Each spring, when you walk into a Walgreens, you’ll see red noses on sale by the counter. They’re only for sale at Walgreens, and they support Red Nose Day on May 25. You can read the box and tell that buying a nose helps a kid in need and that all profits go to helping end child poverty. Still, it’s hard to know what that really means. Ending child poverty is a big, lofty goal, and it can be hard to imagine how such a thing could realistically be attained. How could this nose you’re buying along with a pack of gum actually ease the suffering in a child’s life?

Let’s break it down: All Walgreens profits from red nose sales go to the Red Nose Day Fund. Comic Relief, the organization behind Red Nose Day, grants your donations to organizations that help kids in three distinct areas: health, education, and safety. Half of your donation goes to charities here in the United States; the other half goes to organizations that work tirelessly to help children all across the globe who are living in poverty. In 2015 and 2016, Red Nose Day helped kids in the United States and 25 other countries to be healthy, educated, and safe from harm.

But even this kind of breakdown can feel abstract. Putting a human face on things goes miles toward understanding how much you’re doing when you buy a red nose. To that end, we (my photographer, Aubree, and I) bought red noses from Walgreens. You can actually see a picture of me doing that at the end of another post. Then, we took a trip to see, in action, how the donation from our red nose purchase at Walgreens turns into actual aid for kids around the country and the world.

To see how the money from Red Nose Day helps children living in poverty, we visited New Orleans, Louisiana. New Orleans’ beauty and culture are known around the country and the world. The city’s struggles are also well known. It’s almost impossible to talk about New Orleans without mentioning Hurricane Katrina. The destruction and displacement caused by Katrina is so ubiquitous that residents simply refer to it as “the storm.”

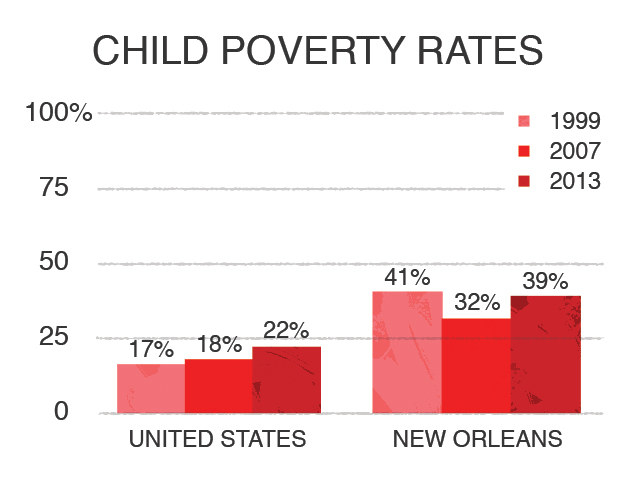

But to just talk about Katrina would be to overlook some of the more tenacious aspects of poverty in New Orleans. Specifically regarding child poverty, the city has been in need for a long time. Research from The Data Center shows that the city has been significantly above the national average for child poverty for quite some time. Issues like food insecurity, lack of access to quality medical care, and the prevalence of low-wage jobs in New Orleans all contribute to the region's high child-poverty rate. These issues may not be as dramatic as the storm, but they still play a big part in the lives of the kids we spoke to.

Forty-one percent of New Orleans’ kids lived in poverty in 1999. In 2007, two years after Katrina, that number had shrunk to 32%. By 2013, that number was slowly creeping up again to 39%. It’s almost as though our national attention after the storm was on rebuilding New Orleans and lifting the whole city out of poverty. Then, as our attention shifted to other topics over time, poverty began to rise again.

But to just talk about Katrina would be to overlook some of the more tenacious aspects of poverty in New Orleans.

Luckily, Walgreens is selling red noses now to help children in New Orleans and all around the country. The stories we’re about to hear represent just a small sliver of the people who benefit when you pick up a red nose at the Walgreens counter.

The Data Center points out another concerning aspect of child poverty:

“High poverty levels among New Orleans children are concerning for the long-term economic prospects of the city because of poverty’s effect on child brain development.”

