LOS ANGELES — There are many things one could say to a crowd of roughly 600 of Hollywood's biggest stars and most influential executives, especially when that crowd is gathered to honor some the greatest figures in filmmaking history. For singer-actor-activist Harry Belafonte, it became an opportunity to speak truth to power.

Since 2009, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has separated its honorary Oscars from the main Academy Awards telecast. For this year's ceremony, a formal affair held Saturday night at the Ray Dolby Ballroom in Hollywood, the Academy chose to give honorary Oscars to the prolific screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière (Belle de Jour, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, The Unbearable Lightness of Being), actress Maureen O'Hara (The Quiet Man, Miracle on 34th Street, How Green Was My Valley), and acclaimed animator Hayao Miyazaki (Spirited Away, Princess Mononoke, The Wind Rises). Each were feted with heartfelt testimonials from friends and admirers. Director Philip Kaufman (The Unbearable Lightness of Being) spoke of Carrière's tireless creative energy and penchant for doodling cartoons while in the middle of heated arguments. Clint Eastwood and Liam Neeson spoke of O'Hara's uncommon beauty and talent. Fellow animator John Lasseter praised Miyazaki as "the most original filmmaker ever to work in our medium." And in turn, each of the honorees charmingly expressed their gratitude for the honor.

Harry Belafonte, however, stood apart. For one, the Academy chose to bestow a special award to him, the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award, created to honor an "individual in the motion picture industry whose humanitarian efforts have brought credit to the industry." Belafonte certainly qualifies, as one of the leading figures of the civil rights movement of the 1950s and '60s, and one of the loudest voices in show business protesting apartheid in South Africa in the 1970s and '80s. The 87-year-old Belafonte has never been shy about speaking his mind, and he didn't stop when talking with the assembled guests at the Governors Awards — many of whom were actors and filmmakers doggedly campaigning for an Oscar this year.

Belafonte first thanked Susan Sarandon for her introduction covering Belafonte's experiences (as well as for her own activism), and Chris Rock for starting off the celebration with some pointed humor. (Of Academy president Cheryl Boone Isaacs, Rock said, "It's nice to see a black president that America still likes!" Then, acknowledging the week's election results, Rock added, "Clint Eastwood had a great Tuesday. He did!")

Then Belafonte turned to his prepared remarks, and he didn't waste any time, immediately evoking the virulently racist film Birth of a Nation to speak to Hollywood's shameful past with regard to the portrayal of race. And he did not stop there.

Belafonte's remarks, published in full below, offer both a pointed and powerful rebuke of Hollywood's past and a stirring inducement to continue the industry's more recent progress on human rights issues.

