Nicholas Sparks movies sell the idea of being old-fashioned, and they sell it consistently and well. The Sparks oeuvre is now 10 movies strong and counting, with number 11, The Choice, done shooting and set for a release next year. And the fact that they pretty much all hew to the same formula with marked dedication has become a selling point.

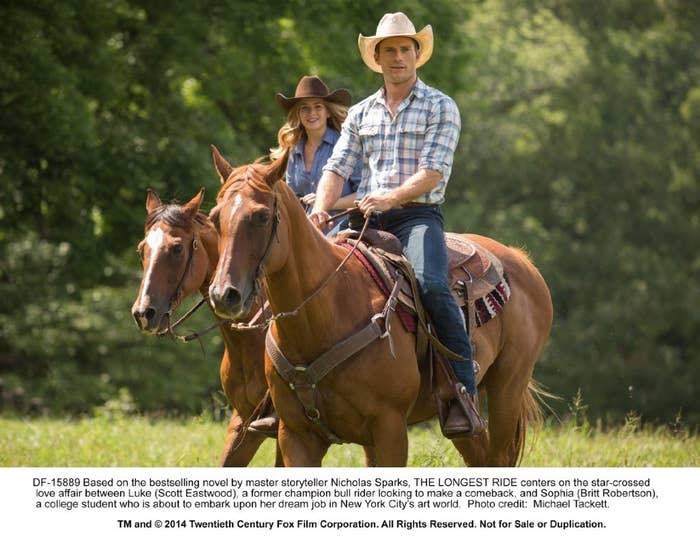

It doesn't matter that their casts are generally led by the latest in buzzed-about beautiful faces — The Longest Ride, which is directed by George Tillman Jr. and opens April 10, stars Scott Eastwood and Britt Robertson. Or that their settings are contemporary ones in which everyone wears jeans all the time, carries a cell phone, and has no qualms about indulging in a little soft-focus sex when the moment is right. They deliver a very specific kind of hit, harkening back to a gentler, more civilized era that never really existed, but that makes for a very cozy place to visit on screen.

It's an era in which the men are strong but tenderhearted and committed, the women radiant but wary, needing to be wooed in some swoony fashion that hopefully involves kissing in the rain or in a shower. When Luke Collins (Eastwood) picks Sophia Danko (Robertson) up to take her out on their first date in The Longest Ride, he strides through her college campus and up to the front door of her sorority house wielding a bouquet of flowers. He's a cowboy, a professional bull rider on the PBR circuit, but in that scene, he looks like he might as well be a time traveler visiting from another time and place.

The Longest Ride is a weak sauce addition to the Sparks empire, a little better than last year's The Best of Me, but miles below uber-Sparks work The Notebook. But the otherwise wan The Longest Ride has one thing that sets it apart: a quirk of casting the children and grandchildren of Hollywood icons.

Scott Eastwood, the son of Clint Eastwood and the primary product The Longest Ride, is pushing in what's his biggest role to date. He's not a terribly charismatic performer, though the movie's less concerned with his acting ability and more interested in the wattage of his smile and how he takes off his shirt, something he handles with aplomb.

But he does look strikingly, fascinatingly like his dad as filtered through the more contemporary screen hunkiness of the Chrises Evans and Hemsworth. It's impossible to shake — he's prettier and softer, but can't help but recall some of the famous screen cowboys the older Eastwood's played every time he appears on screen, especially when, in his one moment of sharpness, his character tells an art dealer of her show, "I think there's more bullshit here than where I work."

Eastwood adds to the movie's Sparksian temporal fuzziness and sense of remove, one that's fueled by the way it looks unfailingly like a North Carolina tourism board commercial in which the sunlight's always as buttery as a croissant unless an emotional or sultry moment would look better in the rain. There's the picturesqueness of a idealized memory that never ends in Sparks adaptations, compounded by the frequent use of flashbacks. The Longest Ride flashbacks actually are idealized memories, a polished-into-generic vision of the 1940s, '50s, and '60s as recounted by the story's doler-out of wisdom, Ira Levinson (Alan Alda).

Boardwalk Empire alum Jack Huston, grandson of legendary filmmaker and actor John Huston, and Game of Thrones alum Oona Chaplin, granddaughter of Charlie Chaplin, play the younger version of Alda's character and that of his late wife, respectively, as they fall in love and overcome hardships during and after World War II.

Huston and Chaplin may not provoke the same immediate recognition that Scott Eastwood's not-quite-famous mug does, but they're the descendants of two venerable Hollywood dynasties, and they bring some ballast and quirk to a overstuffed backstory that incorporates the Jewish community they're a part of, war injuries, and the Black Mountain College. The two even steal the focus from golden couple Eastwood and Robertson, who — in the present — have far less weighty drama to deal with, as they fight over whether Luke will continue in his bull-riding career despite a life-threatening injury.

As the Levinsons struggle over whether their marriage can survive infertility given their desire, in the wake of the Holocaust, to have a large family, Luke and Sophia's problems start to seriously pale in comparison. When your present-day stakes involve whether or not to take an internship in New York, it's hard to fault the movie for tipping toward the past.