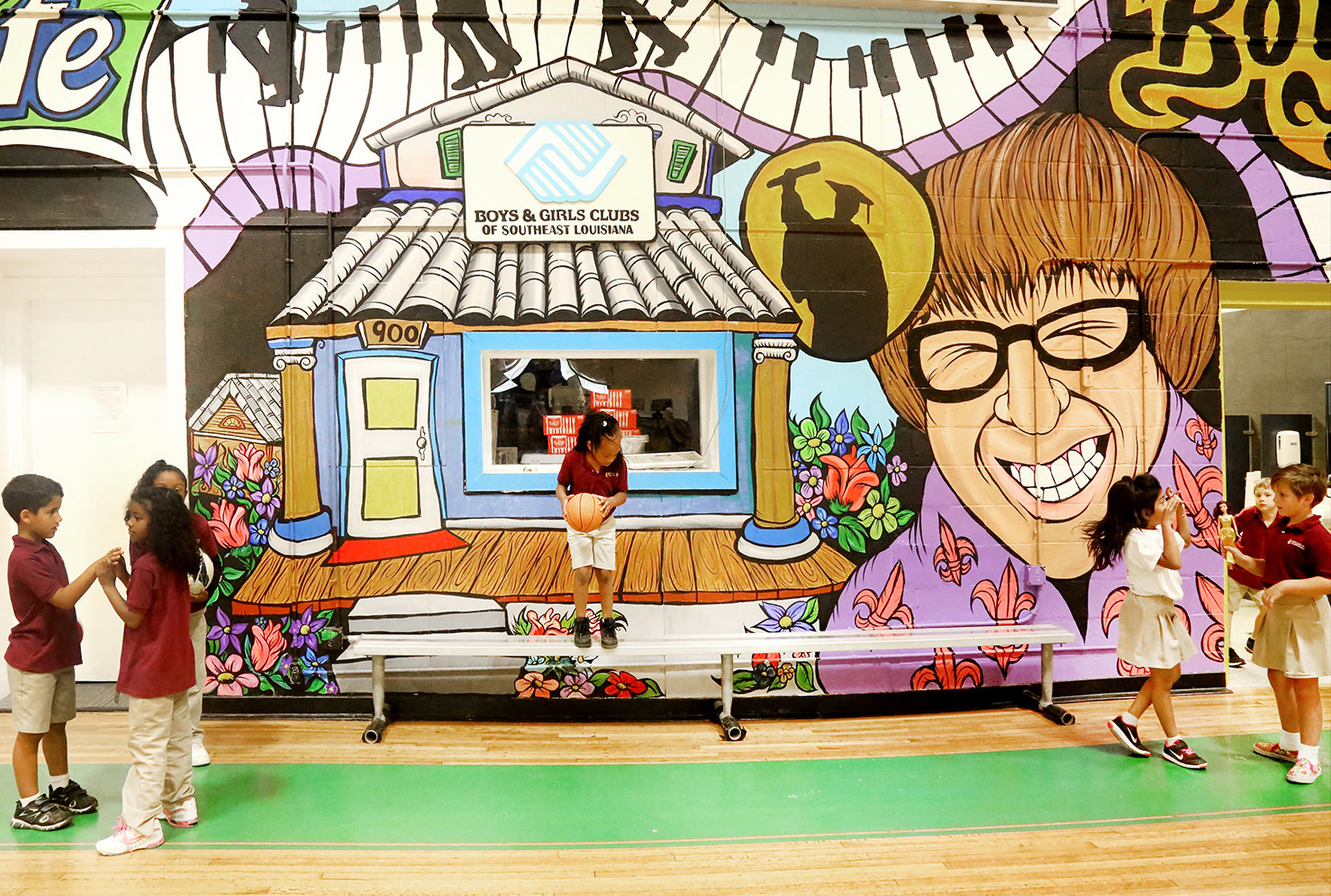

It’s for that reason Red Nose Day helps fund education programs for kids — such as Summer Brain Gain, a program run by Boys & Girls Clubs of America. Their website for the program states that “during summer, most youth lose about two months' worth of math skills. Low-income youth also lose more than two months' worth of reading skills, while their middle-class peers make slight gains.”

When we visit the Westbank Club in Gretna, Louisiana, Thomas H. Falgout, the CEO of Boys & Girls Clubs of Southeast Louisiana, says the program is designed to be enjoyable for the kids. “They don’t even know they’re learning,” he says. “They’re having fun. But when it [came] time to take that reading test in the fall to see where they are, they didn’t have learning loss from where they were. In some cases they [were] higher than they were before they started the summer.”

Falgout also points out that, for many kids coming from impoverished situations, learning is also about exposure to things you and I might take for granted. “Just take simple things like taking kids to a mall that has an escalator, so they understand what that’s like,” he says.

