Three hundred and twenty light years away, there is a giant planet with three suns.

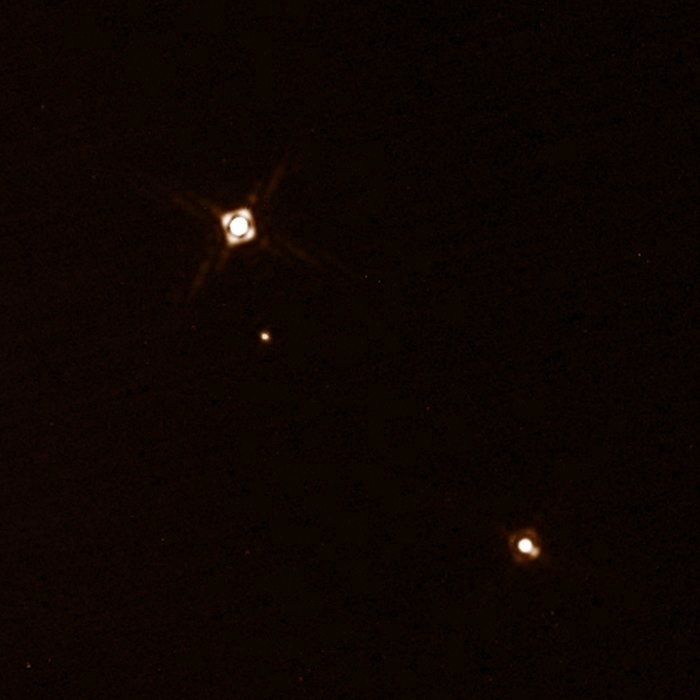

It's called HD 131399Ab, and it's been spotted by the European Southern Observatory (ESO)'s Very Large Telescope in Chile. The resulting study has been published in Science.

It's the first time an exoplanet – a planet outside our solar system – has been seen in a three-star system.

It's a massive world, about four times the size of Jupiter, the biggest planet in our system. It's also very young, by planets' standards – about 16 million years – and relatively cool, about 500°C on its surface.

It's also unusual because there's an actual photo. We know about the existence of about 3,400 exoplanets, but almost all of them have been detected by indirect means.

For instance, the Kepler space telescope, which has spotted more than 2,000 exoplanets, looks for stars that briefly dim and get brighter again as planets pass in front of them. It doesn't actually see the planets themselves.

There have only been a handful of exoplanets actually seen with a telescope. They're small and dim, so it's much harder to see them than it is to see stars.

"There are not very many directly imaged planets at all," says Dr Markus Kasper, an ESO engineer who worked on the study, "and all the rest of them are orbiting single stars."

Being able to see it means that researchers can tell more about the planet. They can see light coming through its atmosphere and use the information there to tell what gases are in it. "We've analysed the photos, and confirmed that there is methane in its atmosphere," says Kasper. Further observations will hopefully reveal even more.

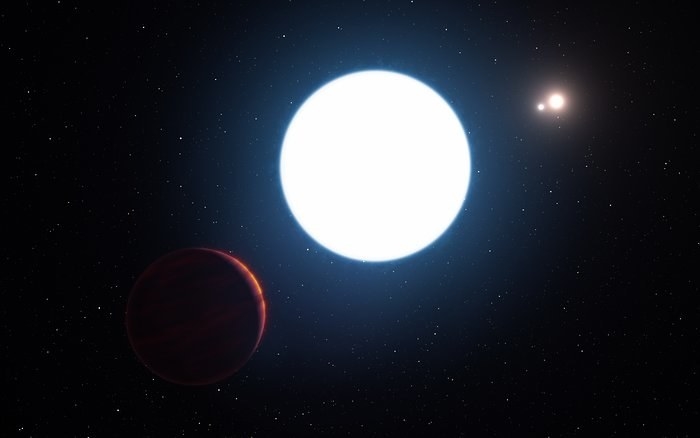

When people think of planets with more than one sun, the usual comparison is Tatooine, Luke Skywalker's home world in Star Wars.

But this isn't like that at all.

"Tatooine has two suns, and the planet goes around both of them," says Amaury Triaud, an exoplanet researcher at the University of Cambridge who was not involved with the study. "This one is a planet orbiting one star, with the other two stars orbiting each other far away."

Tatooine would be what is called a "circumbinary" system, while this is an S-type, or satellite-type, system.

That means that someone on the planet would see one bright sun and two dimmer ones.

"It depends where in its orbit the planet was," says Kasper. "If you're between the stars, there would be no day and no night. There'd either be one star in the sky or two.

"But if you're on the far side of the system, you'd have three suns the sky at once." The binary stars would be a lot dimmer, but still bright enough to cast shadows, he says.

It's also a really enormous system. The planet is about 80 times as far away from its sun as we are from ours, and its year is 500 Earth-years long.

