When former spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter, Yulia, were poisoned by Russian assassins on British soil earlier this year, the newly recruited team at BBC Serbian kicked into gear.

“When we were running stories on the Skripal case they were some of the best-read stories,” said BBC Serbian’s launch editor Aleksandra Nikšić. “We had the widest possible coverage of this case.”

A former war correspondent and editor at Vice News, Nikšić told BuzzFeed News during a trip to London that the new website’s “straight news” Skripal coverage filled a vacuum in the local Serbian press — where pro-Russian and anti-Western perspectives often dominate partisan tabloids.

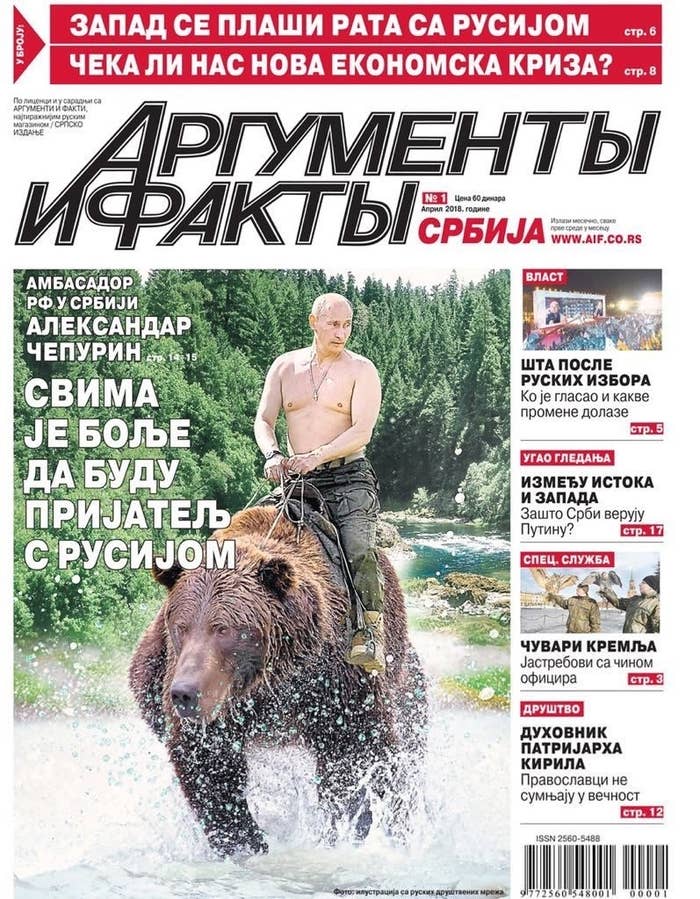

One Moscow-financed, pro-Russian magazine called Argumenty i Fakty Serbia, for example, used its first edition to dismiss allegations of Russian involvement in the Skripal poisoning.

According to the reliable English-language Balkan Insight website, one opinion piece in Argumenty i Fakty was titled “Poisonous Kiss of the West”, and praised links between Russia and Serbia, claiming: “Friendship in the West is a category narrowly limited by personal interest, selfishness, ruthlessness, disloyalty, hypocrisy and lies.”

Contrast that with the BBC approach. “We were carefully choosing the stories — relying on explainers,” said Nikšić. “We were presenting it as something that happened overseas that could have happened anywhere else; people were reading it.

“It was the information that no one was else was giving them.”

In 2011, UK government cuts had led to the BBC World Service closing its broadcast services in Serbia. But since then, Russia has illegally annexed Crimea, Serbia has taken steps to join the European Union despite scepticism among public opinion, and there’s been a global panic around Russia’s fake news and misinformation as well as its interference in other countries’ democratic processes. In April, the BBC World Service reopened the Serbian service.

BuzzFeed News has learned the original idea to relaunch BBC Serbian came from within the UK’s Foreign Office (FCO). According to two sources familiar with the discussions, Serbia did not feature in the World Service’s expansion plans until the FCO suggested it.

After Serbia was suggested by the FCO, the BBC carried out its own extensive independent assessment, per its regular process, which concluded that a Serbian service fulfilled its criteria for a new language service. Broadly speaking, the BBC divides markets on the basis of “need” — those countries where media is restricted — and “want” — where there is appetite for a calming voice amid a cacophonous media scene.

