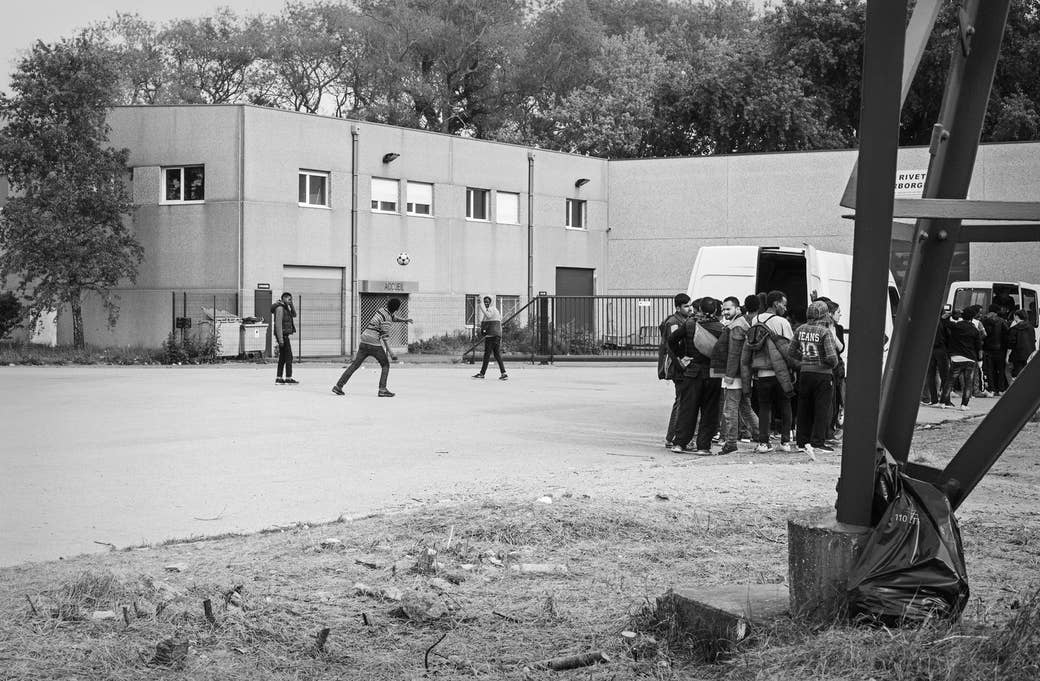

Under shadows cast by electric pylons, a group of young people sit on the grass near a motorway leading to the English Channel. Some play football with a stone on the gravel. Nearby are sand dunes and chemical factories, and chimneys dominate the grey skyline.

It is 6pm at the emergency distribution point in Calais, and many of the people waiting for food and other handouts are unaccompanied minors – people under 18 with no home, no shelter, and no guardians. Many are here to be given what will be their only meal of the day. Three cars from the French gendarmerie police pull up, watching.

A 17-year-old, Daniel, sits on a sandy mound, flip-flops on his feet, eating a meal of rice and stew on a paper plate. Daniel tells me about how he tries to sleep on the forest floor at night. Like the other teenagers I speak to here, he says he's unable to. “At midnight the police come running through the forest, they zig-zag from every direction. I don’t sleep each night.

“The police burn sleeping bags every day, every day. No sleep at all.

“Every day beat, every day [they] spray [us with pepper spray]. Life is bad. I want a date [to transfer to the UK].” Another young person joins the conversation, saying: “Everybody – too much stress. We need freedom. What’s the solution? What’s the solution?"

It’s been six months since the Calais "Jungle" migrant camp that housed 10,000 people was cleared, but Help Refugees, a charity working on the ground delivering emergency aid, says there are still about 200 unaccompanied people under 18 among those left in the area. They are largely from sub-Saharan Africa – Eritrea, Sudan, Ethiopia – as well as Afghanistan and Iraq. Most of them are hoping to cross the heavily guarded border to get to the UK.

“Many times I try to cross,” says Daniel, who's from Eritrea, a country with indefinite military service, forced labour, and what Human Rights Watch has described as one of the “world’s most oppressive governments”. “Maybe 15 times. Police one day put me in prison, one month. One time 45 days.” Yet despite this he is determined to get to the UK: “I want to study engineering. It’s good for the mind, and the new generation will build."

Some of the young people in Calais have family in the UK and the right to join them. But although the Home Office says more than 750 unaccompanied children from France have been resettled as part of the UK’s support for the Calais camp clearance, Philli Boyle, the Calais manager of Help Refugees, says the process for family reunification has been so slow that many minors “have lost faith in the system and the possibility of safely arriving in the UK via a legal route".

