In elementary school, it hadn't really mattered that I wasn't talking to boys and they weren't talking to me. At that age, it's almost like we all know we're pretending when we say we (well, you) are "going out" with someone. We're kidding! We're ELEVEN, for crying out loud.

In middle school, having a boyfriend is not a fucking joke. Nothing is.

Dakota Middle School looked (and looks) like a prison. There is no getting around it. There aren't any windows, the ceilings are low, and the color scheme is this one very specific shade of brown. It should have helped that, in a way, we were all starting there as "new kids"; it was there that kids from Pine Lake joined up with kids from two other local elementary schools, which should have meant there would be more people we didn't know than we did. It's just that some of those suburban kids knew each other already anyway, from their cul‑de‑sacs and their parents and their sports teams. Some of us were still newer than others.

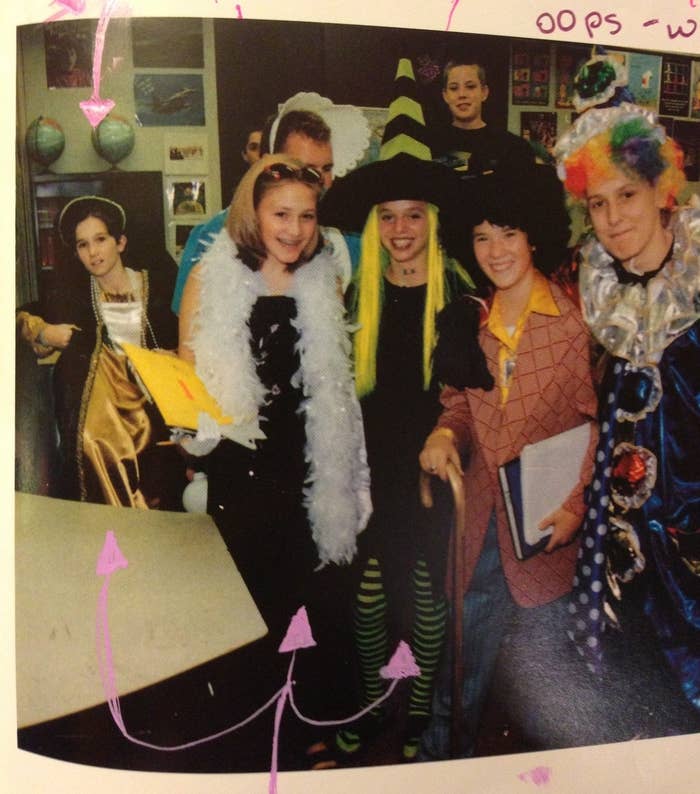

In the early part of sixth grade I was trying to make my friendship with Kelsey — the first friend I made post-Mandys, who not infrequently tried to convince me that we should "become witches" — work. I also was putting in long hours trying to make friends (defined loosely) with a few kids from the other elementary schools in the district. There was Stacy, who was essentially a human squirrel; Amanda, who was obsessed with jawbreakers and gel pens and, later, would become a cutting, mean-spirited asshole of a child; and Brynn, of whom I remember not one defining characteristic but who had the distinct advantage of being three-dimensional. Look, it's all about opportunity. I was silent, I was small, and I had translucent skin. ("I thought you were allergic to the sun" — a so‑called friend.) I had to mine whatever companionship I could from my classmates, my gym partners, and the kids on my bus. I had to find people who would, at the very least, sit with me at lunch, and who were willing to listen to me talk about my newly formed crush on a very popular and adorable boy named Chris who sat near me in Social Studies. I gave up on the idea of friends who would want to hang out with me on the weekends almost instantly. I was too scared to hang out with more than two people at a time, anyway. I figured I would be happy enough spending my free time with books, computer games, and my still somewhat-pliable younger brothers.

I would have been perfectly (mostly) fine just finding people to sit with and talk to. I would have been fine just imagining that the next year would be inexplicably and immeasurably better. (I would, after all, be turning thirteen.) There is no reason for any child to expect to be truly happy in middle school, and although it wasn't as if some of us weren't trying anyway, many of us seemed content to quietly pass the time until things got better. I could keep spending the twenty minutes between arriving at school and the start of my first class sitting in a bathroom stall because I couldn't find anyone in the hallways to talk to. It wasn't ideal, and a lot of people probably thought I had chronic diarrhea, but at least I wouldn't be seen sitting alone in class unfashionably early.

