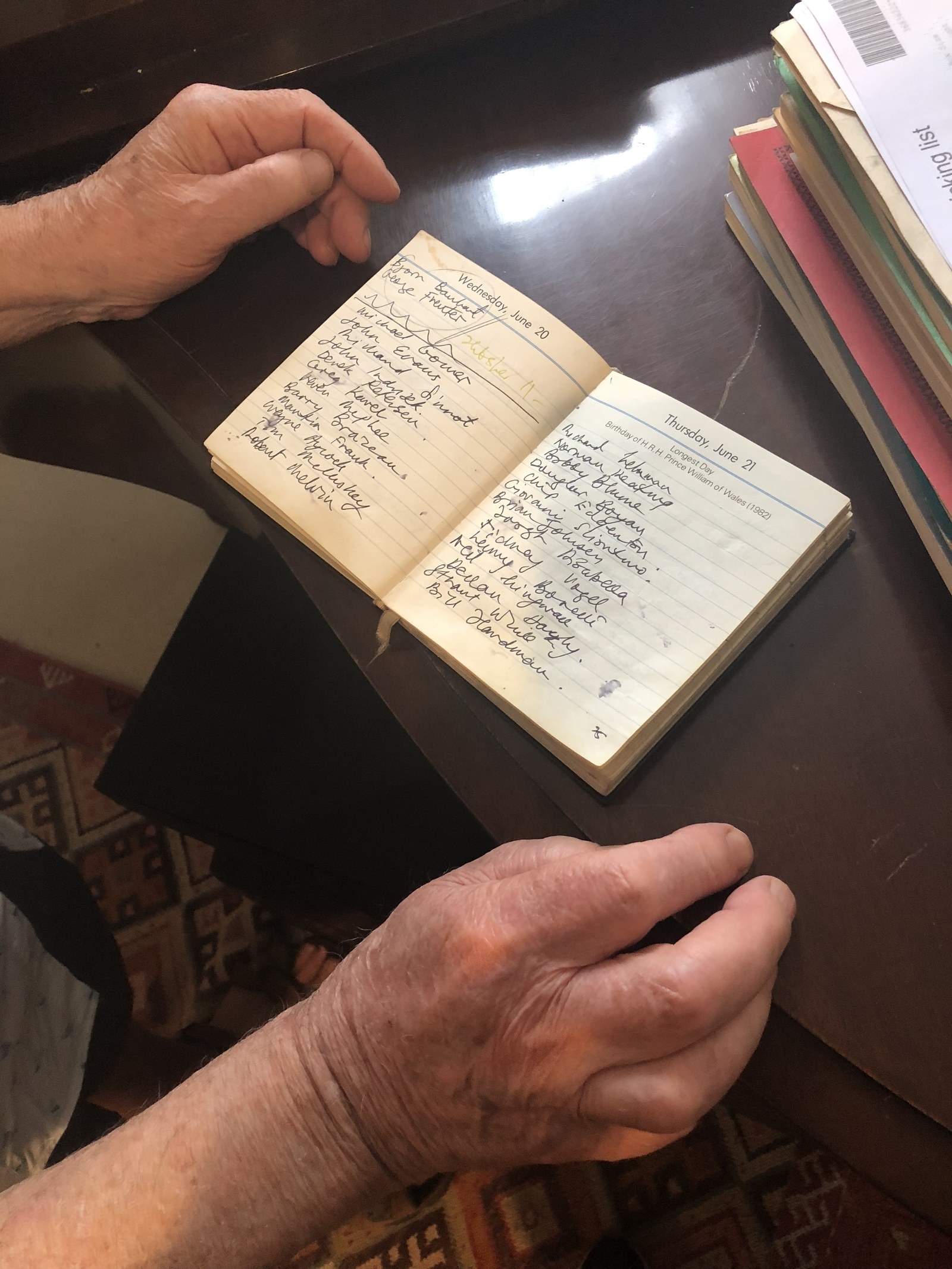

Dr Joseph Sonnabend reaches up to a bookshelf and pulls out a diary. The year is on the spine: 1984. He places it on top of his piano and flicks through until he finds the beginning of a list of handwritten names. He begins to read.

Michael Gomez. “He was an Hispanic guy.”

Richard Sinnot. “He died in St Vincent’s Hospital.”

Brian Johnson. “I still have a sweater he knitted for me.”

Greg Kavel. Kevin McPhee. Barry Brazeau. Sidney Vogel.

It is the list he kept of his patients who died of AIDS. Gomez was the first. Sonnabend stopped noting down the names when they reached the 300s. It did not take long.

He started writing the list in 1984, six years after he first suspected there was something wrong, that patients were suffering symptoms with no explicable cause. He tried to raise the alarm in 1979, two years before anything was reported in the press. He was ignored.

With his own sexual health clinic in New York City in the late 1970s and with a background in infectious disease, Sonnabend was one of the very first physicians to spot the early warning signs of what would become the AIDS pandemic. He had no idea what was about to hit.

