Theresa May launched an audacious bid to win the entire centre ground of British politics on Thursday as she unveiled an election manifesto that acknowledged the power of government to do good and explicitly disavowed the Thatcherite touchstones of free markets and “selfish individualism”.

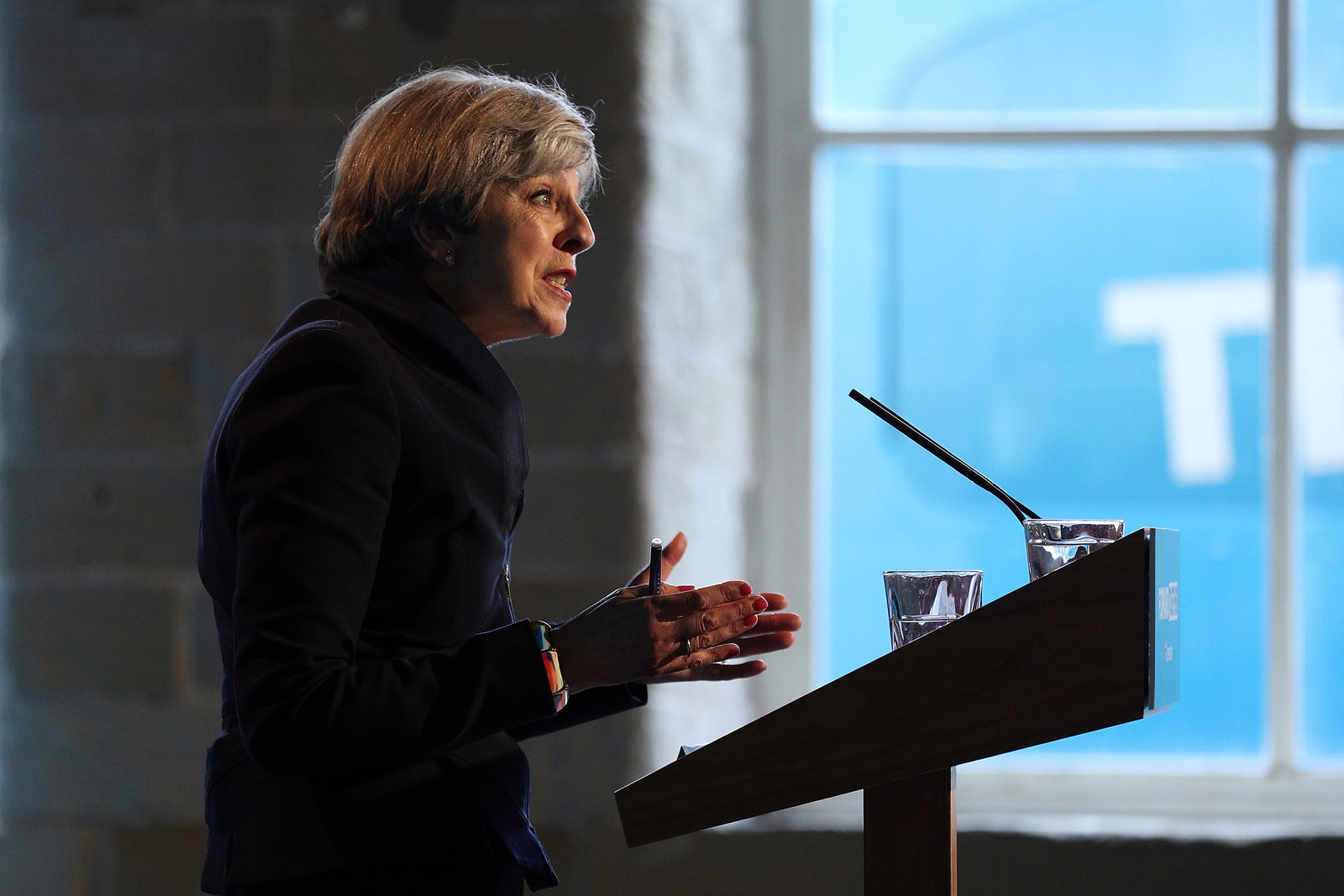

Four weeks into a campaign that has centred almost exclusively on selling May’s personal attributes – and an endlessly repetitive promise to deliver “strong and stable leadership” – the Tory leader made her pitch to disaffected voters from both Labour and UKIP.

