Have you ever experienced the nagging suspicion that your partner is cheating, a gut feeling that something’s off, or a flash of maternal instinct? If you’re a woman who has, you might have chalked it up to women’s intuition — you know, the Spidey-esque ability of women to suss out others’ feelings. But according to journalist and author Rose Hackman (who has a master’s degree in Human Rights from Columbia University), there’s no such thing as women’s intuition. It’s actually what organizational psychologists call “subordinate’s intuition,” a form of emotional labor prevalent in unequal power dynamics where those in lower positions anticipate the needs of their superiors.

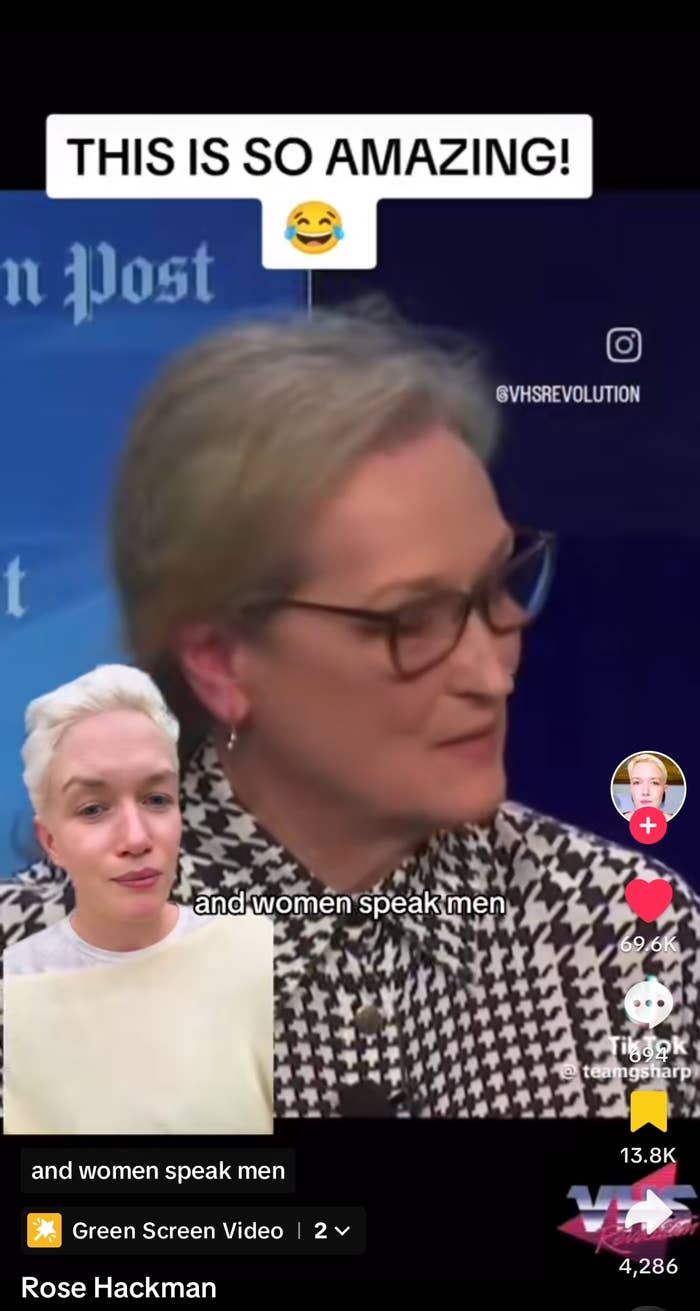

As Rose (@rose.hackman) explains in her viral TikTok — which has been viewed more than half a million times and garnered hundreds of comments — she was reminded of this fact after seeing a resurfaced clip of Meryl Streep speaking at a Washington Post panel. “It’s like women have learned the language of men [and] have lived in the houses of men all their lives,” Meryl says in the clip to The Post director Steven Spielberg and her three male castmates. “We can speak it… Women speak men, but men don’t speak women.”