He also did not know how influential nor how controversial he would become; that he would set up two major organisations that are now titans in the fight against HIV/AIDS; that he would set legal precedent in a landmark case of HIV discrimination, all while becoming the target of hostility from both activists and fellow scientists. It was a war, he says now, on all fronts.

Sonnabend’s life and career spans the entire 40-year known history of HIV/AIDS. What was unknown during that time was how his other talent carried him through.

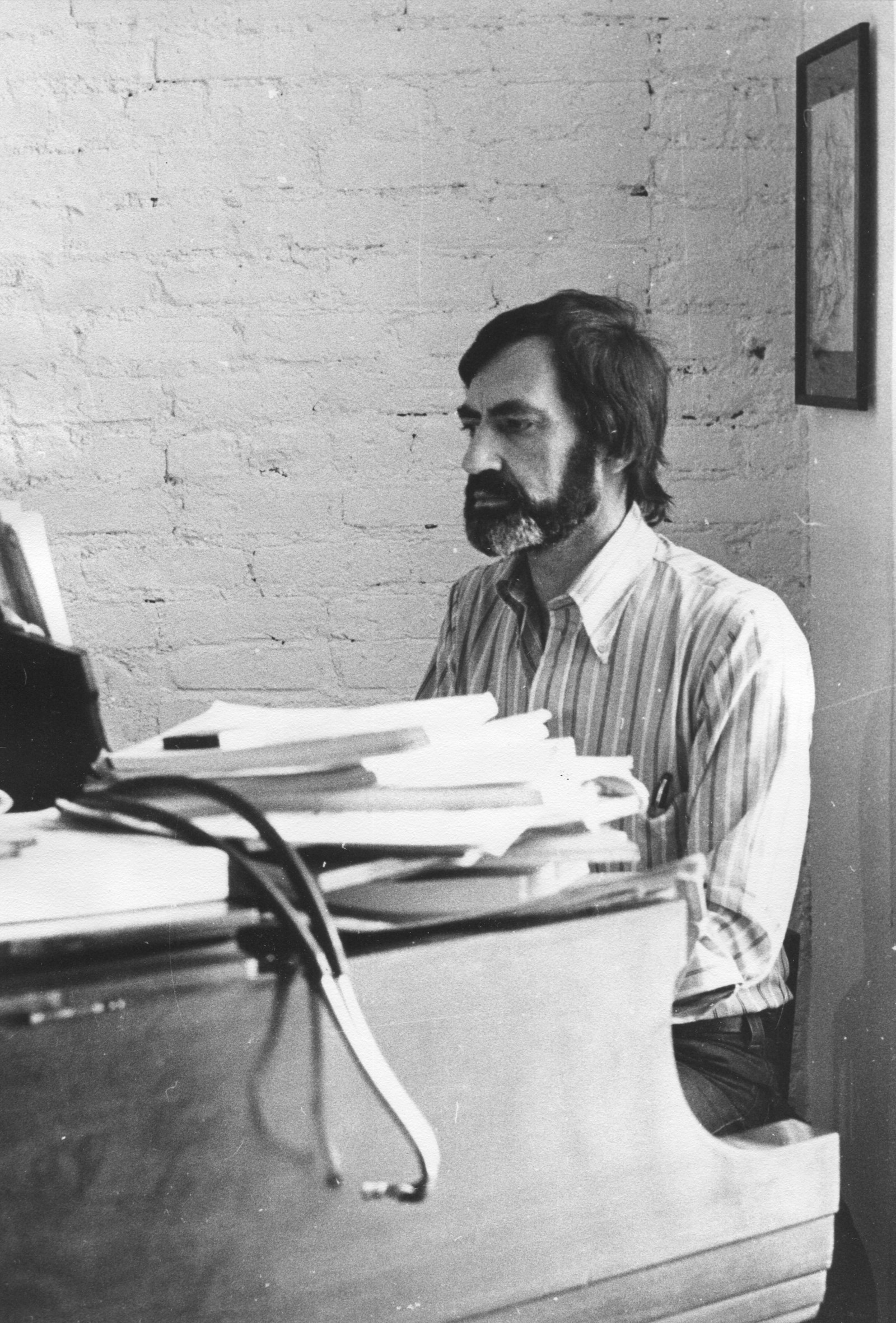

Over nearly five hours, Sonnabend leads BuzzFeed News around his flat from one room to another, pulling out memories, wrestling with everything he has witnessed. His story floods out in a series of startling anecdotes, but among the jolts – some personal, others of historical significance – there were, it seems, two things that kept him going. One of them was his music.

