A new "three-parent baby" technique could be licensed for use on patients as soon as the end of this year, a spokesman for the Human Fertility and Embryology Authority (HFEA) has said.

The new technique, "early pronuclear transfer" or ePNT, is reported in a study published in Nature on Wednesday. It could allow women who have potentially fatal mitochondrial diseases to have healthy children, instead of passing the diseases down.

Most of the cells of our bodies each contain thousands of mitochondria, which provide energy for those cells to operate. Billions of years ago, mitochondria were free-living organisms, bacteria, so they have their own DNA separate to our own.

Sometimes that DNA develops a mutation, and the mitochondria go wrong. It can have devastating consequences. Mitochondrial diseases can have symptoms including diabetes, blindness, deafness, learning difficulties, muscle wastage, and early death.

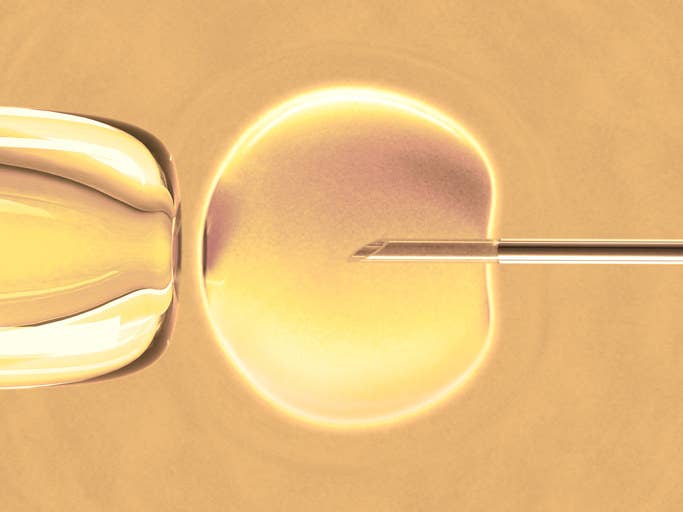

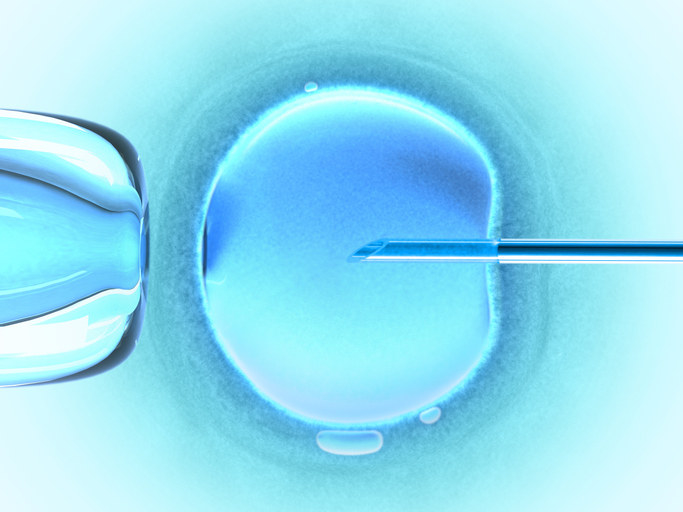

In ePNT, the nucleus – the part of the cell that contains our DNA – is taken from a fertilised egg taken from a woman with mitochondrial disease.

It is then transplanted into a fertilised egg taken from a healthy woman and grown into an embryo. Other techniques involve transplanting from an unfertilised egg.

The study found that ePNT produced high-quality viable embryos that were "indistinguishable" from those that lead to healthy babies in IVF clinics. Researchers say that it will lead to normal pregnancies and reduce the risk of babies being born with mitochondrial disease.

An HFEA spokesman told a press briefing that, now that the study has been published, a licence could be granted as soon as the end of this year.

Last year the British parliament voted to make mitochondrial donation techniques legal. Mitochondrial donation is better known as the "three-parent baby" or "three-person baby" technique, although scientists don't tend to use those terms, because the amount of DNA received from the "third parent" is minuscule – just 37 genes instead of the 20,000 in the nuclei of your cells.

Professor Doug Turnbull of Newcastle University, one of the authors of the study, told the briefing: "Mitochondrial disease affects a minimum of 10,000 patients in the UK.

"We are able to treat many symptoms, such as heart failure or epilepsy, but there’s no cure, and for many patients it’s a severe progressive disorder which in its most severe forms leads to death."

Professor Mary Herbert, another of the study's authors, told the briefing that the embryos created with ePNT were "indistinguishable from those created by normal IVF", and that there was no difference in the risk of chromosomal abnormalities.

"By any measure we’ve looked at, we’ve not found a harmful effect of the procedure," she said, "but there may be unknown ones that come to light. That's the same with any medical procedure."

The study used 500 eggs donated by 64 women. Researchers fertilised them using IVF techniques, let them grow for a day, then removed the nuclei from the "patient" embryos and implanted them into the "donor" ones. They found that only about 40% survived, so they tried implanting earlier in the process, to give the embryos time before they started dividing – hence "early" pronuclear transfer. "It involved working into the small hours," said Herbert, but the success rate went up to around 90%.

One risk with mitochondrial donation is that some unhealthy mitochondria can be transferred across with the nucleus into the healthy cell. This "carry-over" could lead to a child being born with the symptoms the technique is meant to avoid, or perhaps they might avoid the symptoms themselves but then pass them on to their children. However, ePNT has a carry-over rate of less than 2% on average, which is well below the safe limit. "If you keep it below 5% there’s a low probability of transmission to the next generation," said Herbert.

Researchers say that the ePNT technique has a bonus in that it works best when the patient's eggs are preserved using a technique called "vitrification". That's good news for would-be mothers who are worried that they are running out of time to get pregnant, because they can preserve their eggs now and use them when the technique is licensed and available.

Dr Rafael Yáñez-Muñoz of Royal Holloway, University of London, told BuzzFeed News: "This is certainly very exciting. These are some of the leading groups in the UK, and they've been working to bring forward the possibility of mitochondrial donation. I imagine they'll now go back and ask the HFEA for a licence.

"The UK is leading the world in this."

He warned, however, that there are ethical concerns over ePNT. "This work involves the destruction of the nuclear DNA from the donor's egg – meaning that the donor embryo is effectively destroyed. That's unacceptable to some people, and we have to take those concerns seriously. [Other techniques] involve unfertilised eggs, so you don't destroy an embryo."

Sarah Norcross, director of the charity Progress Educational Trust, which works on infertility and genetic disorders, told BuzzFeed News: "The HFEA now must reconvene its expert panel to consider these findings. For the sake of patients hoping to be treated with mitochondrial donation, we hope that this will be done without delay."

Liz Curtis, CEO of the Lily Foundation, a charity to support families with mitochondrial disease, which she founded after she lost her daughter Lily to the disease at eight months old, said: “It’s really amazing to think that soon parents could have the opportunity to extend their family using this technique, after this study found no safety issues, and researchers think there’s a good chance it can prevent mothers from passing on mitochondrial disease to their children.

“I lost my daughter Lily to mitochondrial disease nine years ago, and it’s too late for me to think about another baby, but for so many families this technique is their only chance of having a baby born free of mitochondrial disease.”