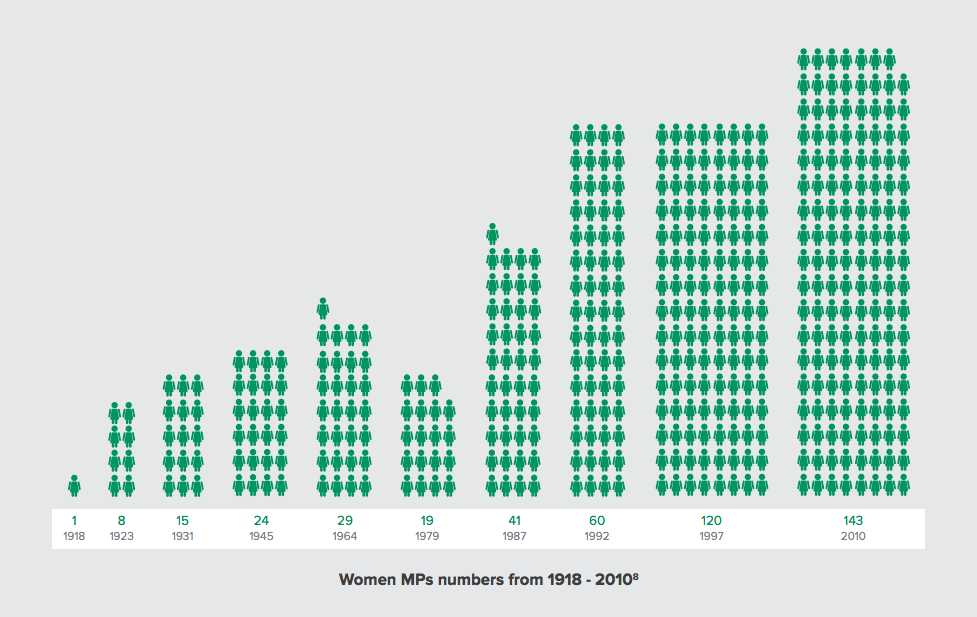

In 1928, with the passage of the second Representation of the People Act, all British women over the age of 21 gained the right to vote. Eighty-seven years later, women make up 22.6% of parliamentarians in the House of Commons and 22.8% in the House of Lords.

There are currently 147 women in the House of Commons – the highest number ever, both in number and in proportion. But the UN ranked the UK 64th in the world in 2014 in terms of gender equality in parliament, behind Sweden, Cuba, South Africa, Finland, Ecuador, Belgium, Senegal, the Seychelles, Nicaragua, and 55 other countries.

There are more men in the House of Commons right now than the total number of women MPs in the history of parliament. (In 1992, there were more MPs named John or Jonathan than there were women MPs.) A hundred and seventy-seven more female MPs would be needed to achieve a parity. The last three general elections added an average of eight women MPs apiece. At this rate, it will take about 22 elections, or 110 years, to achieve a 50:50 parliament.

This is Frances Scott. She's the founder of the 50:50 Parliament campaign, formed because she's not willing to wait 110 years for parity.

Scott has started a petition on change.org that calls for a debate in parliament to establish a plan of action to reach a gender parity in the House of Commons.

She's a whirlwind of energy, her sing-songy voice suggesting a certain middle-aged, middle-class respectability.

She was a businesswoman once, in “the time of big shoulder pads and power women,” as she put it, climbing the ranks to become the first woman in several executive positions in her company. While she knew that she was treated differently at times for being a woman, at the end of the day, she had a “wonderful, wonderful time”.

Now she teaches antenatal classes part-time, and describes her day job as "shopping for the family".

She's brand new to activism. Her interest in gender equality in parliament was first piqued years ago when her daughter was elected to her primary school’s student council and explained to her mum that every year, one boy and one girl were elected to represent the class. Why? Because boys and girls “have different experiences”.

For example: “Boys don’t understand the dilemmas of whether girls should wear trousers or skirts to school; and girls don’t understand the state that the boys’ toilets get into, and how dirty they become.”

