The suburbs of Chicago are a 10-minute drive from the city, or one stop on the yellow-line train that runs to “The World’s Largest Village.” From the lines that separate Chicago’s northernmost neighborhood of Rogers Park, where my mother’s family moved when they made enough money, you’re only five miles away from Skokie, where I was born. They didn't get too far into the suburbs, but the city felt like it was a world away.

Follow the trees as they multiply with each passing block north, and you’re in Evanston, a town once so influenced by its Methodist founders that it came to be known as “Heavenston," as well as one of the four American towns claiming to be the the birthplace of the ice cream sundae.

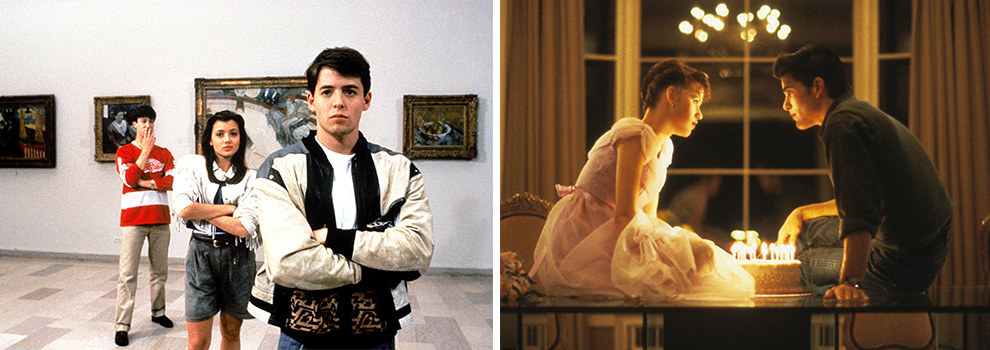

The part of the Chicagoland area known as the North Shore is what John Hughes turned into the fictional Shermer, Ill., 25 years ago with the release of the first of what is called his “teen trilogy” of films: Sixteen Candles (1984), The Breakfast Club (1985), and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986). These represent the peak of a decade filled with directorial and screenwriting credits for Hughes that, put together, represent one of the strongest bodies of work in such a short time by anybody in movies, but more importantly, present a fully realized portrait of an idyllic America seen through the eyes of its youth.

Hughes, who died five years ago this month, made the suburbs seem, if not cool, at least honest. His landscapes were skillful facsimiles, noticeable to anybody who actually grew up in the type of town where the houses look the same, the lawns are kept nice and trim by some local kid getting paid $20 a job, the high school quarterback or wrestling captain is considered a walking god, and the slightest social miscue can feel like a soap opera. Hughes set himself apart by elevating the stories of a handful of normal American teens and making them unforgettable, relatable, and sometimes even deeply philosophical, without ever being cynical.

So I too hail from Shermer, a composite of the North Shore neighborhoods where Hughes grew up and lived in as an adult. I went to school in Shermer, and I saw my family fall apart in Shermer.

Yet my Shermer — Skokie, with its abnormally high population of Jewish and Eastern European immigrants — was, for all the recognizable snobby-jock tropes, not quite the Waspy, all-American haven Hughes usually portrayed. Still, I could always use his version as the beacon to lead me home. I was a normal kid, at a normal school, trying to meet a nice girlfriend, and my parents sat down for dinner every night at a big oak table with us kids and the family dog just cute as a button begging for scraps as we laughed and talked about our day. It always felt like that’s what families in Shermer were supposed to do, because despite some kinks here and there, Shermer looked as close to normal as I could imagine.

My parents split up around my third birthday. Although I’m not totally sure of the exact reasons, the sheer amount of screams, doors being ripped off hinges, my mother's cries, my father's cries, things being thrown, and my first taste of somebody lying to me by telling me that everything would be fine all probably had something to do with it. Up until then, my memory is foggy; I remember watching Michael Jackson on MTV, getting my first Chicago Cubs hat, and loving my house with the nice lawn and the weeping willow tree outside of it. Those moments I captured, or, for all I know, maybe made up, are the closest I ever came to a Hughesian childhood.

After the separation, my parents were always busy with work or trying to have some semblance of a life, so I had a lot of babysitters. Sometimes it was my grandparents, and other times it was a neighbor, usually the high school girl next door. She pretty much left me up to my own devices, sitting me in front of a television while she chatted on the phone for hours. I’d pretend to pay attention to the movie, but really, I was fascinated by her conversations, hearing her talk about how so-and-so kissed so-and-so, and how this person was saying something about that person. I was a child, but the language of teenagers fascinated me. I would mimic the way my babysitter talked, trying to use the slang words I heard her use, all an attempt to carve out some sort of identity of my own. So when she picked a movie, Sixteen Candles, off the shelf from the local drugstore that doubled as a video rental place, I didn’t protest, even though I was more interested in the cartoons section.

I tried to act like I understood what was going on. The film made me laugh even though I didn’t get all of the jokes; it gave me my first crush (Molly Ringwald, of course); Jake Ryan was the Übermensch in my eyes (still is), the guy I wanted to look and act like when I got older; but most importantly, it looked familiar because it was literally filmed a few miles down the road from where I was sitting. I could literally walk outside of my house and be in a better place. It made coming up with my dreams and ideas of what I wanted to be like a lot easier.