In a sign of how confident May’s team are of victory on 8 June, the manifesto distanced the Conservative party from some of its core ideological beliefs, signalling a more interventionist, nationalist approach than that of her predecessors – even if it means disappointing the base.

Launching the manifesto in Halifax, a marginal Labour seat, May rejected comparisons to Margaret Thatcher and insisted she would govern for the “mainstream of the British public”, not for vested interests or based on any fixed ideology.

“There is no Mayism,” the prime minister insisted in response to questions from journalists trying to pin down her political philosophy. “There is good, solid conservatism which puts the interests of the country and the interests of ordinary working people at the heart of everything we do in government.”

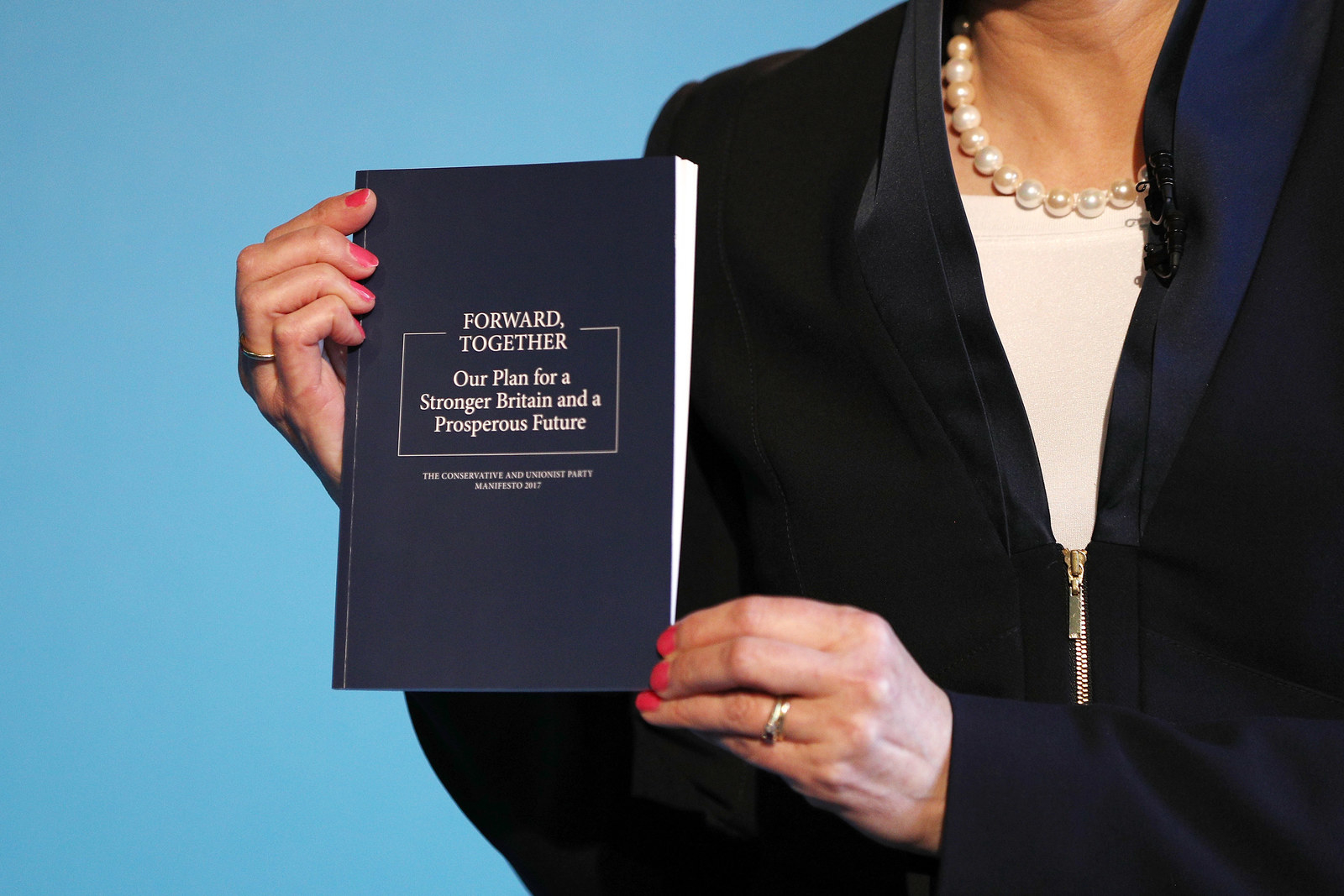

With just just three weeks to go till polling day, May finally unveiled her party’s policy platform at a former industrial mill. Declaring a vision for turning Britain into a “great meritocracy” in the next five years, it was a document designed to reach beyond the Conservatives’ traditional supporters and appeal to voters who previously backed other parties.

On the face of it, the manifesto was a bold repudiation of the free-market-oriented strain of Thatcherism that has underpinned the party for decades. Promises to end racial and gender injustices, protect consumers, and bring corporate interests to heel could have been lifted directly from Labour.

The manifesto clearly reflects the thinking of Nick Timothy, May's co-chief of staff and policy architect, who coordinated the document. The son of a Birmingham steel worker, Timothy has criticised the party for representing the upper classes and commercial interests while ignoring voters in the sort of working-class suburb where he grew up.

“Injustice is a scar on the soul of our nation and I will fight it wherever it is found,” May said at the press conference, in a line that could have been lifted directly from one of Jeremy Corbyn’s speeches.

“We do not believe in untrammelled free markets,” the manifesto stated, in another line that seemed more Labour than Tory. “We reject the cult of selfish individualism.”

From now on, May said, the party will be governed not by ideology but by a pragmatic adherence to what works.

