As someone who is mixed-race, I've noticed some interest in mixed-race families. Sometimes, it's shallow fascination or ignorant (and intrusive) questions. Other times, there's a genuine curiosity about what it's like and what people should understand about the mixed-race identity.

To better platform the nuance of the mixed identity and the mixed family, I asked people in the BuzzFeed Community to share their observations and experiences growing up mixed-race. Here are 26 of their stories:

1. "There's not always a culture clash — not in my family. The labels of white and Black didn't exist. It's probably because my parents and family came from the same place, Belize. So despite their skin colors, they all loved the same food, music, and having a good time."

2. "Both sides of my family hate each other and have no contact. I'm also the only mixed person in my entire family, as everyone else is either Black or West Indian."

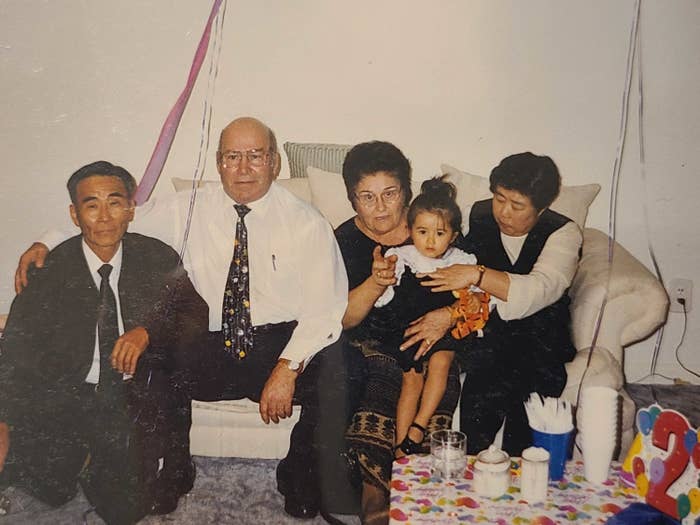

3. "Many times, I've had people mistake my white, biological father for my husband (I'm Filipino, Scotch, and Irish). I'm not ashamed of my dad — he's the best human being I know — but I also don't want people making gross assumptions about us. When we're out in public, I say 'dad' much more than I probably should. Numerous people have also told me about how terrible white people are because of racism and white privilege, and it breaks my heart. As I said, my dad is one of the best people I know. He's honest to a fault, works hard, has provided for our family our entire lives, and has accepted my mother's culture to the point where he's collecting antiques from the Philippines."

"I think the phrase, 'Don't judge a book based on its cover,' should apply to everyone."

—Anonymous

4. "Growing up, I was an ambiguous, light brown kid with an odd last name that no one could pronounce. I wish I could speak both languages fluently, but my parents wanted me to feel integrated in my neighborhood and school. My mother is a first-generation Texan from Mexico, and my dad was born in Iran. Regarding religion, my mom tried to raise us Catholic, and my dad came from a Muslim background and never converted. In the end, my sister and I didn't get the whole religion thing; we just got into being good, moral people. It's worked for me so far, but I've been dating a guy with severely traditional Muslim parents, and they disagree with my interfaith upbringing. I'm the product of love over religion, and I've got to say, seeing how his family is, I don't want it any other way."

5. "Your kids will notice if your spouse's family mistreats you or is racist. My dad immigrated to the US as a teenager and immediately joined the military to fast-track his citizenship. He met my mom through a friend in the military, and the rest is history. He was the first in his family to marry out of his race and the second to reject an arranged marriage. His parents were furious with him and took it out on my mom for most of my childhood. My aunts and uncles were no better, constantly sniping at my mom about her weight or talking about her in Hindi when she was in the same room. They were not unkind to us kids, but it affects you when you see someone making your mom cry, and no one is doing anything about it."

"If your family is like this, think about if you want your kids to be around that. Even though you might think it's just adult stuff, the kids notice."

—Liz, 38

6. "One thing I don't see people talk about much is having completely different experiences from your siblings. You can look completely different from them, and you'll witness how it impacts your lives as you grow older. It can forge your bond or create resentment. For me, it's done both. I have good relationships with both of my siblings today. Still, I've had several conversations with my white-passing, heterosexual brother about why he might not understand certain things. Each of you might closely identify with one ethnicity or culture more than the other. I think our differences make us unique and stronger, but I say that now as an adult. Growing up, it was sometimes tough to relate to your own family while at the same time not."

7. "My mom is white, and my dad is Black. My mom had no idea how to handle my hair — I have very curly and big hair — so she would treat it like straight hair. Now, I have very unhealthy hair. I also got many weird looks whenever I was out with my mother. People couldn't grasp the concept of a white woman having a Black child."

