‘Cut! And that’s a wrap!’ said the director of the documentary I was working on. This was the first film I wrote and worked on as an assistant director. The crew members and I researched and planned tirelessly for a year before we finally got to the shooting stage, travelling to distant places with breathtaking landscapes, chasing stories that need to be told. It was our last day. We quickly wrapped up the shoot, and hurried back to the hotel in elation of our achievement.

At the reception, we requested a bucket of hot water for each of our rooms. I eagerly awaited my bath and quickly dashed into the bathroom around half past eight at night.

A lone tubelight filled the bathroom with bright white. A small mirror rested atop a sink. I laid my sweaty, salty clothes aside, and pushed the bucket of hot water under the running tap. I swirled cold water into it with my hands and used a mug to pour it onto myself. Along with dirt, I washed away dried leaves and a few blades of grass that were caught on my skin and hair. I carefully soaped my body and when I got to my feet, I massaged my toes and heels. When I was finished, I dragged the water on the floor with my foot and swished it towards the drain.

I was done. I turned around to grab my towel.

A slew of questions settled in my gut: Who was he? How long did he watch? Did he have a camera?

In doing so, I happened to look up at the window on the wall that was placed just below the ceiling. The window was covered by only a flimsy wire mesh sheet. Through it, I saw a pair of eyes and a hand. The eyes, placed below a head of short, side-parted hair, watched me.

It was most definitely a man. We made eye contact for a split second. His right hand was trying to hold on to the window. In shock, I managed to let out a scream. Fumbling, heart pounding, I pulled the towel off the rack, threw it on myself to cover myself up haphazardly, and quickly unlatched the lock of the bathroom door and hurried out. I called my friend with whom I shared the room and somehow managed to convey what had happened while wailing uncontrollably.

As I sat on the hotel bed in my towel, perplexed and still dripping wet, a strange pang made me feel uneasy and squeamish. A slew of questions settled in my gut in that moment, which still live there: Who was he? How long did he watch? Did he have a phone? A camera? Did the sight of my unprotected, un-self-conscious body commit to anything more than his memory that day? Where does it live now?

In a matter of seconds, my autonomy over my body was taken from me. My right to decide who sees how much of it, when, how, where – all snatched away. It was an invasion into the intimate relationship I shared with my physical self, one that took years to build and cement. No belongings had been taken from me, yet I had been robbed.

