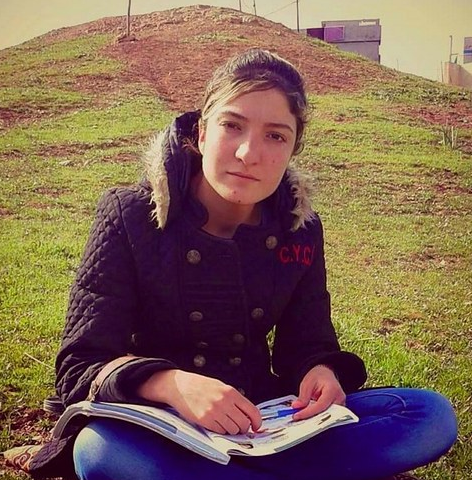

To an outsider, Nehad's Facebook profile looks like any other page owned by a 17-year-old. She shares photos of her life at home. News videos about her local community trickle into her feed. Friends comment on her life updates. She's a fan of the Twilight series, especially New Moon and Breaking Dawn, as well as the movie Titanic, and she likes to watch Arab Idol.

"Of course I'll add you on Facebook," Nehad said, speaking through an interpreter, as she took my phone from my hands and typed her name into the search bar. On her right hand she had a small tattoo of the letter "N", for her name. A second tattoo of her name sat along her left forearm, written in scrawled but delicate writing.

On a visit from her home in Iraq to London with the charity AMAR Foundation, Nehad spoke softly about her hobbies and lifestyle, and her face lit up at the mention of her family and friends. She was also remarkably open for a teenager who, up until this year, had been held captive by an ISIS militant who had tortured and raped her for more than a year.

Nehad and 27 members of her family were kidnapped two years ago from the northwestern Iraqi town of Sinjar. After being sold by one ISIS militant to another, she was taken to Syria and forced to live alongside her captor's wife and children in their family home. After months of torture and rape, she became pregnant.

Her story's not rare: the enslavement and rape of girls and women from the Yazidi religious minority has become a systematic part of ISIS's regime. Many are often sold or given as "gifts" to ISIS fighters or their supporters. Though Nehad and thousands of other Yazidi girls were able to escape, thousands more are still held captive by ISIS.

"It's difficult to see what ISIS do and hear what they're capable of, because I think the reality is so much worse than what the world thinks of them," Nehad said. "I find it hard to swallow, to cope with – they're allowed to get away with it, and grow, and do whatever they want."

But while Nehad has been marked by her horrific experiences, what's most striking about her is her determination not just to cope with her deeply traumatic recent past, but to recover the normal teenage life she had before ISIS threw it into turmoil.

Since her visit to London, Nehad and I have been sending each other GIFs and photos on Facebook Messenger: a set of smiling face emojis, a cartoon of a cat's paw, some animated flowers. Occasionally, we send a selfie to each other, too. For two people who don't speak each other's language, it's been an easy way to stay in touch.

"I take selfies and send them to my friends," she said. "They send me photos, too. I mostly use Facebook on my phone. I don't have much energy to do many things other that are fun."

While much of ISIS's influence in the global conversation stems from its activity on social media, for Nehad and teenagers like her, using social media is something that keeps her "normal", a space where she can voice her experiences and views away from immediate danger.

But she says that no matter what she and other Yazidi girls say, their voices are not being heard.

"Nothing I say or do is enough. We're talking about mass murder and ethnic cleansing on a huge scale – no message I or other girls have seems to be enough to cover that, or do something about it. Nothing we say makes it better."

But of course, for all her positivity and drive, the brutality Nehad suffered has left deep psychological scars that cannot just be ignored. Charities say the mental health of girls has been dangerously overlooked in the refugee crisis, particularly for those who have managed to escape torture and rape. In northern Iraq, medical centres are struggling to cope with a severe shortage of trained psychiatrists that has been brought on by the crisis, leaving those affected by ISIS atrocities without any formal support.

