Loud banging on the front door marked the beginning of the end. It was the police. One of the neighbours had complained about crazed screaming coming from next door.

A disturbance like this, at 2pm on a Friday, was unusual in Belsize Park — one of the wealthiest areas of north London. The officers assumed it was some kind of domestic dispute.

They had no idea what they were about to discover.

The noise, it transpired, was not an abusive spouse but the deranged shouting of a man high on crystal methamphetamine. And the man who opened the door to the police on that June afternoon in 2015 was his dealer. His name is Cameron Yorke.

Yorke is middle-aged, urbane, and educated; a travel journalist and author; a former model and businessman from New Zealand.

But in just a few months he had abandoned the confines of respectability and become instead the kingpin drug dealer to London’s chemsex underworld.

More than 3,000 gay men were regularly buying all the narcotics they needed for days-long sex parties from Yorke: crystal meth, GBL, Viagra, mephedrone, cocaine, cannabis, and MDMA.

His clients, he says, included A-list celebrities, high-ranking police officers, judges, doctors, chefs, teachers, and lawyers. Sometimes hundreds would come to his home during the course of one night — some staying for group sex, many needing his help to inject the meth into their veins.

Yorke’s suppliers had scant access to the gay men who would buy their drugs, until he emerged on the scene. He became the gateway.

When the police arrived that Friday afternoon, his fast talking helped keep them on the doorstep as long as possible. After several minutes answering their questions, Yorke thought that the instructions he had given to the naked men in his living room just prior to answering the door — to hide everything — would by now be enacted.

He was wrong.

The police insisted on entering. They walked into a chemsex party in full flow: half a dozen hastily clothed men surrounded by pipes of crystal meth, lines of white powder, a plate of cocaine, needles, joints, vials — a sea of drug paraphernalia. One man was unconscious. Another was sweating profusely from a huge injection of meth just minutes earlier. And a drum containing 5 litres of GBL was sitting in the kitchen.

But it would take another 10 months, another arrest, and a man dying in his living room before Yorke was finally stopped and finally imprisoned.

Today, he reveals to BuzzFeed News how everything escalated, and how it all unravelled: his life, his health, his relationship, sanity, money, and finally, freedom.

What no one knew was who lurked in his background; what linked an elderly, dying man thousands of miles away to the scene in his apartment that day. And how this refined, successful writer could have sunk so far or risen so quickly to become the puppeteer of Britain’s chemsex scene.