"Otherwise, there are always subtle slights from both sides of the family — but mainly from my mom's side, from the hair touching to dirty looks and the use of the 'n-word' around me since I'm 'only half Black.'

Overall, I always had trouble with my racial identity. I'd always feel like I never belonged; I was always too light-skinned or too tan. I love my family very much, but they don't understand how hard it can be sometimes. I always feel left out."

8. "From a very young age, I learned to try to blend in because we always stuck out. I was also very resentful of my Indian heritage because it made me feel so 'other' rather than making me feel like I belonged. I wouldn't change my parents, but I wish I could be one race to belong somewhere. It's exhausting to explain how I exist whenever people ask, 'What are you?' Refusing to engage only prompts more questions. I then feel conflicted about how to raise my kids. They're unidentified white, German, Japanese, and Indian but present as white. Do I teach them about our various heritages, though they caused me pain? Is it appropriate if they celebrate Diwali since they look white? Is it disrespectful to let them pass so their lives will be less difficult? Is that cheating them of important experiences? Are we at a point in society where race is more than just fitting into a box on a government form? Am I destined to belong anywhere?"

"The feeling of not belonging anywhere never ends. My grandfather was a priest, so we went to many religious functions. My mom, sister, and I never knew what we should do and always felt like we stuck out. My dad did not care at all. I don't know if it was because he didn't want to be there either or if he thought religion was silly, but he made no effort to tell us what would happen or how we should act.

Decades later, much of that hate is gone — mainly because my mom devoted her retirement to caring for my grandparents. But truthfully, I'm still not over it. I still feel panicked when I think of having to see family during the holidays because I've been conditioned to believe that it will be miserable.

I don't have any connection to my Indian heritage. I wish I did, but I'm too scared of being hurt to try to learn. I have an aunt and uncle that I have cut out of my life entirely because they treated us the worst, even though I've heard they have softened up in their old age."

—Liz, 38

9. "If you have mixed kids, I urge you not to raise them in a colorblind household or lie to them about their heritage. You might think it doesn't matter and write it off as 'identity politics,' but that can lead to confusion, resentment, and therapy co-pays. I'm a mixed woman who grew up in a colorblind family. My mother's family is Western European, and they were my primary family growing up, as my dad is estranged from his. We never discussed race; whiteness was the default, and my siblings and I looked ambiguous, if not white-passing. Whenever I asked my father about our background, he lied or insisted it didn't matter. Since my parents viewed race as unimportant, I had to do a lot of identity work on my own to answer awkward questions from strangers. I only learned the whole truth about our heritage in my 20s. As an adult, I feel a deep sense of loss because I grew up disconnected from the Black community."

"One of my father's relatives contacted me on Facebook, and I learned that my father comes from a long line of mixed Black folks dating back to enslavement in the US. Our last name comes from a white slave owner who had a second family with an enslaved woman."

—Mel, 34

10. "You're half of two things, which is great because you get twice the cultural exposure, but in my experience, you also never feel whole. I attended an international school that would spend an entire semester planning an annual event called the Global Picnic. You were supposed to form a country-based group with others from your heritage to organize food and a performance for the event. I never knew where to go. I didn't speak the language of either group and never lived in either country. It was very isolating. I ended up sneaking into the USA group. Everyone there spoke English, and we just talked about TV."

11. "I grew up in California with my Hawaiian mom and Euro-mutt dad (he's mostly Norwegian, Irish, and English). They met during a rival high school football game in the '70s. My mom's side of the family has dark brown eyes and Polynesian hair. However, my siblings and I came out white as snow and with my dad's blue eyes. My dad didn't know his culture, so I grew up with Hawaiian traditions, foods, and folklore. My grandma spoke pidgin and Hawaiian, and we had rice with everything. But both sides of my family still rejected us — my mom's side specifically because we were 'too white.' I was so excited to live in Hawaii for a time, but I was never included in anything because I was just 'another white girl trying too hard.' As an adult, I'm now a proud hapa, but never knowing where to fit in hurt as a kid."

"Because I never looked hapa, I was an outcast as a kid. I could speak decent Hawaiian and pidgin — but they hated that and hated mainlanders even more. I was a damn kid and told to shut up.

As a teen, I just gave up telling people, not because I was ashamed but because keeping up with everyone and their questions was exhausting. I still speak Hawaiian with my grandma and have taken up dance again, but it took a long time to return to my roots without feeling like I didn't belong to either side."

