The average height of people in a country is a useful guide to how healthy and, especially, how well-nourished they are.

Height is partly genetic, but it's also heavily influenced by your diet in childhood and whether you've suffered from infections.

Now a huge new analysis by a global collaboration of scientists has shown which countries are the tallest, which are the shortest, and how it's changed over the past 100 years.

The study, published in the journal eLife, was coordinated by researchers at Imperial College London and looks at the measured height of men and women aged 18 since 1914. It's an enormous piece of research, collating data from 18.6 million people. Dr James Bentham, a public health statistician who worked on the project, says: "It is the most comprehensive height database ever assembled."

Here's what it shows. In 1914, Swedish men and women were the world's tallest.

Swedish men were, on average, 172cm tall – a little shy of 5 foot 8 – while the women were 160cm tall, or 5 foot 3. But men from the USA and Canada were pretty whopping as well, while most Europeans were fairly average in height.

People in Mexico, Central and South America, parts of the Middle East, and South East Asia were the shortest. Men from Laos were the shortest, at an average of just 153cm tall – 5 foot. Guatemalan women were 140cm or 4 foot 7.

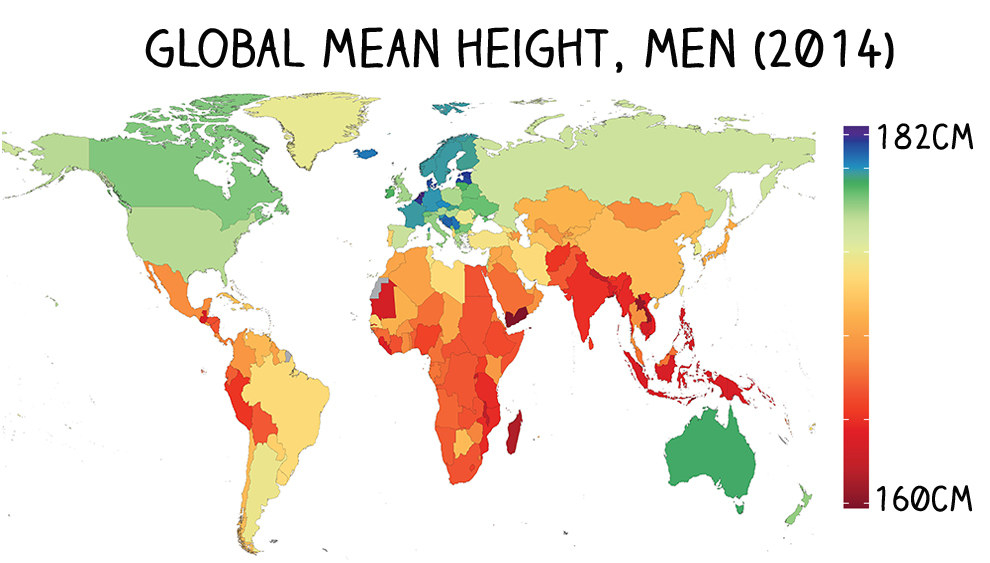

The whole world has got taller since then. But it's not been uniform. Dutch men and Latvian women are now the tallest.

The average Dutch man is now 182cm tall – a whisker shy of 6 foot. And Americans, who used to be right up among the tallest, have dropped back to mid-table.

"The good news is that being taller is associated with longer life expectancy, lower risk of premature death, and a lower risk of dying of cardiovascular disease," says Majid Ezzati, a professor of public health at Imperial and the leader of the research. There is also, he says, a lower risk of death in childbirth for taller people, but a moderate raised risk of some cancers.