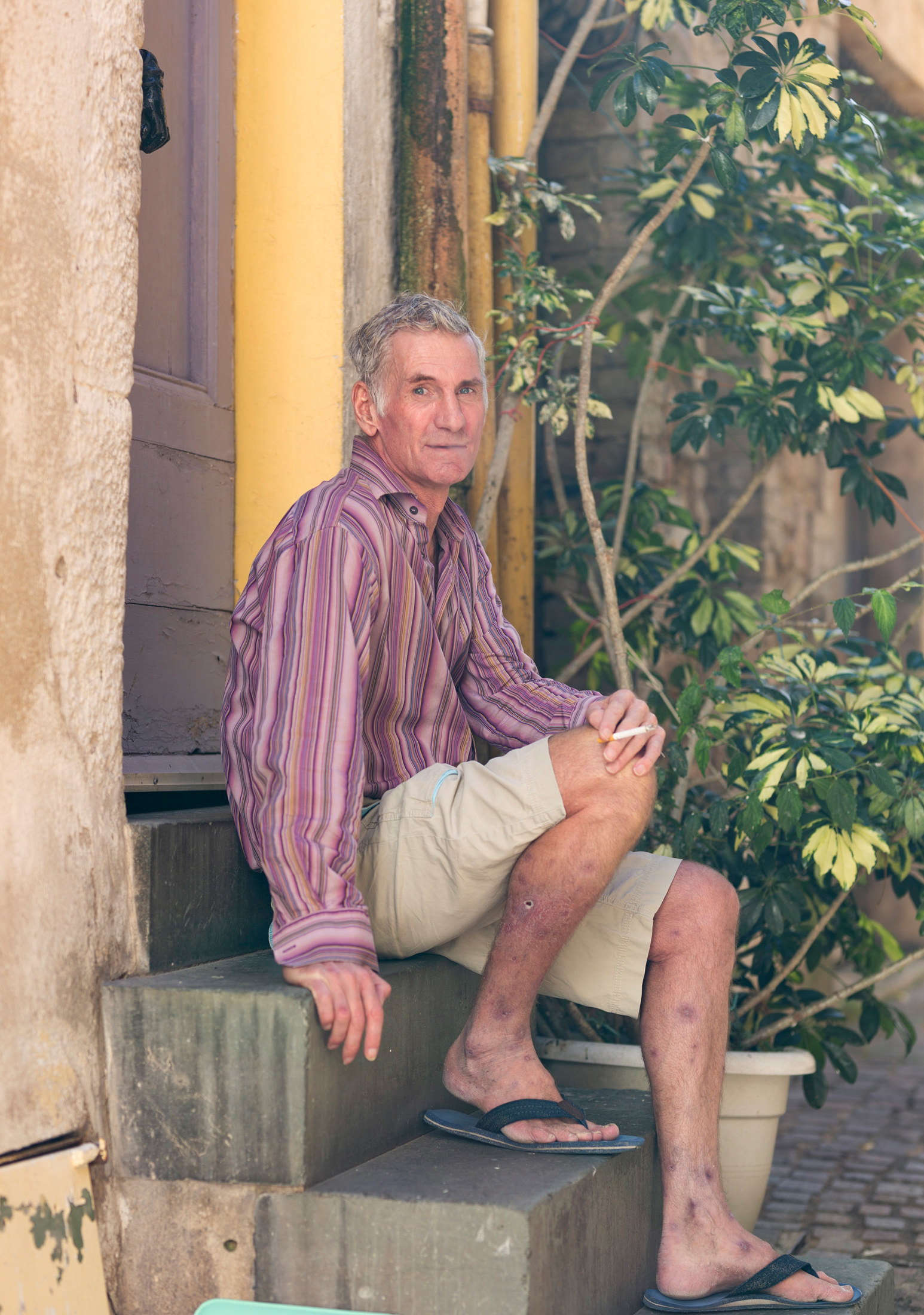

“Five years ago if someone had said to me that I would have done the things I’d done I would have laughed them out of town,” Yorke, 52, tells BuzzFeed News now, sitting in his modest apartment in the south of France, where he has been living for the last few months.

He talks swiftly and loudly, smoking cigarettes. He laughs at the most diabolical memories. Each laugh exposes missing front teeth. He rants at times, furious at the police, the prison officers, the Home Office officials who deported him, while ultimately blaming no one but himself.

His account offers an unprecedented bird’s-eye view of the chemsex drugs scene, revealing how one step into this unknown world can slide rapidly into spiralling criminality and destruction. But it reveals, too, how many people, simply lonely or vulnerable, are drawn in, only to find themselves further victimised, sometimes addicted, and often traumatised.

As BuzzFeed News has previously reported, many on the chemsex scene, so detached from the boundaries of the outside world, find themselves sexually assaulted, raped, psychotic, suicidal, suffering overdoses — or witnessing many of these. They often tell no one. The authorities, meanwhile, are scrabbling to keep up.

Yorke is still trying to make sense of his descent.

At first, it sounds like a gay version of Breaking Bad, the television drama about a high school chemistry teacher who becomes a major supplier of crystal meth.

But as he talks it soon becomes clear how different Yorke’s story is.

This is all real.

Cameron Yorke’s accent, bellowing out of a reedy, nasal voice, is still resolutely New Zealander. But by the time the British government had deported him back to his motherland last year, after 19 months in jail, it had been 30 years since he had lived there.