I could have just gotten through my time in that depressing, dimly lit cardboard box of a building, handily avoiding the potential and seemingly life-threatening awkwardness of dances and parties through simple non-invitation. It would have been, if not pleasant, at least easy. But then they — the adults, who meant well but knew nothing — went and forced a social life upon us. They made us put on roller skates.

First we had to do it in gym class. We watched a safety video and got a quick lesson before tying up disgusting old roller skates (the four-wheel kind) and heading out across the wooden gym floor, in lap after lap, for forty minutes. Never mind that it was no longer 1960 and all of us had Rollerblades at home — this was physical education. It was about suffering, and confusion, and lowering our already dying self-esteem.

We only skated in circles. Sometimes when the gym teachers felt that we were getting a little too good a hang of it, they'd blow a whistle and turn off the music, and everyone would have to turn around and skate in the other direction. This was allegedly done so that we worked the muscles on the other side of our bodies, but I think it was really so that the teachers could watch us try to scramble to a stop and turn around quickly enough before they restarted the music. There were always casualties. Naturally, they were never the popular kids who, in addition to having nice hair and clothes, were apparently gifted by God or physics with the natural ability to glide.

Everyone tried to skate with their friends, which created traffic issues as well as a growing and panicky sense of isolation and hopelessness. It was hard enough to find friends in that hellscape when we were standing stationary at our lockers or sitting in the cafeteria, let alone when we were all flying around the gym on wheels. It was hard to keep up because I was scrawny and had very little athletic finesse, and it was also hard to keep up because none of the people I was pretending to be friends with were actually interested in having me skate by them. So I mostly skated by myself. It was the most tragic thing ever, except for the time when a boy skate-pushed me into the wall for no apparent reason. ("He probably likes you" — an idiot.) That was even sadder.

As if this were not enough, the overlords at Dakota Middle School decided that we should put our practice to good use with enforced socializing in the form of semi-annual trips to Saints North roller rink. Everyone understood that these trips were a very big deal. Field trips are widely considered to be a marked improvement over normal school life, but, being absent of any semblance of educational purpose, trips to Saints North were, in theory, the absolute best. If you had solid friends and especially if you had a boyfriend or girlfriend, they probably were the best. For everyone else, it was jittery stress and excitement — dread and nachos and the rush of hopeful adrenaline combined.

On the trips we were granted a few hours to skate — or, mercifully, Rollerblade — under disco balls and strobe lighting, accompanied by the most important music of our time: Savage Garden, Backstreet Boys, and Brandy. We brought cash from our parents and spent it mostly on candy and on this really great, sticky-sweet rollerball lip gloss they had. Most importantly, we tried to skate with cute boys.

There were chaperones, presumably, but I do not remember ever seeing one. Perhaps they felt, mistakenly, that nothing all that bad could happen in a roller rink. For future reference: Roller-skating field trips are the middle school equivalent of a booze cruise, except that instead of alcohol we were drunk on dozens — dozens — of Pixy Stix. Everyone fought with each other and girls cried in the bathroom. Boys broke things (How do you break things on a vast expanse of empty floor? Ask a twelve-year-old boy) and leered at the popular girls. Everyone yelled the entire time. We grew accustomed to the darkness and the enclosed space and accepted it as our new home. We lived there now. Would we ever get out? We doubted it. We went into the laser-tag room, paranoid and delirious, and shot at one another. It was a little like The Lord of the Flies, but with more 98 Degrees.

At the very first sixth-grade trip to Saints North, I decided that if I was going to be forced to be social in the dark with my classmates, I might as well be on a suicide mission. I wanted to skate with Chris from Social Studies and, in doing so, cement our future together. A future in which I would be popular — not because I necessarily liked (or knew) any of the popular kids themselves, but because having such a large, built‑in group came with so many obvious perks. For one, I wouldn't have had to worry about goddamn Saints North.

In my mind, my chances with Chris that day were fair to middling. True, I was not friends with any of the popular girls, much less the boys. True, my hair was stupid. But on the other hand, we had at least spoken to each other before, in class. I had even made him laugh once or twice. I was wearing my favorite T‑shirt. He didn't have a girlfriend that week. What could go wrong? (Everything.)