"Everything has affected me mentally, very deeply," Nehad says. "I'm constantly reliving it, because it hasn't finished. My faith is helping me cope, but I'm still waiting for the rest of my siblings to be returned, and until they're home it continues to affect me. The pain has ripped my life and taken it over."

Girls and women in Iraq suffering from complex conflict-related trauma is commonplace, and rates of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder are "dangerously high", according to the AMAR Foundation, which says that reaching safety has not brought an end to survivors' suffering.

Dr Ali Muthanna, the AMAR regional director for Iraq, meets many girls who have escaped ISIS and are "struggling to cope with the enormity" of what they've suffered. He says there is an urgent need to provide girls like Nehad with access to mental health care.

"All too often we see cases of girls suffering from severe depression, crippling anxiety, panic attacks, headaches, and nausea," he said. "Some self-harm, and many struggle to maintain relationships."

The charity says that some escapee girls, haunted by their memories and unable to voice and bear their pain, kill themselves.

"I like it like this, with a little bit of blonde in," Nehad said, playing with the streaks in her dark hair. She wishes she could still have her hair and makeup done in the local salon at the end of her road. She shared photos of her relatives, and said she longed to be back living in her town, where life was "simple" and family-orientated.

Memories of her old, peaceful life remain at the forefront of her mind – but she also thinks often about the baby she was forced to leave behind when she escaped. Trapped in her captor's home, and living alongside his wife and children, she was raped and became pregnant. After several attempts to terminate her pregnancy, she gave birth at the age of 16.

"When I first knew that I was pregnant, I had no feelings," she said. "I was afraid of it, it was a son of a criminal. But my mind changed as soon as I held him, I realised he was a part of me, I felt motherhood."

For many girls and women like Nehad who have been kidnapped, raped, or forced to leave a child behind, resituating themselves in a family setup that has been uprooted and rattled with such trauma can be a difficult task. Stigma is commonly attached to rape, and survivors can often be ostracised from their community and family – a problem that is particularly true for girls and women in ISIS-controlled territories where rape has been weaponised as a way to undermine someone's "honour".

Though Nehad has found it challenging to adjust to her new home, she said she and other girls she knows who have survived ISIS were welcomed home with open arms. Some charities in Iraq and Syria say that this acceptance is not all that unusual: While the stigma surrounding rape survivors is still prevalent, the number of girls and women in ISIS-controlled areas who have suffered sexual violence has become so great that it's created a shift in view among some communities who now choose to support, not reject, survivors of rape.

"Something different is starting to happen in some of the ISIS-controlled zones of Iraq and Syria," Yifat Susskind, executive director of women's rights charity Madre, wrote last February. "There, the sheer number of women who have suffered sexual violence seems to be creating a potential tipping point. We saw this change in Rwanda too, where rape was a systematic weapon of genocide. Afterwards, the critical mass of survivors triggered a new national conversation on sexual violence, on the morality of ostracising survivors and on women's human rights more broadly."

Despite the support from Nehad's family and community, at home underlying tensions remain. She says opening up about her experience has proved mentally demanding, and worries that confiding in her loved ones about her torment may make her parents' pain worse, especially as several of her siblings are still missing. She has ended up becoming the central source of strength within her own family.

"I can't tell anyone how think and how I feel. I can't even express much to my parents or family, so they don't get upset. I bottle it up inside of me," she said.

"My father doesn't allow me to be alone, so I don't get down. He makes sure that I'm always doing something, he takes me to the market or to my brother's house. My parents are feeling down too, and I'm the one in the family who gives them encouragement. I try so hard to keep my parents' spirits up."

Nehad attempts to inject doses of normality into her day-to-day life – talking about her views to her friends on social media, spending time with her parents, dyeing her hair like she did before ISIS stormed her town – that allow her to picture and plan for a future.

"For me, I want to complete my education, to study, and to become a teacher, and to get married and have a family myself. I also hope that I will see a day where my family are reunited, and brothers and sisters come back."

If you would like to help AMAR’s Escaping Darkness campaign you can find out more here (www.amarfoundation.org)

Nehad's rescue was partly co-ordinated by The Liberation of Christian and Yazidi Children of Iraq.