“The punchline to this explanation, that is backed by research,” Rose says after the clip, “is at the very beginning of the Meryl Streep quote, where she talks about the fact that we have lived in men’s houses all our lives; that is what makes us so good at ‘women’s intuition.’ We have to be good at guessing the feelings and emotional experiences of the people around us because our livelihoods — our survival — depend on it. The fact that women are better at intuitiveness is tied to opposition.”

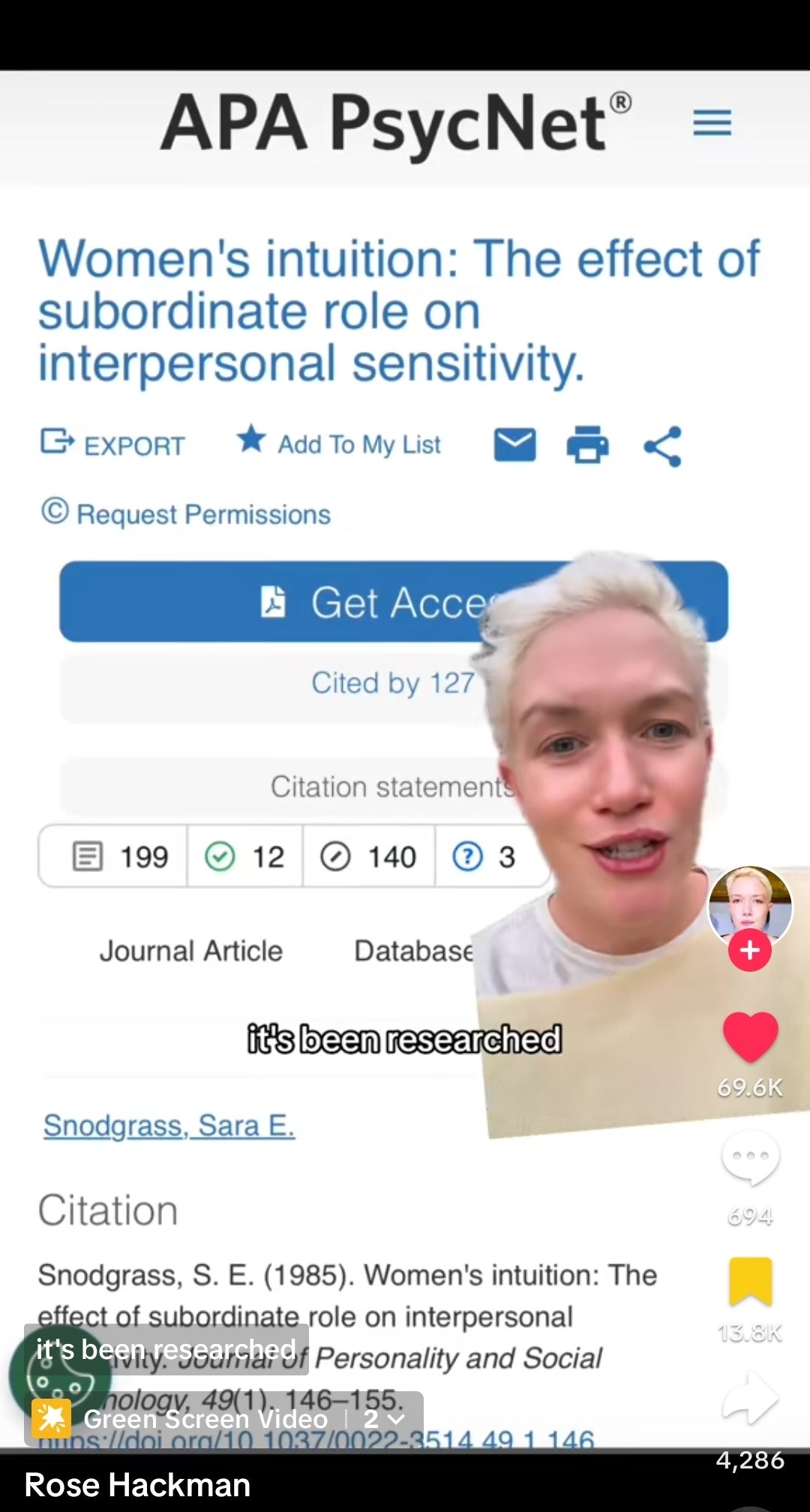

To back up her point, Rose shares a 1985 study that looked at the interactions between 36 pairs of undergraduate students. After randomly assigning one member to be the leader of the pair, the study found that those in subordinate roles showed higher sensitivity to the feelings of their leaders regardless of gender. This suggests that women, due to their historically subordinate status in patriarchal societies, may have developed greater interpersonal sensitivity than men, aka women’s intuition.