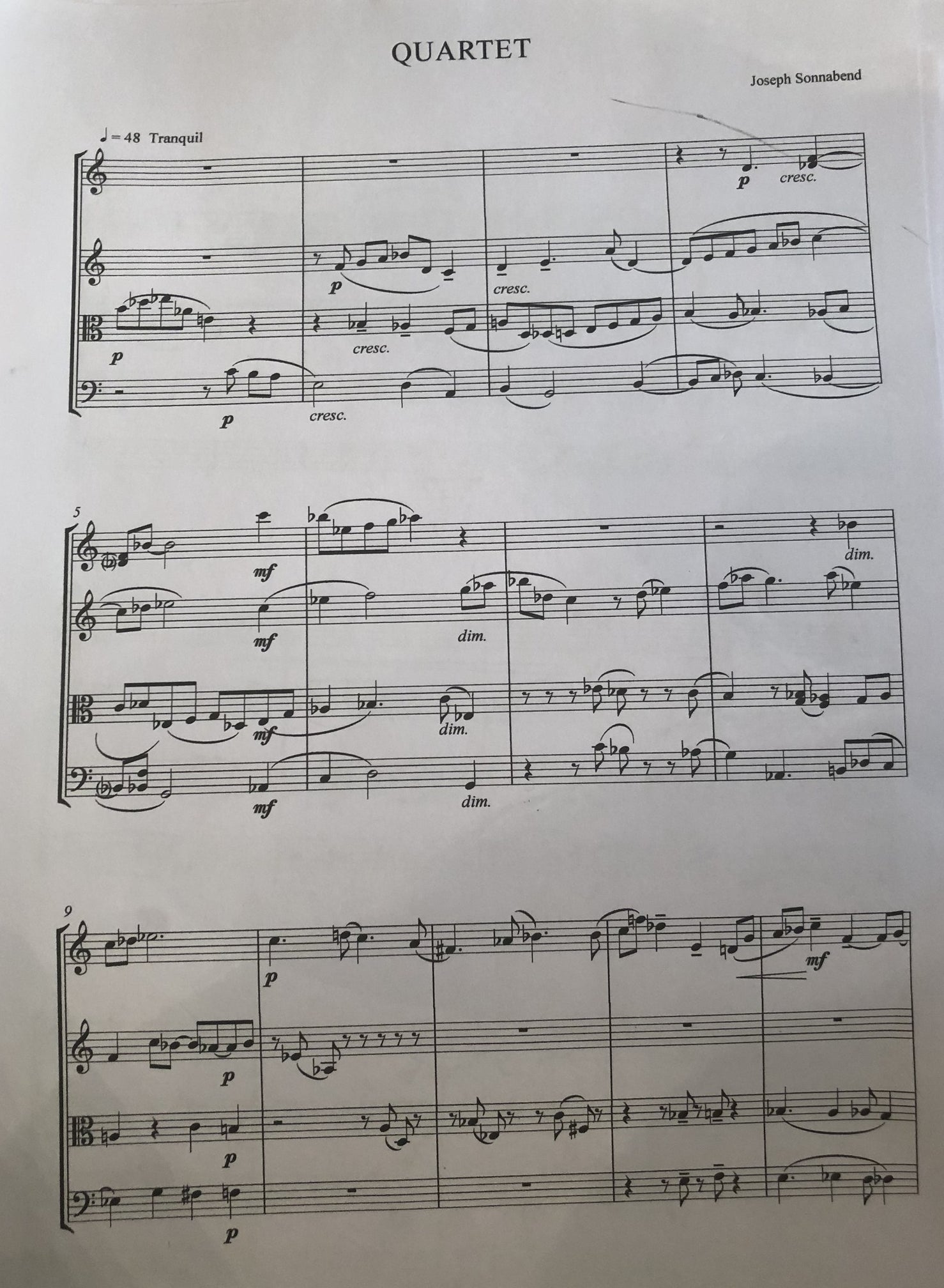

During the 1980s, he would sit at this piano – now in his London flat, then in his New York apartment – writing music in the few hours off he allowed himself each week. As more and more people died, with no effective medicine, no understanding of what was happening, and doctors powerless to save them, composing helped Sonnabend cope.

No one heard his music. He wrote it for himself. But next month the public will be able to listen to his classical pieces for the first time as Sonnabend makes his debut as a composer, aged 85. A series of his works – string quartets, piano pieces, and songs – will be performed across two concerts in London as part of a new festival of culture commemorating the AIDS epidemic.

“It’s so outside anything I might have thought about,” he says of the forthcoming performances. “Quite unreal… If I think about it I’ll probably get a little terrified so will try not to.”

There is a lot, it transpires, that he tries not to think about.

The redbricked, bay-windowed building in which Sonnabend lives sits on London’s Abbey Road, a few metres from the zebra crossing that adorns the Beatles’ famous album cover. He has been in this particular flat only a few weeks, having moved from another in the same block.

He still rents. He does not know how much time he has left to live, he says, and also does not know when his money will run out.

Boxes from the move are still piled high in most rooms. He has no idea what is in them, except for a few that have been unpacked – including the ones with the diaries. He keeps reading the list.

Norman Keating.

“He lived in Staten Island, a drug user, not gay, and worked on the Staten Island Ferry. I remember his mother – I visited him in Staten Island a few times.”