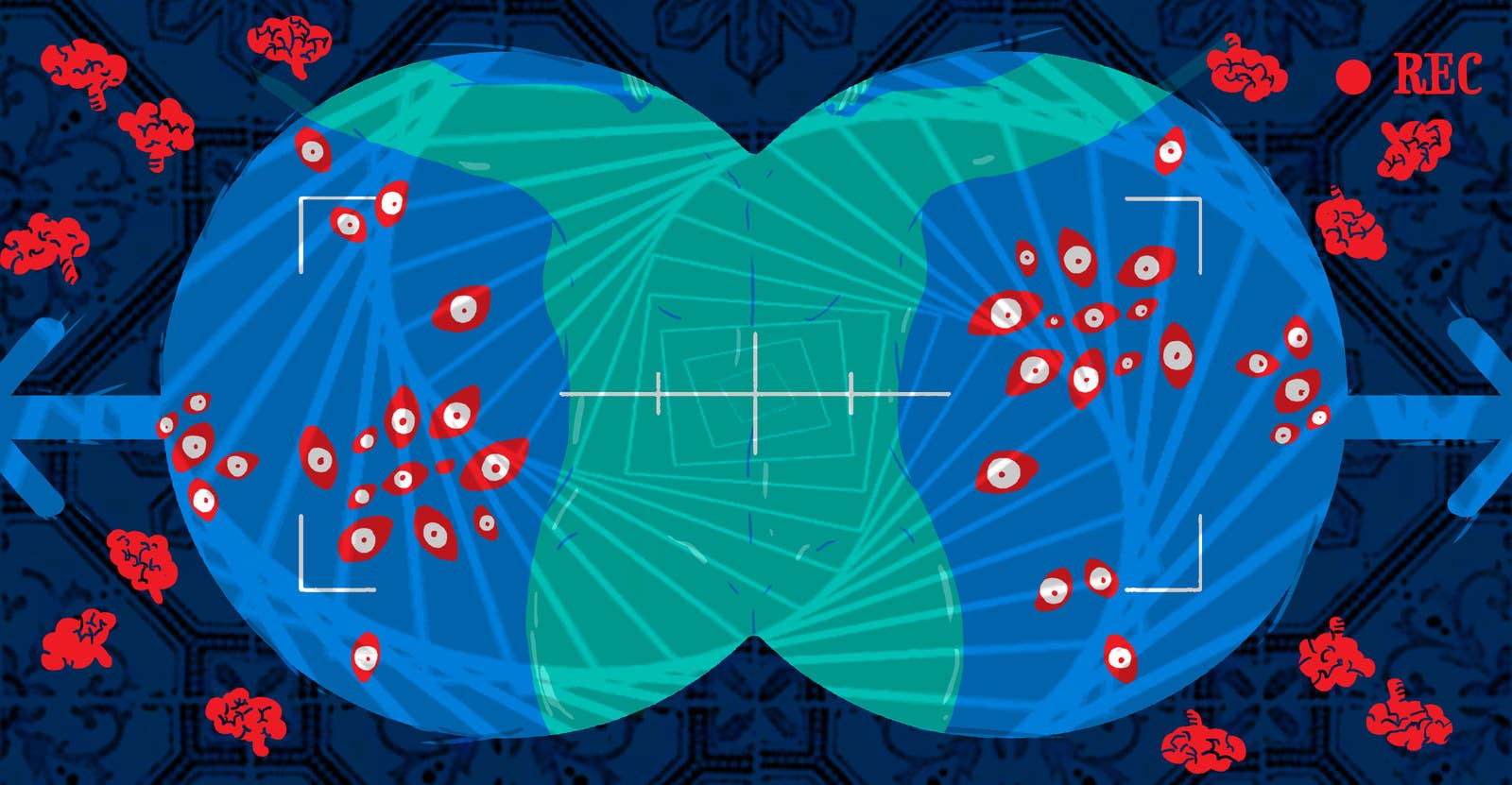

To this day, I am haunted by guilt and the fear that he clicked pictures or took videos. In an age where recording technology is advanced and easily accessible, it would only take a couple of seconds for such files to circulate around the internet and find their way to a porn website.

While mine was an extreme violation, the experience of being looked at and watched by a gaze you didn’t consent to is universal, especially among women. Especially among Indian women.

Sexual violations are not just limited to offenses that occur through touch. They include forms of eve-teasing like catcalls, stalking, sending unsolicited or obscene images or texts, exhibitionism and voyeurism. We get used to being looked at early in our lives. Stared at in public, ogled by men we didn’t give permission to, to sexualise us while we’re going about our daily lives.

No belongings had been taken from me, yet I had been robbed.

In India, voyeurism was criminalised as recently as 2013 under Section 354C of the Indian Penal Code (IPC). In the IPC, a voyeur is defined as ‘any man who watches, or captures the image of a woman engaging in a private act in circumstances where she would usually have the expectation of not being observed either by the perpetrator or by any other person at the behest of the perpetrator or disseminates such image shall be punished on first conviction with imprisonment of either description for a term which shall not be less than one year, but which may extend to three years, and shall also be liable to fine…’

Within an hour of the incident, I stood with my bags at the reception, waiting desperately to leave the hotel while also thinking about ways to officially record this incident. I couldn’t let it go. I decided to file an FIR. “Due process” would be followed. The perpetrator could be a part of the hotel staff, a guest or a peeping tom in the neighbourhood. An FIR, at the time, seemed like the best bet to ensure that this incident didn’t happen to others and that the hotel would be made accountable for its negligence.

As someone filing an FIR for the first time, I was unaware of how the experience of reporting a crime could add to my agony and cause further discomfort. Unable to hold back, my tears gushed out at different stages of filing the complaint; first while narrating the ordeal to the police officer, second while writing the incident down to form the FIR report and for a third time, when I handed over my report to a senior police official. It was excruciating and emotionally exhausting to live the pain over and over again.

I was unaware of how the experience of reporting a crime could add to my agony.

Sadly, this incident isn’t isolated by far. Recently, a student of Delhi University noticed a camera lens in her bathroom while she was bathing. In her case, the police were dismissive and kept reiterating that they couldn’t undo what’s done. Despite the complaint, they didn’t have any further updates on the perpetrator’s whereabouts in the investigation.