“It really finds that the norm is not women naturally being better at guessing what other people are going through,” Rose says. “The norm is actually a combination of leader expressiveness and subordinate perceptiveness. Male or female, a leader gets to express themselves unfiltered, and a subordinate is going to constantly be trying to perceive what that leader is trying to do, feel, express, [and] emote.” Women’s intuition is, therefore, not biological but rather a survival skill commonly observed in marginalized groups, and acknowledging that doesn’t mean it should be dismissed. Though it was developed out of necessity, Rose argues that women’s intuition is a valuable skill — one that those with privilege should especially embrace to dismantle discriminatory systems like racism, ableism, or anti-LGBTQ discrimination.

Though her TikTok is only three minutes and eight seconds long, it struck a chord with viewers across the internet. It even sparked discussions about subordinate’s intuition and its parallels in other hierarchical structures in the comments. “Reminds me of how Black people can code switch,” one viewer wrote. “People growing up in dangerous homes are better at it for survival,” said another. “Same thing as when you look at prey animals,” a top-voted comment read, “they know they’re vulnerable, so they’re ALWAYS on the alert.” One viewer even poignantly paraphrased a line from the novel The Silence of the Girls: “I didn’t watch him like a hawk; I watched him like a mouse.” That comment received more than 5,000 likes.

In a broader context, women’s intuition — or subordinate’s intuition in any social dynamic — represents a form of emotional labor, which involves managing other’s feelings and regulating emotional expressions during social interactions. Often, emotional labor, whether in person or professional settings, is associated with femininity and undervalued in society, perpetuating gender inequality and discrimination against women.

To explore the systemic framework of emotional labor, I spoke with Rose, whose book Emotional Labor delves into the concept and how it impacts our lives. In the book, Rose describes emotional labor as “the primordial training that, before anything else, women and girls should edit the expression of their emotions to accommodate and elevate the emotions of others.” For instance, women are told to smile more, mothers are expected to oversee every household detail, and young female professionals are passed over for promotions for being too aggressive. These examples, from the book’s front flap alone, offer just a glimpse at emotional labor and its impact on gender equality.

While Rose published Emotional Labor in 2023, the concept itself dates back to 1983, introduced by sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild in her seminal book, The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling, which highlighted shifting trends in the US economy. As the country’s services sector overtook manufacturing, Hochschild argued that emotional labor emerged as the predominant form of work. She drew upon the experiences of flight attendants to highlight that their role was less about serving food and more about creating an emotional experience that resonated with an airline’s image, whether it be care, comfort, or even sex appeal. Additionally, she emphasized that the cost of emotional labor is often unappreciated and undervalued.

More specifically, Hochschild delineated two main categories in her book: 1) Emotional labor, the paid emotional efforts within professional settings, and 2) emotion work, the unpaid emotional efforts in personal life. Consequently, emotion work is often perceived as feminized labor due to cultural norms expecting women to manage their emotions and those of others. This is compounded by the fact that, historically, women’s limited job opportunities led them to make a resource of emotions to compensate for their material lack.

As a result, sociologists have traditionally studied emotional labor separately from emotion work, but Rose asserts this over-complication only occurs in feminized labor: “We don’t say that cutting down a tree in paid versus unpaid settings should be called something else. You don’t say physical labor can’t be called physical labor if it’s not paid.” (Hochschild, whom Rose interviewed during her research, not only agreed with her stance but endorsed her book.) Ironically, this debate of remuneration goes back to the core question: What constitutes ‘real’ work?