Mixed in with the other hot late-nineties jams, Saints North always played two couples' songs, before the first of which they'd make an announcement that the boys should ask a special girl to skate. The second couples' song was called the "Snowball," in which the girl asked the boy, but we all knew that the Snowball was a bunch of bullshit. If you wanted it to mean anything, the asking had to be done by the boy. Snowball was only for girlfriends to ask their boyfriends to skate after they'd already skated together for the real couples' song. Frankly, it was a little unseemly in any other scenario. I don't know where we learned all these regulations or why we were all so sexist, but that is just how middle school works, and it's terrible. Everybody should sit at home from ages eleven to fourteen. People at that age are too mean and weird and dumb to be let out in public.

Because nobody talks to each other directly about anything in middle school, I planned to have Kelsey ask Chris if he'd ask me to skate during the real couples' song. He needed to ask me. (I realize now that I should have asked her to magic this event into existence using her witchcraft expertise. It could not have hurt.) This, sadly, is among the bravest things I've ever done. I don't really know what I was thinking. I must have talked myself into a now‑or‑never-type ultimatum, wherein I knew my chances in the confines of our actual school were slim to none, but my chances in a disco-lit roller rink were marginally better only because nobody knew what was going on out there on the floor. It was all hormones and chaos! I could practically just skate up alongside him and grab his hand and he'd just be thankful for the extra support, maybe. But I wasn't about to go crazy — this was a process.

I gathered my team into a huddle by the lockers. "Okay, tell me exactly what you're going to say," I told Kelsey. Stacy and I leaned closer to her, waiting for the plan. "Ummm, I'll just be like, 'Do you want to skate with Katie?' " said Kelsey. I rolled my eyes. "Oh my gosh, Kelsey, you can't be so obvious about it. You have to like, be casual." She looked confused, probably because I was making no sense. I was already starting to sweat and shake a little bit. But it was too late to turn back. "Ask him if he is asking anyone to skate for the couples' song. And then if he says no, then you can ask him if he'd ask me. Then come find me and tell me what he said," I said. I felt like I was going to throw up. I put on thirty coats of apple-flavored rollerball lip gloss really quickly to try to calm down. "Fine. That's what I'll say. Okay I'm going over there!" said Kelsey. "Wait, noooooooooooooo!" I screamed. "Too late. I'm going," she said, because middle school kids are the worst.

I ran to the bathroom and went about pretending to fix my hair, even though that damn ear-length bob was really beyond repair. I paced. When the door opened, I'd wash my hands. I had washed my hands about five times for about a billion hours total before, finally, the door opened to reveal Kelsey and Stacy and my future and my fate.

"WHAT DID HE SAY?" I stage-whispered, but I already knew. They hadn't come in the door squealing and giggling, so the news couldn't be good.

"He said he'd skate with you if you asked him for Snowball," said Kelsey, her head drooped to the side in mock empathy (middle school kids aren't capable of real empathy). "I'm sorryyyyy," she said, frowning. Then she turned around and left, presumably to get out before I could kill her.

Stacy stayed on because she was a little bit nicer than Kelsey. She sat with me on the floor while I tried not to cry. I hid in the bathroom for the rest of the field trip. I didn't want to risk the chance of going out there and seeing him skating with another girl, or seeing him laughing with his friends, or seeing him in really any situation that wasn't him confessing his love for me. Nor did I want him to see me, ever again, because then he'd have to look at me, and looking at me would almost definitely mean that he'd remember what I'd done and feel either amused or, worse, pitying. As if I weren't taking the news hard enough, I had to go and hear *NSYNC's "(God Must Have Spent) A Little More Time On You" playing through the wall. It basically felt like Justin Timberlake himself was standing over me, pointing and laughing and wearing a wallet chain.

I can clearly see now that Chris's answer wasn't as bad as it seemed that day. After all, he had expressed a willingness to skate next to me, to be linked with me publicly, if only I would ask him. Sure, he was probably just being a polite kid. But to risk upsetting the totem pole of popularity just for the sake of being friendly? That was practically unheard of. Social groups meant something. They determined who you could eat with, who you would huddle around lockers with before school, whose birthday parties you could expect to be invited to without transgressing social norms. They determined who you could go out with, and who you could reasonably ask to the school dances. They were everything.

I was groupless. I could see that even more clearly now.

