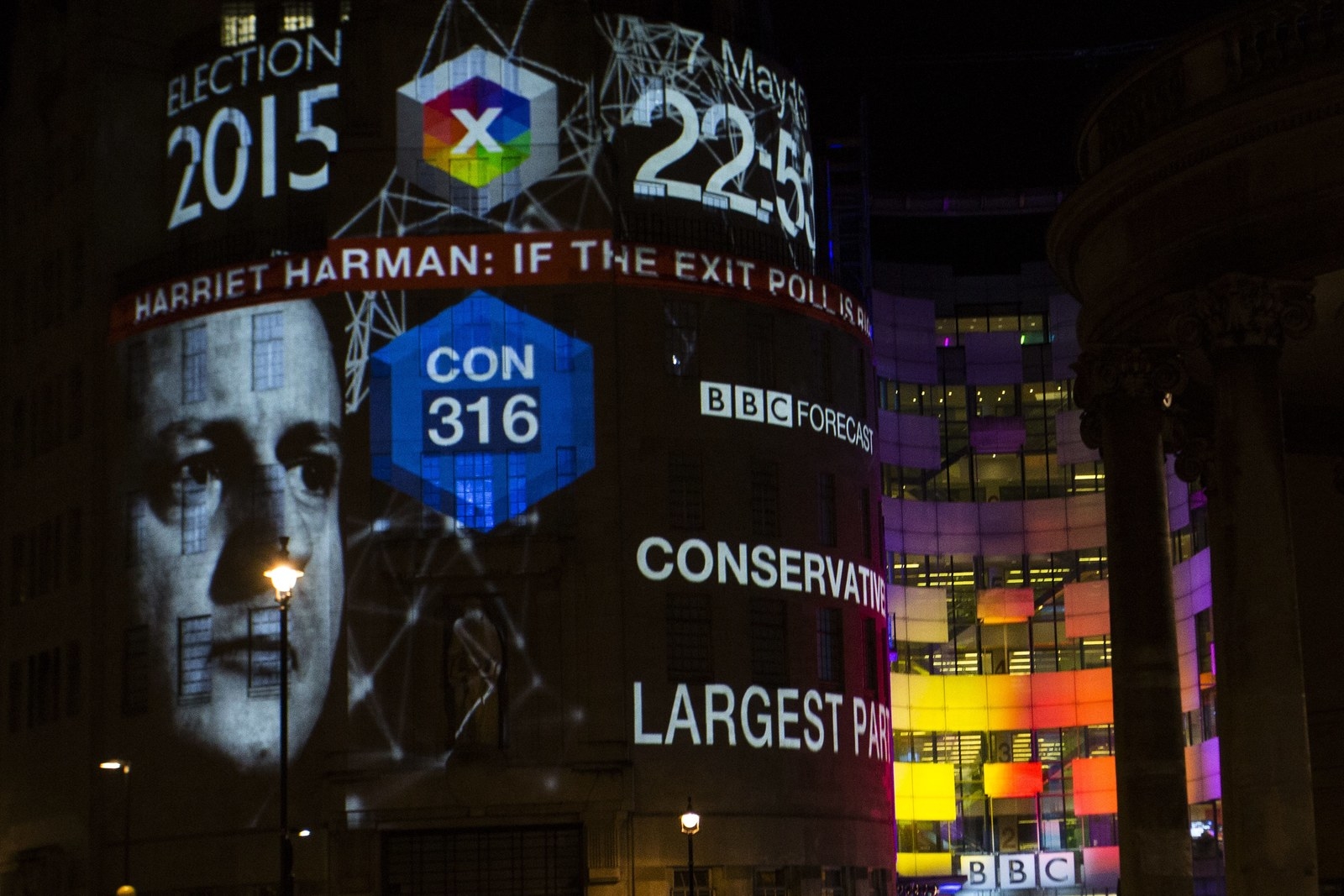

As late as 9:59pm on 7 May 2015, the UK was preparing for a hung parliament. For weeks, driven by poll after poll showing a contest too close to call, there was talk of a constitutional crisis, of multiparty coalitions, and of what kind of prime minister Ed Miliband would be. Then, at 10pm, the BBC's exit poll dropped, showing the Tories as the largest party. By the next morning they had won an outright majority for the first time since 1992.