By societal standards, real work is often defined as being paid. If it’s unpaid, it’s not real work. However, this perpetuates the devaluation and invisibility of unpaid work often assigned to marginalized groups, from emotional labor to slave labor. “It has served to obscure the very real work of not just women in this country but of Black people and minority groups, who very often have either not been paid for the essential labor they’ve contributed or been drastically underpaid and worked in horrible labor conditions,” Rose said.

To better recognize emotional labor, imagine its absence in paid settings: An impatient teacher who is rude to her students; a nurse who is apathetic and short with her patients; a customer service representative who is unhelpful and condescending to her customers. If these professionals didn’t perform emotional labor, the foundational quality of their roles would collapse, stressing that emotional labor is far from invisible when it’s necessary. Despite its crucial role, many professionals receive pushback (“That’s not real work.”) when discussing emotional labor, primarily due to societal biases against tasks considered feminized and privatized, which disproportionately burden women.

In fact, Rose originally dismissed the significance of emotional labor herself when she was first assigned the topic as a features writer at the Guardian in 2015. With her background in human rights and journalism focused on structural inequality, she feared she’d be pigeonholed as a “privileged, white women’s issues reporter” for covering the topic. However, her research soon revealed the broader implications of emotional labor in shaping socioeconomic structures and perpetuating societal inequalities. This led her to question who is responsible for managing others’ emotions, who is expected to invest time in ensuring others feel good, and who is viewed as subordinate in society.

For her 2015 Guardian article on emotional labor, Rose spoke with Jennifer Lena, a sociologist and professor of arts administration at Columbia University, who told her, “The way I think of emotional labor goes as follows: There are certain jobs where it’s a requirement, where there is no training provided, and where there’s a positive bias towards certain people — women — doing it. It’s also the kind of work that is denigrated by society at large.”

To illustrate that, Rose pointed to tipping culture in the US. Tipped employees, defined as those earning over $30.00 monthly in tips, are subject to a federal minimum wage of $2.13 per hour. Though certain states have set higher minimums, the national average remains below $6.00 per hour. As a result, tipped employees are required to do emotional labor without compensation and rely on customers — who expect emotional satisfaction — to recognize their efforts through tipping.

This not only leaves tipped workers vulnerable to the preferences of customers but also disproportionately impacts women, who make up about two-thirds of tipped employees in the US. Rose underscored this disparity with a 2018 study, which found that women in states with a $2.13 minimum tipped wage experienced sexual harassment twice as often and pressure to dress “sexier” three times as often as those in states with higher minimums.

In a broader sense, the issues and gendered biases within tipping culture reflect larger systemic obstacles for marginalized groups at work. As workplaces evolve to be more inclusive, discrimination linked to emotional labor becomes increasingly evident. Women encountering historical barriers confront a multitude of stereotypes, spanning from being deemed bossy to facing accusations of sleeping their way to the top. Unlike men who often advance by demonstrating competence and confidence, women must balance these traits with expected displays of empathy and other-oriented behavior. Yet, this balancing act is fraught with risks: Those who exhibit too much emotional labor risk being seen as pushovers or inauthentic, while those who show too little face criticism as well.

Rose exemplified this with the viral 2010 TED Talk by Lean In co-author and former Meta chief operating officer Sheryl Sandberg, which urged women to demand a place at the table. Despite its initial positive reception, Sandberg’s stance later faced criticism for oversimplifying individual agency and neglecting systemic biases. These biases include the “backlash effect,” wherein women and men of color are penalized for exercising confidence and assertiveness, often seen as “counter-stereotypical behaviors.”

These double standards around emotional labor also extend to aesthetic labor, in which women are expected to make others feel good by conforming to the feminine beauty ideal. In Hillary Clinton’s 2020 Hulu documentary, the former 2016 Democratic presidential nominee disclosed she spent an hour to an hour and a half doing hair and makeup every morning during the 600-day presidential campaign. “I calculated it, and I spent 25 days doing hair and makeup,” she explains. “I knew that the man I was running against didn’t have to do any of that.” As Clinton’s campaign highlights, women — from tipped employees to political candidates — must invest endless hours in aesthetic labor to meet strict beauty standards, effectively exchanging their time for access to certain spaces.

