Both YouTube and Facebook now support 360-degree, panoramic video. Mobile device users can swing the phone about their body, examining the scene from any angle. On a desktop, a user can click and drag inside the video, swinging the field-of-view back and forth, up and down. In Google Cardboard (or a similar headset), a user can move their head naturally, looking around a scene as though their head were somehow levitating within it.

We're not used to seeing the person holding the camera in video footage, but in spherical video it's unavoidable. The New York Times video "The Displaced" avoids exposing the camera handler through careful staging and postproduction edits to remove the filmmaker's gear. We decided to include ourselves and our equipment in the final cut of our video, as we were curious how this kind of transparency can serve journalists operating on a short schedule and with minimal technical overhead. Showing reporters and equipment isn't as "polished," but editing the cameraperson and gear out of a shot to create the illusion of an autonomous camera can be deceptive. Let us know what you think!

Here’s what we learned working on the Valley fire project:

Watching 360-degree video feels a little like being inside a video. Though a user can't see their own body, the sense of a "viewpoint" is very strong. Physical sensations like vertigo are much stronger than they would be in flat video. This idea is often presented as cautionary advice to a would-be 360-degree filmmaker who doesn't want to disorient his or her audience. But it also suggests the importance of perspective in spherical video.

Ditching the Tripod

We decided to ditch the tripod for this piece. Handheld shots are less steady, but they also convey the reality of the situation being filmed. Think about a chase scene where the camera operator is holding the camera while running. The back-and-forth motion of the camera conveys the experience of running more viscerally, even if the surrounding scene is more difficult to see.

In contrast, a camera on a tripod provides a very still shot, detached from the action surrounding it. Even if a viewer is visually surrounded by action in a 360-degree video, there's a sense of detachment that detracts from the physical immersion experience, and the viewer feels like a spectator. In 360-degree video, the viewer's perspective depends on where the camera is situated. We asked Pat Hand, whom we interviewed about the loss of her home in the fire, to carry the camera and guide the viewer. We were curious about how being "held" by a subject, rather than a tripod or a camera operator, would change a viewer's experience. Would it feel more like they were standing beside her rather than anonymously observing her? Would the movement of the camera feel distracting, or add a sense of intimacy?

We, the production team, also appear in the footage. This was a deliberate decision: We think that our appearance in the video adds to the immersive qualities of 360-degree storytelling. Conventional documentary film protocol keeps the production team and the reporter out of the video frame. Everybody hides behind the camera. With 360-degree video, there is nowhere to hide. Our presence also adds an element of transparency to the project and adds to the immersive experience. We want the viewer to feel like they are there, witnessing with us, the burned ruins of Hand's house and hearing the story she has to tell.

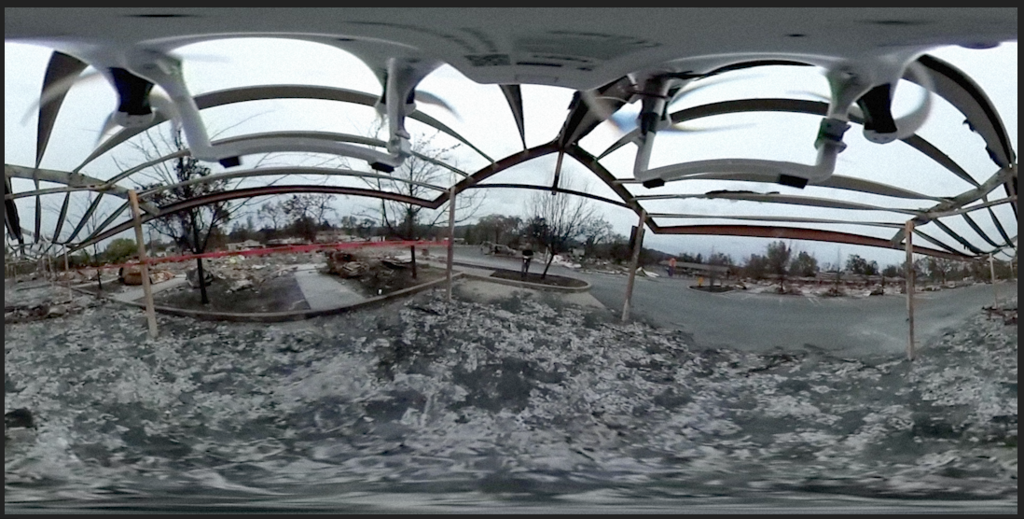

Drones can access spaces humans cannot or should not go. Toward the end of our visit, Hand stepped on a nail in the ruins of her home -- it went right through her shoe and into her foot. Hand is fine, but the area is filled with dangerous debris. Elsewhere in Anderson Springs, cleanup crews wearing hazmat suits and thick-soled boots stepped carefully as they rooted through fire debris looking for hazardous materials. Carrying a 360-degree camera, the drone captured footage that takes viewers through the remains of Hand's house, recording perspectives that would have put a human in harm's way. Drones are great at moving nimbly or hovering in place, so they can capture smooth footage.

