Until this week, I had never seen the televised version of the 52nd Academy Awards, broadcast on Monday, April 14, 1980. I didn't watch it at the time because I was in the audience: My father, who had passed away a year and a half before, was nominated for his work on the movie All That Jazz, and I went to the ceremony, as a 10-year-old, with my mother. As for why it never occurred to me to go watch them until now, I'm not quite sure: For years after my father's death, and for most of my adult life, I had a fairly active aversion to thinking about his career.

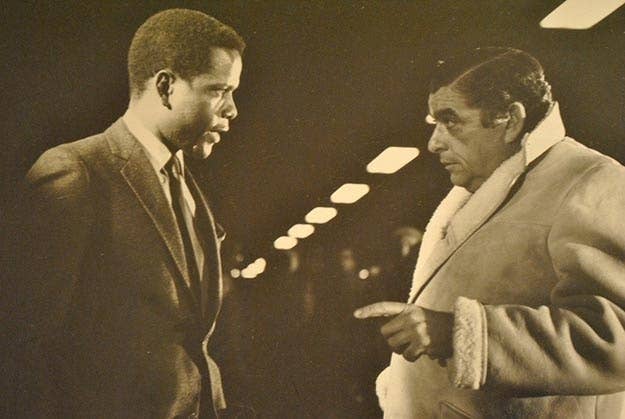

Robert Alan Aurthur — Bob to anyone who knew him — was a successful working writer, but if people remember his name now, it's because they're, well, geeks. He was a significant Golden Age of Television writer/producer (Mister Peepers, The Philco Television Playhouse, NBC Sunday Showcase); wrote a few Broadway plays (including, as one theater-expert friend often reminds me, an infamous musical flop, Kwamina); and worked on some Sidney Poitier movies (but none of the ones you've seen: He wrote Edge of the City and For Love of Ivy, and wrote and directed The Lost Man). He wrote a 1966 movie called Grand Prix, starring James Garner and directed by John Frankenheimer, that both film nerds and racing fans love and still fixate on because it was filmed in Super Panavision 70 using 65mm Cinerama cameras. (I don't know what that means; apparently, it was revolutionary.) He sometimes worked as an executive at United Artists and Talent Associates, forces in television in the 1950s and '60s; the pictures of him and his friends from then look very Mad Men.

All of that happened before I was born. When I was a kid, growing up with him and my mom, Jane, a former TV producer, in East Hampton, New York, he had a column in Esquire. He worked on a TV movie about the Attica Prison riots that ended up never being made. He wrote a screenplay called Ending about a man who was dying. And then, after beginning to work with his friend Bob Fosse, the director and choreographer who wanted to do a similar project after facing his own near-death from a heart attack, Ending transformed into All That Jazz, an account of Fosse's struggles with work, his family, and his many women, leading up to his having open heart surgery. Fosse had survived, clearly, but the Fosse character would die at the end of the movie. Before that, there would be lots of singing and dancing.