Learning takes all forms in Gretna. Will Giannobile, Westbank’s club director, tells me about a program where the kids learn about STEM skills like engineering and technology using Legos. He also speaks of a cooking class designed to teach kids healthy eating habits, like cooking shrimp in olive oil instead of butter. Falgout points out that such activities can have a dual learning purpose.

“It’s a cooking class, but you’re also talking about measurements. Math skills!” he exclaims.

Falgout also points out that, for many kids coming from impoverished situations, learning is also about exposure to things you and I might take for granted. “Just take simple things like taking kids to a mall that has an escalator, so they understand what that’s like,” he says. “Then they can relate to things that are very different than what they have experienced.”

Admittedly, I would have never thought of seeing an escalator as a learning opportunity, but that’s me showing my middle-class upbringing. To a kid living in poverty? This is absolutely a valuable, memorable experience. Access issues — whether it’s something minor like an escalator in a mall or something major like availability of meaningful extracurricular activities — are crucial for New Orleans’ kids.

Jamie Schmill is the programs director for the Laureus Sport for Good Foundation USA. Laureus USA — an organization that uses sports “as a tool for social change, intentionally driving youth to achieve.” The United Nations agrees that sport is a powerful tool for social change, as can help promote gender equality, social mobilization, and economic development, and disease prevention. Laureus USA receives some of its funding from Red Nose Day. A New Orleans paper, the Times-Picayune, notes that the price of youth athletics has increased dramatically, so Laureus USA’s work is all the more important for making sure New Orleans kids in poverty get access to sports, just as middle- and upper-class kids would.

To help with that issue of access to sports, Laureus USA helps to fund several local organizations though their Model City Initiative that foster sports as a tool for learning and growing. Two of those organizations are Girls on the Run and Youth Run NOLA, which both use running as a teaching tool.

“This is really about building the foundations of becoming strong, independent women,” says Girls on the Run’s marketing coordinator Kelly Gallagher. That’s achieved through a research-based, 10-week curriculum. Each week, in tandem with their running practice, the girls learn a new lesson. Gallagher says the lesson could be about choosing your friends, how to deal with emotions, having empathy, or a number of other topics.

Program director Renee Grady tells me about one of the lessons about media, advertising, and body image. They pull out magazines and let the girls look at advertising, its messages, and consider whether they interpret those messages as positive or negative. “We just want to make sure that girls understand that, just because one advertisement and one picture says it’s supposed to look like this, that’s not really true,” says Grady.

At Youth Run NOLA, the lesson is one that even some adults struggle to learn: perseverance in the face of seemingly impossible goals. “There’s a constant emphasis on growth and improvement,” executive director Denali Lander says. “Running is a really tangible way to experience that. If you’ve gotten to this finish line, what other finish lines in your life are you trying to get to, and how are you going to get there? What are the small goals to get you to that point?”

Both Girls on the Run and Youth Run NOLA make a concerted effort to include kids who have lived in poverty. Grady tells me 65% of Girls on the Run runners are coming from schools that are on free or reduced lunch, an indicator of poverty. For Youth Run NOLA, Lander says 80% are on free or reduced lunch. Youth Run Coach Rebecca Meaney estimates that number could be as high as 92% at her school, Ella Dolhonde Elementary.

Lander also tells me how grateful she is for Laureus USA, which helped make connections between Youth Run NOLA and Girls on the Run that might not have been possible otherwise. Lander says there can be a natural competitiveness between sport nonprofits as they seek the same resources. Laureus USA’s funding of both groups took away that competitiveness, helping Girls on the Run and Youth Run NOLA to focus on, as Lander puts it, a “collaboration [that] is really beautiful and makes a lot of sense.” When you grab a red nose at Walgreens, you’re helping to make that beautiful collaboration a reality.

The New Orleans Children’s Health Project is a partnership with Children’s Health Fund and gets funding from Red Nose Day. We meet Dr. Kim Mukerjee, a pediatrician for NOCHP, and Jeanne McKay, NOCHP’s senior program manager, at Tulane’s School of Medicine in Downtown New Orleans.

McKay tells me their program was born out of Hurricane Katrina and the response to the disaster. Nearly 12 years later, the issues they face are still connected to the storm, but not in the way you might think. After Katrina, many immigrants from Central America came to New Orleans to help rebuild the city. Initially, adults came by themselves, but growing violence in Central America has led to more and more children making the journey as well. Often, they come by themselves.

“Eight-, ten-year-old kids are coming by themselves from Central America to be reunited with families here,” says Dr. Mukerjee.