Given that women (and men of color) are expected to navigate these unspoken obligations on top of their actual job responsibilities, the idea that they can just emulate white men for career success ignores the discriminatory double standards around emotional labor. At a systemic level, this obligatory emotional labor — which requires effort, skill, and time to perform — upholds power structures, reinforcing the subordinate status of marginalized groups. “When you’re expecting some groups to perform a whole extra shift at work that is uncompensated, it’s really about performing subordinate status.” Rose commented. “That’s part of how we ‘keep’ women and marginalized groups ‘in place,’ by holding them to separate standards where the entry fee is performing all of this other-oriented emotional labor.”

While often treated as isolated incidents, gender discrimination and inequality thrive on systemic roots like the invisible burden of emotional labor. From the fact that female CEOs run roughly 10% of Fortune 500 companies to the fact that more than 30% of single-mother families live below the poverty line, it’s evident that the disproportionate distribution of emotional labor places significant barriers for women’s advancement. Feminized jobs requiring significant emotional labor, like caregivers and teachers, are also undervalued and underpaid, contributing to the feminization of poverty. Despite this, many believe women have achieved gender equality and personal agency thanks to their presumed freedom to make choices. However, this overlooks the systemic barriers limiting their options and the consequences women face for rejecting emotional labor, further perpetuating gender discrimination.

(Also see: choice feminism.)

To that end, Rose asserts that the next wave of feminism hinges on acknowledging and appreciating emotional labor through an intersectional approach. Though it disproportionately affects women, emotional labor is rooted in larger societal structures that devalue anything associated with the feminine. Accordingly, “feminine” skills, like nurturing and caretaking, are devalued and relegated to subordinate roles. This systemic bias perpetuates the view of emotional labor as “women’s work.” As a result, emotional labor is undervalued and those performing it are assigned lowered status regardless of gender.

This systemic bias becomes glaring when compared to labor movements, which have historically focused on traditionally masculine industries. For instance, male factory workers in manufacturing receive recognition for their efforts to secure higher wages and improve working conditions. Meanwhile, the unseen emotional labor of women — crucial for nurturing families and stable homes — remains undervalued. Therefore, Rose argues, the scope of worker rights must be expanded to appreciate emotional labor alongside other forms of labor. This is crucial for creating fair and sustainable labor models that benefit everyone, especially women and marginalized groups.

In particular, Rose traces the devaluation of emotional labor back to second-wave feminism for overlooking emotional labor while advocating for women’s entry into the workforce in the 1960s. Though financial independence is vital for empowerment in capitalist societies, women entering the workforce didn’t lessen their burden of emotional labor. Instead, it led to its undervaluation in paid settings, creating a dilemma for women juggling full-time careers and motherhood — a dilemma women still face today. But without women’s continued performance of emotional labor, in both at home and work, economies would collapse.

If that seems difficult to imagine, look no further than the 1975 Icelandic women’s strike, known as “The Long Friday.” Frustrated by unequal pay, job obstacles due to childcare duties, and overwhelming housework, 90% of Icelandic women went on strike. They abstained from work and domestic chores to underscore their indispensable role in sustaining Icelandic society. Though it lasted just one day, the strike paralyzed the nation’s economy and public life. Schools closed, flights were grounded, and newspapers ceased production. Within a year of the strike, Iceland enacted laws guaranteeing equal pay and promoting gender equality in politics and economics. Nearly 50 years later, this groundbreaking strike continues to stand as an iconic emblem of collective feminist action.