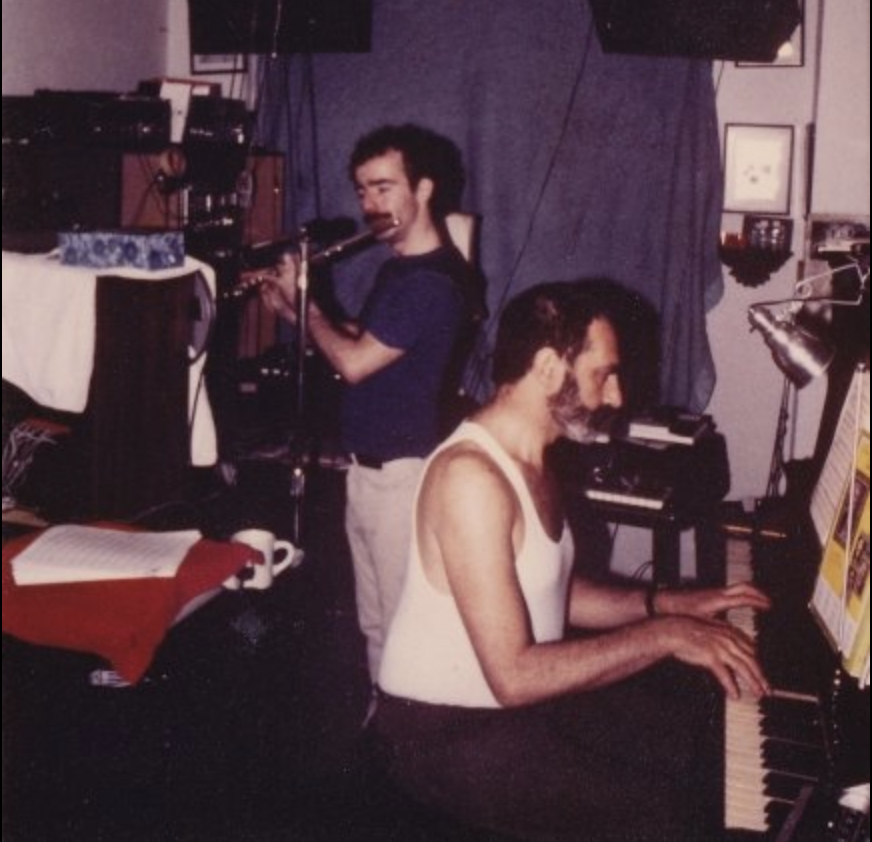

Sonnabend’s finger moves down each name, his other hand rubbing his head as if urging the memories to surface – or perhaps trying to soothe them. He alights on another name – Bobby Blume – that connects the disparate parts of his life.

They used to play music together.

“He on flute, me on piano. He was incredibly talented,” says Sonnabend. “He was a composer, properly trained. He made his living reconditioning instruments.” They would meet at weekends. “Then he got Kaposi’s sarcoma,” says Sonnabend.

This form of skin cancer was exceptionally rare until AIDS arrived. “His face became like a balloon. He couldn’t play the flute anymore.” Although Blume’s lips were too swollen for the flute, he was able to manage the piccolo, and so towards the end, doctor and patient became a different duo to enable him to continue playing.

“Poor Bobby,” says Sonnabend, with a tenderness that offers a flash of something it seems he normally tries to conceal: sorrow.

Bobby was 26.