My mother eventually got full custody of me, cutting off all communication with my father. The fighting between us started and only got worse. When I turned 16, my mother told me she was moving far away and said I could go with if I wanted, but she’d rather I didn’t. I was on my own with very few options, finding friends whose parents would let me crash on the couch or in the spare room in the basement every other week or so, all while trying to maintain a decent GPA, sometimes feeling like the only thing that kept me from giving up and turning myself over to Child Protective Services was thinking that if Kevin McAllister could spend one Christmas alone at the age of 8, then I could certainly finish out high school uneventfully on a friend’s futon. After that, I just wanted to get out. I wanted to get out of the suburbs; I wanted to get the hell out of Shermer.

When put together, Hughes’ individual movies open up into one big narrative. His idea for all of his films was “a town where everything happened,” as he told Premiere in 1999. “Everybody, in all of my movies, is from Shermer, Illinois. Del Griffith from Planes, Trains & Automobiles lives two doors down from John Bender. Ferris Bueller knew Samantha Baker from Sixteen Candles. For 15 years I've written my Shermer stories in prose, collecting its history.”

In his mind, there was the nice part of town with the big houses and the nicely kept lawns, then there’s the other side of the tracks where Ringwald’s Andie Walsh wants Andrew McCarthy's Blane McDonough to drop her off in Pretty in Pink, the same side of the tracks where Hughes envisioned The Breakfast Club's Bender and Charlie Sheen’s nameless character in Ferris Bueller lived and hung out. Whether or not they made it out of Shermer, we’ll never know. I didn’t come from that side, but I ended up feeling more like a Bender than a Ferris Bueller.

This world was vivid and evocatively portrayed for me and for a generation of other young latchkey kids, misfits and weirdos raised by television and movies. Yet Hughes still doesn’t get his due as a Great American Filmmaker. Bringing up his name in a conversation about Orson Welles or Stanley Kubrick will earn you stares of bewilderment, and although Molly Ringwald, arguably his muse, said, “John was my Truffaut,” trying to find a so-called auteur in the vein of Hughes as a director might prove difficult.

He could write funny, tender, often poignant screenplays in days (he wrote the script for Ferris Bueller in a week), yet he doesn’t always get the respect he deserves as one of the truly great writers — perhaps simply because his movies are largely comedies, and comedies about teenagers at that. But if there’s ever been a time for people to pay Hughes and his work the respect it deserves, it's now. The way his films have matured over the last 25 years is testament to that, and the insights he had were before their time.

“One of the great wonders of that age is that your emotions are so open and raw,” he said about why teens were such a great subject to focus on. “At that age, it often feels just as good to feel bad as it does to feel good.” The late-1970s and early-1980s default for coming-of-age teen films was films like Porky’s and Meatballs, which relied on dick jokes and gratuitous boob shots, treating high school students (mostly boys) like sex-crazed morons. Not that high school boys aren’t sex-crazed morons, but Hughes knew that there was more that could be explored, that the strange and complex fears and feelings of teenagers had rarely been put under a microscope in a way that was funny and entertaining, but also real.

Literature, from The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger (the writer to whom Hughes most often gets compared) to Maya Angelou’s autobiography, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, explored the teenage condition during the '50s and '60s. Books that tackled topics once commonly thought of as “difficult” to talk about, geared directly toward teens and younger people, were finally hitting bookshelves. What we commonly refer to as young-adult fiction today, from Judy Blume’s Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret to Nancy Garden’s 1982 novel about two girls who fall in love with each other, Annie on My Mind, laid the groundwork for Hughes to sell the idea of teens and their stories to a mass audience.

And that’s the thing that really got me: Although he’s thought of first as a director, in the more than 35 movies in his filmography, he was only behind the camera for eight. Hughes was a writer before everything else, and for a brief time, he was the best YA writer of his time. As I started to escape into books, that resonated with me.

In turn, Hughes’ work serves as the bridge between the type of YA stories from the 1970s and 1980s and contemporary writers who create books about teens, targeted and marketed specifically for teens (but who have legions of adult fans) like John Green or Rainbow Rowell, and even books that feature teenage protagonists, but might be geared toward people a little older. There’s a little of Hughes in the awkward position the title character in Ariel Schrag’s Adam puts himself in, letting a queer girl believe that he’s a trans guy so she’ll fall in love with him.

And on film, just look at the socially awkward ensemble that populates many of Judd Apatow’s movies; the Tina Fey-penned Mean Girls, set in Evanston, is almost a tribute to Hughes. Rewatching his films today, his influence becomes easier and easier to spot.

Teens have always been a mystery to adults — I know I was. I started to pull away from people early in my teens, trying to keep my head down so I could just get the hell out of high school and away from all the problems at home and all the kids in high school. I often find myself wondering how I could fit myself into one of his stories, and while my teenage years might not differ radically from the next person’s, I can’t come up with anything.