There is no suggestion that the BBC World Service’s independence or journalistic impartiality are undermined in Serbia or in any of the countries it operates.

BBC sources said the internal research revealed that Serbia had a brittle, underdeveloped media with a lack of unbiased and accurate news coverage. Local media experts say Kremlin-backed outlets such as RT and Sputnik have small audiences, but are widely quoted in the Serbian mainstream press, and the country is fertile ground for Russian disinformation campaigns.

Nikšić has hired seven, mostly young, reporters for the BBC in Belgrade. As well as their Skripal coverage, she points to the popularity of their stories about the Cambridge Analytica–Facebook scandal as early evidence the British broadcaster can cut through in Serbia.

“The local media landscape in Serbia is black and white,” she told BuzzFeed News. “You are either pro-government, or pro-Russian, or pro-whatever.

“This is the BBC’s chance to show that there is something in between. You don’t have to be a side.”

At the end of 2016, the BBC announced the “biggest expansion of the BBC World Service since the 1940s”, using part of a standalone £85 million grant awarded by the FCO to launch in an extra 11 languages, including Pidgin, Punjabi, and Korean. The funding was aimed at providing services in countries that had a “democratic deficit” through lack of access to impartial news.

That initial announcement made no mention of Serbia. However, discussions between the FCO and the BBC continued, and a month later the Western Balkan state was added to the list, and later announced. One BBC insider said the agreement was informally known internally among some staff as “11 languages + Serbia”.

The FCO grant to the World Service is a component of the government’s National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review, published in 2015. The plan, which describes Russia as a resurgent threat, sets out, among other things, how the UK can promote its values and interests globally through soft power.

The belief in Whitehall is that the best defence against disinformation is a robust, free, wide, and varied media landscape.

An FCO spokesperson said: “BBC News Serbian is the last of the 12 new language services launched as part of the biggest expansion of the BBC World Service since the 1940s. The expansion, which is funded through a grant from the UK government, also includes the enhancement of some existing services. Executive decision to launch, relaunch, or expand services lies with the BBC following extensive market and audience research.”

The investment, which reversed previous coalition government cuts, is up for review in 2020. BBC insiders suggest the funding is likely to be renewed.

The war in Ukraine, and Russia’s annexation of Crimea, is seen as a watershed moment in the government’s decision to reverse earlier cuts to the BBC. The effects of Russian disinformation in the Western Balkans were a key driver in the government’s decision to support the BBC’s return to Serbia, though not the only one.

The launch of the service was driven by three factors: the weakness of the Serbian media scene, increasing Russian influence in the region, and providing continuity to the UK’s approach to the region after Brexit, said a senior British diplomat who spoke to BuzzFeed News on condition of anonymity.

Ahead of launching any new service the BBC carries out in-depth research about new markets it’s considering.

BuzzFeed News understands that key findings in Serbia included that a majority of young people in the country didn’t know about the Srebrenica massacre, where 8,000 Muslims were killed in July 1995, and other war crimes committed by Serbian leaders during the war in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s.

Nikšić has said addressing this point has been a focus of the first few months of the relaunched BBC Serbian website.

“We published a history of the conflict in 90 seconds,” she said. “We could see the most viewers were people 18 to 24, and it’s understandable because they did not live through this war.

“They want their own impressions of the past.”

The BBC research also concluded that the Serbian media market lacked the most basic provision of accurate and unbiased news coverage, that a lot of outlets simply copy and paste from government press releases, and coverage of the wider Balkans region was very heavily skewed toward war and conflict.

Neighbouring countries only feature in national news inasmuch as they present a real or perceived threat to Serbia. Local news was also poorly served.

For example, when a major explosion happened at a chemical factory in a town 150km away from Belgrade, the only coverage was on national TV news, as there was no local outlet.

A few years ago, Serbia introduced new media laws aimed at modernising its media landscape. News outlets, which had been owned and supported by local government since the communist days, were privatised.

This has had some adverse effects, with the emergence of mini-tycoons controlling small media empires.