The party will reject “ideological templates provided by the socialist left and the libertarian right”, the manifesto stated. Rigid adherence to ideology was not only needless, but dangerous.

Instead, May plans to “govern from the mainstream”, the manifesto declared.

With no Conservative manifesto to debate before today, the campaign has instead focused on the supposed inadequacy of Labour’s platform and May’s personal attributes as a leader. Those who were hoping to discover more about what will underpin her policy agenda for the next five years if she gets re-elected got their answer on Thursday: whatever the prime minister thinks is best.

“There will be no ideological crusades," the manifesto said. "The government’s agenda will not be allowed to drift to the right. Our starting point is that we should take decisions on the basis of what works.”

Instead, May will move left and right simultaneously, unafraid to provoke traditional Tory voters.

It's a populist appeal to the “ordinary working families” May promised she would reach out to when she won the Conservative leadership last summer, after Cameron resigned in the wake of the Brexit vote. Those are the hard-pressed voters who are worried about losing their jobs, paying the mortgage, and getting their kids into a good school, who feel that Westminster doesn’t understand their concerns.

It's also a pitch designed to appeal outside the traditional Tory base – hence May’s repeated visits to marginal Labour seats in areas like Yorkshire and the Midlands during the campaign. With a vast lead in the polls over Corbyn, May’s team are calculating that they can reach both to the left and right and seize the centre ground of British politics for a generation.

But the document appeared to go beyond political calculation. There had been speculation that, with such a commanding lead in the opinion polls, and a much larger victory assured, May could get away with publishing a short document that promised very little, in order not to be caught out down the track if she breaks a promise. As it turned out, the document was more than 84 pages long, and had a more strident tone than many expected.

Ryan Shorthouse, director of Bright Blue, a Conservative think tank, said: “This, finally, is the flesh of Mayism: a communitarian approach, prizing citizenship, country and civic service. It puts to rest the idea, lurking since the Thatcher era, that conservatism is simply about shrinking the state. This is a thoughtful and passionate case for a supportive and strategic state.