12. "The biggest thing is growing up thinking your family structure is 'normal' because it's all you know, and then stepping into the outside world and being told by extended family, strangers, and media where you do and don't belong. You get microaggressions, subliminal hints, or even overt comments. Even when people mean no harm, it still makes you feel some type of way. For example, I recently went shopping with my mother, and the cashier put a plastic bar between our stuff. I laughed, hugged my mom, and said, 'No. I'm with her.' It's an innocent misunderstanding but still communicates that we do not look alike."

13. "My mom is Mexican and darker; my dad is white. If I could give people any advice, it would be to mind your business. You are not entitled to know the family origins of a stranger. It's also not okay to invade a family's personal space and accuse them of dishonesty because they don't look how you think they should. Families come in all different ways, and they are all valid. Growing up in California, my family was often approached by invasive strangers who assumed that my mom was my nanny and asked things like, 'Do they have the same dad?'"

"It's also super racist to 'compliment' Brown people for their lighter-skinned kids. It's 2022, people. Keep that colorist shit to yourselves."

14. "I'm white, and my partner is Black. It'd be really nice if people stopped assuming my kids don't have a dad or asking if my kids have the same dad."

—Anonymous

15. "I have white-passing privilege, and this is something I've realized years later. I don't really look like either of my parents — although some say otherwise — and I never fit in on either side. Because I look more white, I assimilated with my white peers and sometimes felt more English than Malaysian Chinese. I definitely ate a lot of cooked breakfasts, but I never related to my Asian side as much. However, when I hear people's stories of oppression, I feel guilty for feeling like I don't completely fit in. Now, I'm trying to connect with my Asian side by learning Mandarin and embracing the culture."

"The one question that's frustrated me for years is, 'Where are you from?' I've gotten so fed up that I just say, 'London,' and refuse to say anything else. My partner is darker and wasn't born in the UK, so he often has to tell his mixed heritage.

I also hate when I get asked where my parents are from. People treat it like they've won the lottery."

—Anonymous, 30, London

16. "I'm mixed Native — Cherokee, Lakota, and white — but I'm mostly Native. My birth dad skipped out before I was born, and my mom grew up in a Catholic orphanage. My older half-brother's family, who are white, ended up adopting me. There was very little racism for the most part, and they tried hard to help me connect with my Native side while living in an all-white town. However, I was constantly made to perm my 'typical' Native hair, which is nearly black and stick straight. Now, I'm in my late 40s and still coming to terms with the paleness of my skin and my inability to 'pass' blood quantum. The Native community is generally tight-knit and unwilling to let outsiders in unless you can prove yourself — rightly so, but it still sucks for those of us adopted by white folks."

"Between ages 10 and 18, I'd only met three people of color, including a Black man who hid his racial identity to avoid being hurt. Though I'm paler, I was the darkest person in school. That messes with your head a bit; it's a lot of internalized racism to work through as you get older.

As for my hair, I got to my 20s before I decided not to keep perming it. The funny thing is that it's started curling on its own now. It's actually starting to look like my birth mom's hair, but I have no idea how or why."

17. "Growing up, my white mom was the one trying to teach me about my Chinese heritage. It was through little things, like giving me red envelopes on Lunar New Year and reminding me of my Chinese name (given to me by my dad's parents). My dad wasn't interested in teaching me because he grew up being othered and feeling isolated for being Chinese. He also isn't close to his side of the family. However, that's not to say he taught me to be ashamed of being Asian."

18. "My mother is from the Philippines, and my father was a white American. At times, it wasn't easy growing up. I never fully felt like I belonged to my white side. My grandma also favored my full-white cousins and used racial slurs. Some of them would even make racist jokes like, 'Does your mom's family eat dogs?' My dad never put up with any of that when he was alive. It was hard. Now, I don't put up with any of that as an adult, and no one says anything remotely close to that anymore."

19. "My dad is Black and Native American, and my mom is white. My two sisters and I have tan skin, brown eyes, and dark hair. However, we all have different hair types, ranging from straight to curly. I was 15 when I finally figured out how to do my hair. In middle school, I had an identity crisis. The white kids kind of accepted me but would make racist jokes. Some of them were also bullies. On the other hand, the Black kids didn't accept me unless I talked and acted like them. Finally, I broke away and started hanging out with nice girls, and I was finally happy."