These wise words from her young daughter caused Scott to think, as she recounted ecstatically, “Ka-ching ka-ching, this is interesting! They get it at primary school that girls and boys have some different experiences. And I start talking to people about it, and saying, well, hey, wouldn’t it be quite nice if we had 50:50 parliament?”

Quite nice indeed.

She began talking about her idea, with her family and friends, and the other mothers at her children's school. And what did most people say to her?

“People just told me to shut up, you know, and everything’s fine.”

Nevertheless, a seed was planted, and grew in Scott's mind to the consuming passion that it is today. “If I don’t do this, I’m going to burst,” she exclaimed, almost surprised at her own zeal. "I just have to do it. It’s really weird when you have something like that."

Now, this well-off London mother is speaking at more and more conferences, events, and universities, working in some way or another every single day to promote her campaign and her petition. So far, the petition has about 5,600 signatures and is picking up steam, with people leaving enthusiastic comments, such as one supporter's simple line: "Parliament needs to better represent the whole of society."

While Scott's 50:50 campaign could be interpreted as a logical end point of feminism – the equality of the sexes – but she's not quite sure if she's a feminist. Not yet, anyway.

“I’m a woman," she replied, when asked outright if she considered herself a feminist. "I am a woman. I believe in gender equality. That’s kind of the bottom line, as far as I’m concerned. If that defines me as a feminist, then maybe. I don’t really know a lot about feminism. I just care passionately about women. And I care passionately about empowering women, in whatever sphere they choose to be in.”

Scott is also quick to point out that a gender-equal parliament would be of benefit to society as a whole: "This campaign is not just about female empowerment. It's about drawing upon the whole population – and not just the 49% that are men – to help make for a better, more representative parliament." To this end, many of the campaign's placards bear the slogan "Best of Both", a simple response to critics of the campaign who suggest that adding more women to parliament would mean displacing better-qualified men.

Now that Scott is at the helm of about a dozen young organisers, she is eager to draw from the expertise of those who are "tuned in to modern feminism", in much the same way she will apologise that she is not.

An outsider to politics, and to the sometimes competing strains of feminism, Scott is not necessarily the most experienced campaigner. Her lobbying skills are limited and she questions how the campaign use social media and what other campaigns and campaigners should it ally with. Her concerns also include how to include trans identity and gender nonconformity within a campaign of this kind.

Does she even think she has the right to lead such a campaign?

“I’m not sure I do!" she laughed. "I’m sure many people probably think I don’t. Why should I? I have no reputation. I can say whatever I like. I have nothing to lose.

"I can look foolish," she added, then whispered, "I don’t think you need to say that last bit!”

But the ability and the willingness to risk looking foolish is, after all, the activist's great advantage over the elected representative.

The plan, then, is to make friends and not alienate people, all while trying to build a political consensus among potential allies of the 50:50 cause.

That's it: just a simple call for action. The petition’s core text says:

Right now there are only 148 women MPs in the House of Commons – that’s just 23% of the total. We are petitioning for debate around this issue. We would like party leaders from across the political spectrum to make a proper plan to address this under-representation. Changing the status quo is vital because representation shapes policy and policy affects women. Women are 51% of the population. We would like men and women, the best of both, in roughly equal numbers, forging legislation for the future, together.

In fact, the 50:50 campaign is explicit in its lack of specifics about how a gender equality of representation should be achieved.

In her speaking engagements, Scott does, in any case, refer to a number of options for how gender equality could be achieved, including those which have had success in the 63 countries ranked above the UK in the UN's report on women in parliaments around the world.

