In 2014, I had been living in Texas for four years and really needed a Texas driver’s license. After one warning from a traffic cop, one incident that resulted in four tickets, and one infuriating trip to the DPS (what they call the DMV in Texas) where I left empty-handed, my husband told me in no uncertain terms that he was sick of being my personal Uber and that I needed to get my shit together.

So I went back, and after filling out the requisite paperwork and waiting the requisite hour, I was instructed by a DPS worker to just please step over there, ma'am, look into the machine, and read the letters.

Ha! What a silly formality for someone like me, an avid reader with perfect vision! I thought. I knew I had 20/20 vision, ever since getting Lasik when I was 18. I had the receipts. I stepped up to the machine, peered inside, and said what I now realize is an absolutely ridiculous thing to say if you’re taking a vision test: "Wait, you want me to read all these letters? But...I can't...see them?"

Like, what kind of sham test was this? Why would you show me letters written in a font that’s so small I can’t read them?

“Just try,” he said. Just try. As if I were a child convinced she didn’t need to go potty.

OK, fine, I thought. I’ll TRY to read your stupid illegible letters.

“Ummm, O...F?...ummm….C?…D...A…”

At that point, he cut me off and told me I could stop, as there was no point in continuing. And that is the very embarrassing way that I learned I need glasses. Again.

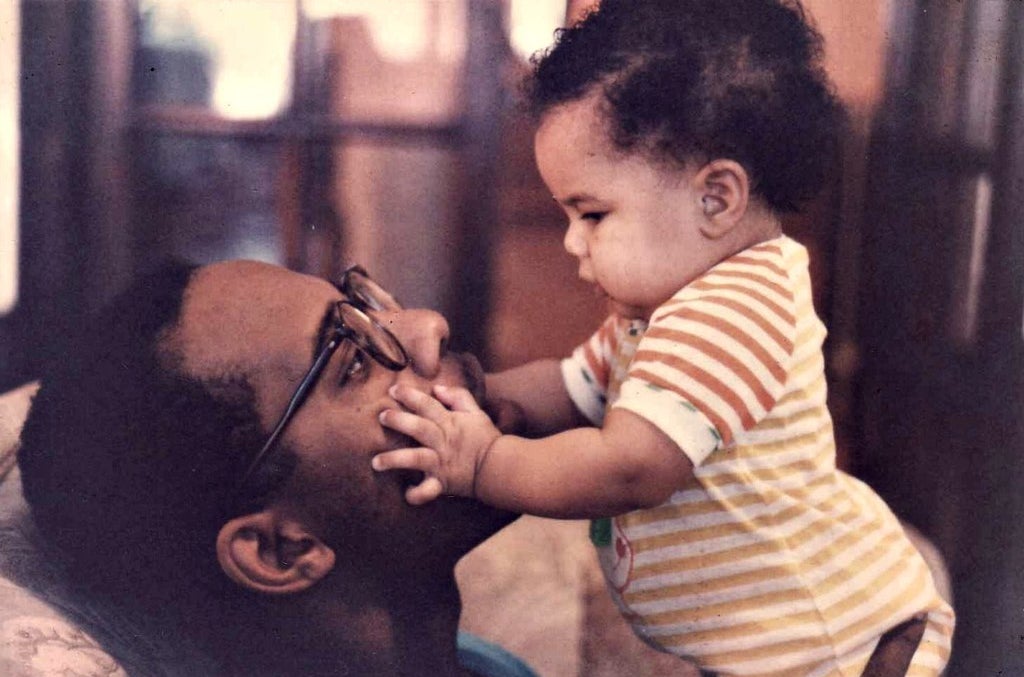

When I was 4 years old, my mom noticed that I was squinting at the black and green computer screen as I played the 8-bit version of Reader Rabbit. She took me to the eye doctor, where I got my first pair of glasses. Given how bad my father’s eyesight was, this came as a surprise to no one. He was one of those people whose glasses were just a part of his face, his weak vision a part of his identity. No one has ever looked at me and said, “You have your father’s eyes,” but I learned pretty early on that I actually do.