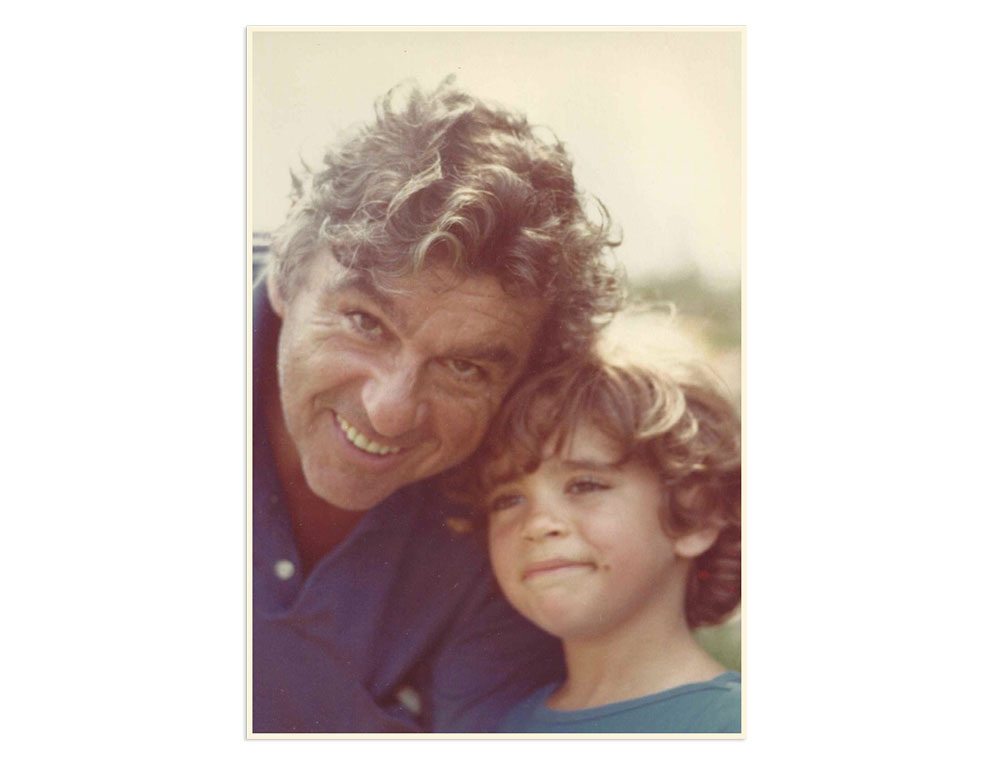

My father was wonderful to me — loving, loyal, hilarious, and outspoken — and being a writer, he was home a ton. He taught me how to drive a motorboat (so he could water-ski, yikes), how to throw a tantrum, how to be on time, how to have a lot of friends and love them, and that it was a good thing to be the only girl on a sports team.

I would go into his attic office sometimes for general, Harriet the Spy–like snooping and end up reading printed-out drafts of different iterations of the All That Jazz script. Being 7 or so, I had absolutely no idea what I was reading — plus, there were dirty parts. I did get excited that there was someone named Kate (the Ann Reinking character). And I remember that of all the confusing things, I was most flummoxed by the angel of death character, Angelique, who was played by Jessica Lange. Critics would later agree.

For years, my father smoked five — that is five — packs of cigarettes a day. He was diagnosed with lung cancer in the late summer of 1978, just when All That Jazz was about to start filming. We'd moved to New York City so he could work on its production, but he was too flattened by illness to do so. He was dead by Thanksgiving, on Nov. 20, 1978. He was 56; I was 9. Obviously, he never saw the finished film.

All That Jazz was released on Dec. 20, 1979, 13 months after my dad's death. It got some raves, but there was certainly criticism of the movie, mostly directed at Fosse for his well-known narcissism; Variety called it "self-important" and "egomaniacal." Roy Scheider's portrayal of the Fosse character, Joe Gideon, was widely praised, though — the tough-guy actor, best known for Jaws, had lightened his dark hair and learned to dance for the part. (Scheider stepped in after Richard Dreyfuss — a big star with a huge drug problem — had walked off during pre-production, sending Fosse, my father, and everyone else working on the movie into a rage and All That Jazz into a delay.)

Despite being divisive, All That Jazz was an Oscar favorite. Or at least that was my mother's take — that the movie would get a lot of nominations — and she was pretty much always right about everything. It was no surprise, then, when my father got two nominations, one with Fosse for the screenplay and the other for Best Picture as its producer. Awards season then wasn't the parade of campaigning and madness that it is now. We went to all of one pre-Oscars event: a lunch at Tavern on the Green for the New York–based nominees. I spent the entire time lurking near Justin Henry, the Kramer vs. Kramer kid, who had been nominated for Best Supporting Actor. I thought being the only children there that we might become friends, but he did not give me the time of day.

If my mother grieved over things like going to the Oscars with me instead of my dad, she didn't reveal it. She treated it like a once-in-a-lifetime adventure for the two of us. She was so strong for me then; I now realize how hard it was for her. She had lost the love of her life. I never saw her cry once. I would ask her if she cried, and she would always say yes, of course. But I think she felt like if she fell apart visibly, I would be even more wrecked. As usual, she was right.

And going to the Oscars was pretty great.