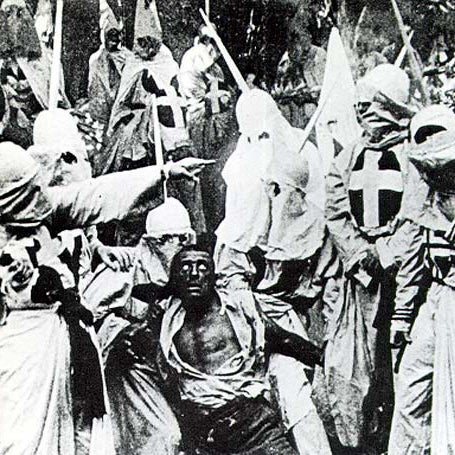

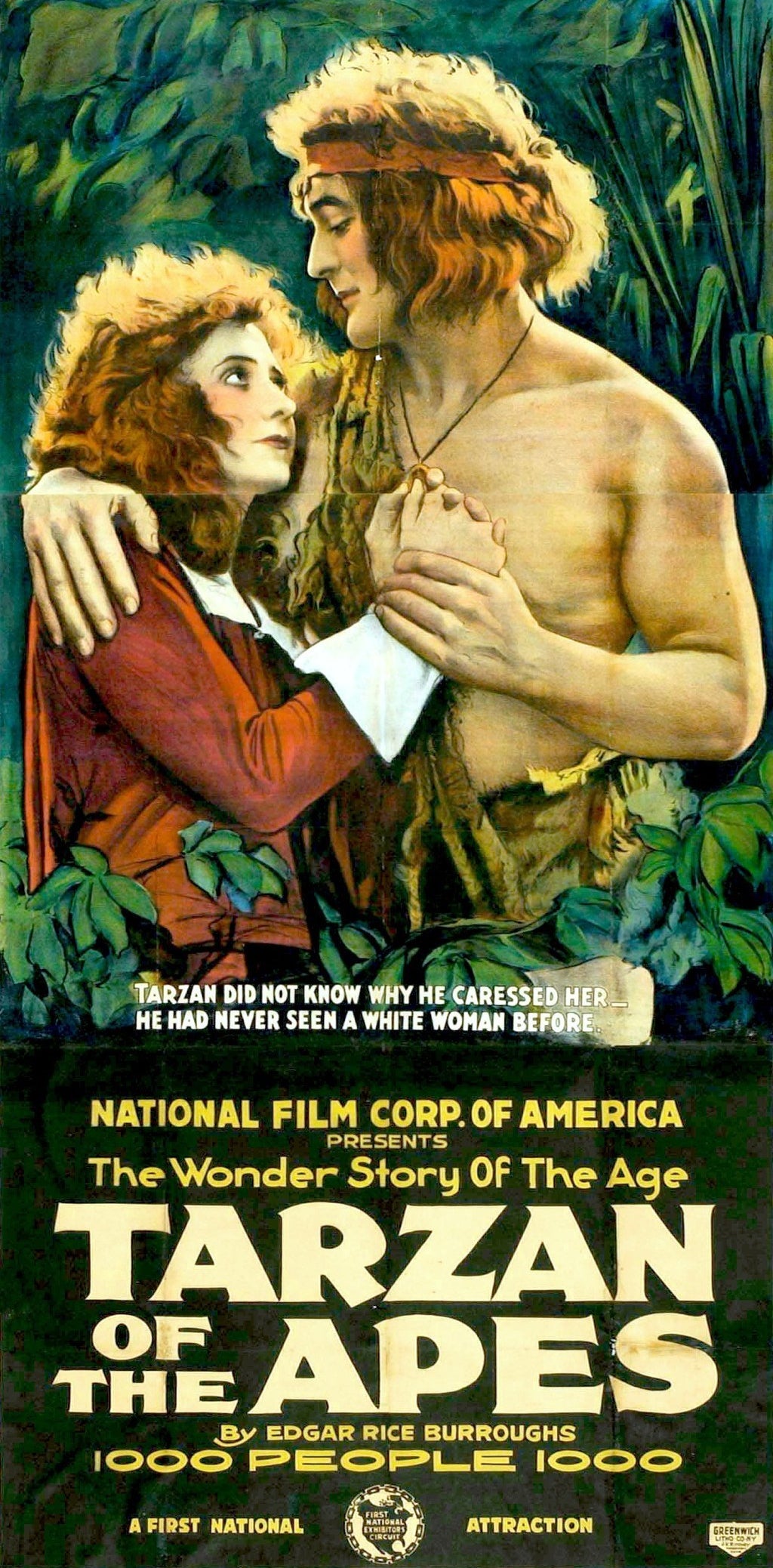

America has come a long way since Hollywood in 1915 gave the world the film Birth of a Nation. By all measure, this cinematic work was considered the greatest film ever made. The power of moving pictures to impact on human behavior was never more powerfully evidenced than when, after the release of this film, American citizens went on a murderous rampage. Races were set one against the other. Fire and violence erupted. Baseball bats and billy clubs bashed heads. Blood flowed in [the] streets of our cities, and lives were lost. The film also gained the distinction to be the first film ever screened at the White House. The then-presiding President Woodrow Wilson openly praised the film, and the power of this presidential anointing validated the film's brutality and its grossly distorted view of history. This, too, further inflamed the nation's racial divide.1935, at the age of 8, sitting in a Harlem theater, I watched in awe and wonder the incredible feats of the white superhero: Tarzan of the Apes. Tarzan was a sight to see. This porcelain Adonis, this white liberator, who could speak no language, swinging from tree to tree, saving Africa from the tragedy of destruction by a black indigenous population of inept, ignorant, void-of-any-skills population governed by ancient superstitions, with no heart for Christian charity. Through this film, the virus of racial inferiority, of never wanting to be identified with anything African, swept into the psyche of its youthful observers. And for the years that followed, Hollywood brought abundant opportunity for black children in their Harlem theaters to cheer Tarzan and boo Africans.Native Americans, our Indian brothers and sisters, fared no better. And at the moment, Arabs ain't lookin' so good.

But these encounters set other things in motion. It was an early stimulus to the beginning of my rebellion, a rebellion against injustice and human distortion and hate. How fortunate for me that the performing arts became the catalyst that fueled my desire for social change. In its pursuit, I came upon fellow artists, like the great actor and my hero, singer-humanist Paul Robeson, painter Charles White, dancer Katherine Dunham, [the] historian's superior academic mind Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois, social strategist and educator Eleanor Roosevelt, writers Langston Hughes and Maya Angelou and James Baldwin. They all inspired me. They excited me. Deeply influenced me. And they were also my moral compass. It was Robeson who said, as you heard in the film earlier, 'Artists are the gatekeepers of truth. They are civilization's radical voice.' This Robeson environment sounded like a desired place to be. And given the opportunity to dwell there has never disappointed me.For my like of activism and commitment to social change, the opposition has been fiercely punitive. Some who've controlled institutions of culture and commentary have at times used their power to not only distort truth, but to punish the truth-seekers. With interventions like McCarthyism and the blacklist, Hollywood, too, has sadly played its part in these tragic scenarios. And on occasion, I have been one of its targets.