My glasses quickly became a part of my identity. I could never understand how other kids could lose or break their glasses. How could they be anywhere but your face? The only time they weren’t on mine was when I was sleeping — and in that case, they were on my nightstand, within arm's reach. I even wore them in the shower. When I was in second grade, I woke up in the middle of the night, feeling sick. I ran to the bathroom, paused halfway there when I realized I had forgotten my glasses, went back to grab them, and threw up in the hallway because I couldn't get to the toilet in time.

Every year on school picture day, someone would ask me if I planned to take my glasses off for the photo, a question that always baffled me. Why would I want a photo of myself that didn’t actually look like me?

I could never understand how other kids could lose or break their glasses. How could they be anywhere but your face?

In the summers, I developed a pale raccoon mask underneath my glasses while the rest of my face got tan — though few people saw it, because I so rarely took them off. My mom would sometimes snatch them off my face without warning. She could see all the smudges that I simply looked through, and it drove her crazy. "Ugh, you're just like your father, with your dirty glasses," she'd say.

The same year that I got my glasses, my mom and I moved from Chicago, where I was born, to a small town in Michigan, to live with my grandma. Much of that time is blurry to me, but I remember learning at some point during those years, from the family therapist my mom took me to, that my mom had left my dad because he had been using drugs.

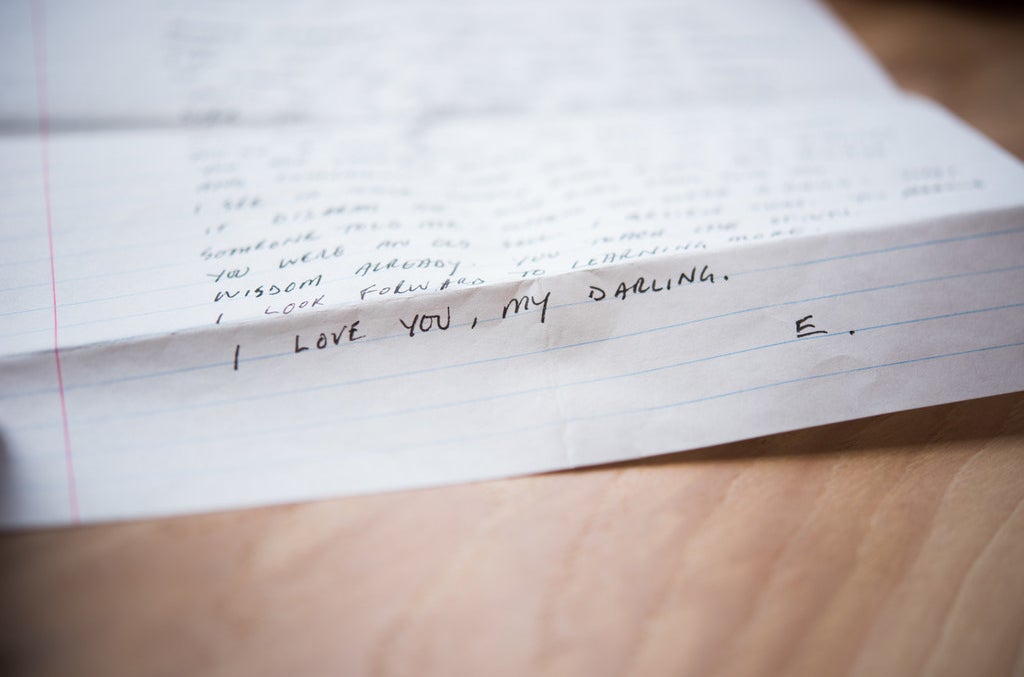

Learning that didn't change the way I felt about my dad; I loved him, just like I loved my mom. Over the next few years, I wrote him letters, and sometimes he wrote back, or sent me a card out of the blue. In one of his letters, he apologized and wrote that “mommy was angry with me for spending our money on stupid stuff.”

My mom took me back to Chicago a couple times to see him, and he agreed to come to Michigan for my seventh birthday in August. This was a big deal, as he’d never come to our house in Michigan before, and I was very excited.

The day we were supposed to pick him up at the train station, I was wearing coral-colored shorts and a white sleeveless button-front shirt. My grandma French-braided my hair. “You’ve gotten so big since the last time you saw your dad!” she said to me.

“Yeah, maybe he won’t even RECOGNIZE me!” I said.

“Oh, I think he’ll recognize you,” she responded. She put a yellow bow at the end of my braid.

When the train arrived, we waited for him to step off. We waited, and waited, and waited. Finally, my mom asked someone if she and my grandma could walk through the train to look for him. They did; he wasn’t there. When we got home, I called the number I had for him at the time, but he didn’t answer.

In October, he finally called. He told me he had missed his train on my birthday and felt so bad that he couldn’t bear to talk to me, which was why three months had gone by. I don’t remember what I said to him. I probably said, “It’s OK.”

I remember my mom taking the cordless phone out on the back porch to talk to him, and I remember catching the phrase “THREE MONTHS.” I also know that she told me it wasn’t OK, and that she was very angry. I remember being in my bed and her holding me in her arms as I sobbed about him.

The same year I turned 7, I really, really wanted The Jolly Postman from my class book order, and after bugging my mom about it, she — the woman who never received a dime of child support, who was, at this point, working minimum-wage jobs to support us, and who had every right to be angry about the fact that she couldn’t buy me this book — said, “Why don’t you ask your father for the money?” For whatever reason, I still blindly trusted him, so I did: I called him and asked him to buy the book for me.

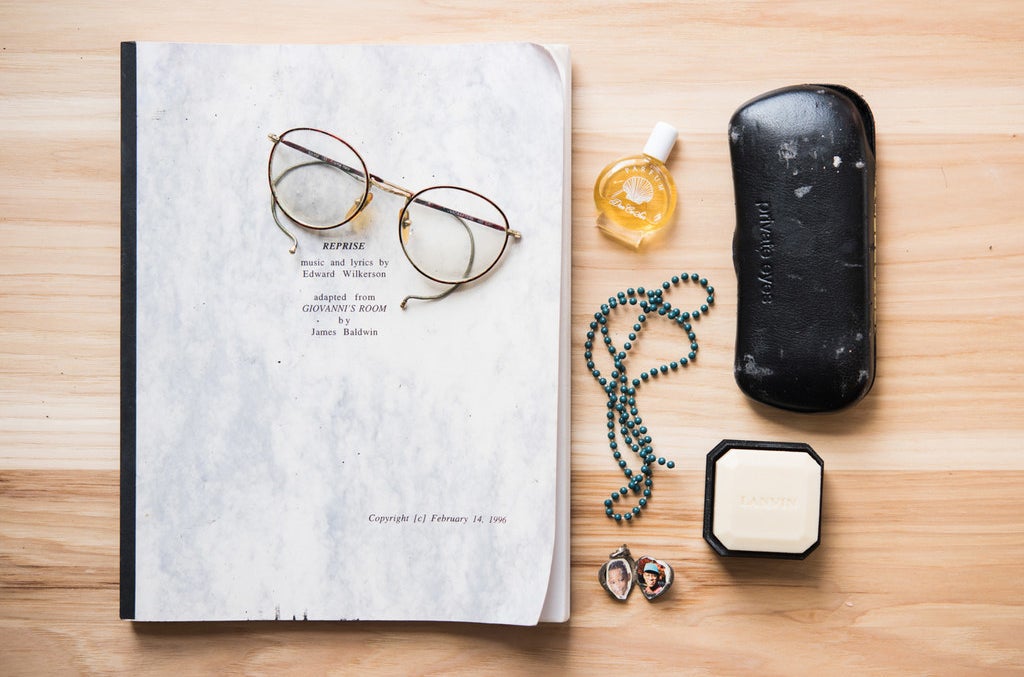

The Jolly Postman is one of the items I’ve always had in the mental log I keep of all the gifts he’s ever given me. The same year, he went to Mardi Gras in New Orleans and sent me a big package of gifts including a tiny bottle of perfume, some unused soap from the hotel bathroom, Mardi Gras beads, and a pretty stuffed doll that I named Sweetie Pie and slept with every night.

