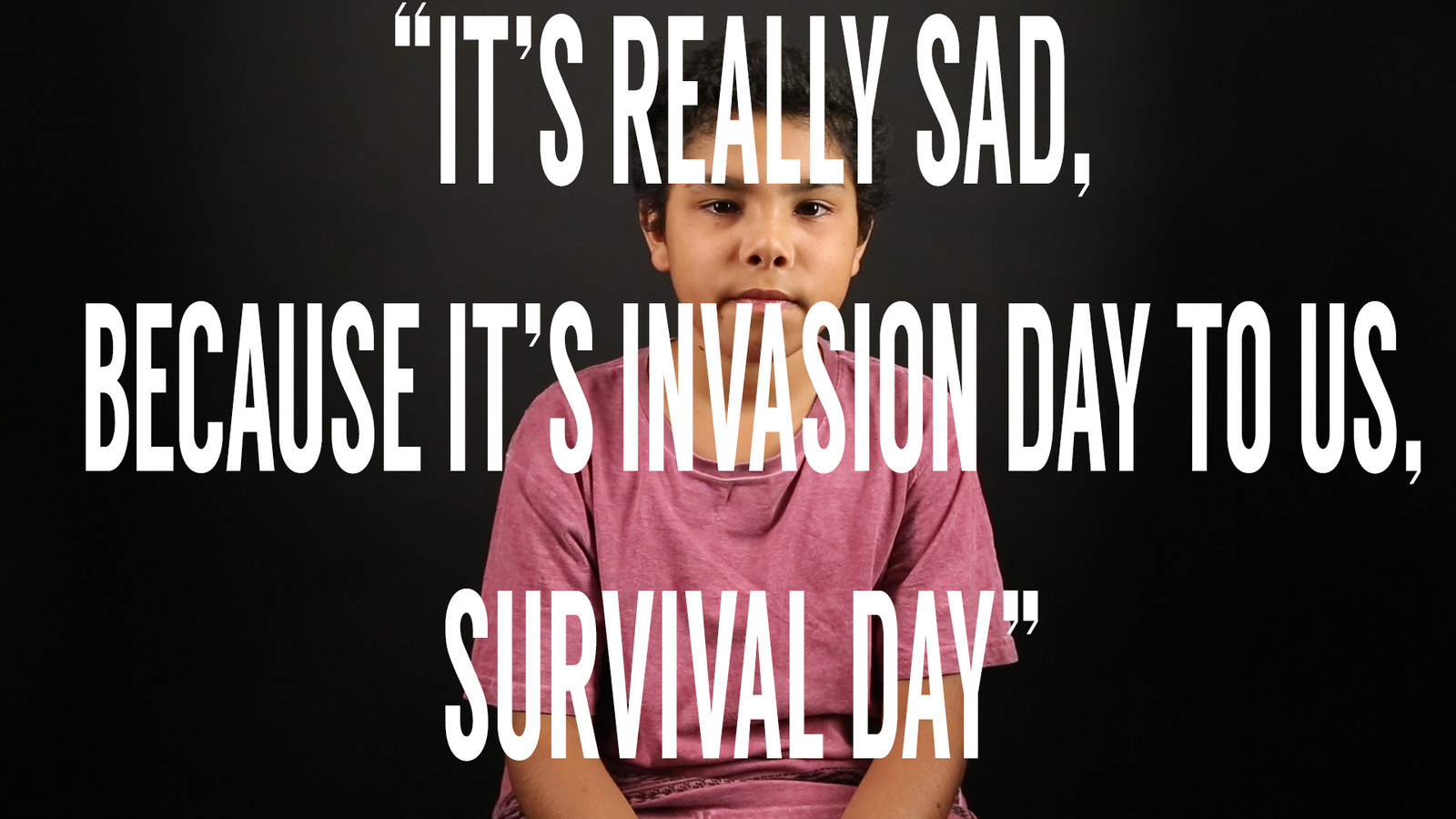

“It’s embarrassing. It’s like people celebrating the day that your people got slaughtered or invaded and really bad things happened. It’s really sad.”

"Slaughtered" and "invaded" are incredibly jarring words when delivered in a soft tone.

This is what Mirrabee Al-Abr, a 13-year-old Aboriginal boy from New South Wales, is feeling and thinking while the rest of the nation is celebrating the creation of the first British colony on the Australian continent.

Mirrabee says it without malice or anger – the words just float from his mouth. His young mind drifts to his ancestors and the pain they must have felt during the early years of the colony.

Sipping on a can of Coca-Cola in BuzzFeed's Sydney office, the teenager scans the room. He's polite and intelligent, and looks much younger than his age. Yuin and Wiradjuri blood runs through Mirrabee's veins and it's an ancestry that he's fiercely proud of.