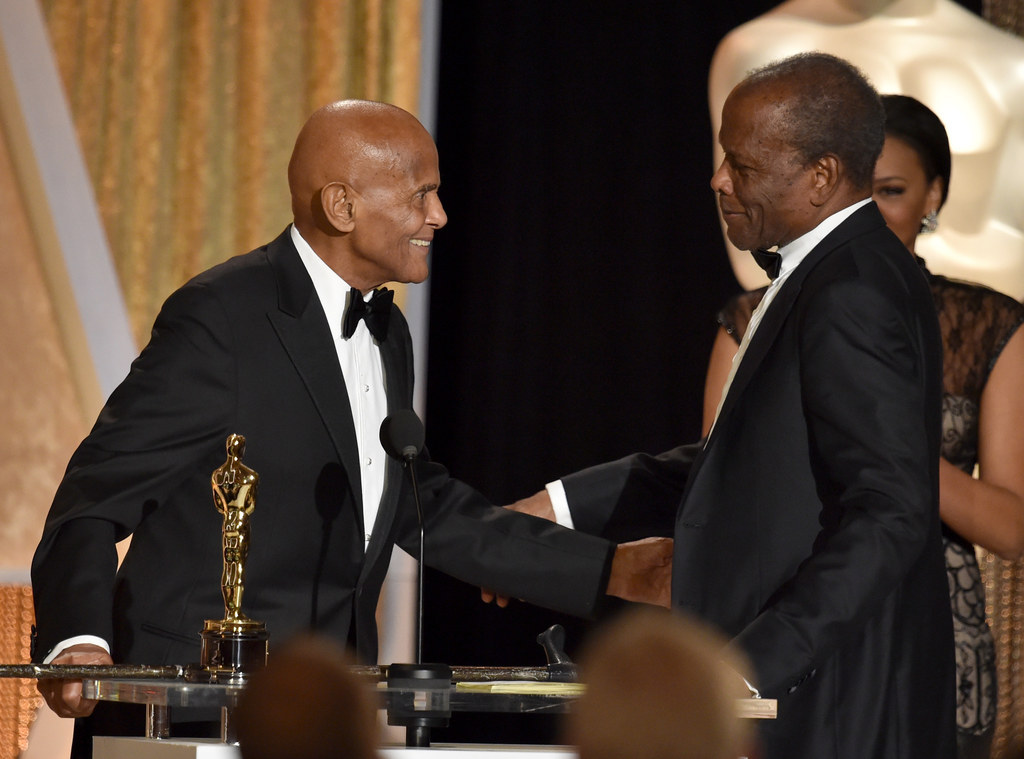

However, from the cultural environment that gave us all this social drama and all those movies — Birth of a Nation, Tarzan of the Apes, Song of the South, to name but a few — today's cultural harvest yields a sweeter fruit: Defiant Ones, Schindler's List, Brokeback Mountain, 12 Years a Slave, and many more. And all of this happening at the dawning of technological creations that would give artists boundless regions of possibilities to give us deeper insights into human existence. How fortunate for me that I have lived long enough for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to have chosen to bestow this honor upon me. Tonight is no casual encounter for me. Along with the trophy of honor, there is another layer that gives this journey this kind of wonderful Hollywood ending. To be rewarded by my peers for my work for human rights and civil rights and for peace — well, let me put this way: It powerfully mutes the enemy's thunder.Approaching 88 years of age, how truly poetic that as I joyfully glow with my fellow honorees, we should have in our midst as one of our celebrators a man who did so much in his own life to redirect the ship of racial hatred and American culture. His efforts made the journey a bit easier. Ladies and gentlemen, I refer to my friend — my elderly friend — Sidney Poitier.

I thank the Academy and its Board of Governors for this honor, for this recognition. I really wish I could be around for the rest of this century to see what Hollywood does with the rest of the century. Maybe, just maybe, it could be civilization's game changer. After all, Paul Robeson said, 'Artists are the radical voice of civilization.' Each and every one of you in this room, with your gifts and your power and your skills, could perhaps change the way in which our global humanity mistrusts itself. Perhaps we as artists and as visionaries, for what's better in the human heart and the human soul, could influence citizens everywhere in the world to see the better side of who and what we are as a species.I thank each and every one of you for this honor, and to my fellow honorees, I could have had no better company than to have shared this evening with each of you. Thank you very much.