I should have known better than to "go after" Chris, who, because he was popular, had his pick from dozens of girls whose temporal distance from breast development was nearly a decade shorter than mine. And it didn't matter if he thought I was nice or funny or even pretty: It was just not going to happen. I had two choices. I could move forward with my life, unconcerned by the social standing of myself and others, moving freely and proactively among cliques to form my own group of friends uninterested in emulating the cool girls or dating the cool boys. Or I could still quietly care, for a few more years, even though I'd pretend I totally didn't.

On my first day of seventh grade, in Earth Science, I was assigned to sit in a chair next to Nicole Barrett, who was blond, pretty, athletic, and tomboyish, as well as unusually popular in her own right. Nicole Barrett didn't even seem to hang out with most of the popular girls most of the time, though she certainly could whenever she wanted to. Her popularity seemed independent from that of the popular girls — she somehow made her sitting at their lunch table (her lunch table, really) seem like a favor. I don't know how to explain it. She could do whatever she wanted, and one of those things was — at times, during in‑class lab work for the most part, and in a way that made me feel like I was really helping — copying my worksheets, which I let her do because I wanted to be her friend as soon as I met her.

It isn't true that letting people copy your homework makes you popular, but it definitely doesn't hurt. This, among handfuls of invaluable, now forgotten information about rocks, is what I went on to learn in Earth Science.

On one such occasion TJ turned around in his chair and said to Nicole, "You have Grand Tetons." Then he and Mike snickered. We had, I suppose, been learning about mountain ranges recently, so the comment was not entirely without scholastic merit. He looked over at Erin and noted, "And you have Regular Tetons." They all giggled some more, and I made myself very busy filling in that day's worksheet, shifting my upper arms to cover as much of my torso as possible, writing with spindly, contracted arms the same way a Tyrannosaurus Rex might. Ignoring me, in that scenario, was really more of a favor than it was anything malicious. (Obviously, to have none of it said at all would have been the ideal, but this was middle school.) We all knew that there were only a handful of terrains and global regions with which one's chest area could be semi-accurately described, and that neither "Great Plains" nor "Arctic Tundra" were particularly flattering.

So I wasn't exactly making great inroads with TJ or Mike or Erin, but that was fine. Nicole was the one who mattered.

At first my wanting to be her friend must have had something to do with popularity, and a little of that must have had something to do, still, with Chris. It's not that anyone outside the group ever knows much about the popular kids themselves, or what they do when they hang out on the weekends (though we hear it's trouble), or even what they talk about at lunch. It's that we see a large and unshakeable network — with stars like Nicole, yes, but still a unified front — a practically infinite number of people to potentially have over after school, limitless in‑crowd dating possibilities (it always seemed like a game of Go Fish, but with people), and people to sit and stand with. That last one, actually, is really the most important. Middle school is three years spent worrying whom to sit and stand with.

If I could have had a group as big as theirs — and theirs was huge: twenty, thirty blessed children — statistics would have been in my favor, and at least a few of them would have landed in my lunch period. At least a few of them would have gotten to school when I did, and I wouldn't have had to dart to and from the bathroom in the morning. It wasn't about wanting mass approval as much as it was wishing to no longer be exhausted.

For me, and for a lot of kids, I think, the popularity myth — the idea that there's something inherently and unbreakably superior about these people — ended as soon as I realized I didn't hate them. In seventh grade, I found out they were nice and normal. Well, some of them were nice and normal. Let's not get carried away.

What happened is that I made friends with some popular girls, and absolutely nothing changed.

With Nicole it started through little notes we exchanged during class, me holding my notebook on my knee and writing something to her — about how weird our teacher was, or how boring the rocks were that day — and her carefully taking the notebook from me and writing something back. Then our friendship began to seep out of the Earth Science room and into the hallways, where we started stopping briefly to say hi when we saw each other between other classes, and even sometimes in the cafeteria. When she broke her leg playing soccer, she chose me (at least some of the time) to be the one to fulfill this weird, unwritten policy our school had in which an injured party got to leave class five minutes early, accompanied by a friend who would carry her backpack and drop her off at her next class before normal passing time made hallway traffic unmanageable. I became, for the first time of many, the skinny sidekick to a cool and collected blond bombshell — girls I'm drawn to because they're different, because they know things I don't, and because their first impulse is to create fun. Girls like Nicole essentially made me have a social life. Girls like Nicole made me less afraid of everything.