The polls, the media, and the vast majority of commentators had told the story of an election that never was. Egos were bruised, reputations left in tatters.

BuzzFeed News spoke to pollsters and experts about what they have done to remedy what happened two years ago, what factors of uncertainty remain in the context of an election that isn't expected to be close, and what the numbers, a month out, might suggest in terms of the size of Theresa May's mandate come the morning of 9 June.

They are hoping that this will be the election that enables them to win back the public's trust.

So what are they doing differently this time?

An independent inquiry set up in the wake of the election found the primary cause of error was that those surveyed were not a representative selection of the nation’s voters: Samples had systematically overrepresented Labour supporters and underrepresented Conservative supporters.

For example, samples had too many younger voters with a greater interest in politics than most other young people, while they didn't have enough older people (who tend to vote in greater proportions compared with other age groups) and people who simply aren't very engaged in politics.

Much of the polling firms’ efforts have been dedicated to identifying, and better reaching, these types of people, and those who had eluded their surveys in 2015: the less engaged, the less educated, and the not very interested in politics. On top of this, the way raw data is adjusted has also been tweaked to better reflect the nation's demographic makeup, and to take into account new variables, such as education levels.

With less than a month to election day, the Tories are leading Labour by nearly 20 points. The size of their lead is such that if it remains intact over the next month, the polling error would need to be greater than the historic mistakes of 1970, 1992, and 2015 (which were all wrongly called for Labour) combined for Jeremy Corbyn's party to emerge victorious, according to analyst Matt Singh, one of the few experts to correctly predict the last general election.

If the numbers don't change, the Conservatives will almost certainly win the election.

On the surface of things, polling's task might appear easier this year because the polls could be even less accurate than in 2015 and, as long as the Conservatives win, many sitting in the stands might not even notice possible errors.

But pollsters will not only want to call the right winner, they will want to be accurate: for all the parties' vote shares to closely mirror what the polls are showing. If a poll shows a 20-point lead but the election outcome ends in a 10-point or a 30-point win, the poll is inaccurate even if it predicted the right winner.

The effects of the changes made by pollsters since 2015 are not yet fully known, and there are a number of factors, such as the impact of Brexit on voting intention, as well as margins of error, that add some degree of uncertainty to the size of the likely Tory win.

Most importantly, what polls aren’t set up to directly answer is how vote share translates into seats. In Britain’s first-past-the-post voting system, this is the all-important question. Various models will use polling data, alongside other variables, assumptions, and judgment, to produce seat forecasts but it is not impossible to have a situation where the polls are right and a model isn’t. (Most predictions currently see the Conservatives' potential majority well north of 100 seats).

But haven't the polls been wrong every time since 2015?

No. After Britain’s vote to leave the European Union and the election of Donald Trump in the US, the notion that “polls are wrong” took hold among many commentators, and in the minds of many voters and Twitter users.

In part, this has to do with the fact that, by and large, the way polls are written about and explained to the public hasn’t changed since the 2015 election.

Much of the debate about whether polls can be trusted has been tainted by confusion between what polling actually does and what amounts instead to poor interpretation of statistics and misunderstanding probabilities and uncertainty, as well as bad punditry. During the recent French presidential election, maybe to overcompensate for a lack of caution in the past, a 20-point lead was treated by some like a two-point gap.

The vote to remain in the EU was presented as a firm favourite during last year’s Brexit referendum, despite polls throughout the campaign, especially online ones carried out by firms such as YouGov and Opinium, suggesting a close contest.

“The myth that 'the polls got it wrong' is pernicious and incorrect,” Adam Drummond, head of political polling at Opinium, told BuzzFeed News. “Yes, some polls did err badly but online polls in particular showed that it was a tight race and that a Leave victory was a very real possibility. Most polls in the final week or so put Leave ahead, but the certainty of forecasters and commentators was in no way supported by the data.”

(UK polls also accurately predicted that Corbyn would be elected Labour leader twice, and that Sadiq Khan would win in London.)

During this year’s election campaign, even the main political parties have tried to build on this myth, suggesting, for different reasons, that Corbyn might become prime minister. In reality, with less than a month to go until polling day, the Labour leader is extremely unlikely to become prime minister even if the polls end up being slightly wrong.