Dr. Mukerjee says they estimate between 12,000 and 20,000 refugee kids have come to New Orleans in recent years. “To me,” she says, “that is a disaster. That is a crisis. Because we don’t have the infrastructure to handle this. ...There are thousands and thousands of them who have no one else to take care of them.”

Without NOCHP, she would have never been diagnosed, much less received actual care from doctors like Mukerjee. Thanks to NOCHP, the Children’s Health Fund, and donations from Red Nose Day, she’s getting the care she needs for the very first time.

That is why the NOCHP has stepped up to get these kids the medical care they need and why Red Nose Day is funding their efforts. With their mission and its background laid out for us, Dr. Mukerjee and McKay invite us to meet some of their patients.

The first family we meet is Nina and her three kids, 7-year-old Danny, 5-year-old Nicolas, and 2-year-old Maria. Nina tells me it was a three-month journey from Honduras across Central America and Mexico. They were stranded in Mexico City for about a month and had to sleep on newspapers in the street. For part of the journey, they rode on top of a freight train for 16 hours.

The first time Danny, Nicolas, and Maria had ever seen a doctor in their lives was two weeks before our visit. Because of the arduous journey to America, Danny and Nicolas were malnourished when they arrived. They are now at a healthy weight, and Dr. Mukerjee helps to keep them there. Maria has more complex needs. She has not had a full diagnosis yet, but current signs suggest Down syndrome. Maria needs to see a cardiologist and a hearing specialist. Also, her speech development is delayed, so she’ll need speech therapy. Dr. Mukerjee is helping Nina to get in touch with the specialists that will work with Maria on these issues. Without NOCHP, she would have never been diagnosed, much less received actual care from doctors like Mukerjee. Thanks to NOCHP, the Children’s Health Fund, and donations from Red Nose Day, she’s getting the care she needs for the very first time.

It’s more than physical health that NOCHP is concerned with; several kids we meet have mental health challenges. Because the journey to America is so dangerous, it can be traumatizing for some kids. Dr. Mukerjee introduces us to 13-year-old Mateo, 10-year-old Sofia, and their mother, Isabella. Isabella tells us Mateo and Sofia came to America about three years ago. A coyote (a slang term for “smuggler”) led them, along with some other kids. It soon became apparent to Isabella that the coyote was being violent with the kids on the journey. When they reached the border, the coyote’s rate went up, and Isabella knew her kids were stuck with a dangerous man. Isabella had to sell her car in New Orleans in order to meet the coyote’s demands.

Due in part to this experience, Sofia experiences anxiety. To help kids like Sofia better manage mental health challenges, Dr. Mukerjee and her staff teach breathing exercises and coping mechanisms, like stopping to think about your feelings.

Though their treatment is ongoing, the work the NOCHP is doing helps these kids grow up healthy, as any kid should. When we buy a red nose from Walgreens, we’re doing our part to help that healthy growth occur not just in New Orleans, but in cities all around the country.

Those skills can be therapeutic on their own, but sometimes more help is required. Dr. Mukerjee introduces us to another patient, 15-year-old Daniel, who has had posttraumatic stress disorder since his family was targeted by criminals and he came to New Orleans seeking safety. For kids like Daniel, Dr. Mukerjee and her colleagues works tirelessly to connect them with mental health professionals who can help them heal. Organizations like the Children’s Bureau, a nonprofit that provides children with mental health care, are integral to Dr. Mukerjee’s care for her patients.

After the families are done telling their stories, we all go out to lunch. Sofia puts on my sunglasses and makes silly faces. Mateo and I talk about our favorite video games. Though their treatment is ongoing, the work the NOCHP is doing helps these kids grow up healthy, as any kid should. When we buy a red nose from Walgreens, we’re doing our part to help that healthy growth occur not just in New Orleans, but in cities all around the country.

Jim Kelly is a man who exudes love and kindness from the moment you meet him. This is probably because he’s had a lot of practice at it. As the executive director of Covenant House New Orleans, a shelter for homeless youth from ages 16–22, Kelly practices unconditional love for the 870 young people who seek food, clothing, and shelter. Red Nose Day funds not just Covenant House New Orleans but all of the Covenant Houses spread across North America.

Kelly doesn’t flinch as he rattles off the long list of issues that affect the residents: “Some run away, but most are thrown out of homes that don’t want them; some age out of the foster care system, or they come out of juvie or jail. ... Eighty-five percent of the kids [experience] PTSD or profound trauma. Thirty percent of our kids are on psychotropic meds. Eighty to ninety percent of our kids have been physically and/or sexually abused. A third are LGBTQ. Another third are young mothers.”

