When I was in college, I stood on a stage in front of 100 people and told them that I hated my thighs and that I hated my vagina even more.

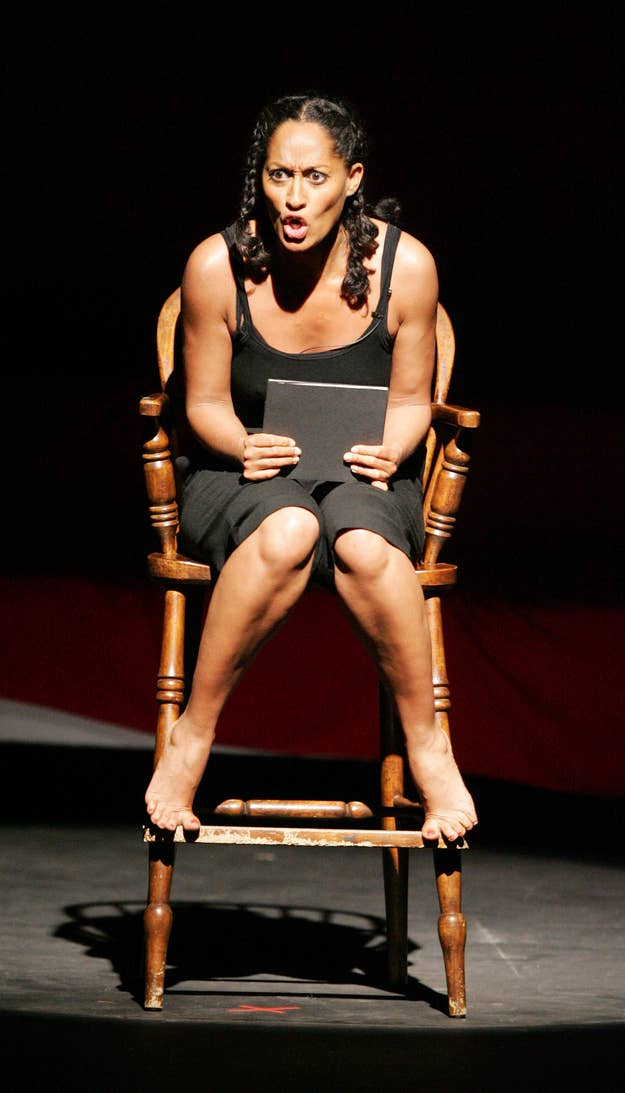

I was performing in "The Vagina Monologues," which I'd seen every year at school (I liked watching my friends perform and I liked yelling "CUNT" with the audience at a key moment of the show), but wasn't a part of until my last semester senior year.

Originally performed by its author, Eve Ensler, as a one-woman show in 1996, "The Vagina Monologues" are comprised of interviews conducted with over 200 women of all ages and backgrounds. Using the proceeds from ticket sales of the play — which is free to reproduce — as well as its momentum, Ensler started a global activist movement called V-Day, which raises money and awareness to end violence against women around the world. In 2012 alone, 5,800 V-Day events took place, and to date the organization has raised over $90 million. Performances of "The Vagina Monologues" and other V-Day shows and events are currently taking place around the world, on college campuses and in local communities, from February 1st through April 30th.

However, the play may only be performed under the condition that Ensler's original text not be changed. This lies at the root of the show's modern criticisms: how is an at times politically incorrect feminist play written 17 years ago relevant today, when people like Lena Dunham have built huge platforms (Girls, and likely her forthcoming memoir) with which to explore female sexuality, transgender women compete in Miss Universe, and the country has become much more concerned with political correctness overall? With all its flaws, is "The Vagina Monologues" — which refers to the vagina as everything from a "monkey box" to a "nappy dugout" — still useful?

Yes. Because few other rallies or panel discussions or club meetings bring such a large variety of women together like this play, which addresses topics as serious as rape alongside ones like dissatisfaction with one's body. Perhaps nothing else unites women, especially in college, as effectively for the purpose of combating female assault on a global scale and for talking about issues that are deeply personal (and often unaddressed). Putting on and going to see "The Vagina Monologues" is a kind of activism that hardly feels like activism at all.

Some argue that "The Vagina Monologues" reduces women to their vaginas, conflating liberation with bodily acceptance. "I am more than my vagina," wrote blogger Jenae S. on feminist site The F Bomb. She notes that the play fails to take into account transwomen, or people who identify as female but who don't have vaginas, and that sex between women is presented as far more positive than heterosexual sex. (In one monologue, a teenage girl gets drunk and has fun, meaningful sex with a beautiful older lesbian, which she describes in the play's original text as "a good rape.") And Aswini Hardikar wrote in Campus Progress that the play "claims to represent a broad spectrum of women, but the show's monologues are delivered almost exclusively through the lens of a white, upper-class, Western female perspective."

My monologue was one of the most debated and disliked among our cast. Titled "Because He Liked To Look At It," it was about a woman who thought her vagina was ugly until she met a completely ordinary man named Bob. Though he doesn't like spicy food or driving fast, Bob loves vaginas. At one point in the monologue, Bob gazes at the narrator's vagina and she becomes so uncomfortable that she asks him to stop. He refuses. Although she comes out of the experience feeling wonderful and new, finally loving her body, she's also been violated.

The 20 or so of us cast members sat on the floor of a freezing classroom during one rehearsal, sometime close to midnight, talking through each line of the piece. Some of us took issue with the idea that this woman doesn't feel beautiful or validated until she's given permission to by a man; even more of us objected to Bob not stopping when the narrator asks.

But the monologue responds to criticism itself, with these opening lines: "This is how I came to love my vagina. It's embarrassing because it's not politically correct." My castmates and I agreed that it wasn't politically correct or universal. It was one woman's experience, which may not be useful to everyone else but was incredibly moving for her. We decided that her experience was valid, as were all of ours, and this became our mantra and our goal.

With this in mind, we learned to listen to each others' arguments and use those views to evolve our own. We held discussions with the audience after each performance to hear what our friends, family members, and professors had to say about what they'd just seen, and every night someone would raise an insight we hadn't considered in our dozens of hours of rehearsal. In this way, the show became much larger than the text and even our performance, reverberating outward into our school's community and beyond.

We rehearsed the show for three weeks and performed it for just three nights. And while we never came to satisfying conclusions about the text's failings, that was actually part of the beauty of the process; it showed us that "The Vagina Monologues" isn't meant to be an all-inclusive work of art — it's a jumping-off point for discussion about the often uncomfortable topic of female sexuality, and a way to unite women in doing so. If we're going to have these conversations, we realized, they had to begin with our being able to say the word "vagina." The play's dated moments made us consider the present day; its prejudices gave us an entry point to talk about our own. One of my great friends, who co-directed our production, said, "There's no one way to be a good feminist or a good woman."

"The Vagina Monologues" and V-Day provide a space to begin to figure out how. The movement is growing rapidly: for its fifteenth anniversary this year, it launched One Billion Rising (a name that refers to the statistic that one in three women will be raped or beaten in her lifetime) which raises awareness with flash mobs across the globe. You can watch livestreams of "risings" from New Delhi to Jerusalem to Steubenville, Ohio, here.

Being in "The Vagina Monologues" was a wonderful way for me to become close to a strong, singular group of women. Some of them I'd already considered friends, while some I'd only seen in passing on our tiny campus, but by the end of those three weeks it felt like they were all, in some small way, a part of me. This is the play's power and something it'll surely do for countless women to come. And with just sitting on classroom floors, with cheap wine and good conversation standing in for rallies and slogans, the Monologues help continue the fight for the rights of women everywhere.