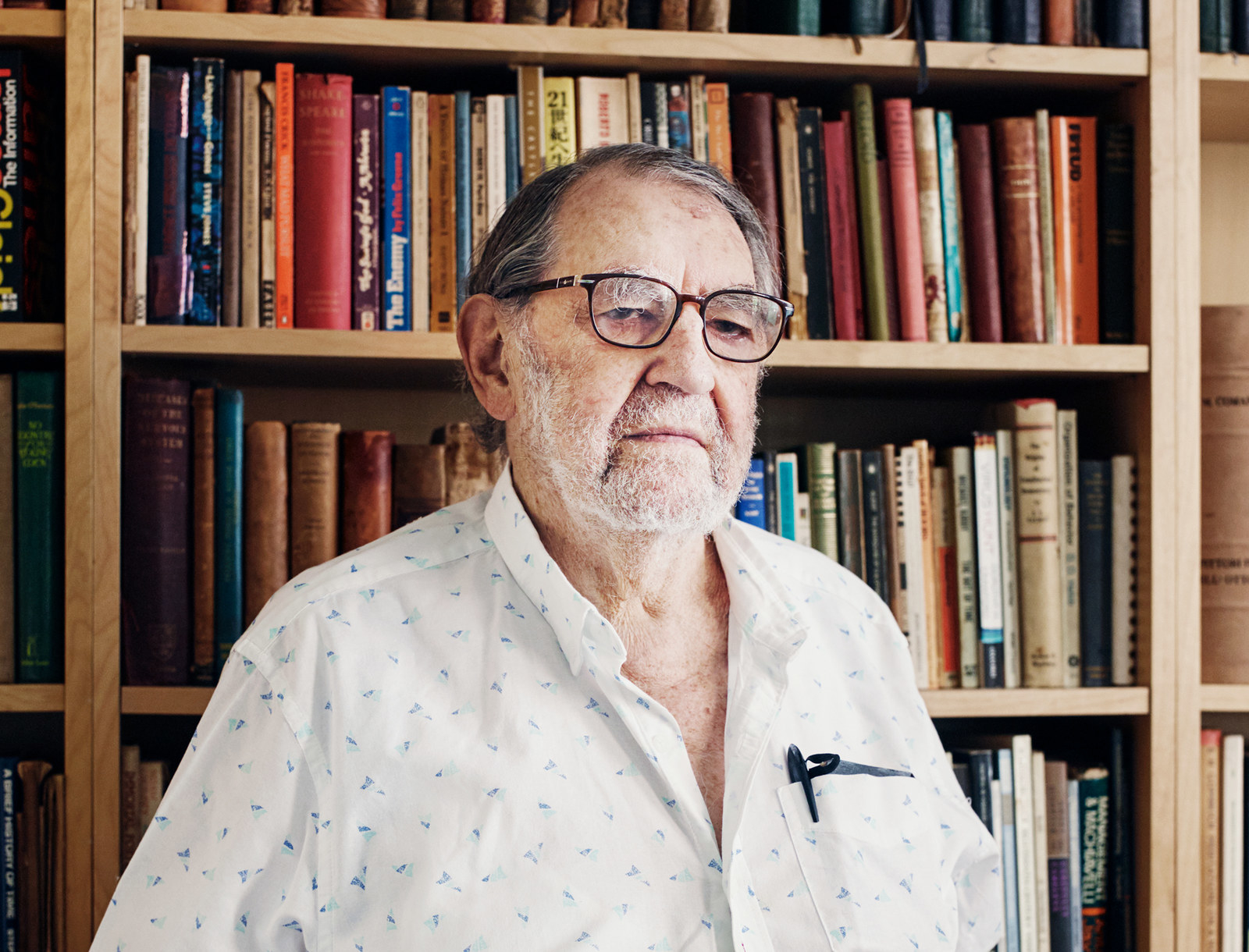

Sonnabend speaks quietly and evenly, avoiding sentiment where possible. His accounts of events are also almost exclusively rational and factual. Any question posed, therefore, that is vaguely inaccurate he corrects, as if contemptuous of imprecision.

Even the fact that for decades he has cut his own hair – Why waste money? he says – seems to offer a clue to his character: Focus on the fundamentals, ignore the frivolous niceties. Today, he eats dry toast at his kitchen table, wears a baggy old shirt, and could not seem less comfortable having his photograph taken. “Much of my life I’ve spent trying to avoid public attention,” he says.

We return instead to the beginning of his life and how it brought him to the brink of the AIDS pandemic.

Sonnabend was born in South Africa to Jewish parents – a doctor and an academic – but raised in Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia) before completing medical school in Johannesburg. Following specialist training in infectious diseases, he moved to the UK and worked for the famed virologist Alick Isaacs.

In the 1970s he left for New York to take an associate professorship at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine. After a stint as a director at the New York City Department of Health, in charge of STDs, and with research grants having dried up, Sonnabend, by then in his forties, decided to open a sexual health clinic in Greenwich Village, near the heart of New York’s gay scene. It was 1978.

His background in infectious and sexually transmitted diseases, combined with this location, placed him in an almost uniquely ideal position to identify what was about to unfold.

“Fate put me at the beginning of this epidemic,” he says. “I saw things in those early years that couldn’t be explained by common STDs: low white blood cell counts, enlarged glands, big spleens, a variety of things. There were too many of them. I even wrote to the city Health Department in 1979 asking if other people had been reporting low blood platelets. I don’t think I even got a reply.”

"Fate put me at the beginning of this epidemic."

He began to see something else: patients with a type of rare pneumonia – pneumocystis pneumonia, or PCP – that further alarmed him. “I was aware of something wrong. I thought it possible that what I was seeing was somehow a consequence of repeated infections with syphilis, hepatitis, the whole gamut of things, because that’s what I was seeing.”

But it wasn’t until he saw his first patient with KS – the cancer that would later engulf Bobby Blume, the flautist – that everything changed.

This patient was called Spencer Beech. Sonnabend remembers his name particularly clearly because Spencer’s boyfriend’s name rhymed with it: Barry Leech.

Beech was anaemic, so Sonnabend sent him for a gastroscopy, to look down into his digestive system for an explanation. The specialist phoned Sonnabend. “She told me the gastroscopy had shown purple lesions in the swellings of this man’s stomach.” Biopsies were taken. “She said, ‘It’s Kaposi’s sarcoma.’”

The gastroenterologist had never heard of this cancer, which typically presents as dark blotches on the skin, anywhere on the face or body. Unknown to anyone at the time, it would become one of the defining symptoms of AIDS. She phoned the National Cancer Institute to enquire who knew about KS and was referred to a dermatologist at New York University called Alvin Friedman-Kien. He told her something extraordinary: More than a dozen gay men in New York City had been diagnosed with KS.