“If children are driven to considering other ways of getting to the UK to find sanctuary, it exposes them to great danger,” Boyle says.

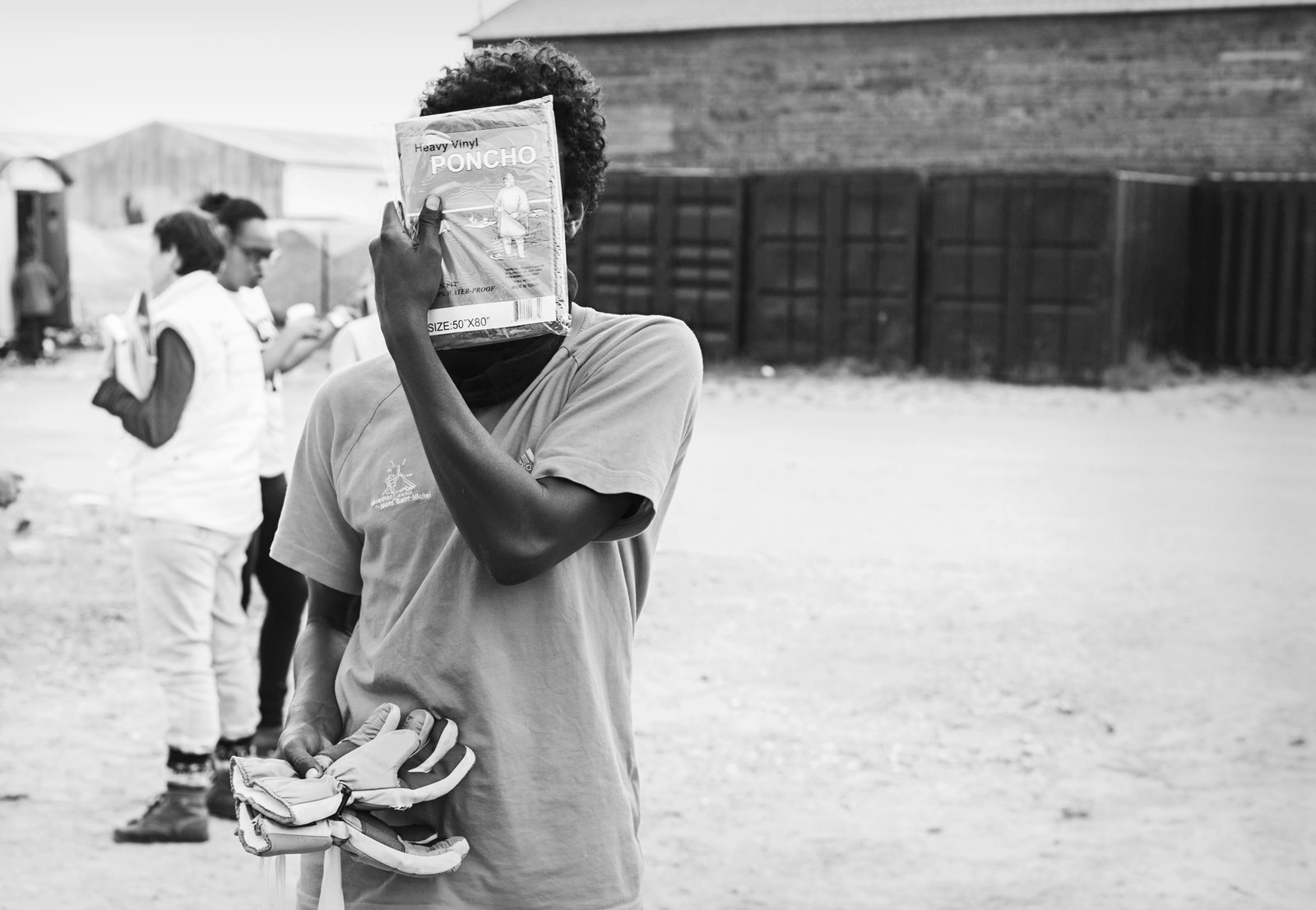

The volunteers say they hear police sometimes destroy the items they give out to the migrants. If the blankets are not lost or ruined in the rain, they've been told, police pepper-spray the bedding. As a result they hand out around 200 blankets every other night – far more than when there were 10,000 people sleeping at the Calais camp. “Everything we’re doing is fighting fires,” Josh, the warehouse distribution manager, says.