One Sunday morning in the summer of 2017, Yorke stepped off the plane in Auckland with £112 in his pocket. It was all he could save over three months from his £12-a-week kitchen job in prison. He had nowhere to live, no job, no friends, and a criminal record. “I was petrified,” he says.

There was only one person still left in New Zealand who might be able to help him: his father. But there were two problems.

“We hadn’t spoken for over 20 years,” he says. “And he was dying of Alzheimer’s.”

The story of Cameron Yorke begins and ends here with his father.

Yorke grew up in Hawke’s Bay, a beautiful coastal region on New Zealand’s North Island. It was still illegal to be gay. “Very parochial,” he says, sitting on his couch in a suburb of Cannes, eyes darting about restlessly. The Yorkes were a conservative farming family.

After a stint modelling in Tokyo aged 19, he ran away to Australia, met a young woman in Adelaide, and married her. But by the end of his twenties, the relationship had collapsed. Yorke moved to Melbourne, began exploring his homosexuality, and came out to his mother, by then separated from his father. Yorke overheard her on the phone later that day: “You must come to lunch next week — my gay son is home!”

His father was less delighted. Yorke planned to tell him the following day, but his sister beat him to it. She rang Yorke to relay the reaction. He says: “She said, ‘Don’t bother going to see your father. I’ve already told him and you’re not welcome in his house.’”

Yorke and his father did not speak until he was deported back to New Zealand. Instead, he spent the next 20 years knowing he was unwanted — rejected for being gay.

“I had something to prove,” he says, “that I would make it on my own and be successful no matter what.”

Initially, he fulfilled this in the most obvious, conventional fashion — he set up an interiors company, with his first boyfriend, which grew to a chain of three stores, all in Australia. It taught Yorke the fundamentals of profitable business: great products, the right price, how to market them. But after eight years they split up and sold up.

Needing a change, he began travelling around Europe on the proceeds and writing a book about his adventures that caught the attention of travel editors. Soon he was writing for Condé Nast Traveller — the ultimate in high-end travel journalism — and a range of other magazines.

In 2007, Yorke finally arrived in London — and the flat in Belsize Park. He began branching out into documentaries with a new boyfriend he had met. We will call him Giovanni. He would become the trigger for Yorke's downfall.

By early 2014, “We ended up producing two documentaries at the same time, and entered them for the Cannes Film Festival,” says Yorke. “But three days before we left for Cannes, he packed up and left.”

Giovanni walked out of both the relationship and the film projects. He also, says Yorke, “drained the bank account”. Staff on the documentaries still had to be paid. “So I came back from Cannes with not a cent to my name, thinking, What the hell am I going to do?”

Yorke was 49, heartbroken, and broke.

Needing support, he phoned a friend, Mark, who invited him round to his house in Chiswick, west London. Sympathising with Yorke’s news, Mark made a suggestion: “You’ve had a terrible time. Why don’t we order in a whole load of drugs and get fucked up?”

Yorke was not really in the mood. He also had only ever dabbled in more traditional drugs like ecstasy and cocaine. “This will be fine,” Mark told him. “It’ll take your pain away.”

The delivery soon arrived.

“He pulled out these needles and started filling them up and I was like, ‘What the fuck is that?’” says Yorke.

It was crystal meth. Injecting it is referred to as “slamming”. Mark reassured him, reminding him that he was a trained nurse and insisting Yorke would love it. The needle sank in. The drug — notorious for skyrocketing sex drive and energy — took hold. Yorke and Mark stayed up, high, having sex, and as they started to come down Mark asked if Yorke had enjoyed it. “It was amazing,” said Yorke.

“Good,” Mark replied. “Because I’ve invited five other people to come over in the next hour and we’re going to have a party.” It went on for three days. Yorke had only ever been in monogamous, long-term relationships. Afterwards, he says, he was conflicted: horrified at himself but unable to deny how thrilling it had been.