“That was completely unbelievable,” says Sonnabend, who then phoned Friedman-Kien himself. Suspecting that something freakish was upon them, Sonnabend started helping out at the laboratory at NYU: working there in the mornings, seeing his patients in the afternoon.

“Not for any money,” he says about the lab work. “You had to do something. I knew something more grave was going on.”

From 1981, after the New York Times famously first reported “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals”, that gravity came into view, month by month, escalating as cases began to rise. In those early years, before HIV had been isolated as the cause, before people knew how it was transmitted, and before any medication or health campaigns, confusion and panic reigned. By 1984, over 3,000 people in the US alone had died of AIDS.

Sonnabend looks down the list again, flicking page after page. “This, this, this, this, this,” he says as each one, full of names, turns. He finds Spencer Beech on there. And then his boyfriend, Barry Leech, a few pages later. They died within a year of each other.

He stops on another name. “Raymond killed himself.” This was not uncommon in the 1980s once someone had been diagnosed. There was no treatment, only the certainty of dying prematurely and in pain, often rejected by family or friends. Some hospitals refused to take body bags containing those who had died of AIDS. Some patients who were accepted by hospitals were kept in seclusion as nurses left food outside their rooms, afraid to enter. Terror and isolation were the bedfellows of young men as each opportunistic infection gripped.

Sonnabend mentions another man on the list, called Michael, who was “the brother of somebody I was involved with – my brother-in-law.”

He reads more names; each one takes him back three decades. A Catholic man called Declan who “had a seizure and was taken to the Catholic hospital by the ambulance and they hid him [in the hospital] because he was gay. They didn’t even let him die in peace.”

Another patient, Chip Edgerton, he recalls, smiling, “used to walk round as a construction worker. He wasn’t a construction worker. It was his gear, with hammers hanging from his belt.” This was, after all, not long after the Village People. “That sticks in your mind!” he says, raising his voice as if trying to lighten the mood. It does not last.

“I have tried to dull the memory of it all,” he says. But the experience for doctors like him at ground zero of the epidemic, floundering amid the disease’s cruelty and stigmatisation, was overwhelming.

"I have tried to dull the memory of it all."

“People are dropping, it’s a mystery disease, you’re challenged as a microbiologist to try to find what’s going on, getting involved in research, mobilising people and the reality is every day seeing 20-30 people facing horrible things and dying.” But no one could stop to absorb what was happening.

“If you live in a situation that demands your attention day to day you don’t have time,” he says. “You can’t wallow basically. You don’t have the latitude. As a consequence I think it helps you deal with things.”

It bled into his private life – Sonnabend restricted his sexual relationships.

“I thought I had to stop. I thought that maybe I was contributing to…” His voice dwindles to nothing. “Nobody knew what was going on in the early days.” How did he navigate intimacy?

He emits a sort of dark cackle. “I was terrified,” he says, before scoffing at the stupidity of the question. “What do you think?” Despite his precautions, nothing could stop his lovers falling ill.

“Every man I was involved with died,” he says, quickly, before moving onto something else. As well as relationships with men, Sonnabend has been married to a woman and has children. He says he does not know what his sexuality is. It does not seem to matter to him.

The HIV test wasn’t introduced until 1984, and not rolled out widely until 1985. He advised his patients not to have it. “There was no treatment so what was the point?” he says. He also knew that the risk following such a diagnosis was suicide.

Sonnabend himself did not have an HIV test until the 1990s. It was negative. But until then, he says, “every time I saw a spot on my skin… you can imagine… I shared that [terror] with everyone else.”

He continued to focus on work, his patients – visiting them at home, giving them his home landline number, paying for their tests and treatments, winning their trust, supporting their partners. They stopped him sinking.

We move into a room where his computer sits. He starts to play a series of audio files that he has transferred onto it. They are recordings from his home answer machine in the 1980s. Some are fairly mundane: his receptionist wishing him happy birthday, a patient he used to play four-handed piano with wanting to meet up that evening.

But what also crackles through the speakers are the voices of his patients needing help in their final days. One that reverberates from 35 years earlier is a young man’s voice, slurred, slow from heavy medication, gravely ill.

“BEEEEP. It’s Dennis. I was at the hospital and they released me. Please call me on... It’s an emergency. Please. Please call me, Joe. Thank you.”

Sonnabend turns back from the computer. “If you have all of this going on you can’t dwell on your own… you just have to keep moving. You just swallow it.”

But there was something else that helped beyond stoicism: music. Sonnabend had learned the piano as a child but initially hated it.

"You just have to keep moving. You just swallow it."

“Then when I was 12ish I suddenly found the music absolutely engrossing.” What did it give him? “I can’t immediately answer that,” he says, not one for introspection. He took up the organ too. What, then, did playing and composing give him in the 1980s during the AIDS crisis? This time he knows.

“It was like walking into another world,” he says. “Just shedding all the preoccupations of my job. It provided me with a sort of contrast, an activity away from all that went with that particular period in history.”