“In 2015 the polls were an average of 3.3% out, but only once, in 1992, have they been more than 4% out. Furthermore, no single final poll has ever been more than 6% out,” Joe Twyman, head of political and social research for Europe, the Middle East, and Africa at YouGov, said.

“So is there a chance that we are overestimating support for a given party, outside the normal margin of error you would expect? Our enormous amount of internal testing suggests not, and recent local election results back this up – but we won’t know for sure until 9 June.

“What I am certain of is that Labour are not currently ‘really’ on 40-odd per cent and the Conservatives are on 20-something.”

If anything, historical precedent would suggest the Tories could outperform the polls come election day, Chris Hanretty, a reader in politics at the University of East Anglia, said. “My (current) rule of thumb is to say that you should add one percentage point to the Conservative figure, and subtract one percentage point from the Labour figure. That's very roughly the degree to which the polls have underestimated the Conservatives (and overestimated Labour) in elections since 1979.”

"The picture painted by the polls is broadly consistent with the picture which came out of the local elections," Hanretty added.

In the wake of the 2015 debacle, one of the suggestions made to pollsters was to give greater emphasis to the link between the candidate voters prefer as prime minister and their voting intention: Despite the Conservatives and Labour level-pegging in the polls, a majority of voters were indicating that they trusted David Cameron more than Ed Miliband when it came to who they wanted to see in Number 10.

This particular measure doesn’t bode well for Corbyn.

“The Conservative vote share and Theresa May’s approval rating are very similar, so for that reason I’d be more confident of what polls are saying about the Conservatives than what they’re saying about Labour,” Opinium’s Drummond said.

He added: “Labour’s vote share in our last poll was 30% but only 21% approve of Jeremy Corbyn (61% of Labour voters) and only 18% prefer him as prime minister (again, 61% of Labour voters) to Theresa May, so that Labour vote is soft.”

However, other lessons from the past could mean that the idea of an impending Tory landslide could influence some voters' behaviour, especially if they believe that Corbyn stands little chance of becoming prime minister.

Ben Page, CEO of Ipsos MORI, told BuzzFeed News: “Some voters may feel uncomfortable giving the Tories quite so big a margin of victory, others may feel it is safe to vote Labour even though they don't want Jeremy Corbyn as PM if they are sure he can't win. In Margaret Thatcher's big wins in the 1980s, the polls found much bigger leads a few weeks before the election than she got when the time came. (But that wasn't because the polls were wrong; they tracked the narrowing gap and got the final result spot on. And Thatcher still won, and won well.)”