From that day, Yorke’s introduction into chemsex developed rapidly. He started using Grindr, the gay dating app, to find others in his area wanting sex on meth, GHB/GBL (usually just called G), and mephedrone — the trinity of chemsex drugs that heighten and disinhibit.

“A couple of weeks later I had met local people who were all doing it,” he says. “Belsize Park was like a den of iniquity. If you walked down the street at 10pm you could see all these queens bed-hopping across the street.” Some were as close as a few doors down.

Yorke is still trying to understand what led him further and further in.

“I was mourning the loss of a relationship,” he says. “I was worrying about the fact that I was 48 and therefore ‘on the shelf’ and not attractive any more, so it gave me validation, this feeling of inclusion and acceptance: that I was still attractive.”

The men he was meeting were often professional. Some, he says, worked in embassies, others senior in the police, all convincing Yorke of one thing: that “this was normal,” he says.

So when a couple of months later, in the autumn of 2014 — with Yorke still broke — a friend made an outlandish suggestion, it made complete sense.

“The stuff you get from your dealer is amazing,” he told Yorke. “So why don’t you just sell drugs to a local group of a few of us, and make a bit of money between now and Christmas to see you through?”

Yorke was smoking crystal meth at the time. “It seemed like the most normal thing in the world,” he says, with his palm gesturing out as if showing a visitor through to his gracious drawing room.

It was only supposed to be for a few weeks. It lit the fuse to a bomb.

Yorke’s supplier had the purest meth and G around. So when Yorke acted on his friend’s suggestion and started selling it to a handful of nearby friends, they were immediately taken.

“People loved it,” says Yorke. “Everyone had been having trouble getting good-quality stuff and being given half a gram instead of a full gram — ripped off. The minute I started to supply good stuff at proper prices, all of a sudden they told their friends, who told their friends, who told their friends.”

Word grew so quickly that Yorke could scarcely fulfil the demand.

“Within three months I had over 1,200 clients,” he says.

But because he hadn’t planned any of it, he had no infrastructure set up to hide the mass selling of illegal substances: no security methods, no secret locations. All the men just came to his house.

“On a Friday I would have 350 people beating a path to my front door to pick up something for the weekend,” he says. At any one time, “I had sometimes 30 people in my sitting room waiting at the dispensary to pick up their drugs.” Yorke was still taking the drugs himself, he says, ensuring the extraordinary world he was lowering himself into appeared ordinary; preventing him from stopping.

The more he sold, the more he needed to buy from his supplier. From his background in retail, Yorke knew what this meant: He could haggle.

“Originally, I was buying at quite expensive prices, but then I started saying, ‘Listen, I’m buying in volume now, so you need to beat the price down.’ In the end I was paying £35 a gram for crystal meth and selling it for £150, because it was top-rate stuff.”

He knew also from his previous business that the way to expand is to reinvest: The money he was making he would use to buy larger and larger volumes of product. He then expanded what one might call the product range.

“I was a one-stop shop,” he says. “I had pipes, lighters, Viagra, crystal meth, ketamine, trips, hash, MDMA, pills, GHB. I never had less than 200 grams of crystal meth.”

As well as goods, he provided a service for these mostly professional men unseasoned in the art of intravenous drug use.

“I went and did a course on safe injecting and became an administrator,” he says. “I would have 20-odd people in my house, 12 of whom would want to slam, so I would line them all up with their 12 little needles, and then I’d slam them one after the other.”

Yorke’s attempts to justify his actions first appear at this point. “I couldn’t get myself out of it because there were so many people dependent on me,” he says, as if it were a public service like any other.

With the meth coursing through them and every other drug available onsite, Yorke’s clients would then initiate spontaneous sex parties in the apparent safety of his front room.

“I’d turn around and be like Nigel-no-friends, because everyone would have paired off and I’d be sitting in the corner filing my nails,” he says, laughing, before quickly admitting that he still had sex with many of them.