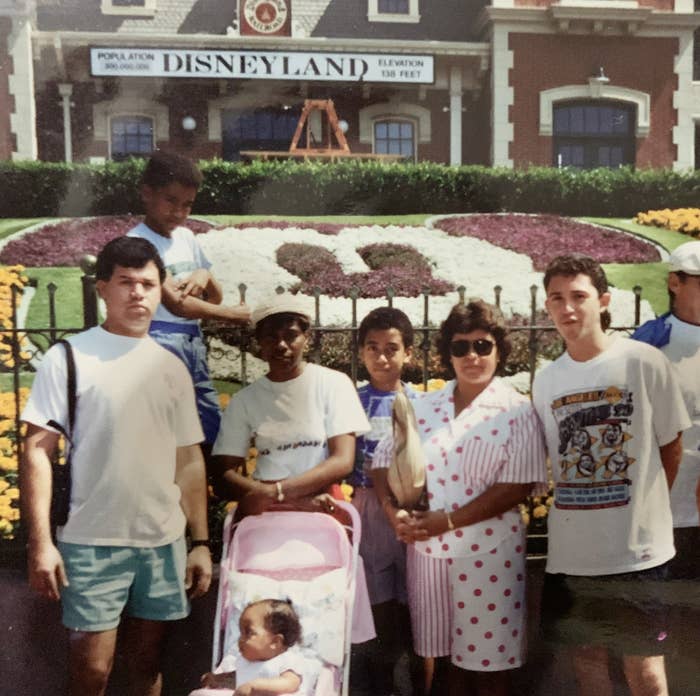

"My mom used to joke that people would think she kidnapped us because she's white and blonde. Strangers in public were always really kind and gave compliments to my mom about how cute we were. But around my dad, they would be cold, ignore all of us, and give dirty looks to my parents (this was in the '90s).

My mom's parents also initially didn't like my dad and were racist. But as they got to know him and his side of the family, my maternal grandpa found that he really liked my dad, and my maternal grandma (who came from Germany as a young child) fell in love with Native American culture."

