The sour relationship between shame and women’s sexuality is nothing new. It’s the strawberries stitched on Desdemona’s handkerchief in Othello; it’s the abusive comments on Kim Kardashian’s Instagram every time she displays her body like the internet’s own Venus; and it’s every woman who “should have known better than to go out dressed like that” if she doesn’t want to attract negative attention.

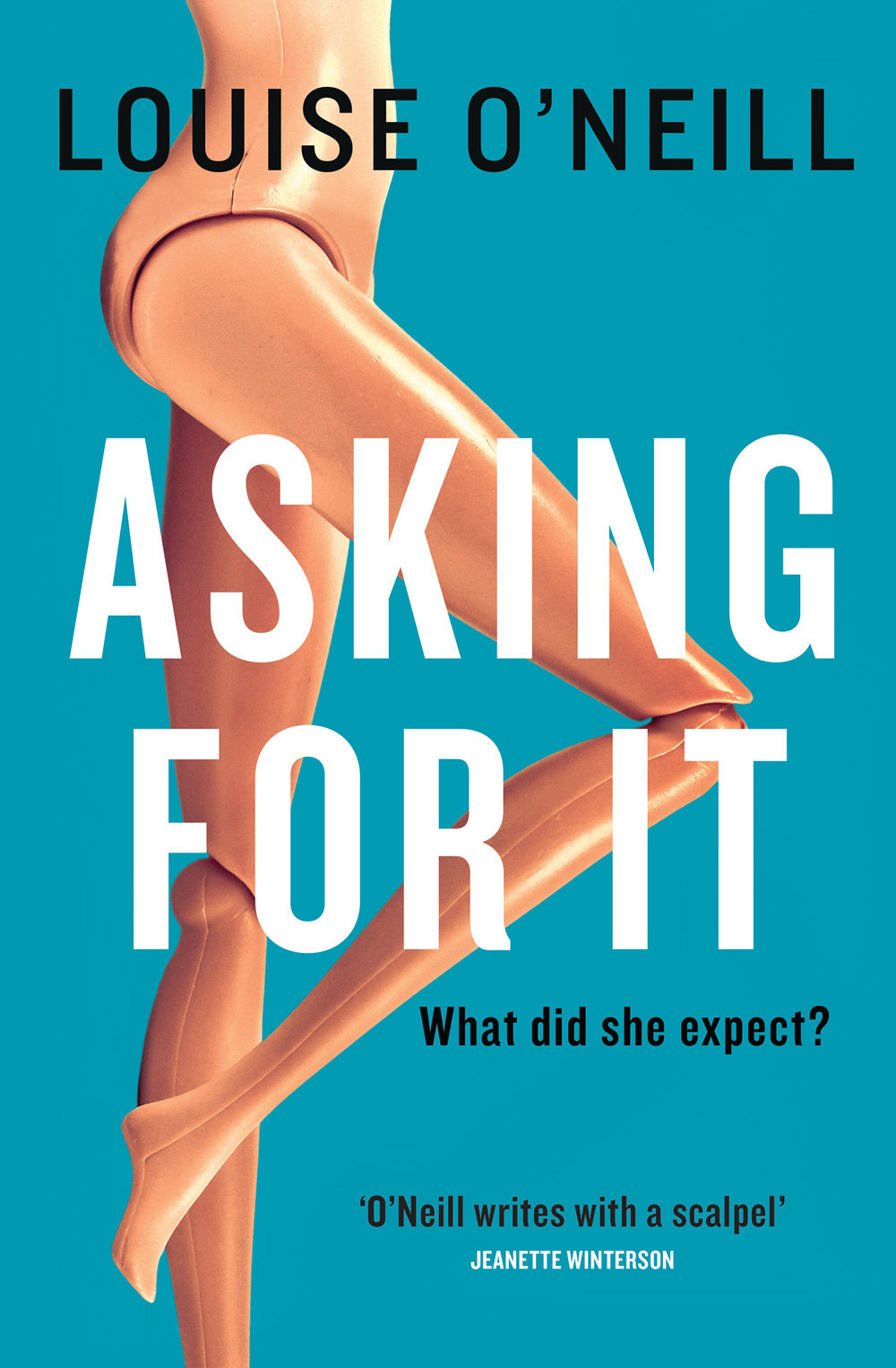

It’s also the subject of Louise O’Neill’s new novel, Asking for It, in which Emma, a popular teenager, watches her life unravel after she’s gang-raped at a party and photos of the incident go viral on Facebook. Emma was “off her face”. Emma was wearing a dress that her brother calls “a bit slutty”. Emma, says the consensus in her small Irish town, was asking for it. BuzzFeed UK spoke to the author to talk about female sexuality, consent, and the importance of unlikeable literary heroines.

Writing a novel that calls into question this albatross that women have worn for centuries was a natural choice for O’Neill. She was first truly awakened to “the idea that female sexuality is seen as a really dangerous force that needs to be controlled” while she was at uni. A gender and sexuality module at university introduced her to works involving women under fire for expressing sexuality and desire.

That year, she read old classics: Tess of the D’Urbervilles, Madame Bovary, andAnna Karenina – as well as more contemporary fiction: The Handmaid’s Tale and Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, all forming a series of profound lightbulb moments for the author. “It was one of those huge, incredible experiences where I really felt like my outlook had been intrinsically changed by the words on the page,” she says, “like it was just word after word of power.” She was also struck by the sticking power of the same sexist attitudes: “I could really see parallels between the societies depicted in these novels and the society in which we live today.”

For O’Neill, the red “A” pinned on Hester’s dress in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter is a “literal example of slut-shaming” no different from the 2013 pictures of a 17-year-old girl fellating a man at a concert in Slane, Ireland. Those images were pinned around the internet two years ago, with a litany of abusive comments attached: a viral pictorial cautionary tale of what happens to women who put a foot out of line.