But as the months rolled on, he says, the sex became less alluring for him. He began to focus, mostly, on the business.

“I just built it up and up,” he says, “and of course the suppliers were straight, so they didn’t have an ‘in’ with the gay community and I was providing the gay community with everything.”

Within five months, he had 3,500 clients. Money piled up. He had become the go-to dealer for London’s chemsex users: the epicentre.

“It was like a roller coaster I couldn’t get off,” he says, his eyes looking panicked at the memory. “It started to spiral out of control. Even if I just shut everything down for the night, the next day I would have 300-odd voicemail messages screaming at me because they couldn’t get the drugs.”

The psychological distortions mounted. Yorke says there were so many men reliant on him for their highs that he saw it as his “moral obligation” to ensure they had the purest drugs and a safe place to take them, and that they were injecting themselves properly. Even now it seems this self-justification lingers — despite everything that followed.

“I don’t think I acted unethically throughout the whole time. I was always concerned about the welfare of the people buying the stuff,” he says, adding that he is “not proud” of what he did — but also not ashamed. “I’m just as much a victim of it as so many other people who’ve got involved with it.”

His apparent one-man harm-reduction centre, however, was all still taking place in his home in Belsize Park. The scenes he witnessed there became increasingly unhinged as orgies and drug-induced psychoses entwined.

It wasn’t simply “guys fucking like rabbits for hours and hours on end with multiple partners”, he says, but “people getting into a state where they thought they needed to pull up the tiles of my bathroom to dig their way to China to escape, or thinking Princess Charlotte was having a cocktail party in the bottom of my wardrobe.”

Yorke would talk to the men as they entered his flat in search of oblivion.

“There were some of the most vulnerable people in gay society,” he says. “People who had had a trauma, the loss of a loved one or a breakup, people who were unable to come out, or who were escaping. And that’s what it [chemsex] targets. If you’re a happy, well-balanced, sane person you don’t need those sorts of drugs.”

All of which leads to Yorke discussing a particularly vulnerable guest whose need for escape and comfort still troubles him: George Michael.

“I knew him quite well,” he says. “He was very much like everyone else in that situation. He was heavily into crystal meth, he would slam, he would also smoke. He was just depressed. It was so sad. He was such a lovely man, but like the rest of us, when he took those drugs it all went away.”

Sometimes Yorke would go to Michael’s house; other times, Michael would come to Belsize Park — not far from his home in Highgate.

“He would ring up at 2am and say, ‘What are you doing?’ And I’d be sitting there, wired, unable to sleep, waiting for people to ring up with their next orders, so he would come over and we’d have a few pipes or whatever. Sometimes it would be 6am and he would drop in and we’d have a couple of lines of coke. There was always something missing [in him]. He was constantly…I think lonely more than anything. And that was one of the saddest things I saw.”

But by the time Michael died, on Christmas Day 2016, Yorke was in jail. “One of my biggest regrets of being in prison is I might have been able to do something if I’d been there for him,” he says. The coroner concluded Michael had died of natural causes.

By the time the police arrived on that Friday afternoon in June 2015, thanks to the unhinged shouting of a client, Yorke had been dealing for over a year. But even with all the evidence laid out, the police, says Yorke, were so ignorant of chemsex drugs that they missed what was there.

“There was a 5-litre drum of GBL in the kitchen and they climbed over it to get to the fridge to see what was in there — and left the GBL sitting in the kitchen.”

Regardless, the officers arrested Yorke and took him to Holborn police station, where he was charged. The next day he was released on bail.

The trouble was, says Yorke, they also confiscated his passport, thereby preventing him from returning to his other mode of employment: travel journalism. So he continued dealing — to tragic effect.

It was on the night of Sept. 10, 2015, just three months after the arrest, that a man named Mohammed Saleem arrived at Yorke’s apartment. