Like a lot of people these days, I know how to Spotify but not spackle. Living in New York with a superintendent in the building, this wasn’t a problem. But a decade ago when I moved into my own house outside the city, built in the 1970s and in need of some repair, I needed a handyman. After I put out word, an older woman who’d been in the area for a while responded cryptically, “I might have someone for you.” Then, nothing. It was like she was sizing me up. A few weeks later, my sink was leaking and I bugged her again until she reluctantly relented. “I’ll ask my guy to stop by, but don’t give out his number,” she told me curtly, then slipped into a whisper, “He’s a celebrity.”

Though he did do home repair in his spare time for fun, she went on, Jordan Clarke’s day job was being a star of daytime soaps. Over a span of 26 years, he had been portraying Billy Lewis, an avuncular and alcoholic patriarch on Guiding Light, the hit TV series that set the Guinness Record as the longest-running TV drama in history. Most actors would be lucky to have the same role for one decade, let alone three, which made Jordan’s unique career all the more epic. This was why she didn’t want to be indiscriminately giving out his number, she said — he was still on the show. There were homemakers — die-hard fans — across the town who wouldn’t leave him alone if they knew he could be working for them.

“No problem,” I said, playing it cool — then looked him up the second she left the door. Jordan wasn’t just a soap star, I found on IMDb, he was a veteran character actor — making appearances on all my favorite shows growing up. He was on M*A*S*H, Fantasy Island, holy crap, the guy was on Knight Rider. I wasn’t a soap fan, having only watched a few episodes of All My Children while high in college, but no matter. Jordan was the real deal, an Irish Spring–era star who rode the crest of daytime drama long before reality TV and YouTube fragmented pop culture.

The next day, I opened my front door to find a chipper, tall guy in his late fifties with graying short hair and glasses, grease stains on his Merrells and tool belt. “You must be Dave,” he said, with a Hollywood smile and a firm handshake. “I’m Jordan Clarke.” As I showed him around to my leaky faucet, I wanted to learn more from him — not just about home maintenance, but what it was like bask in the golden age of kitschy TV melodrama that filled the days of so many lives. And, yeah, I wanted to know what it was like working with Don Johnson on Miami Vice.

The next time he came by, he told me how he got into acting. He grew up in the farm town of Webster, New York. “My dad didn’t know how to use electricity,” Jordan joked as he cranked his wrench on my faucet. Jordan didn’t know much about fixing things either. Though a brawny 6'4" extrovert who was a hammer thrower at Cornell, Jordan preferred more high-minded pursuits. He studied philosophy, and discovered acting in college, moving to New York in the early 1970s to train at New York University.

After getting cast in a wine commercial, Jordan got called to an audition at the CBS studio in New York one morning in 1974. At the time, CBS was riding high as the so-called Tiffany Network, nicknamed for its sophisticated, programming-classy stature, and Jordan walked into a room of snooty producers in snazzy three-piece suits. It was an audition for one of the biggest shows on daytime TV, Guiding Light. The show had a storied history, starting out as an NBC Radio serial in 1937 before moving to CBS television in 1952. Following the interpersonal dramas within a family of middle-class German immigrants, Guiding Light helped to establish the pillars for every ensuing soap on TV: family, romance, backstabbing, and betrayal.

Though Jordan had never seen a soap, let alone this show, he was like any other young, hungry actor dreaming of a big break. So when he got the audition to play Dr. Tim Ryan, a swaggering obstetrician, he gave it his all, he told me, as he screwed the faucet back on the sink. “I was appropriately fiery,” he said, with a self-deprecating shrug, “and they loved it.”

In between fix-it visits to my house, I’d hit up YouTube, watching clips of Jordan bellowing his lines on the flatly lit sets. The fact that I had a front-row seat to his surprising double life amazed me. One day he was off to New York to tape an episode, the next he was at my place putting up my shower bar. Of course I wondered why he was doing this handiwork, but didn’t want to pry. So instead, if I passed by him working on my way to get a coffee, I’d pick up his story, and he’d be happy to continue it along. I was a writer, and he was an actor, after all, we could speak the same language.

Jordan likes to tell his war stories, and would pull up a stool and happily recount his adventures. Being on Guiding Light, he told me a few months later, was a lot of pressure. The show was consistently among the top daytime programs, hitting several million viewers per episode. With five half-hour-long shows airing Monday through Friday (the show wouldn’t become a full hour until 1977), the production was fast and furious, with as many as seven episodes taped a week. Jordan and the rest of the cast had to memorize long tracts of dialogue quickly and accurately during days that could last up to 16 hours. There was no time for mistakes. “There was no editing,” recalled Jordan one afternoon as he moved an electrical outlet. “We shot without stopping.” But having grown up on a farm dreaming of acting, he was willing to do anything to keep his job. “I was so happy to make $400 per week, I could have killed,” he told me. “They pay you to solve problems, they don’t pay you to kvetch.”

Jordan’s early dedication paid off. He got the attention of Hollywood scouts, and took leave from the soap in 1976 to try his luck in L.A. — which is how he landed on the same shows I’d watch after school while eating Life cereal. Some television executive thought he had a stroke of genius: The Fonz Goes Elizabethan. The 1977 CBS TV special was called Henry Winkler Meets William Shakespeare, and Jordan was cast opposite the moonlighting Happy Days star as Mercutio, Romeo’s witty but temperamental friend. But as Jordan stood under the spotlights by Winkler, the cocky Fonz — who traded his leather jacket for a blousy white smock — seemed a lot more shaky than usual. Jordan found the TV heartthrob struggling to fit in and break from his image. “People would come to the door and say, ‘Hey, Fonzie,’” Jordan recalled, “and he’d say, ‘No, I’m Henry.’”

But it was Jordan’s next big role that really piqued my curiosity: his guest spot on M*A*S*H, my favorite show as a kid. It was an episode called “The Smell of Music,” the one where Hawkeye and B.J. refuse to shower until their effete roommate Charles quit playing his annoying French horn. Jordan was in the dramatic subplot, playing Saunders, a depressed soldier who is disfigured after being injured and wants to kill himself. I tracked it down online, and there was Jordan on my laptop monitor: thinner, dark-haired, and brawling with Colonel Potter as he tried to poison himself with gas. “It’s stupid,” he told me one day soon after as he fixed a leak in my ceiling, “because if you inhale gas you’re going to pass out and then just come to.”

A year passed since his first visit to my house, and I had become almost eager to have stuff break down just so I could learn more. It was like he was becoming my own personal soap star, entertaining me during the long daytime hours. As he told me, more guest spots followed — The Paper Chase, Three’s Company, Norma Rae, Knight Rider, Miami Vice. He played a killer on Fantasy Island, and a rapist on The Waltons. “I can still remember my lines now,” he told me one afternoon at my place, where he was replacing some tile. “Hey, Mr. Walton,” he said, with the Southern twang of his character, “those young girls sure do look pretty in their thin summer dresses.” He went on, “You’re always the bad guy on those shows because the good guys are the stars.”

There was a price for his bad boy fame. He was at a racetrack in Los Angeles when a woman threw a hot dog at him for having dumped his fictional pregnant girlfriend on Guiding Light. “In their minds you’re as real as most anyone else in their lives,” he told me one summer day, while cleaning my gutters. "It took me a long time to understand that’s OK.”

But in 1983, he got a chance to become the big man again when the soap’s producers called him back to take on the role of Billy Lewis, the character that would become his legacy. Billy wasn’t always good: Once, according to his lengthy rap sheet, he tried to kill someone while he was hypnotized. But Billy was likable in a salty way. After his time bouncing between parts in Hollywood, Jordan was happy to be back among the cast and crew who felt like family. “I never had a brother,” he tells me, “but my brother on the show kind of felt like one.” Drawing on his Ivy League training, he imbued his role with the kind of depth that made Billy relatable. “I played it with humanity,” Jordan says. “I made him the redneck with the heart of gold.”

It worked, and he started earning the kind of fame and fortune that could only happen during the heyday of daytime drama. A woman from Texas wrote him asking to impregnate her, and a guy in Rochester wanted him to go on the air in no underwear. While eating breakfast at a Waffle House in Georgia at 4 a.m., a family showed up in their pajamas to get his autograph after hearing he was there. There were late-night parties at the Chateau Marmont. Jordan got mobbed at personal appearances down South. He’d get flown in first-class to personal appearances at malls around the country.

When he touched down once in North Carolina, he was met by three women who told him, in no uncertain terms, that they intended to sleep with him before he left. Guiding Light found an audience outside the U.S. and became a primetime hit in Italy, where Jordan needed bodyguards to get through the mobs. Even decades later, his charm hadn’t worn off. When my sister-in-law heard he was my fix-it guy, she begged me for a signed headshot.

But despite the success, Jordan told me one day as he spackled my foyer, he was struggling. When he was 33, one of his young daughters drowned, a tragedy that left him with chronic anxiety. “That fucks you up in such a way,” he told me, tears filling his eyes. “Your worst nightmare comes true, and there were times I didn’t want to leave the house.” Being in the acting business with money to spend, it was easy to find an escape in drugs. One day he showed up on the set of Guiding Light, and confided in one of his longtime co-stars about his troubles. “I’ve never seen you like this,” she said, with concern. “Am I going to be OK?” he asked. “Yes,” she replied, “you’re going to be OK.”

As Jordan recounted the story, I choked up. I’d just wanted to be entertained at first, but now, a few years after meeting him, he’d become a friend, and I felt for the guy. And, I learned, this is what brought him to my doorstep — and the others in town — in the first place. Being a handyman was a kind of therapy. Raising his family on a ranch in Jersey, he liked the outdoors, the horses, and began doing odd jobs for his neighbors. It gave him a special satisfaction to be out and about, working with his hands. When others asked for help, he soon began doing handyman work to get himself out of the house on his days off.

Fixing things had a tangibility that, after all these years reading lines, he craved. He savored the satisfaction of making a new cabinet and seeing it being used in someone’s home. There were no lights shining down, no directors giving him orders, no egotistical co-stars. There was just him, a hammer, and a problem to solve. “As wonderful as acting is,” he told me, “this is more satisfying.”

By the time he was working with me, he had kicked his dependencies and was on top of this game. In 2006, he was installing a new shower head for me one day, and the next, winning a Daytime Emmy for Best Supporting Actor in a Drama Series. And he didn’t even tell me. I stumbled on the news while he was away, and watched him accept the award on YouTube, hoisting the statue into the air. “It was one of the best moments of my life,” he told me, when he returned the next week to finish working on my shower, “to look out on my family and these people I’d been working with for so long.”

But the party was coming to an end. Reality TV and talk shows were killing the soap opera star. I’d always thought it was the rise of the internet that sucked the eyeballs away from daytime TV, but Jordan said it was mainly the Oprahs and Ellens. Networks found that talk shows could get big audiences with lower production costs than franchises like Guiding Light. “They could make reality shows for nothing,” Jordan said, with a sigh. The golden age of soaps was done. And in 2009, after 57 years on TV, the longest-running TV drama of all time, and Jordan’s home, Guiding Light went dark.

Though Jordan had seen the end coming gradually over the past few years, the news hit him hard. In the weeks after the cancellation, he stopped coming by my place, and wasn’t returning my calls. I grew concerned until one day my doorbell rang, and there he was again in his blue knit hat and muddy Merrells. “I had a stroke,” he told me with a sigh. He looked the same, but as he walked in with a slight limp told me he was still feeling unbalanced. Jordan had gained weight in the recent years and been battling health challenges. Not long after Guiding Light was canceled, he suffered the stroke. Just like that, his career and his vigor seemed gone.

But Jordan didn’t seem to be taking it so hard at all. He still showed up chipper as ever. There was something that was still keeping him going — being a handyman. As we talked about the plans for stripping out my old chunky wall unit, that’s when it hit me: I’d been so fascinated by his life in the past that I failed to see how much he’d learned to take pleasure in the present. This is what enabled him to survive life after the soap bubble burst. And this is what I wanted to learn for myself: how to step away from my work and life online to pick up a hammer and fix something real. And so he became a new kind of daytime star for me: Bob Vila. In subsequent visits, he schooled me in the home maintenance essentials: stocking my toolkit, spackling walls, fixing my sink. We spent a day swapping out my rusty 3½-inch pulls on my kitchen cabinets with the shiny 3-inch stainless ones from at Home Depot. He handed me his $400 drill but as I squeezed the trigger, he stopped me. “You need to flip that little black switch,” he said. “It’s in reverse.”

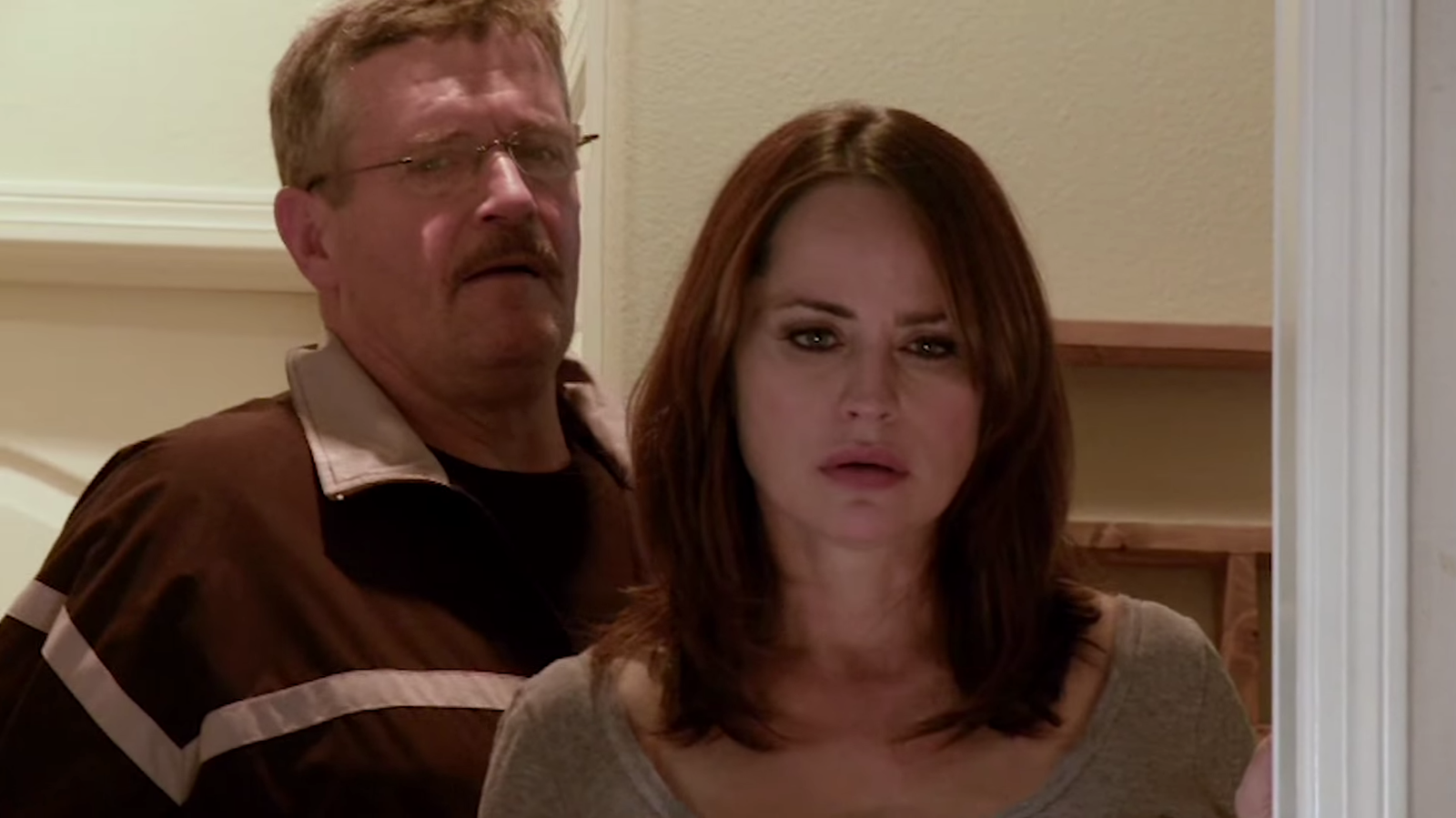

Ever since, I’ve learned quite a bit from Jordan not only about home repair, but about drive and determination — just the stuff that had fueled him during his long run in TV. I changed a doorknob, a toilet seat. Soon enough, Jordan was feeling better, and taking on more jobs — including ones on the new generation of online soaps. Since the demise of Guiding Light, Jordan has reunited with one of his co-stars in an Emmy-winning web soap called Venice, where he plays John Brogno aka the Colonel, a crotchety dad who disapproves his daughter's lifestyle.

Though daytime soaps are all but gone, the pathos they pioneered have gone wide — from the Kardashians to Empire. “When you read the recaps of Game of Thrones, it reads just like the recap of a soap,” Jordan told me the other day, as he was clearing one of my pipes, “but it’s just a lady with a dragon instead.” Then he picked up his wrench and got back to work. “Melodrama is in everything,” he said.