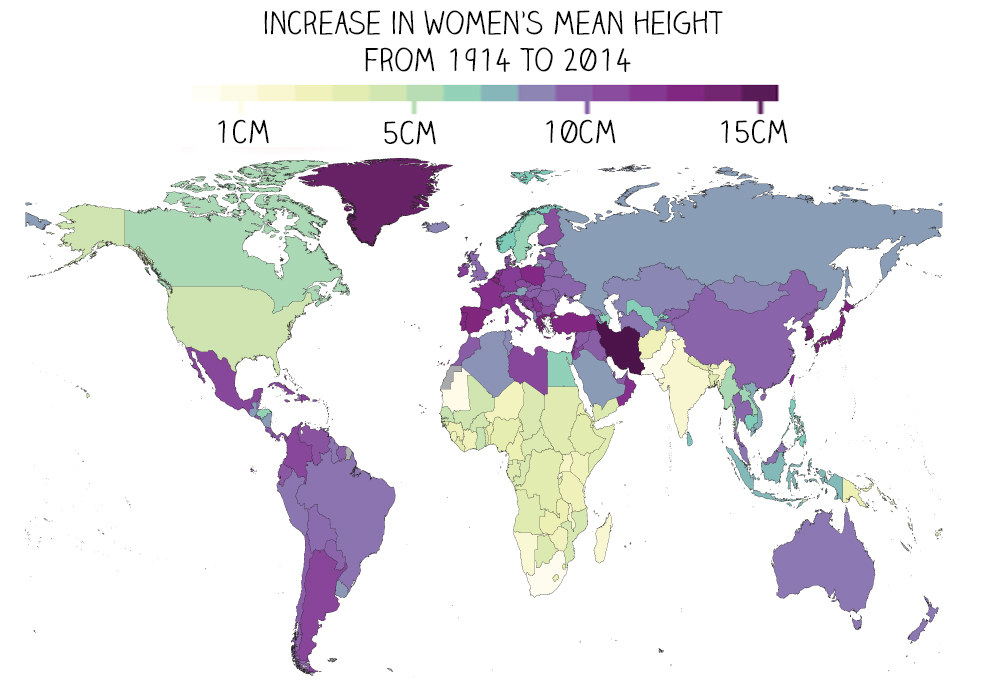

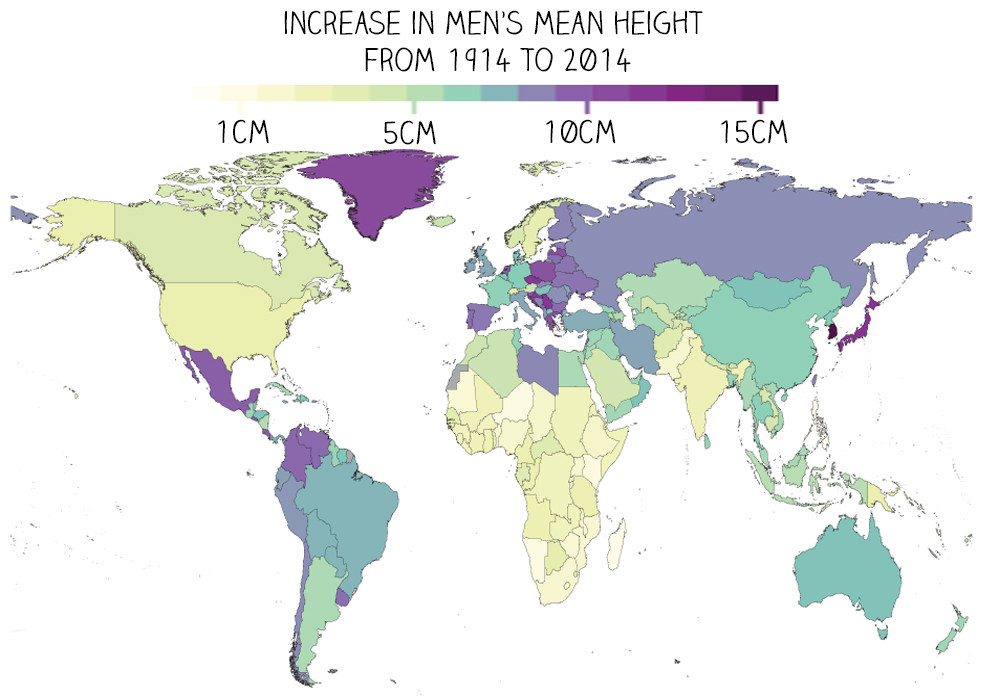

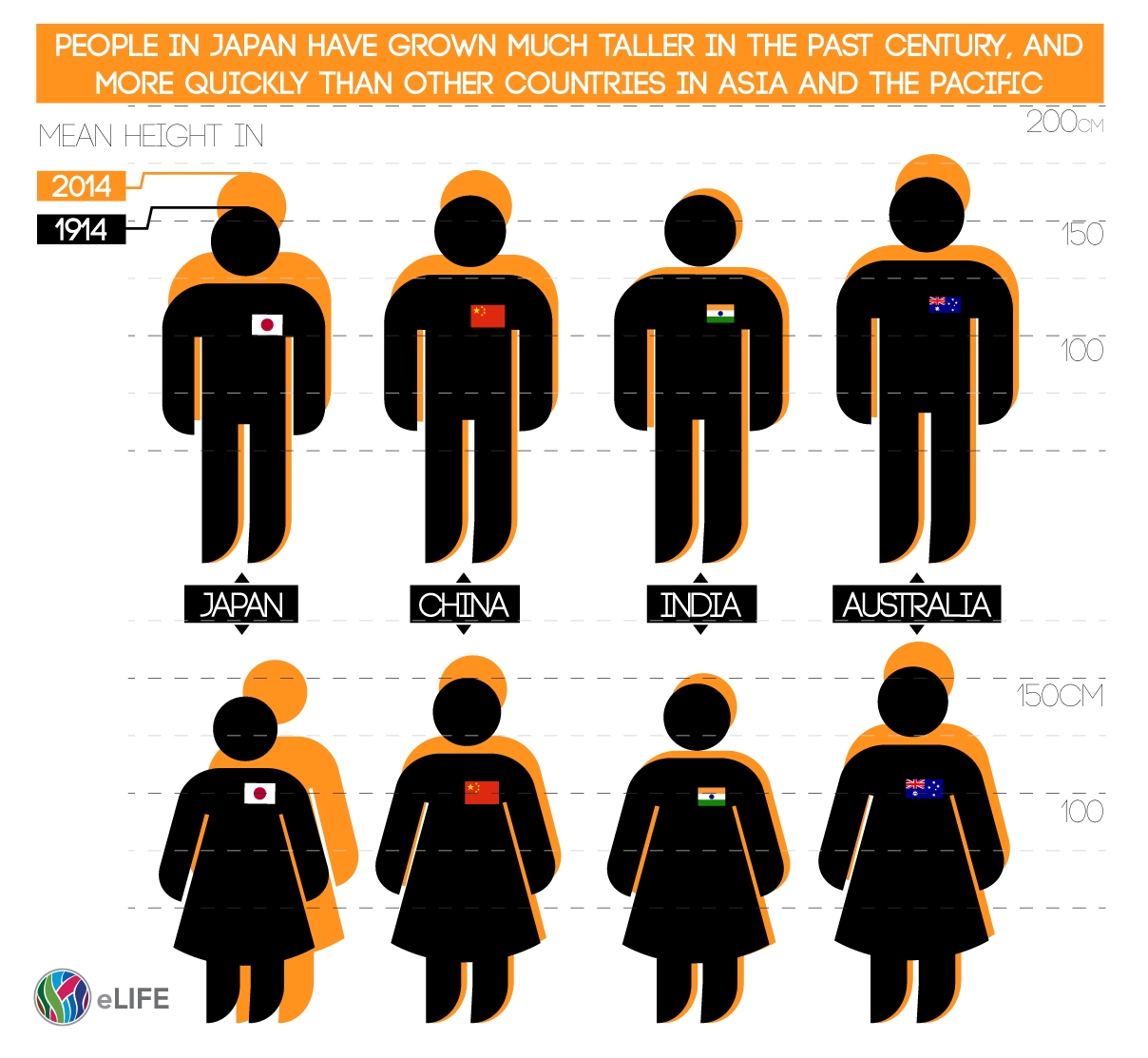

The study also looked at who's grown the most. Japanese and South Korean women have shot up, as have Iranian men. But African people, who used to be relatively tall, have stagnated.

The average Iranian 18-year-old man in 2014 was more than 15cm – about 6 inches – taller than his 1914 counterpart. People in South America and East Asia have shot up. Most European countries have grown significantly (British men are 10cm – 4 inches – taller now, for instance).

North Americans and Scandinavians have grown less, but that's not surprising since they were already among the very tallest.

But people in sub-Saharan Africa have barely grown at all. It's a similar story in South Asia – India, Bangladesh, Pakistan.