Beba, who is queueing up, is just 13, and says he has a sister in the UK. He says he wants to learn, have a social life and to play football. He supports Chelsea FC. He tells me his favourite player is Eden Hazard, the attacking midfielder. “I want to play football," he says, "but there’s no football, no stadium, just rocks.” What does he want to do when he grows up? “By trying and trying, I want to do every job. I lose my energy by police.”

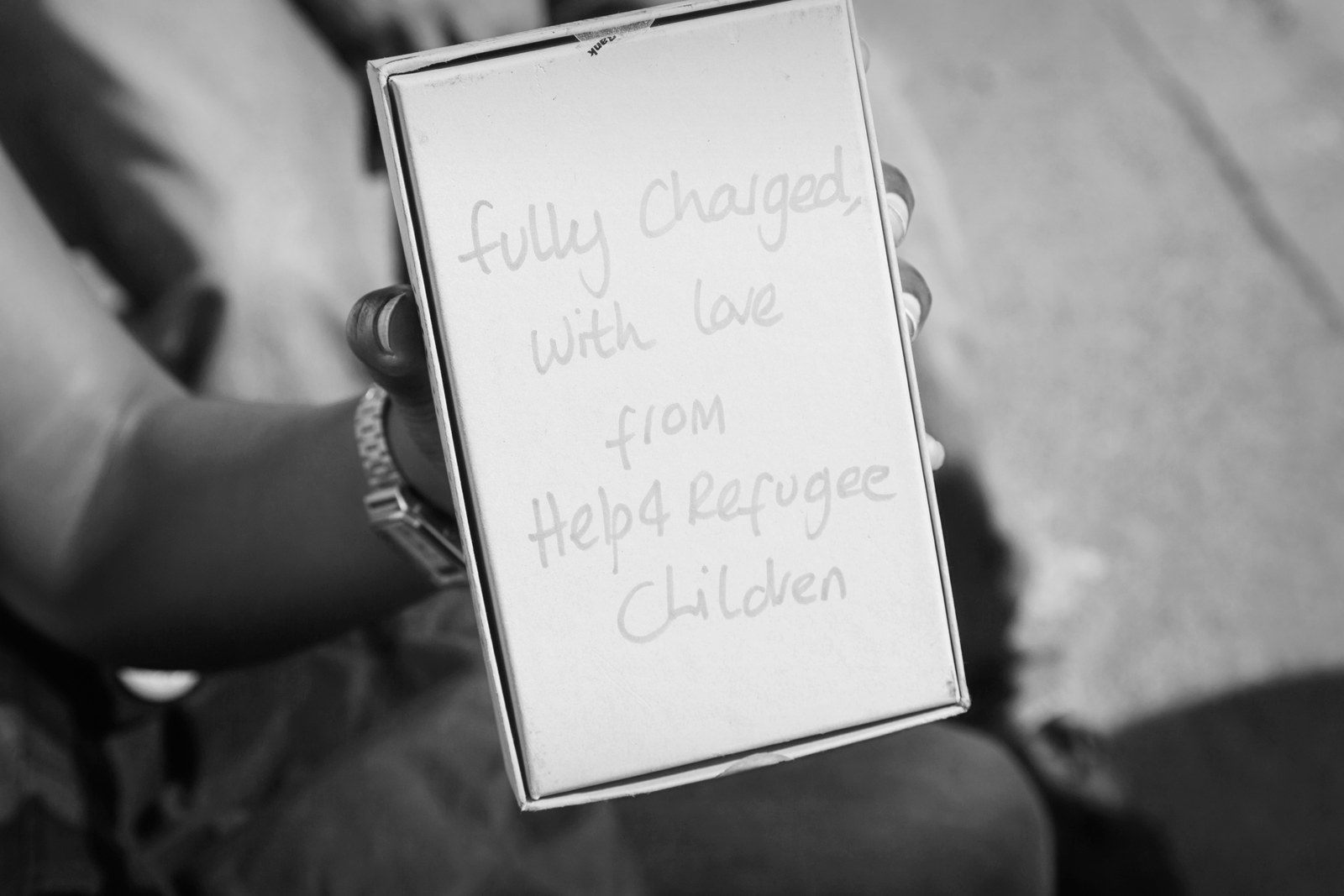

Charging his phone at the portable docks set up by the charity, Solomon Ayuub, 15, says he’s only been in Calais for four months, which means he arrived after the camp was demolished. He says this year's Ramadan, the Islamic holy month of fasting, which began this week, will be the first he's spent “away from home”. He has family in the UK and says he wants to do electrical engineering when he’s older. He says he sleeps in the “jungle” – a reference not to the defunct camp but the forest behind us, looming on the sides of the grassy clearing. “The police officer took our sleeping bag," he says. "France is a difficult country. Four days in prison."

