Leading British scientists have issued a stark warning to the government that further funding cuts will cost the UK its place as a world-leading centre for science, technology, and engineering.

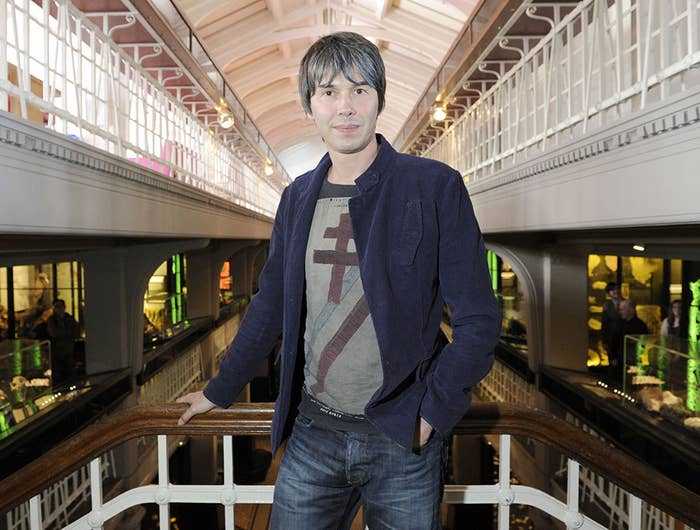

Amid rumours of swingeing cuts to research budgets in next month's spending review, Prof Brian Cox and other top scientists told BuzzFeed News that five years of real-terms decreases had already created a funding crisis.

Cox, professor of particle physics at Manchester University and presenter of BBC science programmes, said British science is "at the point where we can't withstand it much more", and that real damage is being done to "a capability which has been built up over centuries".

For the last five years, science funding in the UK has been subject to a "flat cash settlement", with no increases in funding – meaning that, due to inflation, funding has dropped in real terms by about 13%. The science community believes that anything other than a real funding increase in the spending review will deepen the crisis.

Dr Jenny Rohn, a microbiologist at University College London and the chair of the campaign group Science is Vital, said, "The rumours that we've been hearing are not good. We've been hearing that we'd be lucky to get flat cash again, and that we may very well get cuts – I've heard figures of 10%, 15%."

She and her colleagues warned that further cuts to the budget will leave Britain with impressive facilities but no researchers to use them.

"They like to invest in capital because they're usually shiny buildings and big telescopes," Rohn said. "But the core budget has not had a commensurate increase. So what this means is you have the shiny new telescope, but you have no scientists to run it, and you've got no electricity, you can't pay the maintenance bills."

British spending on research and development is already by far the lowest of any country in the G8 group of economically advanced nations, and dramatically below the average for the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

According to Science is Vital, the UK spends 0.44% of its GDP on scientific research. The average for the G8 is almost double that, at 0.79%, while the average for the OECD is 0.74%. Science is Vital says that no other G8 country has spent so little on research at any point in the last 20 years.

Prof Jim Al-Khalili, a physicist at Surrey University, described it as "an acute embarrassment" for British scientists in the international community, adding that the UK was bottom by a "significant" degree. "Everyone else spends a darn sight more on innovation, R&D, science, and technology than we do."

Cox said that the gap is going to widen: "Our competitors are increasing R&D spend. And it's not because they're groovy. It's not because they think that'll be nice. It's because they've accepted all the evidence which says that that's the path to sustainable economic growth.

The Department for Business, Industry and Skills (BIS), the government department which controls the bulk of scientific research spending in the UK, is expected to have to find cuts to its budget of between 25% and 40%. The business secretary, Sajid Javid, has reportedly said that he is keen that his department aims for the deeper end of that range. According to the Guardian, he has asked the management consulting firm McKinsey to model the effects of such cuts on the BIS budget.

The UK science budget is £5.8 billion. That represents almost one-third of the BIS's total budget, so making cuts of 25% without cutting science spending would require the BIS to find 37.5% cuts to the rest of its spending. Cutting 40% without touching science spending would involve a 60% cut to the rest of the department.

Cox and Al-Khalili told BuzzFeed News that cutting research spending was a "false economy". They point to a BIS report which found that every pound invested in research and development returns at least 20p per year – compared to an average return from investing in FTSE companies of 5.4% over the last 20 years.

"[It's the equivalent of saying that] I spend a lot of money commuting to work every day," said Al-Khalili. "What if I just go in three days a week? I'll save on those two days. It's a false economy."

Cox added that "every single piece of research that I have seen has pointed to the fact that every pound that's invested returns a significant dividend. Not even in the long term, but in the short-to-medium term."

Of the £5.8 billion, £4.7 billion is the "core budget", and £1.1 billion is "capital expenditure". The core budget goes to fund everyday running costs, such as equipment and staffing, while capital expenditure goes on building new projects. Since 2010 the core budget has been subject to the flat cash settlement, while the capital expenditure has been ring-fenced and has therefore gone up with inflation.

Cox pointed to the Isis particle accelerator in Oxfordshire, a flagship science project. In 2012-13 it was running at half capacity, firing up just 120 days out of a possible 240 due to budget shortfalls, although a spokesperson for Isis said funding has improved since then and last year it was up to 140 days on average for each of its two beams.

He said that the concern is that a prolonged shortfall in funding in any given area will lead to permanent damage to the UK's expertise in that area. "You can't turn the taps on and off. We've seen it in particle physics, where you lose the ability to design and build accelerators if you're not careful.

"It matters, because particle accelerators are increasingly central to medical treatments in many areas. You'll lose that ability in the economy, and it's extremely difficult to get it back."

Cox said that the recently announced plans to have a French company, EDF, backed with Chinese money, build a nuclear power station at Hinkley Point are a warning of what will happen.

"Twenty years ago, we were world leading in nuclear technology. And now we can't build them," he said. "Now we've decided we want to build them again we have to get French and Chinese companies to do it. You can't turn it back on again. We've lost the ability to do cutting-edge nuclear engineering, because we underinvested in not only nuclear reactors but in the skills base as well."

Despite the low levels of spending, British science is famous for punching above its weight: It has 1% of the world's population, but generates about 8% of the world's scientific papers, and about 16% of the most highly cited (and therefore influential) papers, according to the journal Nature.

But the scientists warn that this is at risk. "It's a danger, because the government can say: 'Look! Clearly you're doing very well. What do you want more for?'" Al-Khalili said. "[But] how we're doing now is linked to how we were being funded 10, 20, even 30 years ago. There are lots of projects and things that don't come to fruition or show the output until many years later. So if we're doing well now, that's because we were funded better decades ago. But what's happening now is that it's going to start to bite."

Rohn said: "If science continues not to invest, then … we will haemorrhage talented scientists in this country. They'll go to other countries that are more well-funded, and we won't be able to attract people from abroad… It's getting to the point where you talk to young scientists about whether they want to come and work in my lab, and they say 'Actually no, the prospects aren't very good in the UK, I'm going to go to Germany or Japan.' So we are literally seeing this happen now, that people are rejecting the UK as a place to do research."

A further concern for scientists is that the new minister for science, Jo Johnson, is an unknown quantity. "We've got a new science minister who's just learning the ropes," said Al-Khalili. "We don't yet know whether he's going to fight our corner in the way that David Willetts did very well. The view of the science community was that Willetts did a great job arguing our corner in the Treasury last time around, in the face of quite stringent cuts."

A spokesperson for BIS told BuzzFeed News: "Science is a priority area for growth and productivity and we have committed to a real-terms investment of £6.9 billion in science capital up to 2021." That £6.9 billion is equivalent to the existing £1.1 billion on capital funding spread over six years and adjusted for inflation. On changes to the core budget, the department said: "Decisions on funding beyond 2016 will be made during the spending review which will examine where best to make robust investments in science and research."

A spokesperson for the research councils, which channel most of the public investment in science to the researchers who carry it out, said they "will continue to make a strong case to government for sustained investment in the research budget", but that "in order to ensure that we make every pound we receive count for research we have committed to make savings of 20%-25% from our organisational operating costs over the next three years".

The results of the spending review will be announced on 25 November. Cox, Rohn, and Al-Khalili are all signatories of a letter sent by Science is Vital to the Telegraph in 2013, signed by 54 senior scientists including seven Nobel laureates, calling on the government to increase science funding to boost the country's economic growth.

CORRECTION

The scientists interviewed in this piece signed a Science is Vital letter to the Telegraph about science funding in 2013. An earlier version of this piece misstated the date of the letter.