We're chatting to Mirrabee just a few minutes' walk from the shore of Port Jackson in Sydney, where Captain Arthur Phillip landed on 26 January 1788 to claim New South Wales for the British Empire.

“[I get really] angry and annoyed," he says. "It’s really annoying because they’re celebrating the day of your people being slaughtered and the day that caused all that destruction and all that suffering to a very peaceful people."

Mirrabee's thoughts on Australia Day are widely shared throughout the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community. Whether in the most remote region of Western Australia or the heart of the nation's biggest city, most Indigenous people think of 26 January as Invasion Day or Survival Day, or both.

BuzzFeed News asked several Indigenous men and women from across the country what Australia Day meant to them. Those interviewed were from different tribes and nations and ranged in age from 13 to 50.

Overwhelmingly, those questioned said they saw 26 January as a day of invasion and survival. All questioned why an alternative date was not used to celebrate the modern nation of Australia, one on which they could celebrate along with everyone else.

Instead, January 26 causes anxiety and tension for the majority of Aboriginal people, forced each year to run a gauntlet of over-the-top jingoism as smoke from countless barbecues mask the bloody history of atrocities that followed 1788.

"It's like somebody that comes into your house, does horrible things to your family," Kuku Yalanji and Wemba Wemba man Bjorn Stuart, 28, tells BuzzFeed News, "and they're like, 'Dude, we're going to have a party and have a BBQ and listen to Triple J and we're going to put it on the date we turned up.' That's kinda sadistic, man, why would you do that?"

Murruunyandahl Leha, 16, says, "The fact that they celebrate that day that we lost all that we had, it pisses me off."

For Bidjara elder Ken Canning, "It's the day that marks the beginning of the massacres."

Gomeri man Colin Kinchela advocates for a different date: "If it's truly a celebration of what we are as a nation than we need to include the first nations of this country."

That sentiment is echoed by Yuin and Wiradjuri woman Angeline Penrith: "We are quite inclusive people. We just want to be included too."

During the spring of 1787, British King George III, infamous for his mental illness and the loss of British control of the American colonies, pressed the nib of a quill on to a piece of paper. As the black ink swirled into a signature, the fate of Aboriginal people 17,000km away, who had been living on the Australian continent for tens of thousands of years, was sealed.

Unbeknown to the more-than-500 Aboriginal nations – each with their own language, complex kinship system, and cultural traditions – their land been declared the property of the British Empire.

Passed through parliament, approved by the King, and on advice from his Privy Council, a letter of commission written by Lord Sydney on 15 April 1787 was handed to veteran Royal Navy officer Captain-General Arthur Phillip.

"To our trusty and well-beloved Arthur Phillip Esquire," the letter reads. "By these presents do constitute and appoint you the said Phillip to be our Captain-General and Governor-in-Chief in and over our territory called New South Wales."

At the time, the New South Wales colony encompassed what are now known as the four Australian states of Queensland, NSW, Victoria and Tasmania, plus large swathes of South Australia.

In 1770, Captain James Cook had surveyed the entire eastern coastline of Australia and claimed it for England under the doctrine terra nullius, a Latin phrase meaning "nobody's land". In the 18th century, there were only three ways England could claim territory under European international law. Terra nullius was one of them.

The claim of terra nullius was false. Cook himself had written extensively in his diary about the many Indigenous groups he had encountered during his expeditions and their way of life. His diary reveals these interactions in vivid detail, including the first time he met the people from the Eora nation living around modern-day Sydney's Botany Bay.

Cook wrote: "Saw, as we came in, on both points of the bay, several of the Natives and a few huts; Men, Women, and Children on the South Shore abreast of the Ship, to which place I went in the Boats in hopes of speaking with them, accompanied by Mr. Banks, Dr. Solander, and Tupia. As we approached the Shore they all made off, except 2 Men, who seem'd resolved to oppose our landing."

The two Aboriginal men refused to let Cook come ashore even after being thrown "nails, beads" as presents. They remained staunch and continued defending the beach. After the men threw a rock at the boat, Cook began shooting at them with a musket.

" I fir'd a musquet between the 2, which had no other effect than to make them retire back, where bundles of their darts lay, and one of them took up a stone and threw at us, which caused my firing a Second Musquet, load with small Shott; and altho' some of the shott struck the man, yet it had no other effect than making him lay hold on a target."

Eighteen years after Cook's Endeavour sailed out of Botany Bay, the First Fleet, led by Phillips, sailed into Port Jackson, now better known as Sydney Harbour.

Eleven ships carrying more than 1,480 men, women, and children, the majority of them convicts, must have been bewildered by the rugged bushland that tumbled down the sandstone cliffs to the edges of the blue shimmering harbour.

Under a blazing hot summer sun on 26 January 1788, Phillip set foot on Sydney Cove, planted a union flag in the soil, and began creating a penal colony designed to alleviate the overcrowding in Britain's swelling jails.

In the years that followed, the colony's relationship with the local Gadigal people shifted from tension to outright conflict as Indigenous people fought for control of their homelands.

Conflicts now known as the "frontier wars" played out across the colony. Soldiers and early settlers moved inland looking for farming land. Their expansion was at times violent: Numerous massacres of Indigenous men, women and children took place, and punishments were meted out to Aboriginal people in often lawless places.

One of the more well-known massacres was that of Myall Creek, NSW, in 1838.

On 10 June, a group of convict stockmen tied 30 Wirrayaraay women, children, babies, and old men together by their necks and led them to a gully where they were brutally murdered. Slashed, hacked, and beheaded by machetes and knives, their bodies were later burned.

The attack was premeditated – the stockmen attacked the group while the Wirrayaraay men were out working on a nearby station.

Eleven men were bought to trial in Sydney and initially found not guilty by a jury and freed. One of the initial jurors quoted in the now defunct Australian newspaper said, “I look on the blacks as a set of monkeys and the sooner they are exterminated from the face of the earth, the better.

"I knew the men were guilty of murder but I would never see a white man hanged for killing a black.”

Seven of the accused would later be found guilty and hanged.

The grotesque crime captivated Sydneysiders and it was widely reported at the time. While there were small pockets of outrage amongst the colony, overwhelmingly the public sentiment was on the side of the killers.

In an article titled "The Blacks" in the Sydney Morning Herald, 1838, a journalist writes, "We want neither the classic nor the romantic savage here. We have far too many of the murderous wretches about us already.

"The Colonists require an efficient itiner-ating mounted police force to preserve their property from being plundered or destroyed, and the lives of their servants taken by these 'interesting' creatures."

"The whole gang of black animals are not worth the money the colonists will have to pay for printing the silly court documents on which we have already wasted too much time." – Sydney Morning Herald article, 1838

"That day [Australia Day] actually marks the day of colonisation, the day of invasion. And whether it’s appropriate or not [to celebrate], it’s up to people to decide that for themselves" – deputy NSW opposition leader Linda Burney

MP Linda Burney, NSW deputy opposition leader and the first Aboriginal person to be elected to parliament in the state, has a quietly authoritative voice. Over the phone she tells BuzzFeed News that like many Australians, she has conflicting emotions about Australia Day. As a member of the NSW parliament, she's encouraged to attend Australia Day events and will be presiding over Australian citizenship ceremonies. She loves seeing the joy in the eyes of new Australians, but as a Wiradjuri woman, for her the day is also one of sorrow.

"It’s an uneasy day for Aboriginal people – it means something very different to Aboriginal people," Burney says.

"There will always be the discussion whether January 26, and I’m on record saying it, would be preferable to be on another day that's more unifying for all Australians, and of course, that’s a sentiment that’s expressed by many people, not just Aboriginal people."

Twenty-eight years ago Burney was an activist and one of the organisers of the huge 1988 Bicentenary protest march.

The multimillion-dollar Bicentenary celebrations in Sydney on 26 January that year commemorated 200 years since the arrival of the First Fleet and the unfurling of the union flag on Eora soil.

The harbour was virtually unrecognisable from that of 1788, walled in by a row of looming skyscrapers. Prince Charles and the late Princess Diana, wearing "Bicentennial green", greeted an adoring crowd, and a re-enactment of the First Fleet sailed into the harbour.

On the other side of the city, a swelling and heaving mass of more than 40,000 protesters made their way through the arteries of Sydney's CBD towards Hyde Park.

"It was amazing; I’ll never forgot that morning," recalls Burney. "All the convoys came in – there were people coming in from all parts of Australia, they’d travelled across the country for days and days."

On the "march of freedom, justice, and hope", Aboriginal protesters were joined by thousands of non-Indigenous people in the largest protest Sydney had seen since the Vietnam moratorium of 1970.

Australia Daze, a 1988 documentary about the Bicentenary, features a young Burney with her head wrapped in an Aboriginal flag before the march.

"Well, today we are going to make history in this country," she says, "because a whole group of people, a whole stack of people, have been organising for over a year and half now for the march for freedom, justice, and hope."

"It’s not an empty land. It is a land that has been occupied since time immemorial. The problems that were created because of the arrival of the first fleet are still very much the problems we still face today – dispossession, poverty, second-rate citizenship. We want to bring that to the world's attention."

26 January has long been a day of protest for Indigenous Australians.

In 1888, 100 years after the founding of the original colony, Aboriginal leaders boycotted celebrations in Sydney in an effort to attract attention to their cause. They were ignored by authorities.

On the 150th anniversary of the landing of the First Fleet in 1938, a group of Aboriginal people declared 26 January a "Day of Mourning" and marched through Sydney. It was an extraordinary move, given Aboriginal people were still under the control of the government at the time and would not even be counted in the census until the late '60s.

The Day of Mourning was organised by William Cooper from the Australian Aborigines League, William Ferguson, who established the Aborigines Progressive Association (APA), and Jack Patten, the president of the APA. The protesters marched in funeral clothes to a rally to hear speeches and voice their issues.

Around 1o0 people took part and quotes from Patton were published in The Australian Abo Call, Australia's first Aboriginal affairs publication; they still offer a powerful summation of the strange world Aboriginal people inhabit on 26 January.

"On this day the white people are rejoicing, but we, as Aborigines, have no reason to rejoice on Australia's 150th birthday," Patton said. "Our purpose in meeting today is to bring home to the white people of Australia the frightful conditions in which the native Aborigines of this continent live.

“This land belonged to our forefathers 150 years ago, but today we are pushed further and further into the background. The Aborigines Progressive Association has been formed to put before the white people the fact that Aborigines throughout Australia are literally being starved to death. We refuse to be pushed into the background."

"We have decided to make ourselves heard. White men pretend that the Australian Aboriginal is a low type, who cannot be bettered. Our reply to that is, give us the chance! We do not wish to be left behind in Australia's march to progress. We ask for full citizen rights."

“Historically, Australia Day is quite a new invention," says University of Sydney associate professor Catriona Elder, an expert in Australian cultural identity who has been researching the rise of alternative Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander events on Australia Day. "The idea of 26 January marking the British arrival in Sydney was seen as something quite specific to NSW for a long time and I don’t think every Australian cared."

Up until the large-scale and heavily government-funded 1988 bicentenary celebrations, Elder says, the majority of Australians remained ambivalent about the day.

“From 1988 onwards, with the money being put into it [Australia Day], along with creating a sense of history it [26 January] becomes more of a point of focus.”

As Indigenous Australians seek an alternative date of celebration, there has been a growing proliferation of Indigenous community-run events each year. One of the biggest is Sydney’s Yabun festival, which attracts thousands of visitors, many non-Indigenous.

“That’s the other thing that Australia does – it erases this thing called Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander history and starts the clock on January 26, 1788, which is a powerful refusal of the original people," Elder says.

“Australia Day is not going to go away, in the sense that the Australian government and lots of people don’t want to change the date, so you have Aboriginal people who come up with alternative ways to think about it, so that’s things like calling it Survival Day and Invasion and also producing alternative spaces to be in."

While the date is unlikely to change, the past few years have seen more inclusion of Indigenous people in official Australia Day ceremonies.

This year organisers have said there will be a stronger emphasis on Indigenous recognition.

In Sydney, the day will start with the WugulOra [meaning "one mob" in Eora] ceremony. The Aboriginal flag will be raised on the Sydney Harbour Bridge, from where Aboriginal pop star Jessica Mauboy will sing the national anthem in both local Indigenous language and English, while audiences around the country watch her via a live broadcast.

"Increasingly non-Aboriginal Australia is understanding the feelings of the Aboriginal people on the day our lands were invaded and colonised," Burney says.

As the nation becomes awash with green and gold and thousands drape an Australian flag across their shoulders and sing the line “Australians all let us rejoice / For we are young and free”, Aboriginal people will be gathering in parks and streets across the country, just as they've done for over a century on 26 January.

Thirteen-year-old Mirrabee Al-Abr won't be at the harbour; he'll be at a Survival Day concert, one of many held around the country, on the other side of the city with his family and the Koori community.

"I don’t want to be put on a show. I don’t want to be referred to as native Indigenous. I want them [the non-Indigenous population] to acknowledge that I come from here. You should respect our law, not the law the government has, but spiritual traditional law [of the Aboriginal people]."

This year – like every year since 26 January 1788 – Aboriginal people will protest and mourn for the land that was taken off them under the guise of terra nullius and pay tribute to those killed in the countless atrocities following the First Fleet’s arrival.

But, as always, Survival and Invasion Day events are also about inclusion. Non-Indigenous people of all backgrounds are welcomed with open arms and kindly asked simply to consider and reflect on what the day means for Australia’s first people.

View Survival and Invasion Day events taking place around the country here.