Everyone says SF isn’t what it was. Everyone says the past five years have changed the city tremendously. Saito sees the city floating above the earth-- above the attacks in Paris, above the refugee crisis in Europe, yet also somehow acutely responsive (evasive?). Nonetheless, the city cannot escape its own internal crisis: housing crisis (identity crisis?). Middle income families can’t afford it. Long-term residents are leaving. The homeless are being pushed onto Market St., onto the doorstep of some of the world’s largest tech companies, who are content to surveil and monitor, but not intervene.

Someone on the street said SF is the technological petri dish of the world, that the concomitant economic changes will spread across the globe. More routine tasks, both physical and cognitive, will be automated, shifting power from labor to capital. Markets will continue to be digitized and networked, creating massive opportunities for economic super-stars, but fewer opportunities for everyone else. All of this economic change has the effect of centralizing wealth and power; it’s the best time to be a person with the right skills and the worst time to be a worker without technical expertise.

Our political institutions are incapable of keeping pace. Does that mean that the responsibility for those who aren’t able to meet their own needs falls on entrepreneurs? How often do they bemoan the inefficiency of government while simultaneously deferring to those institutions, ignoring the economic, social and political ramifications of their inventions? Do the entrepreneurs ever mention “a negative income tax, pigovian tax, value added taxes (VAT), universal basic income (UBI) or national mutual fund distributing the ownership of capital widely and perhaps inalienably, providing a dividend stream to all citizens and ensuring the capital returns do not become highly concentrated?” (quoted from The Second Machine Age)

Today’s networked city exacerbates inequality. Its geo-data and social-data facilitate both convenience and control. Technology companies model their customers and derive their location based on previous purchases, ushering them towards future purchases. Technology companies track customers through the street as relentlessly as they track them online. As companies continue promote a trade of one’s rights for one’s convenience, they produce more economic power and more political leverage, dangerously widening economic inequality and further reshaping the city to suit their preferences.

What kind of city is San Francisco creating with technology? Is it going to be a city in which the benefits of technological advancement reach everyone, or only a few people? Is it going to be a city where people have the freedom of privacy, or a city where they are intensively surveilled and controlled? Could San Francisco be the first city to implement some form of basic income (or related scheme)? Could it be the first city to explicitly adopt a Data Bill of Rights? It has the wealth and the expertise. We lead in technological innovation, why aren’t we also leading in social and political innovation simultaneously?

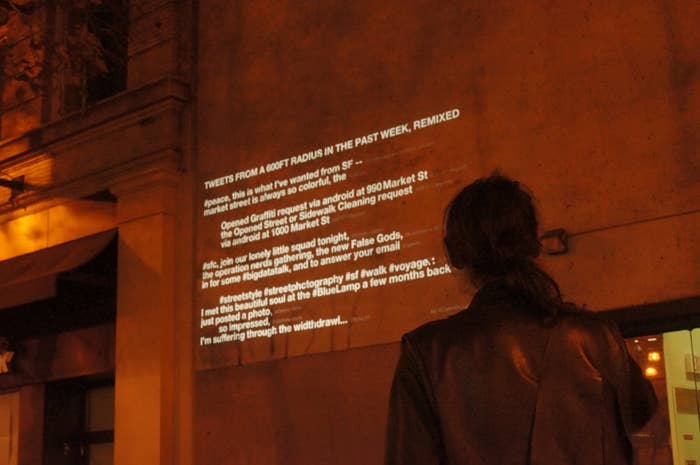

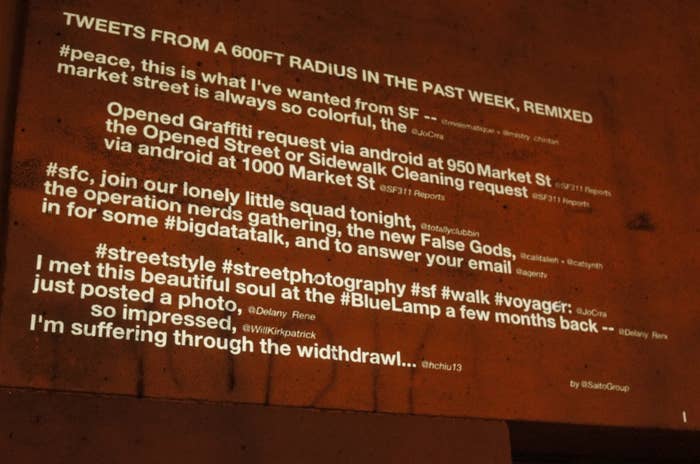

In all of this, Saito’s small part is probing the stream. Saito is gathering geo-located social media data from the area around Market St., but instead of using it to build models for marketing, Saito is remixing it into poems about economic damage and projecting those poems back onto the walls of the street. Saito is distributing a tool for citizen counter-surveillance, while simultaneously holding crypto-street parties where techniques for anti-surveillance are freely disseminated (inspired by Daniel Bustillio and Tim Schwartz). Saito doesn’t reject technology or technology corporations, but Saito is a social futurist, who believes the benefits of the network should be shared by all.