Beyond his music and his own patients, Sonnabend set about responding to the crisis for as many as possible, in ways that would both rupture and secure his reputation.

In May 1983, along with two gay men he knew, Sonnabend helped author the first booklet for safe sex in the era of AIDS, “How to Have Sex in an Epidemic”. It was the original public health advice to recommend using condoms to protect against the virus.

Today this sounds obvious. Then, because many in the medical community thought that this “killer virus” worked quickly after even one exposure, some felt that even condoms couldn’t be recommended in case they broke. But Sonnabend had a different and contentious theory: that whatever was happening was the result of sustained, frequent exposures.

In the end neither was correct. Now we know that the virus is quite weak, and that the incubation period between acquiring it and dying is several years. Although incorrect in its reasoning, Sonnabend’s advice provided the blueprint for safer sex that is still used today.

On the recommendation of a lawyer patient, later in 1983, Sonnabend also founded the AIDS Medical Foundation in an attempt to understand the disease, and find a treatment. It is now called amfAR (American Foundation for AIDS Research) and is one of the world’s largest funding organisations for HIV research.

But for Sonnabend, the original intention – to fund studies from new, emerging researchers – has been disbanded in favour of supporting those whose pedigree is already established. “In other words, people who are already funded.”

This is not the only development in that organisation that still irks him. As an aside, Sonnabend tells a story about its early days that encapsulates not only the chaos of the time, but also the knife edge on which history pivoted.

In 1985, Sonnabend hired an activist called Terry to be a fundraiser and publicist for the foundation. “And one day I walked into our office and I picked up a phone that was ringing.”

What led to that call changed the course of the response to the epidemic.

“It was one of the [TV] networks saying they’d received a press release [from the foundation], saying that there was an impending heterosexual epidemic. And I said, ‘That’s bullshit, where did you get that from?’”

Sonnabend soon found out. Terry told him that he and the foundation’s other cofounder, Mathilde Krim, cooked up the press release saying, “AIDS is about to swamp America.” They bypassed Sonnabend before sending it out.

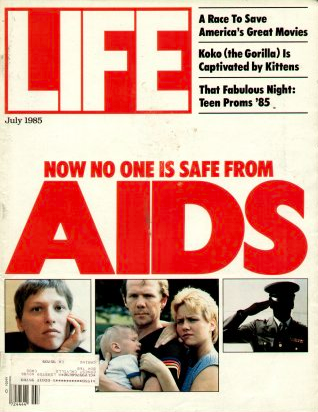

Shortly after, Life magazine had emblazoned on its cover a warning that terrified the country: “Now No One Is Safe From AIDS.” It pictured a young, white, heterosexual couple with an infant. The article inside said “the AIDS minorities are beginning to infect the heterosexual, drug-free majority” and claimed, “From one to three million Americans may be harbouring — and passing on — the virus without symptoms.”

This was unfounded. The scale of the imminent heterosexual epidemic had been grossly overstated. It took another 20 years to reach those numbers. But it was too late; the message hit, fuelling panic, and, in doing so, fuelling something else: more donations.

Sonnabend resigned from the foundation in protest at being sidelined, furious that such inaccuracy would be promoted by his organisation.

“Now they’ve become huge,” he says. “They give out £100 million a year. Something that started in my office.” He seems at once hurt, still, at being shut out and deflated that his intentions for it changed drastically.

Such battles at the time, however, only compounded the stress from all the dying, making the solace of music yet more necessary. “I wasn’t conscious of it,” he says about the instinctive need on those Sundays to sit at his Steinway piano. “It was entirely personal. There was never any ambition for public performance.” But that need sustained as the years, deaths, and infighting grew.

In 1987 Sonnabend also cofounded the PWA Health Group, which was the first and largest to bring new, but not yet approved drugs, to those with AIDS. It was an idea soon copied by Ron Woodroof (and others) whose homespun drug distribution service was turned into the Hollywood movie Dallas Buyers’ Club.

Sonnabend set up the PWA Health Group (now called People With AIDS Working for Health Inc.) with an activist called Tom Hannan. But it is Hannan who provides another snapshot into the fractures of Sonnabend’s life.

“He threatened to kill me,” says Sonnabend. “He asked me to give him a prescription for Valium but he wasn’t my patient and I refused. He got angry. There was a message on my machine threatening my life. I didn’t sleep in my home that night. In that climate everything was on edge.”

No more so than when the drug AZT – previously used for cancer, then believed to be effective in combating HIV – resurfaced in the late 80s, further igniting fury against Sonnabend. Activists exerted significant pressure on the authorities to speed up the normal processes involved in testing drugs.

But in the speed it ended up being prescribed at doses so high it caused extreme toxic side effects – and it did not stop the dying. Sonnabend wrote extensively about the flaws in the evidence but so desperate were doctors and patients for anything that might save them, he was ignored and castigated for his opposition.

“I was subjected to a tremendous amount of hostility,” he says. “I became aware of the shortcomings in the scientific response and antagonised many scientists by pointing things out.”