The movie got nine nominations in total. But if you remember anything about the winners of the 52nd Academy Awards, what you remember is Kramer vs. Kramer walking away with every damn thing: Best Picture, Best Actor (Dustin Hoffman), Best Director (Robert Benton), Best Supporting Actress (Meryl Streep), and Best Adapted Screenplay (Benton). In the category in which my dad's work stood the best chance — Best Original Screenplay, because Kramer vs. Kramer was not in it — Steve Tesich won for Breaking Away.

I have opinions about these wins (and All That Jazz's losses) that I can't separate from my proud and personal (and petty) feelings. So I will leave it at that.

My mother was very clear with me that we weren't winning a thing when we set off for Los Angeles — my first time there — to stay at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel for a weekend of Oscars festivities leading up to the show itself. She said Kramer vs. Kramer would win all the big awards and correctly called Breaking Away's screenplay victory. She said All That Jazz would (deservedly) win a slew of the less prominent awards, which it did: art direction, costume design, editing, and score.

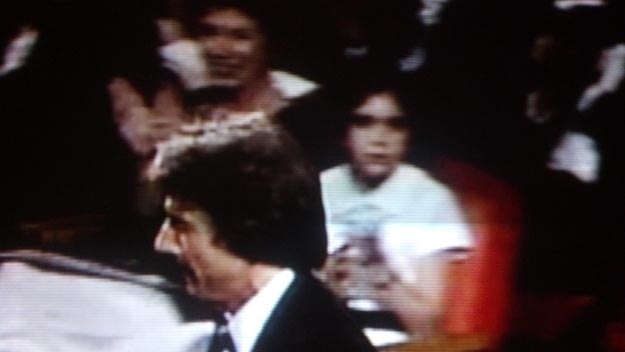

I still had my fantasies, though. I pictured marching up to the podium with Fosse and my mother after our surprise victory, and perhaps uttering a few moving sentences about my late father. (Thank god we didn't win.) My hopes did not dissipate when my mother and I were escorted to our seats at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. We were seated in the front row, and I was on the center aisle, only feet from the stage. The person with my equivalent place on the other aisle was Mickey Rooney, who was experiencing a career resurgence at age 59, and was nominated for Best Supporting Actor for The Black Stallion. My mother, perhaps seized by nostalgia, uncharacteristically made me go up to him and say hello; he was very nice.

That said, watching the show for the first time, which I recently did at the Academy's Archive in Hollywood, was more fascinating from a how-things-have-changed perspective than a mind-blowing personal catharsis. The ceremony had been broadcast — first on radio, then on television beginning in 1953 — since 1930, the second year of its existence, but in 1980, the Academy Awards still had one foot in old Hollywood: Douglas Fairbanks Jr. presents a humanitarian award, and Donald O'Connor presides over a big tribute to dance in film. As for red carpet, the announcer at the beginning says the audience will be seeing a night of the "screen's most glamorous figures" — and then the camera shows Marsha Mason and Neil Simon getting out of a limousine.

The program also still served so much more of an industry function than it does now, and that means a lot of people not used to being on television take up a good portion of the show, which is bizarre and interesting to watch. The then-Academy president, screenwriter/producer Fay Kanin, is the first person on stage. She talks about the wonder of movies and the Academy; it is Kanin who then introduces Johnny Carson, the host. (There is no opening number.) The industry-over-celebrity convention doesn't end there. A young (and so great-looking) Richard Gere does a protracted presentation of an Oscar to a guy named Mark Serrurier for his family's invention and continued innovation of Moviola editing equipment. Later in the broadcast, a producer, Walter Mirisch, gives an executive, Hal Elias, a special Oscar for his service to the Academy. That last segment is so pedantic that Carson says afterward, "Thank you, Walter. Good to see you're still that wild and crazy guy."

Carson, of course, is a host unparalleled in the brilliance of breeziness. His topical opening monologue doesn't strike me as so different from his nightly ones on The Tonight Show. Riding an anti–National Enquirer wave from that time (Carol Burnett was several years into her highly publicized battle against the tabloid), Carson calls it "the Pinto of newspapers," referring to the Ford model that had been recalled because it would catch on fire. He makes a Jerry Brown joke; he makes an Anwar Sadat joke. When mentioning how many countries the program is airing in, Carson says people are watching it in "the Arab states of Syria, Lebanon, and Beverly Hills." He talks about the theme of divorce in contemporary movies, and then adds, "It says something about our time when the only lasting relationship was in La Cage Aux Folles. Who says they're not writing good feminine roles anymore?" It's terrific. Is there not one human being on Earth today who could be a host like Carson? We need to get it together as a species.