My dad wasn’t the parent that my mom and I wanted him to be, but I know he wasn’t a terrible person. He was, in fact, an incredibly charming and handsome and smart and talented person. He went to college on a full theater scholarship. He was an Equity and SAG actor, was a member of the Child’s Play touring company for several seasons, performed at Steppenwolf and the Goodman. He wrote scripts, composed music and lyrics, and sang. When we were all still living in Chicago, he bought me a little acting kit and would put funny makeup and silly wigs on me, and we’d perform plays in our living room.

He had the best laugh. I now get Facebook messages from his old friends who have been inspired to look me up in the decades since they last spoke to him; they always tell me how much he loved me, and how proud of me he was.

I was proud of him, too. I moved on from the birthday incident. I drew pictures of him and told my classmates that he lived in Chicago and that he’d been in commercials. When people complimented my performances in school plays, I told them that my dad was an actor.

In third grade, when I was in my ~Victorian phase~, I put a photo of him in a silver locket that I wore around my neck each day. I saw myself and my family situation as perfectly normal and didn’t fully understand that the other kids at my Catholic school in Michigan might not.

To their credit, those classmates were always very kind; they asked questions only out of curiosity, and no one ever made fun of me. The kids — who were all white, except for me — sometimes asked me if I was adopted, because they had only ever seen me with my white mother. They asked who the guy in my locket was, and asked if my parents were divorced. They asked if they could touch my hair.

I was open and honest about so many things, but there were still a few things I kept to myself because I knew on some level that they were secrets. I didn’t tell anyone about the drug use. And I didn’t tell anyone that when I was around 3 or 4, I’d overheard a conversation between my mom and dad where he said something to the effect of “My parents could never deal with the fact that I’m gay.” (I am not the first child to learn this by accident.) I don’t know how I even knew what gay meant, but I did — and just as I somehow instinctively knew it wasn't bad, for whatever reason, I also knew that I shouldn’t tell people that fact.

I was 11 when my dad came out to me. And when he told me via phone, not long after that, that he was dying of AIDS. He didn’t use that word, dying, but I knew what his diagnosis meant. I told no one about the conversation. In fact, the same night, I went to my sixth-grade dance as though nothing was wrong.

But over the next 18 months, I started to realize something was wrong. I was older, I was beginning to truly understand the ways he’d let me down over the years, and I was angry about it. I didn’t know how to tell him that, exactly — like 7-year-old me, 12-year-old me still said, “It’s fine” — but I started to pull away when he’d call me. Yes, he was sick, but I was also sick of his shit. Envisioning a world without him wasn’t that terrifying, because I’d already lived most of my life without him.

My dad died on my first day of eighth grade. I was sad, but he’d been so absent in my life that I was also, to some degree, fine. I stopped thinking about him as much, stopped talking about him with pride like I had when I was younger. I didn’t want to celebrate him, I didn’t want to mourn him. I just didn’t want to deal with him.

I didn’t want to celebrate him, I didn’t want to mourn him. I just didn’t want to deal with him.

I didn’t want to be defined by tragedy, to be seen as an open wound instead of a person. I hated (and still hate) having to deal with the inevitable onslaught of questions that people always had when I told them anything about my dad’s life or his death. Having an absent parent or a dead parent is bad enough, but dealing with other people’s reactions to this information can be even more exhausting, particularly when you don't feel the way they expect you to feel about it. And I found that it wasn’t that hard, as time passed, to essentially erase him from my story.

Every year when I went in for my eye exam, my ophthalmologist would tell me that when I turned 18, I could get Lasik surgery. It would bring an end to all this — to handing my glasses to my mom to secure when I went on roller coasters, to squinting during softball games because I couldn’t wear sunglasses, to being completely reliant on those two lenses from the moment I woke up until the moment I went to bed.

