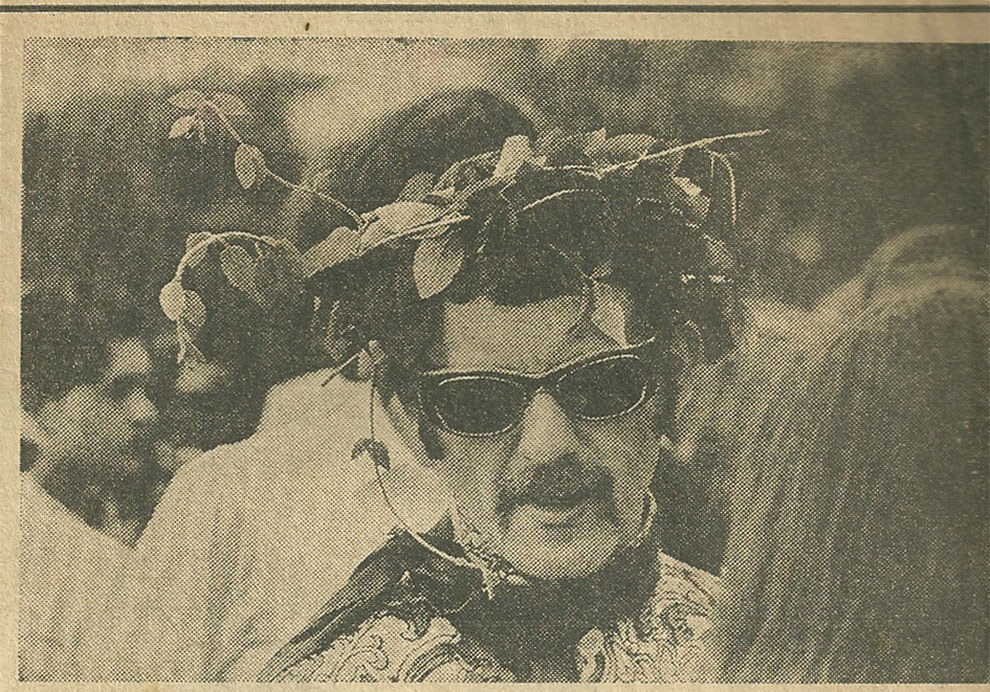

In 1964, Lee Harris was a driving force behind the prohibition of drugs in Britain. Now, more than 50 years later, he hopes to run for London mayor on a platform of legalising cannabis.

"I was a moralist," he says. He is 79 now, and grandfatherly, standing behind the counter of Alchemy, the head shop he runs on London's Portobello Road, a Buddhist pendant around his neck, spliff-rolling papers and bongs all around him. "I saw the mods taking their pep pills [amphetamines], 16- and 17-year-olds taking 80 pills over the weekend. So I got in touch with the MP for Paddington, Ben Parkin." Harris's intervention, at least according to one criminologist, began a sequence of events that led to the 1964 Drugs (Prevention of Misuse) Act. "I started off as a moral crusader."

Now, he wants to undo what he sees as the damage his intervention has caused. On 26 November, at Conway Hall in Holborn, he hopes to be nominated as CISTA's candidate for the London mayoral elections. CISTA is the "Cannabis Is Safer Than Alcohol" party. "I've got to win the hustings," Harris says, "but I think they want me."

"There's a worldwide movement towards decriminalising cannabis," he says. "It's coming, it's snowballing. The laws are archaic. Now cannabis is part of mainstream society."

Harris is a South African, although he's been in this country for more than half a century. He fled his home country because of apartheid, and still counts as his proudest moment meeting Nelson Mandela before he did so, in the late 1950s. Occasionally the old accent surfaces in his voice. He has been running Alchemy for 45 years. Before that, he says, he was "a failed actor, playwright, a bit of a wastrel – in midlife, I hadn't learnt how to earn a living".

His moment of conversion, from moralistic anti-drugs campaigner to a key figure in the 1960s hippie movement and advocate for legal marijuana, came almost immediately after his victory with the Misuse of Drugs Act. After the amphetamine craze hit the newspapers, and the act was brought in, "when I came in again to the West End all the clubs were empty," he says.

"One of my friends ran a club there, owned by Ronan O'Rahilly of Radio Caroline, and he was raided. All the kids dropped their pills and he was sentenced to 15 months for running a disorderly house." Harris went to visit him in prison. "I thought, god, what harm I've caused my friends."

He realised, he says, that he had become what he fled in South Africa. "I was doing the things I hated in South Africa, banning things."

The law he helped create blew up in his face even more directly. "I suffered myself. My first criminal conviction was cannabis in 1967, coming out of a club when I'd been doing lectures. I had a tiny piece of cannabis, a five-shilling deal, 25p, and a plainclothes policeman grabbed me and searched me. No uniform, just a card, grabbed me and threw me against a wall, and gave me a £30 fine."

He was arrested and charged twice more, both times without any actual cannabis on him: "I was busted for selling cigarette papers. I did one day in Wormwood Scrubs, but it was quashed on appeal." Another time he was arrested when someone else was found to be holding a few grams of cannabis in his shop. He was acquitted.

The drug laws, he thinks, are behind a lot of the racial tension in Britain today. "When I was busted, I saw so many black people being brought in for smoking. So many people being stopped and searched. In South Africa black people had a slogan: 'Police raids, police state.' And when I came to England I found police raiding people's homes, stopping them in the street.