Recording Sound

Editing in 360

Editing 360-degree video feels a little like darkroom photography — anything you see while filming is unstitched, and the editing process happens while the images are flattened out in a rectangular panorama. As an editor, you can't test the actual viewing experience without exporting the video and opening it in a specialized player. To test the video at its final resolution and in a spherical viewer, we inject spherical metadata and upload the video to Youtube or Facebook many times throughout the editing process. Compared to traditional digital video, we're editing blind. Which is pretty exciting! We stumbled across a few ideas about the form and rhythm of VR editing while we were at it.

Copy, Stack, Crop!

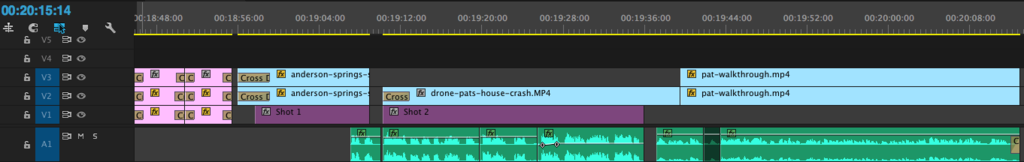

Footage captured from GoPros needs to be stitched with Autopano Video Pro and Autopano Giga. Ben has made a useful walkthrough. After this, the footage is edited in a distorted rectangular aspect ratio. Although 360 video may lack "framing" as such, but the ordering of cuts and the way one scene transitions to another provides a great deal of creative control. This is clear when you look at the stitched footage in editing software like Adobe Premiere.

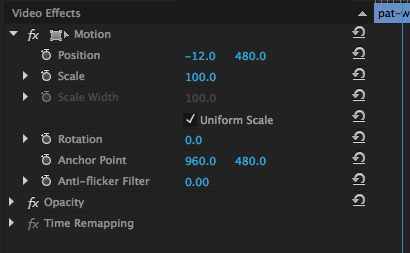

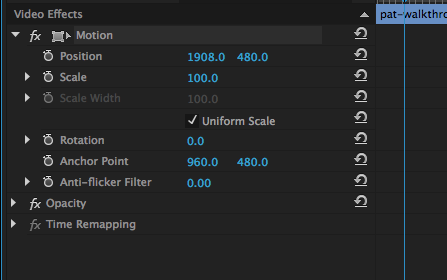

The center of the rectangular frame in editing software (after the footage has been stitched) is the "baseline" direction a viewer is facing when a video starts.

Think about the footage as a beach ball -- a shot isn't "framed," but it can be rotated so that different zones are in front of or behind the viewer at the start. To "rotate" the beach ball of a shot, copy the clip and stack it on top of its twin in the editing timeline.

Timeline View in Premiere

Doppelgänger Demo

View this video on YouTube

You can also crop shots instead of moving them off-frame to achieve the same effect. Ainsley also used this cropping approach to create a doppelgänger demo where multiple shots in the same scene are combined by cropping each clip around a moving figure.

Synchronous Shapes!

Familiar forms of movement and rhythm that help us compose framed scenes aren't gone, just expanded. Thinking about a scene in terms of its basic shapes is a useful abstraction to start seeing how cuts between scenes can have a visual cadence. For example, in the screengrabs below, the transition goes from a large, rectangular, dark shape to an empty-rectangular structure.

The orientation of the objects in each scene places the viewer in a long corridor that begins with the shed and moves through the burned building structure. Inverting expectations would also be fun to play around with. A cut from a speaking subject to a blank wall would push a viewer to whirl around, inducing a feeling of physical movement and energy before they see what is behind them.

The experience of 360 video isn't wholly transportive. Most people won't cram themselves into a Google Cardboard or other virtual reality headgear, but they will click around in a browser window or swing their phone around. We prefer creating video with a mobile device in mind, as opposed to a computer, because a user has a sense of "in front of me" and "behind me!" that feels really filtered down in the standard browser version. "Clicking" to drag the viewport around changes the experience because the user has to repeatedly make discrete decisions about where to turn the camera, interrupting (even slightly) a viewing experience. The sense of exploration and discovery is more continuous inside a headset or on a mobile device that users can explore through their movements.