When he was sleeping in the park, the gendarmerie came and he heard shouts of “Allez allez”, then was pepper-sprayed. One of his friends has crutches.

Thomas, 14, describes the home he left behind in Eritrea by miming someone holding a gun and shooting. He has had little sleep: “I’m afraid, I’m human, not an animal. Every night I cry, I miss my family.”

And then there is Samira (not her real name), a 17-year-old Eritrean minor I meet elsewhere in northern France. She has only just been found after disappearing completely for nearly two months, sparking serious safety concerns.

After leaving Eritrea, Samira spent four months travelling through Sudan, the Sahara desert, Libya, and the Mediterranean, Help Refugees said. Hoping to reach the UK, where she has relatives in Birmingham, she arrived in Calais in July 2016.

“It was not good, I had no sleep. I was tired,” she says of her arrival in Calais at the squalid Jungle camp. When the bulldozers came in and the demolition of the camp's tents began in October, Samira was housed with other children in converted shipping containers. After an age assessment, she was told in November that she was eligible for refuge in the UK under the "Dubs amendment", a British scheme that aimed to help unaccompanied refugee children, according to Help Refugees.

But when she went to meet the bus she thought would take her to the UK, she was not allowed to board. While others climbed on, Samira was left behind, and didn’t understand why. Help Refugees says what happened is still unclear. The Home Office told BuzzFeed News it could not comment on individual cases.

Samira was then sent to an accommodation centre some three hours' drive south of Paris. There the friends she had made were resettled in the UK or elsewhere in France, but she was left waiting, and heard nothing about if or when she could join her family.

“Samira did not understand what was happening,” says Michael McHugh, Help Refugees’ child protection officer in Calais, who has been working on Samira’s case. “She was alone and waiting around. She was just waiting for a transfer date.”

Young people in these situations are tenacious and "not stupid", McHugh says: "All they want to do is get somewhere and start their life."

Samira heard that some people were still crossing to the UK from the north of France, so she left the accommodation centre and travelled to a camp 70km from Calais. There she contacted Refugee Youth Service, a charity working on the ground, and explained her vulnerable situation. It alerted the relevant authorities, as well as French state anti-trafficking teams, who considered Samira to be at risk. But when Help Refugees volunteers came to the camp to find her in January, she had vanished.

She was found six weeks later, in March, when volunteers from the Eritrean community worked to locate her in yet another camp, near Calais. She had bruises on her legs and marks on her body, and reported being in pain and feeling tired and stressed.

Samira said she had gone to Paris, believing there was a chance she could get the UK from there. She had been sleeping in a tent in the La Chapelle district with some other girls. It was there she was told by men she had never met before that she would have to “work” if she wanted to stay.

Sabriya Guivy, a legal adviser at Help Refugees, interviewed Samira when she was found. “She was looking in pain, mentally and physically, after what had happened in Paris,” Guivy says on the bumpy car journey on the way to meet Samira.

“She said she was in Calais but didn’t know why, and went to another place and didn’t know why," Guivy says. "Her patience finished and she left. But she realised what was happening was not normal for her.”

Samira eventually agreed to go under French state protection, meaning she was granted temporary asylum and could be looked after in a safe house, while Help Refugees tried to get her case reconsidered. The charity gave her a new phone and sim card to prevent her from being contacted by anyone who may have had her number previously.

"This should not happen to underage refugees in Europe,” says Guivy, who is working on 11 other cases of family reunification like Samira's.

When I meet Samira, she has learned she will finally be coming to the UK, six months after she was turned away from the bus. She beams and hugs the volunteers when we meet in a town square. She wears grey jogging pants and black ballet pumps with small ribbons on them, and her hair is in a ponytail. She takes us to a park she likes, where children play on a climbing frame. Their mothers wear hijab and chat around a picnic table.

The charity volunteers say Samira's mood has changed noticeably since she’s heard the good news. She holds her hands together, chipped pink nail polish on a few fingers, and we drink cola and eat Mars bars around a table. She is happy to see the volunteers, and excited for the next part of her story. “I just know the name 'Birmingham', I don’t ask anything else," she says. "I am happy."