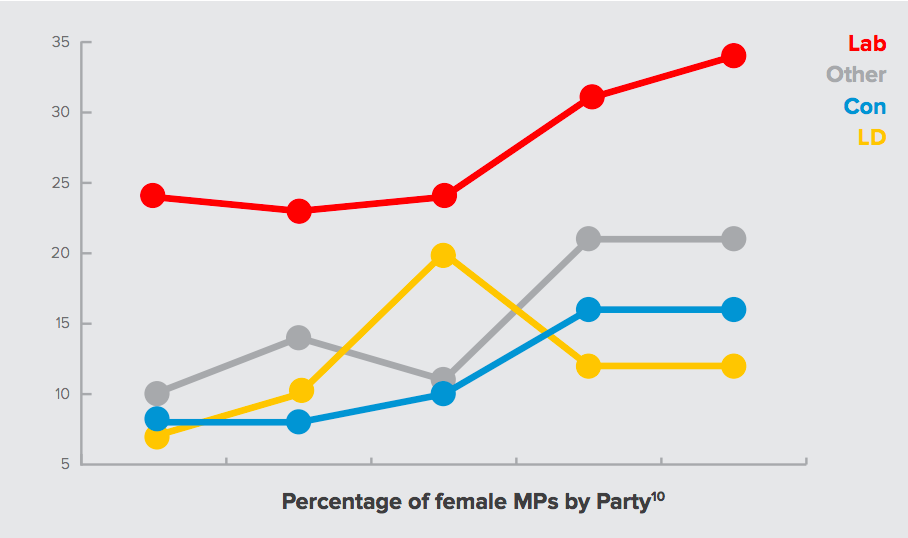

One option is to increase the numbers of all-women shortlists in winnable seats, a strategy used by the Labour party to bring in 101 women MPs in 1997. (Scott quips: “We’ve already had all-men shortlists for years!”) The Tories, meanwhile, increased their numbers of women MPs through the so-called A-list – an initiative which has since been dropped – in which a list of between 100–150 women and ethnic-minority candidates were chosen to stand in safe or winnable seats in the 2010 election. About half were elected.

Other options for achieving gender equality in parliament include 50:50 shortlists, job shares (as proposed by the Liberal Democrats), quotas, or the proposal by Tony Benn to introduce two-seat constituencies: halving the total number of electoral districts and electing a male and a female MP for each.

Scott is an idealist and a pragmatist all at once. But she may be overly optimistic about how much change can be achieved.

On the one hand, her petition is a simple proposal to work explicitly within a system in order to change it, and her campaign is cross-party. The PowerPoint presentation she pulls out at various speaking events boasts a collection of tepid quotes from all the major political party leaders, and she’s managed to photograph MPs from across the political spectrum in her T-shirt.

Even when she mentions Benn, Scott shies away from expressing a political allegiance to the populist leftist icon – “a lot of people consider him to be really radical,” she told me, nervously.

Will it someday seem like common sense that parliament should be made up of roughly equal numbers of men and women, the same way it is now common sense that women should be able to vote? And what role can a campaign like 50:50 Parliament play in nudging British society toward that new brand of common sense?

Most parties are genuinely keen to increase the number of women candidates but parliament's awful working hours, the strain on family life, and media intrusion all work to put many women off. Not to mention the fact that most political careers only start to take off when you're in your 30s – and MPs who take maternity leave are still looked down upon by some in Westminster.

In short, even though many politicians may agree with the 50:50 campaign's overall objectives, Westminster is still a relatively unfriendly place for women, and ambitious young men are still unlikely to forsake their own shot at becoming a politician in the name of wider equality. In reality it could still take decades to hit the 50:50 target as current male MPs retire at each election and new female candidates are put into safe seats.

Despite all this, in a dismal room above London’s Feminist Library, with its worn-out chairs and rickety tables spread with 50:50 T-shirts now available in the colours of the 1920s suffragists – green, violet, and white – a room full of young people worked to make Scott's idea a reality.

In that space, the 50:50 campaign appears to be something much more than one woman’s retirement project. If this petition is to gain real traction, and if the 50:50 campaign is to ever move above and beyond its petition's simple demands for a "debate" and a "proper plan" alone, it will happen because of the willingness of a room full of energetic activists to make their way to a dilapidated old building in Elephant & Castle on a bitterly cold night. They face a massive struggle against vested interests and the brutal reality of Westminster but they truly believe they can imagine a new model for democratic representation – and convince others to work towards the same aim.

One woman can only do so much. A whole room of women, though, looks more like the beginnings of a movement.