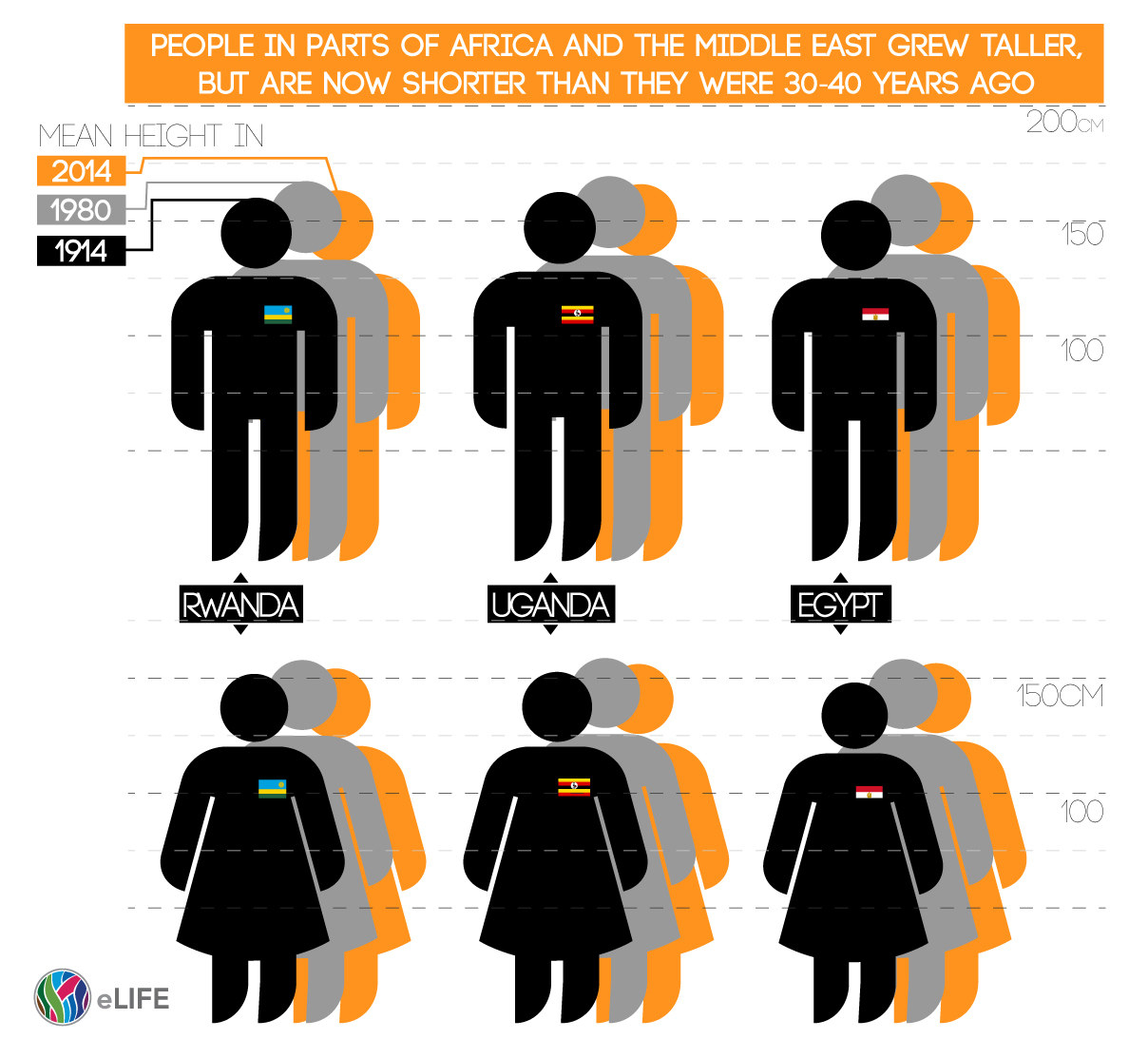

The African story is even more surprising – and alarming – when you look at the data from some years in between.

In 1980, men and women from several African countries were taller than they are now – so while the rest of the world has got taller, many Africans have been shrinking.

"The reversing trend in Africa clearly indicates a major problem from a nutritional point of view," says Ezzati. "We know that height was rising up until the mid-1990s.

"People have argued that it's due to trade and political decisions – countries cutting their social services and healthcare systems. It's their version of austerity. Poor Africans in rural areas were affected, losing out on nutrition, education, and sanitation."

By contrast, people in Japan have grown enormously, while Indian growth has been slow.

This is important because it tells us a lot about how healthy these countries are.

"Height is a very good mirror for the social environment," says Ezzati. It tells you a lot about how much food a child is getting, he says, but also how much it is able to make the most of that food. "Think of nutrition as a bucket," he says. "Food is what you put in, but the bucket has holes in it – infections – which stop you being able to retain it." Children who are malnourished, or who suffer from lots of infections, will not reach full height. Animal proteins – meat and dairy – are most associated with height, he says, perhaps because they regulate the production of growth hormones.

And the researchers say there are things that governments can do about it.

"Judging by how some countries pull ahead and others fall behind, we shouldn't underestimate the role of policy," says Ezzati. "There are clearly policy levers that have an effect on people’s health." He points out that there is "80-year-old evidence" that when milk is given as a supplement in schools, children grow taller.