The girl involved did not file a complaint and, to date, nobody has been charged for sharing the images online. Following the incident, the Irish Mirror reported that while the girl involved made a verbal complaint of “serious sexual assault”, and expressed concern that her drink was spiked to officers at the concert, an official complaint was not made, so charges were never brought. A source told the Irish Independent at the time: “The girl is getting on with her life.” Her reputation as “The Slane Girl,” however, lives on. “It’s never ‘The Slane Boy’,” O’Neill says, referring to the man receiving oral sex in the photos. “It’s always the woman who’s supposed to uphold these moral values.”

In Asking for It, when Emma overhears fellow students gossiping about the pictures of her showing “naked flesh spread across rose-coloured sheets” that her rapists post on the “Easy Emma” Facebook page, they ask, “Who does that? Who actually does shit like that?” The follow-up, “...and then lets them video it?” makes it clear that the blame is laid at Emma’s door, and not the “good boys” with “two thumbs up to the camera [and] fingers inside the body.” In the eyes of Emma’s peers, parents and, she fears, the law, it’s her own fault because she was drunk, high, and wearing a revealing dress. For the boys who sexually abused and publicly humiliated her, they were doing nothing wrong because she was “asking for it”.

On one hand, O’Neill says, social media can provide a platform for previously unheard women’s voices. “It can create a community to share stories, and connect with women who have gone through similar experiences, or just show solidarity, and that’s really powerful.”

She recalls the recent New York Magazine cover that showed 35 women allegedly sexually assaulted by American television personality Bill Cosby. Alongside them was an empty chair, which the magazine said signified “the countless other women who have been sexually assaulted, but have been unable or unwilling to come forward.” An accompanying hashtag, #TheEmptyChair, encouraged people to share their stories of sexual assault, or express their solidarity for those who had experienced it, on Twitter.

“It was just so powerful,” O’Neill says. “There’s a conversation happening that would have been brushed under the carpet 10, 15, 20 years ago, whereas now people are saying, ‘No, this is unacceptable.’”

But social media is a double-edged sword. If the imageboard 4chan allowed a man to sow the seeds of shame when he posted illegally obtained mobile phone pictures of naked celebrities, then the mass of negative reaction toward those women that ensued on social media and everywhere else, watered those seeds into a jungle of hate. “I remember in The Female Eunuch, Germaine Greer saying that women have no idea how much men hate them,” O’Neill says. “But then you look at something like Twitter and you think, well now we can see it.” She likens the scrutiny that women face on social media to the Salem witch trials. “On Twitter when people talk about these things they get abuse and death threats and screamed down as though being a woman in a public space means that you need to know your place and stay in your box,” she says.

Earlier this year The Runaways’ bass player Jackie Fuchs spoke for the first time since 1975 about her rape by the band’s manager Kim Fowey. “It’s taken me years to talk about it without shame,” she said. O’Neill recalls a similar sentiment expressed by Madonna when she told talk show host Howard Stern about choosing not to report her experiences of sexual abuse. “I remember her saying that she’d already gone through this incredibly damaging experience and that the last thing she needed was to be judged and shamed for it,” she says. “Unfortunately there’s a real element of truth in that for a lot of people who have suffered rape.”

The additional layer of “having to be harangued in front of the prosecutor and having to say, ‘Yes, I was drunk’, or ‘I was wearing a short skirt’” was something O’Neill wanted to explore in the book. “I was really interested in the girls that didn’t go ahead with bringing charges against their attackers because of [that thought].”

Just like Emma in Asking for It (who also initially denies that anything more serious than her loss of reputation has occurred), this kind of morality-gag leaves victims of sexual assault feeling alone and powerless. “There’s so much shame and violent reaction attached to women telling their stories,” O’Neill says.

The ways that victim-blaming and slut-shaming are so intertwined means that education around consent is essential in order to see a higher conviction rate, O’Neill says, “because rates of conviction in the UK and Ireland are amongst the lowest in Europe. It’s just so horrendous that the message that’s sent out is that crimes against women are not our priority.”

Rather than try to reconcile sexual assault with ourselves by considering whether or not the victim deserved it, O’Neill says that we just need to accept a simple truth: “In every circumstance rape is wrong. It doesn’t matter how wonderful the perpetrator has been up until that point, it doesn’t matter if the victim is a sex worker. It just doesn’t matter.”

To drive that point home, O’Neill says she deliberately made Emma unlikeable, like a modern-day version of Great Expectations’ Estella. By creating a girl who is vain and selfish, not least when she repeatedly dismisses the rape claims of her best friend, or stabs other girls in the back in order to get with the boys she wants, O’Neill leads her reader into the murky position of wondering whether Emma did indeed “deserve” what she got. “[It’s supposed to] make the reader question their prejudices about what a ‘perfect rape victim’ should be like,” she says.

“We think victims only deserve our sympathy if they’re well-behaved or if they’re a good student, or if they’re white or haven’t taken drugs, so I wanted the reader to really think about victim-blaming through whether they found themselves blaming Emma.”

Of course, there is a specific conclusion O’Neill hopes her readers come to. “If you didn’t give consent, if you didn’t feel comfortable, if you were forced or coerced into it, and you didn’t want to do it, then that is rape,” she says.

“There still is a huge cultural shift that needs to happen and that’s why I wrote this book. I want people to read it and have a conversation and really think about how they define rape and consent.

“I want sex to be seen as something that’s normal, healthy, and that two people can enjoy while respecting each other’s boundaries, not something that’s violent, or has to be forced by one person.”

Asking For It is on sale now.