"I knew there were riots coming, and a few months later Brixton was on fire, Bristol was on fire. And they started, usually, after a raid for cannabis on a premises. Heavy-handed policing in Brixton and Bristol caused so much damage to the West Indian community, who came in the 1950s and 1960s, and who brought such lovely music and who loved to smoke a bit of weed. This [Notting Hill] used to be the front line."

The prohibition of drugs, he thinks, is also the reason that most weed in the UK is skunk. "Prohibition forces people to choose something that will sell well," he says. "It also created the legal highs, the synthetic cannabinoids. But those legal highs are a great prototype for how to sell cannabis legally. All the packets had health warnings on them."

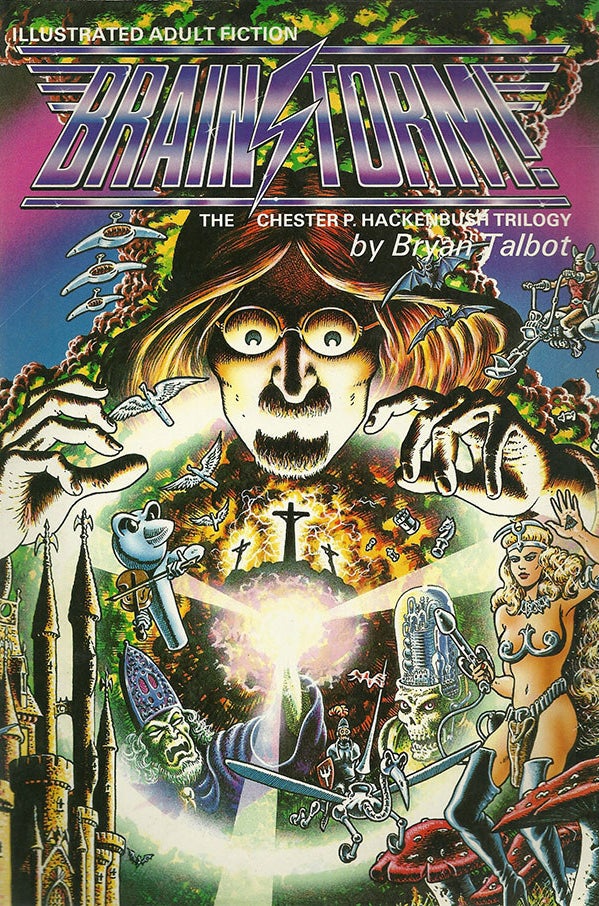

Brainstorm, the comic that Lee Harris published in the 1970s.

Everyone involved in 1960s counterculture seems to have come through Harris's shop at one point or another. He brought Allen Ginsberg, the great Beat poet, to England for one of his last performances; he knew Brian Jones, the ill-fated guitarist with the Rolling Stones. Bryan Talbot, now a great graphic novelist, made his name with the comic book Brainstorm, which Harris published. "I've been a radical activist for a very long time," he says.

But he has a surprising number of links to the Establishment, as well. He used to sell royal jelly to Fortnum & Mason's, and it turned out that Margaret Thatcher was one of his customers, along with Princess Diana.

And a few days before, he swears, Jeremy Hunt, the health secretary, was in his shop. "He was in here with his Chinese wife, when the doctors were marching. Unbelievable. And he said, 'Oh, I'll vote for you, if you stand for a cannabis party'." (A sceptical spokesperson for the Department of Health told BuzzFeed News, "Obviously, if he said that, it was a joke.")

The sheer number of people who he claims to have known is almost incredible, but as BuzzFeed's interview is going on someone walks in, a dark-haired man in his fifties who greets Harris warmly. "He gave me my first flat!" the man explains. It turns out to be Jaz Coleman, the lead singer of the 1980s punk band Killing Joke. "Jaz and [the famous violinist] Nigel Kennedy and me smoked strong stuff in Abbey Road studios," grins Harris. "Nobody said a word."

Coleman then launches into an anecdote about Kennedy smoking weed in the Buckingham Palace toilets, tripping on his way out and knocking Prince Andrew to the floor. (BuzzFeed News contacted Kennedy's management to confirm or deny this story, and was told "I'll ask him, but there's a good chance he won't remember.")

The fact that stories like that tend to provoke amusement, rather than horror, suggests that cannabis has lost its power to shock. "It's been through various phases since Reefer Madness," agrees Harris. "Now it's resurgent."

CISTA, the party he's hoping to run for, was founded by the man behind Bebo, Paul Birch. "I believe he sold it in 2005 to AOL for $850 million, so he's got a bit of money," says Harris.

Harris certainly believes in the party's central premise, that cannabis is safer than alcohol, and in fact is a strong believer in the medicinal uses of cannabis. (One man walks in to buy six packs of rolling papers, and the two have a discussion about the best type of weed to use if you have migraines. "Blue Cheese," Harris suggests, helpfully.)

He doesn't know what their other policies are, beyond ending the war on drugs, "but I presume we'll have to work them out, on housing and the other problems for London. Gentrification will be a very big thing."

He's been campaigning against the law for so long – "I helped get signatories for the first Times advert in July 1967, saying that the laws are immoral in principle and unworkable in practice" – that it must be hard to believe that things will ever change.

"It's hard to know," he says. The current government "has got itself in a pickle, because they've banned everything, with the ridiculous psychoactive substances bill. Laughing gas, everything. So how they can backtrack I don't know." But he thinks that the time has come. "I hope we can shake them up. And I think in London cannabis has really got a lot of backing."