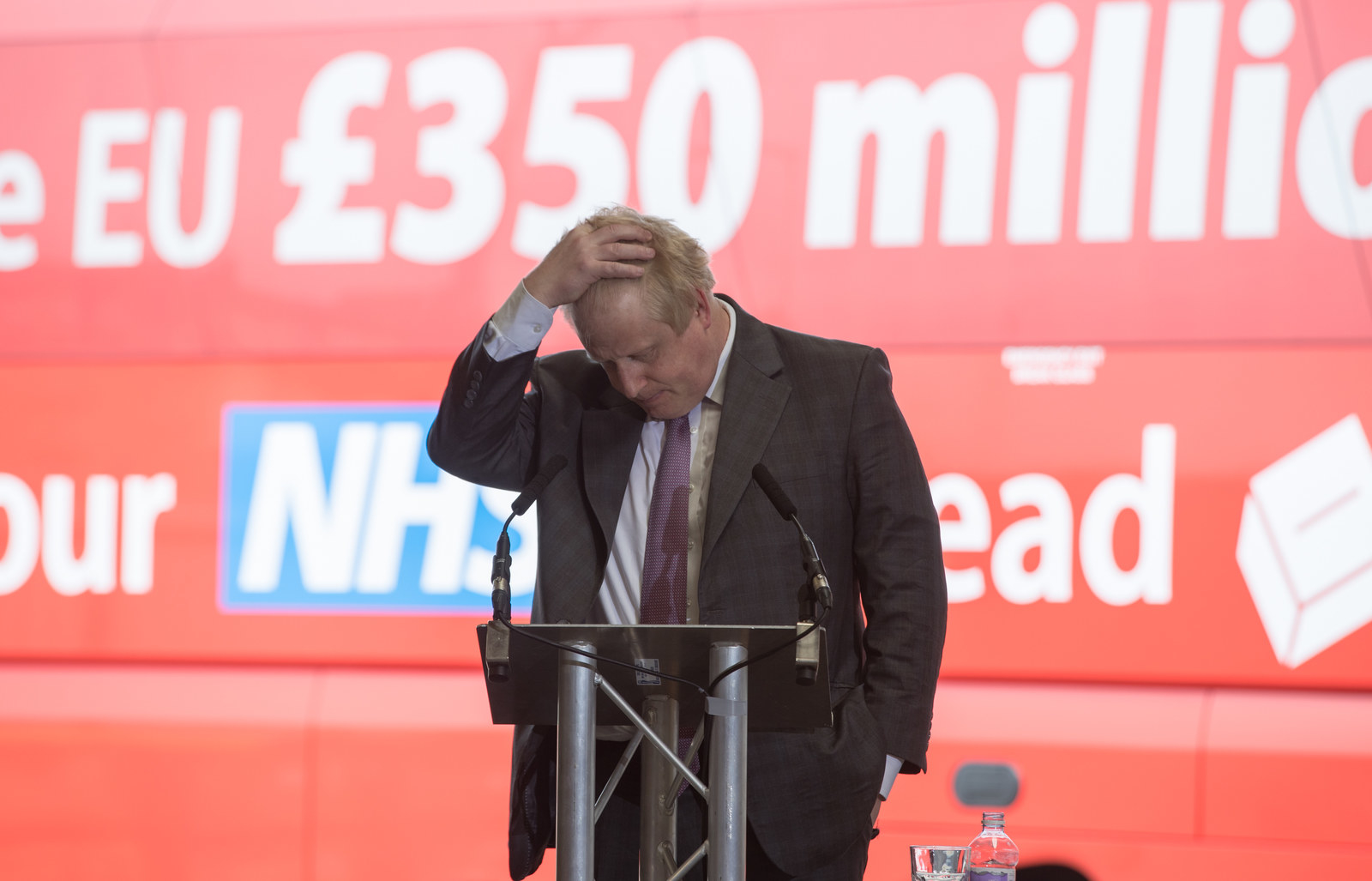

What impact could Brexit have on voting intentions?

There are a number of factors that add uncertainty to the figures that go beyond who will be returned prime minister next month. One of these is the impact the EU referendum and Brexit could have on traditional party loyalty.

“Every election brings its own risks, particularly when (as now) voters are less anchored to parties than in the past and major events like Brexit are shaking things up. There is some evidence – for example from Matt Singh at Number Cruncher Politics – that going on past vote intentions caused problems in 2015. It may cause problems again if Brexit shakes up loyalties,” Rob Ford, a professor in political science at the University of Manchester, said.

With Brexit accomplished, UKIP has so far been unable to explain what the point of its existence is. Meanwhile, the Lib Dem vote is showing little sign of taking off where it matters despite the party trying hard to win over people who voted to remain in the EU.

“All the polling since the election call – and the local election results – point to a collapse in the UKIP vote with most of it going to the Conservatives,” Ford said. “I don't see much reason for that to change – UKIP voters seem impressed by May’s embrace of ‘hard Brexit’ and the party is currently a bit of a mess in terms of organisation and resources.

“The Lib Dems’ vote share also does not seem to be rising in polls, and they did poorly in local elections because modest gains of Remain voters were not enough to offset the Conservatives’ much larger gains of UKIP Brexiteers. If this is repeated next month, the party could find itself with many extra votes, but few extra seats, or find itself losing as many seats in areas with large UKIP votes as it gains in heavily Remain areas.”

According to Opinium’s Drummond, polls currently show the Conservatives taking up to half of the 2015 UKIP vote, while the Lib Dems’ pitch to Remain voters has pick-up in metropolitan areas but is less effective in Leave areas in the South West constituencies the party lost in 2015.

Could turnout make a difference?

Another factor that polls have not always been able to anticipate accurately is voter turnout, primarily because survey respondents tend to overstate their likelihood to vote. And in 2015, polls oversampled more engaged voters. Since the last election, a number of firms have introduced new models that they hope will be better at capturing how many people will cast a ballot on election day.