My own memories of the particulars of the evening were scattered, but seeing the show now, they were pretty accurate. As a 10-year-old, the highlight of my night, naturally, was Miss Piggy and Carson's extended introduction of Kermit singing "The Rainbow Connection," which was nominated for Best Song. Piggy rants about not being nominated for Best Actress ("It's because I'm a pig!"); states that songwriter Paul Williams is boycotting on her behalf, and then when Carson points him out in the audience, says, "Et tu, Williams?"; and calls Carson "Jonathan" throughout.

There were a few famous acceptance speeches that night. Sally Field's first Best Actress win — not the "you like me, right now, you like me!" craziness for 1984's Places in the Heart, but the sweet, earnest one for Norma Rae — and Dustin Hoffman's for Kramer, which begins with "I'd like to thank my parents for not practicing birth control" and then runs through his conflicted feelings about acting awards. He is unsparing in his criticism, saying, "I refuse to believe that I beat Jack Lemmon, that I beat Al Pacino, that I beat Peter Sellers. I refuse to believe that Robert Duvall lost. We are part of an artistic family." He gets loud, sustained applause for it. I don't know that anyone would dare do that now from the Oscars podium.

(One addendum: Hoffman might not think Duvall lost, but I'm pretty sure that Duvall, nominated for Apocalypse Now, did. He was sitting behind my mother and me, and as soon as Melvyn Douglas won Best Supporting Actor, he left.)

I always remembered that William Shatner did something that indicated he might be a jerk. And yes, indeed he does. He and Persis Khambatta of Star Trek: The Motion Picture present the Best Documentary Oscar to director Ira Wohl for Best Boy, about his mentally challenged cousin. After Wohl gives a moving speech thanking his cousin, among others, Shatner says, "I'm glad he didn't have a larger family."

Similarly revealing, but more directly affecting our group, was Richard Dreyfuss' behavior during his presentation of the Best Actress award. At the time, my mother swore that he did a little dance step as he walked out to the podium to taunt Fosse; I will confess I didn't notice that when I rewatched it. But if you think annoying look-at-me theatrics at awards shows are a recent development — Anne Hathaway haters, take note — you should watch Dreyfuss. My mother pronounced him "high on drugs." (Dreyfuss has spoken openly about his problems with addiction during the late '70s and '80s. I contacted his representative to alert her to this characterization. And I should also mention that I've been a fan of his since I first saw Jaws, and still am — but in the spirit of honesty, I also always have thought he caused trouble for my dad, and therefore have held this grudge! Privately, until now.)

Even though Carson compares the show's length to the ongoing Iranian hostage crisis ("For those of you just joining us from home, this is day 164 of the Oscar telecast," he says toward the end. "America has not forgotten you, and President Carter is working on a plan for your release."), it was over in slightly less than three hours. We may have all known that All That Jazz would get stomped by Kramer vs. Kramer, but it was still a less boisterous contingent leaving than it had been arriving. We went to the Governor's Ball, and Bette Midler, who had been nominated for her transcendent performance in The Rose, was seated next to me, the poor thing. We discussed the entrée options. I didn't realize at the time that being stuck sitting next to a 10-year-old might suck. Luckily, she was lovely.

You would think going home would have been a letdown. For five days, I had been ferried from place to place by limo, surrounded by huge movie stars. But it was a relief. I had been obsessed with All That Jazz's fortunes. I thought ill of critics who gave it negative reviews. We would get Variety and I'd stare at its box-office grosses. I overheard gossip about which actors were nightmares and which directors were drug addicts, and vice versa.

The Wednesday after the Oscars, I went back to school. I saw my friends in the schoolyard — the same one, ironically, where Kramer vs. Kramer had filmed — and told them about my trip as we headed into our fifth-grade classroom. None of them had watched the show. But they were all really excited to hear about Miss Piggy.