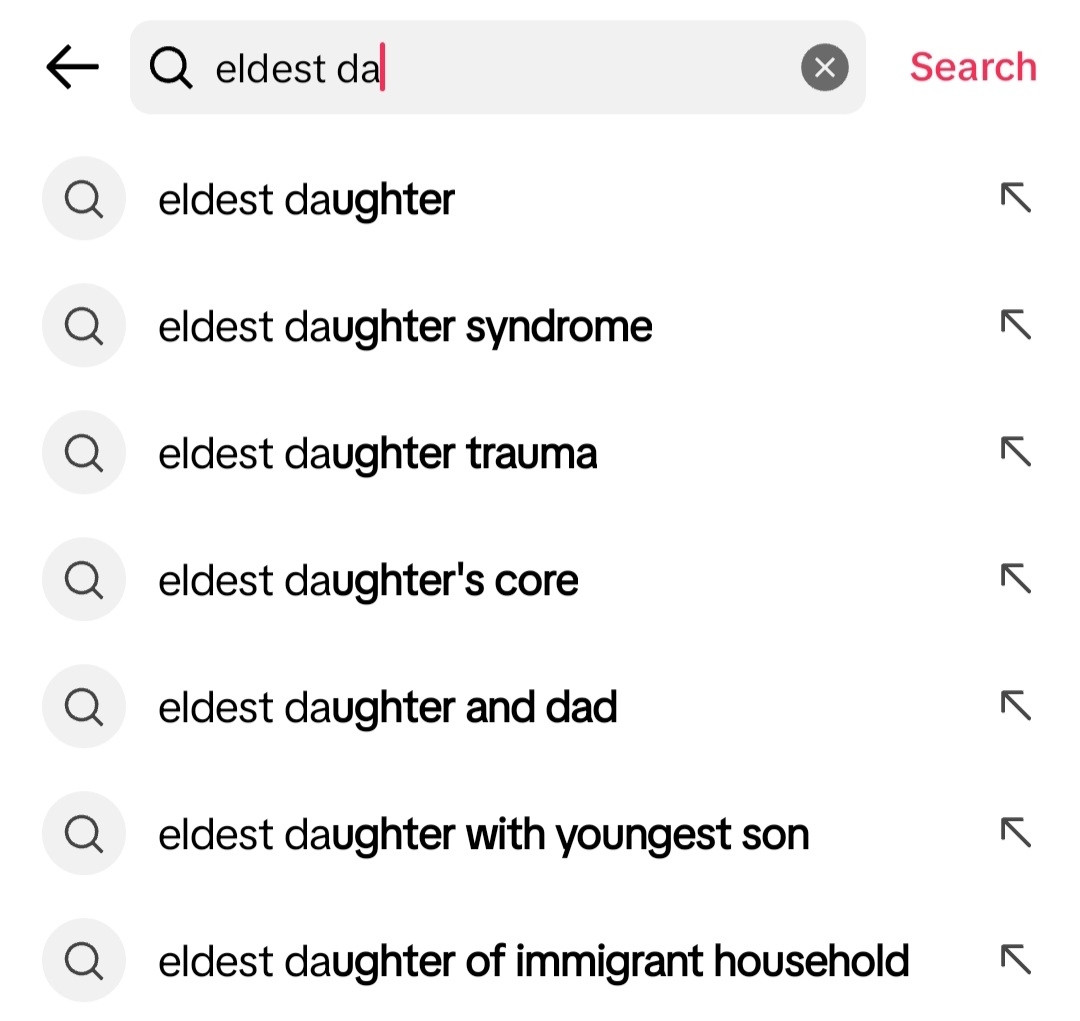

While there haven’t been recent strikes of the same scale in the US, there’s been a rising awareness of emotional labor as evident on social media — even if not in academic terms. A quick glimpse at TikTok alone reveals women voicing their struggles through various trends: people pleasers, eldest daughters (especially of immigrant families), burnt-out gifted kids (specifically related to the gender gap in ADHD and autism diagnoses), daughters of fathers with anger issues, and wives making detailed grocery lists for their husbands (leading to conversations about weaponized incompetence and the mental load). Collectively, these discussions reveal an ingrained acceptance of caregiving roles in women and signal a deeper, systemic issue. At the same time, they’re sparking counter-trends that inspire a revaluation of emotional labor and encourage women to place their emotional needs first.