In some ways, he says, “AIDS has been the joke of science. There’s much shoddiness involved in HIV clinic research. There have been ridiculous trials – the most egregious example is AZT – but to this day have any of the established scientists stood up and revisited it and said, ‘We were wrong’? No.”

The anger over his opposition to AZT was only exacerbated by his refusal right into the 1990s to accept the prevailing belief that HIV was the sole cause of AIDS. Sonnabend became synonymous with what was called the “multifactorial” theory: that a range of factors combined to produce the symptoms of AIDS. It led to his views being inaccurately reduced to those of an AIDS denialist – the fringe group that denies that HIV causes AIDS and also denies that today’s combination therapy of antiretrovirals is effective.

In this, as with AZT, Sonnabend wanted to wait until the evidence was unequivocal before supporting anything – a standard position for scientists. But this was not a standard time. Patience was, for many, unaffordable.

Sonnabend also had to contend with discrimination simply for treating people with AIDS. The office for his clinic in Greenwich Village had been turned into a co-op, with doctor’s offices on the ground floor, and residential apartments above.

“My lease expired and they wouldn’t give me a new one,” he says. “They [the members of co-op board who owned their apartments and ran the building] didn’t want my patients going through the lobby; they thought that people with AIDS – gay guys – would reduce the value of their property.” The chair of the board told Sonnabend this to his face.

“My lawyer immediately saw a case. So we brought action against the co-op.”

"They thought that people with AIDS would reduce the value of their property."

He won. It was the first HIV/AIDS discrimination case in the United States and set a precedent. The co-op still tried to push him out, though. “They offered me money to leave and if I didn’t then they would reduce the amount month by month.”

Sonnabend refused to budge. He waited month after month until the sum offered dwindled to zero. Then he left.

“It’s too unpleasant to think about,” he says. His patients, the people who carried him through the epidemic, moved with him to his new office.

Is there one person whose death hit him hardest? Sonnabend thinks, looking round the room at the piano and the boxes, eyes darting about.

“There was one,” he says. “Called Michael. He was shy, not very confident and so for whatever reason I took him under my [wing]. I felt protective towards him and gave him a job as my receptionist.”

He explains that in the early days of the foundation they had no money and, with Sonnabend often not charging patients – his only income – eventually he could no longer afford to pay Michael’s wages. Michael then worked for a while elsewhere, but, says Sonnabend, “He became demented. He used his savings on hired home help for as long as his money lasted.” His family had rejected him.

When Michael’s savings ran out, he ended up in a hospice. There he developed pneumonia and was sent to the emergency room. “I went to see him and found him in a cubicle gasping for breath,” says Sonnabend. “He was terrified. He was obviously dying and he wasn’t being attended to. Left alone to just die. Abandoned.”

He stops for a moment and for once allows himself to sink into the memories. “I got the attention of the doctors but there was nothing they could do. The horror of that… Feeling totally frustrated and helpless. Somebody dying under your nose and not being able to do anything…”

In so much that Sonnabend says, this sense of frustration surfaces, mostly, however, about not being unheard: His initial enquiry about low platelet counts, his warnings about AZT, the original missions of his organisations.

“I feel incredibly sad about missed opportunities,” he says. “If I hadn’t been maligned in my efforts I think we might have achieved a little more a little sooner.” Having worked in immune suppression as well as infectious disease before AIDS struck, Sonnabend also advised in the 1980s that drugs to prevent pneumonia should be administered.

“It wouldn’t have saved lives but we could have at least prevented people dying this horrible death from PCP – a suffocated death,” he says. His tone changes, as if detaching.

“I tried my best,” he says. “No one listened.”

The irony looming is that Sonnabend will have a captive audience next month, listening to the music he wrote when what he really wanted was for people to listen to his warnings. The concerts will be held at London’s ornate Fitzrovia Chapel, in what was once the Middlesex Hospital, and the site of Britain's first Aids ward. Part of the Aids Histories and Cultures Festival, which is being funded through GoFundMe donations, the forthcoming performances seem to baffle Sonnabend.

“I just thought nobody would be interested,” he says. “I didn’t think anything I did would ever be performed.”

He plays another audio file from the computer, this time a recording of one of the rehearsals of the soprano singing a song of his. She is accompanied by the piano: low, repeated funereal notes, crunchy late-19th century harmonies atop, as her voice soars. The words are translated from a Japanese poem.

“Dew on the tips of branches, slowly falling to the roots, just as we delay in this world.”

"I didn't think anything I did would ever be performed."

Despite all the controversies, Sonnabend is now regarded more simply as a leading pioneer in the history of HIV/AIDS. One further irony is that in 2000, amFAR, by then the huge foundation he had long since left, awarded him its inaugural Award of Courage, saying he made “Olympian contributions to the fight against AIDS during the years when this was a lonely and thankless endeavour.”

I ask again how he feels about the prospect of hearing his music finally performed. It is unclear whether his answer refers to this, or anything else that happened 30 years ago. He looks out the window, pulls his glasses off and replies, matter-of-fact:

“I’m still blocking it out.”