“It sounds good, but the substance is sometimes lacking, especially on improving the incomes and rights of workers. In places, it also plays petty politics. It takes a dig at elites, which is hardly meritocratic. And it recommits to a hardline approach on immigration that threatens Britain’s prosperity and sense of fair play."

The document set out five big challenges facing Britain in the next five years: the economy, Brexit, social divisions, an ageing society, and disruptive technological changes.

There was red meat for the Conservative base: promises to maintain defence spending, keep taxes “as low as possible”, reduce corporation tax to 17% by 2020, and end “poor and excessive government regulation”.

May’s commitment to Brexit will please the Eurosceptics. Her earlier assurances that Britain will leave the single market when it comes out of the EU, despite many analysts saying it will damage the economy, are now in black-and-white – although the manifesto didn’t say anything about leaving the European Court of Justice, another bugbear of the hardline Brexiters.

In other areas, however, May displayed a far greater willingness to allow state intervention than many of her predecessors – and many in her cabinet – will find comfortable.

Espousing a view that government can be a force for good, the manifesto said the Conservatives would look at introducing new protections for consumers (such as a ban on companies cold-calling people to tout for personal injury claims), maintain rights for workers guaranteed by EU regulations, and, perhaps most ambitiously, even attempt to regulate the internet. (“We will be the global leader in the regulation of the use of personal data and the internet,” it says.)

A £23 billion national productivity fund will direct new investment into housing, research and development, and economic infrastructure, the manifesto promised. Legislation would be introduced to protect the victims of domestic violence and redress inequalities in race, gender, and mental health. More than 1 million disabled people would be given jobs. The Conservatives would even end rough sleeping within a decade. A “significant” number of civil servants would be moved out of London to ensure the government becomes less out-of-touch with the people it represents.

There were policies that won’t go over well with big business. Mergers and takeovers could be paused so the government can assess whether they are in the national interest. May’s hard approach to immigration, including charging companies £2,000 for every migrant they employ, will “worry companies of every size, sector, region and nation,” the British Chambers of Commerce warned. And proposals for new employment regulations “will be questioned even by firms that are not directly affected themselves, because of the signals they send”.

May’s biggest concession to the populist mainstream is her controversial decision to maintain Cameron’s promise to reduce net migration to the “tens of thousands”, against the objections of her ministers, who see it as an impossible target to meet that only creates political headaches, and analysts, who warn it will damage the economy.

In her long career in politics, May has earned a reputation for being willing to tell uncomfortable truths, famously admonishing her party to shed its reputation for being “nasty” and taking on the police when she was home secretary. So commanding is her lead in the opinion polls that she can do it now without risk of rebellion from within the Tory ranks.

Critics who say May’s campaign has been too focused on her “strong and stable leadership”, with not enough policy detail, are unlikely to have been satisfied by today’s appearance. The prime minister’s speech was again heavy on rhetoric, repeating well-worn lines, and the manifesto was light on detail about her plans for some of the most pressing challenges facing the country – notably Brexit and the NHS.

Adam Marshall, director general of the BCC, said: “The manifesto recognises that the UK needs a strong economy, stable public finances, a strong domestic business environment and outward-looking trade policies to weather the Brexit transition and develop a new model for growth. However, the document includes few specifics on how these important goals will be achieved.”

The Tories’ political rivals attacked the manifesto as mean-spirited, citing the end of free school lunches for infants, the end to the “triple lock” on state pensions, and making the elderly pay for their own social care if the value of their home is more than £100,000. "Theresa May is betraying working families by snatching school lunches from their children and their homes when they die,” Ed Davey, of the Liberal Democrats, said. "The nasty party is back – hitting families from cradle to grave."

The Trades Union Congress said May’s manifesto would allow workers’ rights enshrined in EU law to be watered down after Brexit, and that the Conservatives would do nothing to help “hard-pressed public servants who’re facing more years of real-terms pay cuts”.