She says she’s most looking forward to going to school and says she has always wanted to study geography, “to learn about people". She also talks about looking forward to gardening, a hobby she saw an Italian neighbour in Eritrea enjoy. When asked what she wants to do when she gets older, she says: “I want to help people like me.”

Before the Calais camp was demolished, it was home to "harmful levels of bacteria and appalling hygiene", according to a report. But the transient situation for many unaccompanied minors creates different problems. “While camps and settlements are cleared, the problem will keep growing until there are adequate and sufficient solutions provided for displaced people in France,” says Boyle.

“We are especially concerned about the large number of young people living in precarious conditions without a roof over their heads and with an ever present threat of police brutality and far-right groups' aggression. The basic human rights of these children are not being met."

The global number of refugee and migrant children moving alone has reached a record high, having increased nearly fivefold since 2010 to at least 300,000 in 2015-16, according to the latest figures from UNICEF. Many children face legal battles to reach countries they should be entitled to move to.

“This whole [asylum] process does grind you down," Help Refugees’ McHugh says. "Young people have a right to know [what is happening with their case]. It is the law to be able to join your family.”

He says children in Calais are calling their families in the UK, who don’t know what to do. The process is "not navigable", he says. "It’s not user-friendly."

Campaigners had hoped 3,000 children would benefit under the Dubs amendment but only 350 have been brought into Britain through it, and in March Theresa May’s government said it would end its commitment to the scheme, in a low-key announcement.

As the UK political parties launched their manifestos ahead of the general election, there was a lack of detail on how the UK will deal with the continuing refugee crisis. The Conservative manifesto reads: “Wherever possible, the government will offer asylum and refuge to people in parts of the world affected by conflict and oppression, rather than to those who have made it to Britain.” But there is nothing on unaccompanied minors – there are an estimated 90,000 unaccompanied migrant children across Europe – despite it being a hot-button issue in parliament not very long ago.

I join McHugh at the distribution warehouse in Calais, a centre shared by Help Refugees, L'Auberge des Migrants, Refugee Youth Service, Refugee Community Kitchen, and Utopia 56, which work together to provide meals, distribute clothes, bedding and hygiene items. We can’t take pictures of the entrance of the corrugated metal building, as volunteers do not want to attract attention from far-right groups.

Almost all of the asylum-seeking minors in Calais are unaccompanied, according to a report by charity Refugee Rights. As a result, much of the work McHugh does involves introducing the refugees to positive role models, for example by inviting young Oromo professionals or Eritrean students at university in Paris to speak to them. He encourages them to consider if they can seek asylum in France and get a right to a residency permit, instead of waiting to get to the UK, where they will be assessed on their 18th birthday and could possibly returned to their country of origin if they are refused leave to remain.

He’s arranged activities including a day trip to the beach for eight young women. “We left for the beach and they turned into teenagers, taking selfies, in the sea," he says.

Many of the refugee minors living in Calais have faced racism in the area. McHugh describes a day he had organised a bowling trip for the teenage boys in town. When they got there, the woman running the centre said she did not want them there. “One of the boys said, ‘We don’t want to do this any more.’” So they went to the next café, McHugh asking the owners whether everyone in the group was welcome there.

Picnic tables and board games are loaded into the back of Help Refugees’ mobile youth centre, which parks up near the distribution point on the evening we visited. It aims to make the minors less anxious, as well as to provide some activity during the day. Boxes of Connect Four are taken out and the teenagers gather around. The volunteers try to provide day-to-day social work, trying to advise the children to go under French state protection. Many are not keen, fearing it would hinder them from reaching the UK.

There’s a line queuing up for food distributed by Refugee Community Kitchen, which has a whiteboard that says it provides meals for 400 people in Calais and 150 in Dunkirk, and makes 500 distributions through Utopia56, a charity that does night-time outreach work.

The authorities tolerate distribution of food and essential supplies during this small window in the evening. After the dismantlement of the Calais camp and the fire that devastated the Grande Synthe camp in Dunkirk, it was announced there would be no more humanitarian action for refugees on the part of the state. As a result, the only way refugees can access food, clothes, showers, blankets, information, and support is through volunteer organisations.

It is cloudy when the gendarmerie get out of their vans to usher the children at the distribution point into the forest. The volunteers pack away the plastic foldable tables, the games, and the food, while the police motion to the minors to get up. Some have their hoods on, others pick up their new blankets and ponchos, and start walking in a line towards the wood, to face another night in the rain.