"It's about three times as far out as the orbit of Pluto," says Kasper. "The other two stars are in a very close binary, about 10AU [astronomical units, the distance from the Earth to the sun] apart, about 320AU from the main star."

The orbit appears to be stable, as well. In multi-star systems, that's fairly unusual, because the other stars pull the planet's orbit around, and either throw it out into interstellar space or make it crash into the sun.

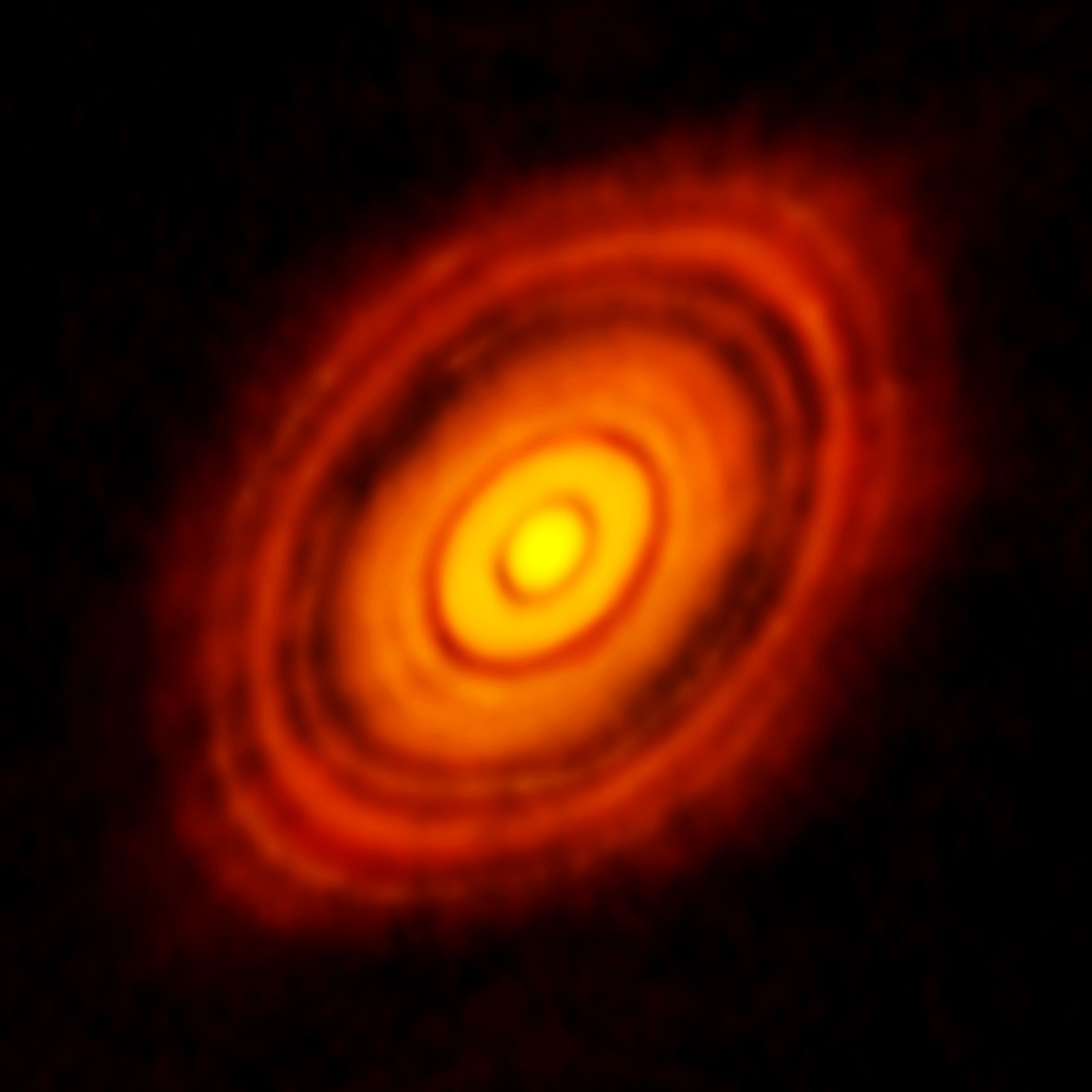

A planet that massive couldn't have formed that far from its star, so it must have come from somewhere else.

Planets form from the same disc of rubble and gas that stars themselves are made from. But in this star system the disc wouldn't extend out enough to make a planet the size of HD 131399Ab that far from the star.

"It can't have formed out there," says Kasper. "It’s a clear indication that it must have either been injected into the system from elsewhere, or moved outwards from a closer orbit, or possibly formed around the other two stars and moved across."

It's not possible to tell which it is yet, because the 500-year orbit means it takes a long time to see how it moves. "With more observations, we could tell, but it’ll take several years," says Kasper.