Hughes’ characters come from mostly from upper-middle-class families, the schools seem pretty good, and, for the most part, his films are almost totally devoid of people of color, something that, as evidenced by the reaction to Lena Dunham’s Girls, for instance, would hardly fly today. It’s the thing that feels the most outdated about his work, yet is a pretty dead-on portrayal of what the real North Shore was like when Hughes was bringing it to the screen. The lack of Jewish characters always felt a bit cold (although the Bueller siblings were played by Matthew Broderick and Jennifer Grey, both Jews).

There is a noticeable difference between the films Hughes directed and the ones he didn’t: The ones he was behind the camera for were always filmed in the Chicagoland area. Hughes directed the teen trilogy, Weird Science (1985), Planes, Trains and Automobiles (1987), She’s Having a Baby (1988), and Uncle Buck (1989), and if you look close enough, they just look more natural because that’s the area he wrote for. The mostly flat wooded areas, the gray skies that seem all too common for most of the year, and even the nods to the local area sports teams make the films Hughes directed stand out.

As David Kamp wrote in his 2010 Vanity Fair piece on Hughes’ time in Los Angeles in the 1980s, “Hughes simply never took to L.A. His sojourn there, though it coincided with what was arguably his artistic peak, sowed the seeds for his post-filmmaking life.” You take the guy out of Chicago, and he just wants to go back. As Kamp pointed out, “It made him realize what he did and didn’t value. He had no capacity or tolerance for industry schmoozing, no interest in keeping up with his young actors’ emerging Brat Pack party circuit.”

The movies Hughes directed are more personal and have little touches scattered throughout that make Shermer seem like a real Chicago suburb, from the Chicago White Sox hat in the principal’s office in The Breakfast Club to Cameron’s mid-century modern home set in the middle of a wooded Highland Park ravine like a Julius Shulman photo; Hughes knew how to make his movies look like the suburbs: He would simply film them there, on his home turf. That’s what made him the great Chicago filmmaker.

The real neighborhoods of the North Shore — Winnetka, Highland Park, Lake Forest, Glencoe, etc. — all just blend together into one Hughes movie in my mind. I can show you where the Home Alone house is, where the members of the Breakfast Club spent a Saturday detention together, where Cameron Frye’s glass house is, the high school used in the opening shots of Sixteen Candles, and even where Hughes himself once lived (currently for sale), right down the road from where I grew up playing hockey. These are the places where Hughes felt he needed his films to be made and to take place, and often it’s easier for me to think of where I grew up through Hughes and his films than for me to go actually go back there and revisit my own ghosts.

I sometimes think about how there’s a chance, since Hughes never stopped filling up notebooks with stories and ideas up until his death, that there might be something about a Shermer kid who ended up moving to New York, taking the train every day, trying to navigate adulthood in the big city, and missing his youth.

You watch a Hughes film, and things may turn out right in the end of the film, but he always lets you know that things will change, people will move on, and the good times can’t last forever. Jake Ryan and Sam kiss over a birthday cake, but Jake is a senior and Sam’s a sophomore; you know that Jake will end up the big man on some East Coast campus zooming around in his red Porsche. Getting home on time every night to make sure he gets to call his 16-year-old girlfriend back home isn’t likely. Ferris Bueller lays out what he thinks will happen to him, Sloane, and Cameron after the school year is over pretty clearly; and nobody really believes that John Candy’s son in The Great Outdoors, is going to be able to make it work with the small-town girl he woos.

Because no matter how great prom was, how wonderful the birthday ended up being, or even that the house was protected and Christmas could resume, Hughes always let you know that things will change. He was a gifted enough writer that he could leave you thinking, even after the credits rolled, about simple truths like that life can’t remain perfect forever, and that all you can do is enjoy the moment.

Just think of all the times you've seen Ferris Bueller's mantra “Life moves pretty fast. If you don't stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it." His movies had this rare ability to get you to laugh and feel things, but also got serious about some of the big mysteries of life without turning into Ingmar Bergman films. There are awkward moments we’ve all been in, from walking into parties we obviously weren’t invited to, to our crush unexpectedly walking into the place where we work. Seeing those moments turned into a story on film can be cathartic.

Hughes is still on my mind a lot. I once tried and failed to write his biography. When you feel such a personal connection and become as familiar with a body a work as the way I’ve gotten with his, you run the risk of looking at it less critically; you start to see what you want. I think, in some way or another, I’ve always done that, anyway. Whether it was thinking high school would be just like Sixteen Candles, the slim chance that I was going to look like Jake Ryan, or that I could at least pull off dancing to Otis Redding like Duckie in Pretty in Pink, personally, watching any of Hughes’ films once gave me an idea of what I thought me and my life should be like. Now I know better — I know that the perfect town doesn’t exist, there is no family without problems, and I definitely don’t look like Jake Ryan. High school sucked, I was a teenage mess who took a really long time to clean up.

My Hughesian life never quite panned out, but isn’t that the very definition of being a teenager? It is a liminal state of development that is temporally finite, cut short by the onslaught of responsibility and exhilaration of adulthood. Nobody can stay in Shermer forever.