According to data provided by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), out of the total registered cases of crimes against women in India in 2015, 838 cases were of voyeurism. In 2016, the figure was 932. Out of this, 127 of these cases were filed in Maharashtra, 101 in West Bengal, 98 in Telangana, 93 in Madhya Pradesh, 92 in Uttar Pradesh, 83 in Andhra Pradesh and 43 in Delhi.

131 cases were filed in metropolitan cities with Delhi, Mumbai and Kolkata emerging as the top three. These incidents can occur at any place like changing rooms, toilets, public spaces, restaurants, schools and even in our homes.

Under the constant scrutiny of preying eyes, we also have to be wary of strangers clicking pictures without consent. In UK, girls as young as ten are victims of ‘upskirting’. It is defined as ‘taking intimate pictures underneath a victim’s clothes’ and has already been declared illegal in Scotland.

As public surveillance becomes the new norm, there is still a question mark on where all the information, data and footage lands up. In 2013, an Indian model was molested outside her apartment by her neighbour. A CCTV camera captured the incident as it took place. In a matter of minutes, this footage found its way online. Even today, a simple Google search of this incident will show numerous links where the footage can be viewed. No one knows who uploaded it. Was it even uploaded with the victim’s consent?

Closer to home, clicking and sharing pictures or videos without the person’s permission is not uncommon. The NCRB’s 2016 data also states that there were 957 cases filed under ‘publication/transmission of obscene/sexually explicit act, etc. in electronic form’. The number of cases filed in 2016 rose by 17.2 percent from the total cases filed in 2015.

However, fact sheets and data will never be able to record the unfathomable number of lecherous, scathing and intrusive glares that women, young children, queer and trans people are repeatedly subject to in public and private spaces.

But where does this voyeuristic behaviour stem from?

My childhood was filled with stories of Krishna, a mythical Hindu god. Growing up, I remember seeing colourful paintings and reading anecdotes about how he watched the gopis (his followers who were women) bathe in the river and would steal their clothes. For this, he was considered playful and even flirtatious; many stories even termed these acts as ‘divine’. But we must call it for what it is – a violation. An inappropriate, wrong and predatory violation. These stories are obviously fictitious and unreal, but they’ve also left a deep dent in many minds that’s responsible for normalising voyeurism.

I remember seeing colourful paintings of Krishna watching the gopis bathe in the river, and stealing their clothes.

The heroes of our mythologies inspire the heroes of our movies so Bollywood is more recently to blame for perpetuating such behaviour. Filmmakers, almost always male, are more like peeping toms with cameras. Meet-cutes are often replaced by the male protagonist enjoying long, lingering, lustful gazes at a woman just going about her daily business. In numerous films, the male protagonist or voyeur enjoys full freedom to letch at the body of women or stalk them to assert his feelings of ‘love’. Simultaneously, these films do not show the ‘love interest’ or woman give her consent to the man. It is often presumed that she has fallen in love with the male protagonist after he has concluded with his antics.

In the book Sex Offenders: Crime and Processing in the Criminal Justice System by academics Sean Maddan and Lynn Pazzani, it is suggested that voyeurism could be the gateway behaviour that leads to committing other sexual offenses. Furthermore, this book also derives from research which shows that most criminals convicted of sexual crimes have had a past history of voyeurism.

Space has a different meaning for me now. The onset of paranoia tears into every new experience. I don’t know if I feel safer in a room, with the windows and curtains shut, doors locked, or in a place where I can roam freely. I’m still a prey in both spaces.

Voyeurism could be the gateway behaviour that leads to committing other sexual offenses.

It’s been over a month since this incident and the subsequent FIR. The perpetrator still hasn’t been found. He vanished from that narrow space behind the window when I screamed in horror. It took him just a few seconds to run away free, without any consequences. But the burden of his actions fell upon me and I’m still trying to pull myself together and move forward.

As a young journalist, this episode in my life has taught me more about the uncertainty with which we put ourselves out there to report on fascinating stories and basically just do our job. We cannot control what happens to us but only learn from it and start a conversation around it.

When NCRB’s data for 2018 comes out, my complaint will be piled amongst a thousand other cases of various heinous crimes committed in India. But our experiences will be diminished to numbers. We are seen by others only as bodies, and we are seen by our protectors only as statistics. Behind the body, behind the statistic, a scared woman sits dripping through a towel, still wondering who her body is for, who gets to look at it, how to take it back.