Kelly doesn’t provide care for the residents alone. The staff and volunteers at Covenant House New Orleans all share this passion for helping young people through crisis and back onto their feet. Their doors are open 24/7, and they will never turn a young person away.

When a resident comes to Covenant House, they receive a hot meal, clean clothes, a shower, a bed, and medical care. From there, the staff helps each young person come up with an individualized plan. That plan can include things like health care, individual and family counseling, social and legal services, job training and placement, educational assistance, and everyday life skills.

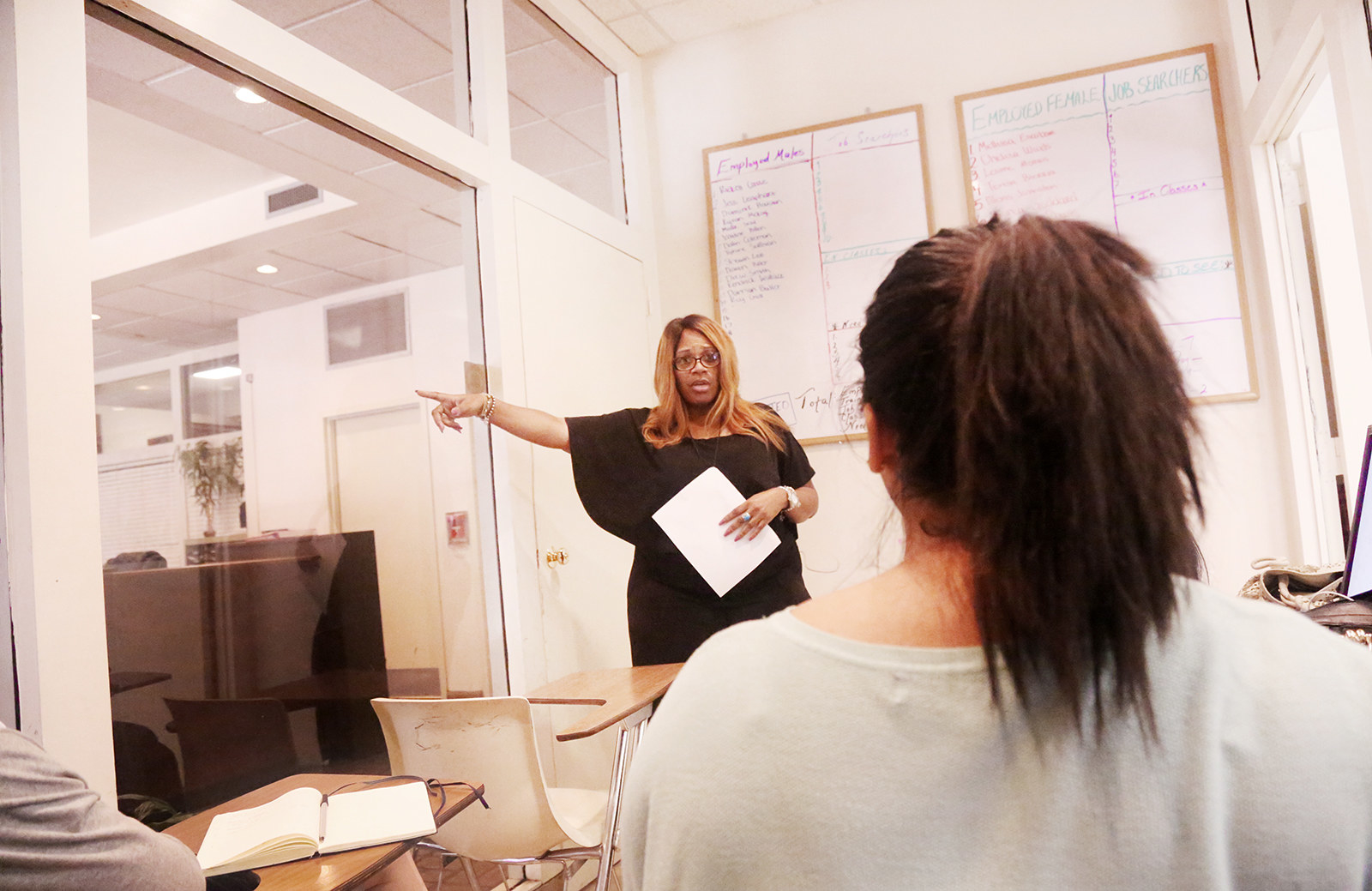

Some of those skills are obtained in Jane Helire’s classroom (Miss Jane, to the residents), where she teaches residents the skills they will need to obtain a job. Her lessons include how to access job-seeking websites, how to write a résumé, how to dress for an interview, and what to say during that interview. Miss Jane then sets them up with job interviews at local companies that partner with Covenant House to give residents a chance.