“Nobody is sure who these people are, and there is evidence some are politically driven,” said a British diplomat. “Journalists say they feel under pressure, [media outlets] get tax audits or don’t get advertisement.”

According to Nikola Tomic, a media consultant and former senior editor at a number of Serbian media outlets, the privatisation process wasn’t transparent, and there are now not more than a handful of people ultimately controlling all local media in Serbia. Pro-Russian, anti-EU websites, the ownership of which is not always clear, have been popping up and spreading; websites with hyperpartisan news links like kremlin.rs, komersant.rs and reporter.rs.

And Moscow-backed outlets such as RT and Sputnik have found fertile ground to pump out Kremlin propaganda, and see it regularly picked up by domestic media and national newspapers.

“[Sputnik and RT] are not very popular, but they are highly quoted by mainstream media in Serbia,” said Tomic. The majority of the country’s media outlets and tabloids also repeat the same pro-Russia talking points, Tomic added.

Tomic said: “It’s not always clear if these outlets are financed directly or indirectly by Russia, or whether there is a mixture of Serbian and Russian political business interests.”

Russia and Serbia have historically had a close bond. As the current government in Belgrade has set the country on a path to joining the EU, it has sought to balance voters’ lack of enthusiasm for the EU, mistrust of NATO, and its positivity towards Russia by maintaining strong ties with Moscow.

“Russia sees all this as an opportunity, and invests time and energy, more than money and trade, in Serbia with cultural diplomacy and media,” said a senior British diplomat.

Moscow has also been apt at picking away at divisions in the broader region. Russia was allegedly behind an attempted coup in Montenegro two years ago. Earlier this year, Russian diplomats were expelled from Greece after being accused of fanning opposition to a deal between Greece and Macedonia that will see the latter country change its name following a decadeslong dispute. The agreement paves the way for Macedonia to join NATO and the EU.

Polling shows that among Orthodox Christians in Serbia, Montenegro, and Republika Srpska, Russia’s favorability remains high.

“The added oomph is that Russia backs them on Kosovo,” the same diplomat said.

Kosovo unilaterally declared independence from Serbia in 2008. Most Western nations recognise Kosovo, but Serbia, and notably Russia, do not. A proposal to redraw the border between Serbia and Kosovo as a solution to end the dispute has been gaining steam in recent months, worrying key European governments, including the UK and Germany.

Despite the UK’s vote to leave the EU, Britain’s historic policy positions and priorities toward the Western Balkans, including supporting the region’s efforts to reform and join the EU, have remained unchanged.

“One of the things needed for that is media,” the senior British diplomat added. “One of the BBC’s advantages is it brings is a solid pipeline of news, which is not coming through tainted sources. It’s also about improving professionalisation, and the overall media atmosphere.”

As part of the UK’s efforts to signal that Britain is committed to the region in the long term despite Brexit, it hosted the Western Balkans summit, and has increased development aid and funds for the region.

One characteristic of Serbian media coverage, diplomats and analysts said, was the need to identify an “enemy”. The role has traditionally been reserved for the US following NATO’s bombing campaign in 1999. More recently, the EU has often been accused of interfering in Serbian politics.

However, over the past year, attacks on the UK in the Serbian media have featured heavily, especially as Britain has often found itself at odds with Russia, and is perceived as less influential than other nations, such as Germany, which hold similar policy positions.

“It is a reflection of circumstances,” said a senior British diplomat. “There’s the Brexit factor. You can kick the UK, not the Germans, and can go only so far after the EU as you want to join.”

The diplomat reflected: “If you decide not to go after the US and Trump, and you need to pull your punches with the EU, cannot mess with the Germans, and want a foreign power, why not have a go at the Brits?”

The BBC didn’t share specific audience numbers for the first few months for the new Serbian website. Its Facebook page has a growing audience of just over 12,000 followers. The broadcaster said the English-language BBC World News TV channel has a weekly audience of 400,000 in Serbia.

Against a febrile media and political backdrop, Nikšić said she’s focused on leading her small team toward long-term goals.

“The generation I belong to, we have worked through the wars and the media blackouts, we are somehow limited, technologically limited, because of the wars and sanctions,” she said.

“For my young journalists I am there to guide them, but they are also the audience, and they are going to live in Serbia for the next 50 years.”