It was through our notes and our hallway walks that I learned he details about Nicole's older, eighth-grader boyfriend (something the standard popular girls only dreamed of), who was cute, wealthy, and popular, and who was on track to play varsity basketball in high school. They only kissed, she assured me, but she had sat on his lap a few times when they were hanging out after school. (This scandalized me for several days, but this is the kind of thing these girls help me with: adjusting my societal normalcy scale.) His name was Billy. Billy, as it happened, rode the same bus I did, and once it became known that I was kind of friends with his girlfriend, he started giving me obligatory little waves or half-smiles when he got on in the mornings.

Then, cruelly and out of nowhere, Billy dumped Nicole for a girl in his own grade. It doesn't matter who it was, because she was so obviously inferior to Nicole Barrett that to describe her in any way would be to give her more humanity than she deserves. Everyone could see that, except for Billy, because he was a brainless, spineless, dopey-faced idiot with poor vision and no soul. These are the things I wrote to her in class to try to make her feel better, and on some days, it worked. But Nicole stayed depressed for a while, until she became livid instead. She had been dumped while she was on crutches, which we agreed seemed pretty unfair. We went over to her house after school and ate cookie dough and talked about how stupid Billy was, how she could do so much better, and how neither of us necessarily wished that he would die, but that neither of us would be all that upset about it if it happened naturally, like in gym or something.

At some point during this early stage of recovery, Nicole started referring to Billy by the pseudonym "Nutsak," which I believe is something she learned from her older brother, and I started drawing her little stick-figure comic strips about his demise. I called them "Adventures of SuperKatie" and their plots were slight variations on this theme: My winged heroine character (SuperKatie) would witness Nutsak/Billy saying something terrible to Nicole, or being generally moronic in her presence, and I would fly in to save her, subsequently beating the shit out of him in any number of comically exaggerated ways. Nicole often helped, but it was usually me who did the heavy lifting, destruction-wise. Victory and vengeance were inevitable in six panels or less. It's not the most subtle way I've ever attempted to demonstrate my indispensability as a best friend, but anyway it made her laugh.

Nicole even showed the comics to another friend of hers, Christine (another singularly popular girl, with naturally white-blond hair and adorable button features), and that's how the two of them decided that if they were ever, in a doomsday fantasy world, to take drastic action against the bus that harbored both "Nutsak" and myself, they would make sure to get me off safely first. When they told me this in the hall one day, I felt that belonging I'd been missing since my family moved to the suburbs. Nicole and Christine and I started talking about organizing a "Crew," which was this sort of West Side Story scenario we envisioned in which she and a large group of her friends confronted Billy in the hall and threatened him into shameful retreat. That was about as fleshed out as this idea ever got, so I should have known better than to hope that Nicole meant it when she said we should all make shirts that said THE CREW on them. I also should have known better than to become so committed that I drew designs for them in my notebook.

(It has often been hard for me to know if people are serious when they talk about making T‑shirts. Just to be clear: Nobody ever means it, ever. Making and wearing matching, themed T‑shirts is embarrassing. Unless you want to make some with me right now, or something.)

It would have been nice to have that visual cue of togetherness. I imagine it would have felt like being part of one of those annoying families that wear matching family shirts when they travel to amusement parks together so they don't "get lost," but obviously inestimably cooler.

We did it without matching clothes of any kind, but Nicole and I stayed good friends through middle school, and even a little into high school. Christine and I, too. She slept over at my house and we were partners in class projects whenever we could be. She once told me her brother was possessed by a demon, and that was the second time I realized these people were not only normal (in the sense that they were abnormal, like the rest of us), but that some of them might even be seriously strange. Beautiful, but strange. Some of the others were exactly as boring as everyone else, in a way that was both a huge relief and a little depressing. A few were not very smart. Most were. A few were not very nice. Most were. All of them had great hair. (Most girls do, though, right? Girls: We're nailing it, hair-wise.) Anyway, it felt like something I should have known forever but still took thirteen (or fourteen) years to figure out: Girls are nothing to be afraid of, no matter the kind.

Boys, on the other hand.

***

Katie Heaney is a 27-year-old writer and an editor at BuzzFeed. Her writing has also appeared in Pacific Standard magazine, Outside magazine, New York Magazine, The Hairpin, The Awl, and Glamour, among other places. Never Have I Ever is her first book. You can find her on Twitter at @KTHeaney. She lives in New York City.