Six months after my 18th birthday, I had the surgery done. It was a little scary — when someone is taking a laser to your eyes, it's hard not to freak out — but it was over quickly. After just five minutes in the chair, my vision was well on its way to being 20/20. The next day, at my follow-up exam, it was there. My glasses were obsolete.

I loved the convenience of having perfect vision, but there were times when I felt a little naked without my glasses. I also felt like I’d been kicked out of a club. When friends commiserated about their eyewear, I had to explain that I could understand where they were coming from, perhaps even more than they could.

And when black, chunky glasses (exactly like the last pair I’d owned before Lasik) came into style, I felt kind of cheated. I dealt with the downsides of needing glasses for 14 years, and now it was cool to have them? I was being left out of a trend that was basically my birthright? I eventually got a couple pairs of fake ones, but, afraid of being exposed as a hipster fraud, I never really wore them.

When I had Lasik, I was told that I’d probably just need reading glasses in my forties. And like many underpaid millennials, I’d moved around a lot and gotten new and confusing health insurance each year, so I no longer had an eye doctor calling me to remind me to come in for a checkup. My attitude was, I got my yearly Pap smear; what more do you people want from me?

It never crossed my mind that I might actually need glasses (again) until I found myself at the DPS, 11 years later, taking an eye test that was supposed to be a formality — and failing miserably.

As embarrassing as that moment was, it was nothing compared to how embarrassed I felt when I actually put on my new glasses after an emergency trip to LensCrafters the next day. Because when I put them on, I could see EVERYTHING. Which was really amazing, but also low-key horrifying. I was relieved that my expired license meant I didn’t do much driving because — holy shit, there was a good reason they wouldn’t give me a new driver’s license. Also, what the fuck else could I not actually see?

After I got over my initial embarrassment, I welcomed my glasses back like an old friend. But my prescription is much lighter now, making me a slightly more casual glasses-wearer than I was before. I can, if necessary, run to the bathroom to throw up without them. And a whole new world of buying eyewear online is now available to me. A world that, frankly, I find overwhelming AF; I had to ask my friends who had been wearing glasses for, like, a mere five years how to buy mine online, which semi-enraged me.

We can try to write our parents out of our narratives, but parts of them will always be in our blood.

The eye doctors I’ve visited in the two years since that failed vision test have reassured me that my Lasik was done perfectly. It wasn’t the doctor’s fault; it was simply my DNA emerging to tell me that this modern newfangled surgery was cute and all, but it was time to stop playing and go be who I really am: my father’s daughter.

In the same way that my natural hair — the same texture as his — grows back in eight weeks after I have it relaxed, my bad eyesight eventually came through. We can try to use modern technology to tell our bodies what to do, but sometimes our bodies don’t give a fuck what we want. We can try to write our parents out of our narratives, but parts of them will always be in our blood.

After he died, my dad’s glasses sat alongside his urn at his memorial service. He left very few possessions for me to inherit, but I did receive a briefcase that held both a musical adaptation of James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room that he wrote — the magnum opus he was never able to get the rights to produce while he was alive — and his last pair of glasses. I keep both in a locked box with the perfume, the soap, the locket, what remains of the Mardi Gras beads, and every card and letter he ever sent me. (Sadly, Sweetie Pie was destroyed when my grandma’s basement flooded in 2007. But The Jolly Postman, which was on a bookshelf, survived.)

The glasses and the script are tangible reminders of the intangible things I’ve gotten from my father. I am a writer, I am incredibly nearsighted, I am his only child. I didn’t always get a birthday card from him, but I’ll probably get a new pair of glasses every year for the rest of my life.

Some days, I wear my contacts. Most days, I wear my glasses. My guess is that before long, the friends who met me in my 20/20 twenties will come to see my glasses as part of my face, part of my identity, and that feels appropriate. Because I think if my dad had imagined — when I was a little girl, or when he was dying — what I'd look like as an adult, he would have pictured me wearing glasses.