In addition to the uncertainty of approaches that have yet to be tested in the wild, it is difficult to predict whether turnout will remain within a similar range to recent elections (about 60–66%), or whether voters will be galvanised by an election framed as a vote about Brexit and show up in greater numbers.

Conversely, election fatigue could kick in, and combined with the prospect of an outcome that is not really in question, people could be put off from voting. There could be a mix of motivations driving different groups’ decision to vote or not. For example, those enthused by the prospect of a global Britain under strong and stable leadership could show up in relatively greater numbers compared with those who think their party’s candidate doesn't stand a chance.

What will all this mean in terms of seats?

Despite the huge Tory lead, without detailed polling in marginal seats it is difficult to assess how nationwide polls and campaigns are playing out in key constituencies across the country.

Ultimately, how the Conservative vote performs in many of these seats, and how it is spread across the country, will determine the scale of May’s mandate.

And pollsters and experts are divided on how big they expect the Conservative victory, and May's mandate in the next parliament, will be.

“I'm not sure we can be certain yet that it will be a landslide,” Ford said. “Labour support is heavily concentrated in its safe seats, which will make it harder for the Conservatives to turn vote gains into seat gains.

“The pollsters made various changes to their methods to address their underestimation of the Conservatives and overestimation of Labour. We don't know yet what effects these will have – but it is possible that the pollsters overcorrect and we end up with an error in the opposite direction.”

Just as with vote share, others think the Conservatives could win more seats than a uniform swing – a measure that applies the same change in party support between elections across all constituencies – implies.

Page said: “The size of the Tory majority could be larger than some of the estimates. Look at the SNP in Scotland in 2015 – they spread their majority around rather than pointlessly piling it up in useless huge majorities wiping out Labour. If the Conservatives do the same a record-breaking majority is possible, but note that in the 1980s Mrs Thatcher’s large leads in the campaign shrunk by election day, despite her winning handsomely.”

Could anything change dramatically over the next month?

Polls aren’t predictions. They provide a snapshot of what people are thinking at that specific moment in time. With a month to go, some voters could, in theory at least, change their mind.

“A week is a long time in politics and we still have a number of ‘long times’ remaining until polling day,” YouGov's Twyman said. “Lots of things could still happen. In 2010 the Lib Dems jumped 10 points in a week, before falling back. That was after a TV leaders debate, the like of which we will not get this time, but it demonstrates the potential for things to change. This time around there are a combination of events we already know about and the inevitable surprise out of left field that mean the situation could change. As for whether it will or not? We don’t yet know. We will have to wait and see.”

But on the whole, a 20-point lead is a 20-point lead, it is not a toss-up.

We will not know until 9 June how accurate the polls are, but there is no evidence so far to suggest they’re wrong. For every Trump, there are dozens of other elections around the world – from the Netherlands to France – to prove that polling, however imperfect, continues to be a better barometer of public opinion than other measures such as gut instinct, betting markets, and the parable of Leicester City football club.

The University of Manchester’s Ford said: “As always, voters should view the polls as a usually reliable, but possibly imperfect, indicator. Polling is not an exact science. We can never know for sure that they will get the exact shares right. But they usually give a fair account of the overall state of play – and they are rarely wrong when one party has a very large lead. We saw this in the second round of the French presidential election, where Macron won by a large margin just as polling had suggested. If the Conservatives continue to have a large poll lead through the campaign, then while we won't know exactly how big their winning margin will be, we can be relatively confident that they will win.”

And what if Labour wins?

If the Conservatives go into election day with a lead of around 20 points, and Corbyn's Labour ends up winning the election and the keys to Downing Street, it will probably be curtains for polling in the UK.

Opinium's Drummond put it bluntly: “On the one hand a one-sided election is helpful for pollsters – because who remembers that polls in 1997 and 2001 overstated Labour enormously? On the other, if Labour do win when polls show the Tories 20 points ahead then it’s surely the end of political polling in Britain as a viable exercise and we should all pack up and go home.”

CORRECTION

The first exit poll at 10pm on 7 May 2015 showed the Conservatives as the largest party. It was only later adjusted, as initial results came in, to a Tory majority. The piece has been updated to clarify this point.