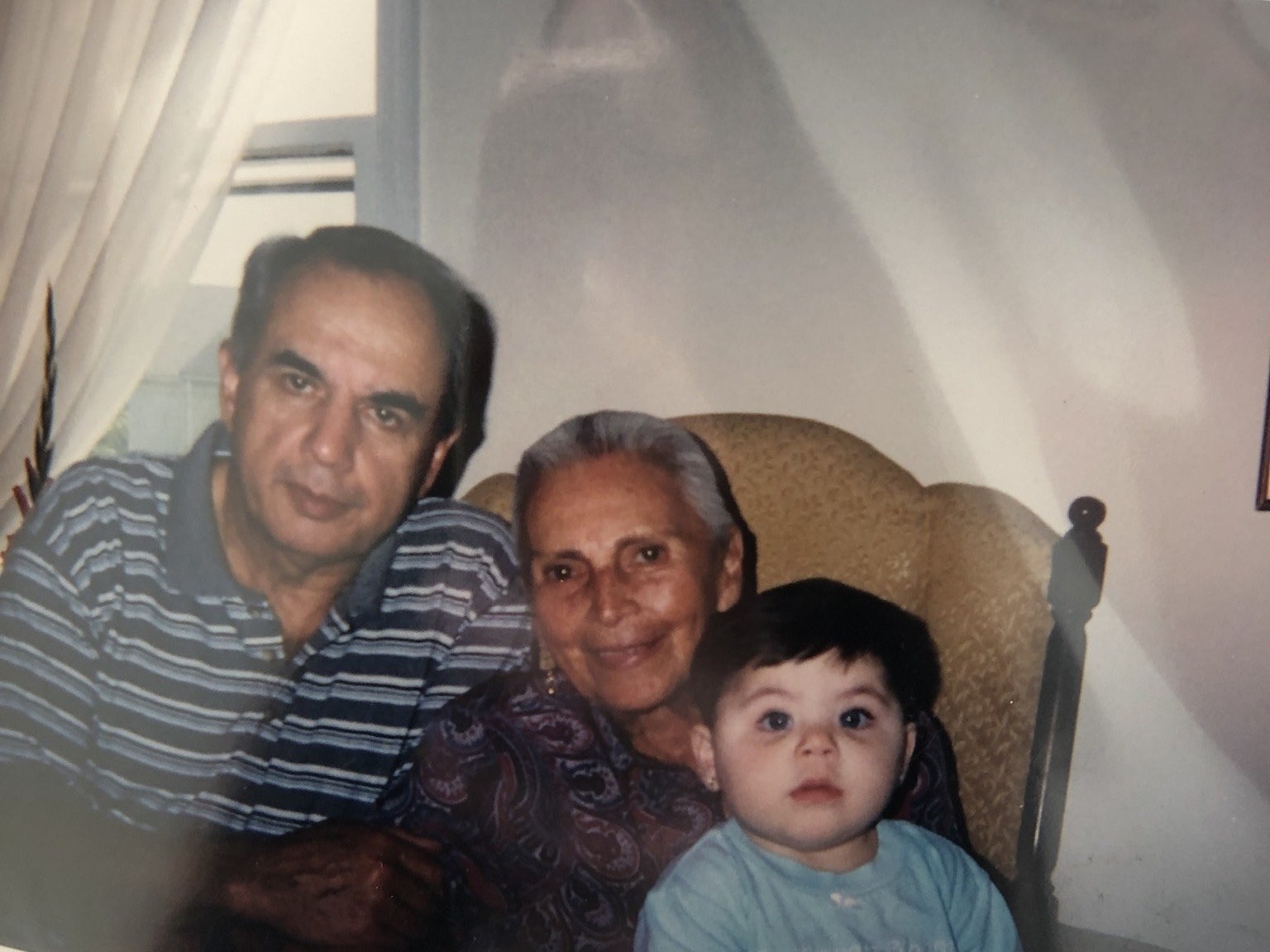

20. "Being Colombian and Persian, I was always asked how I looked the way I do and why I'm not 'tan.' Genetics are weird, people. TSA would also stop me and my grandpa at the airport because they thought I was being kidnapped to Colombia. Another thing: People like to ask about my family history and why I speak Spanish but not Farsi. Ma'am, this is a Starbucks. I'm just trying to get my drink, not do a bit on generational trauma."

21. "My dad immigrated from Iran, and my mother's family has lived in the US for multiple generations. I don't speak Farsi, but when people realize I'm Persian, they always ask me if I do, and I feel like a fake. I also struggle with knowing how to define myself. As a white-passing woman with some ethnic features, I've never known what box to check or which culture I belong to."

22. "I'm half Chicana with white and Indigenous heritage and don't speak Spanish. Mixed folks are just not defined the way society likes to define race and ethnicity. The problem for me was never really that I didn't know how I saw my identity but more so how others saw it."

23. "My mother is Samoan, Tokelauan, German, and many other ethnicities (including French and Cook Islander Maori). My father is Filipino, specifically Ilocano, from the Pangasinan region of the Philippines. I grew up in Hawaii, where being 'mixed race' meant existing and navigating multiple ethnic identities and cultural contexts. When I moved to the mainland, I found it wild that people could not fathom that being 'mixed race' could mean identifying with more than two ethnic identities. There was always this push to simplify and reduce my identity because I had 'one too many backgrounds,' which was abnormal. It's like having multiple ethnic identities was completely absent from Western cognition and hard for people to grasp. In general, the US has backward misconceptions of race and ethnicity. Frankly, it's exhausting to qualify, educate, and explain myself constantly."

24. "I'm Black and white. My mom couldn't deal with my hair when I was a child, so she would keep it short. When I was 10, I refused to cut it and started growing it out, but my mom thought it looked bad and that I couldn't handle it. She then had my dad put a relaxer on my hair, which began 10 years of relaxer use. I'm now 35 and have been natural since I was 26. Interestingly, white Americans think my sister and I are twins, but Black Americans don't think we look much alike. When we tell white Americans we're just sisters, they ask if we have the same parents. Mind you, these are strangers. We do, but it's none of their damn business."

—Kindsey, 35, California

25. "I was raised in a rural village in the UK by my white mother. My father is Sri Lankan but was out of the picture before I was born. Due to the time my mother spent in Sri Lanka, she'd always talk about how she 'felt like [she] was Sri Lankan' and was 'shocked when [she] looked in the mirror and saw a white woman.' I felt like she was completely out of touch about what it's like to be a person of color in a predominantly white area — all while boasting about her stories in Sri Lanka for clout. It took me until my mid-20s to rediscover my history and learn about my beautiful heritage without any whitewashed input. However, I wish I could truly appreciate myself without the stains of my mother's 'bragging rights.'"

26. "The experience of being part of a mixed-race family is ever-evolving. I went from having people assume that I was being kidnapped as a kid to having people think that my (darker-skinned) father was my sugar daddy as a teenager. I went from having people assume that I was adopted while traveling with my (white) mother to having them think I was a trafficking victim while overseas with my (darker-skinned) uncle. While the assumptions and false accusations changed with age, one thing that remained constant was people trying to reconcile the fact that our family 'didn't match.' As a mother of a mixed-race child (who is Irish, Trinidadian, Black, and Puerto Rican), I've found that the base experiences are the same, but how we handle them are very different."

"This is one of the reasons I started my own small business catering to mixed-race individuals. We need a place where we can be 100% of ourselves and not be forced to choose a side."

—Brittany, 36, NYC

Did any of these resonate with you? Are you mixed race or from a mixed-race family? Let us know your thoughts and experiences in the comments below.

Note: Responses have been edited for length and/or clarity.