I ask Miss Jane if she has any success stories of residents who come back to visit her once they’re on her own, and she tells me this story:

“There was this young lady. She was here when I first started. Oh my gosh, she had a mouth on her. She just challenged you. If you told her, ‘The sky is blue,’ she’d say, ‘Well, why do you think the sky is blue? I don’t see blue.’ So we told her, ‘Girl, you need to go to school for law. You need to be a lawyer.’ She came back years later. She asked for me and Miss Archie [a well-known and well-loved caseworker]. She says, ‘I want to invite you guys to my swearing in.’ And we were like, ‘Swearing in?’ She says, ‘Yeah, I’m that lawyer now!’ So we go to the swearing in, and I’m sitting there crying, like it’s my own child.”

It’s evident in the young people I meet at Covenant House that their method of getting kids back on their feet is working. Armonn has been in the New Orleans area for about three years and at Covenant House for about a year and a half. He’s a cheery young man who responds to any request or question with a light and buoyant “most definitely!” His caseworker at Covenant House, Miss Foots, is famous for her brand of tough love. That tough love has taught Armonn pride in himself and in his work.

“Miss Foots cares about me when I don’t even care about myself. … She’s helped me find comfort in work, in the day-to-day grind. This is what I do. I know it’s forever. And I find comfort in what I do.”

These days, Armonn’s day-to-day grind is his work as a server on the Steamboat Natchez. If you’re ever in New Orleans, you would be lucky to have him as your server. Just get to him before he realizes his ambition of managing the whole boat.

Simon is another great example of how Covenant House helps young people grow. Simon is here at Covenant House because his mom kicked him out. Simon is also trans. I ask him if that’s the reason his mom made him leave.

“She says it’s not, but part of me thinks it is because she never supported it. She never acknowledged it.”

Simon’s relationship with his mom has always been strained. “I was never told that something I did was good after elementary school,” he says. “She always thought I could do better. I’ve never really been enough for her. Because of that, I’ve always had a low sense of self-worth.”

“There’s very little government funding, so we depend on the generosity of others. We depend on that person who buys a red nose.”

This is where the unconditional love shown by Covenant House can really make a difference. “They help us when we need it,” says Simon. “They do care, which I’ve never really had. So it means a lot to have this support system around.”

Simon now works as a silverware polisher at Brennan’s, a popular restaurant in the French Quarter. Simon is happy to have the gig. When we visit Simon at work, Kelly is sure to say, “Simon, I’m proud of you” before we leave.

Our visit teaches me that the staff at Covenant House does a tremendous amount of good, but Kelly reminds me that they can’t do their good work without a little bit of help from folks like you and me.

“Eighty-three percent of our money’s private,” he says. “Only 17% comes from the government. The only time the government wants my kids is to lock ’em up. There’s very little government funding, so we depend on the generosity of others. We depend on that person who buys a red nose.”

When I fly home from New Orleans, I am tired. The week visiting all the organizations that Red Nose Day funds in the city has left me exhausted — but also inspired. I’m left with a nagging sense that this is a very small sliver of the whole story. Remember, when you buy a nose from Walgreens, half of your donation goes to domestic work, like the kind we saw in New Orleans. However, Red Nose Day funds grants in all 50 states. I am exhausted from seeing just 1/50th of half of their work. I haven’t even seen the tip of the iceberg.

The other half of your Red Nose Day donations goes to 25 countries around the world. Our donations to Red Nose Day allows Save The Children to help prematurely born babies in Kenya. They help The Global Fund purchase and distribute medicine that prevents the transmission of HIV/AIDS from pregnant mothers to their babies in Haiti. They help the organization charity: water dig wells that provide clean water to schools and communities in Rwanda. This is just a small sampling of the opportunity you create for kids who are living in poverty in 50 states and 25 countries when you buy a Red Nose from Walgreens. But for this to really work, we have to do it together. Red Nose Day is May 25. Get everyone you know to join in, purchase noses from Walgreens, and put their noses on so we can all work together to end child poverty.

Photographs by Aubree Lennon, design by Lyla Ribot / © BuzzFeed 2017