In her research, Rose also observed a common childhood pattern among women: walking on eggshells when their father came home to avoid provoking his anger. These early experiences often taught women to anticipate and adapt to men’s moods out of fear. Tragically, this behavior often persists into adulthood, with some women facing intimate partner violence — a grim reality reflected in crime statistics. US crime reports reveal that over half of female homicide victims are killed by a current or former male partner, and one in three women experience violence or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime. On an existential level, beyond workplace dynamics, emotional labor develops as a survival tactic, as exemplified by women’s intuition.

More broadly, the normalization of performing emotional labor for safety perpetuates societal power structures. As Rose pointed out, when those in power allow themselves to be dangerous, those with less power must constantly adapt to their behavior. In the context of abusive relationships, victims frequently bear the brunt of managing an abuser’s erratic emotions; yet emotional challenges are often disregarded as feminine issues, despite their widespread recognition, even by men, and their potential severity.

Nevertheless, as women gain independence and become more selective in relationships, some men have adopted radical ideologies, exemplified by movements like the Red Pill and figures like Andrew Tate. According to Rose, these attitudes represent a resistance to changing gender dynamics. Similarly, there’s been a growing gender gap in US politics, with more young women leaning liberal and more young men embracing conservatism. Ultimately, these cultural shifts emphasize the significance of emotional labor in shaping gender and power dynamics.

An ardent feminist and advocate for valuing emotional labor, Rose is no stranger to the backlash that comes with challenging deeply ingrained societal norms. Men from both ends of the political spectrum have pushed back against her work, albeit in different ways. On the one side, conservative men tend to dismiss and even mock emotional labor, while on the other side, progressive men often display condescension under the guise of concern — a form of intellectual sexism rather than overt misogyny, Rose wryly noted.

Case in point, Rose once faced criticism from a male author who disagreed with her views on emotional labor, despite quoting her Guardian article in his newsletter. When she offered him a copy of her book, he replied: “Oh, I actually have a copy of your book. Your publisher sent me one when it first came out, I really ought to get around to reading it.” He then asserted that emotional labor isn’t real work because it lacks the framework for protest and organization. Unfortunately, this type of opposition is common for Rose, with some self-proclaimed progressive men labeling her stance as “neoliberal” or “hypercapitalist,” and even suggesting that emotional labor should “rise above” capitalism. “By the way,” Rose added, “I don’t think all emotional labor should be paid.” Alternatively, emotional labor can be validated through reciprocity, status, recognition programs, and other means.

However, Rose acknowledges that not all men are dismissive of the value of emotional labor. A number acknowledge its universal benefits, understanding that suppressing men’s emotions harms both individuals and society. As an example, Rose pointed to the male loneliness epidemic, emphasizing that emotional intelligence and labor are essential to well-being and fostering connections. She also called out situations where women, especially women of color, are expected to address men’s emotional needs neglected by society, like veterans struggling with civilian life or formerly incarcerated men reintegrating into society.

To explore this further, Rose dedicated a chapter in her book to the consequences of undervaluing emotional labor on men, aptly titled “What about the men?”

From Meryl Streep’s comments and Rose’s viral TikTok to social media trends and indisputable statistics, it’s clear there’s a growing awareness of emotional labor's systemic undervaluation and widespread impact on individuals and society. And like Rose’s work reveals, acknowledging and valuing emotional labor is a crucial first step toward addressing collective social issues.

Despite the inevitable pushback, the increasing dialogue around emotional labor signals a willingness to reconsider traditional gender norms and social structures. As seen in the 1975 Icelandic women’s strike, refusing to perform emotional labor can be a powerful form of protest — one that demands recognition and change. On the other hand, embracing emotional labor can transform it from a discriminatory burden to a shared strength, fostering a more equitable society.

Ultimately, Rose believes there’s profound power in acknowledging and valuing the emotional labor in our lives. Through her work, she aims to inspire others to rethink traditional narratives around emotional labor, like women’s intuition, and consider its broader implications. “My time is not like eternal sand, and your time is an hourglass,” she reflected. “Our time and work is worth the same. But value is not just about measuring it in terms of time.”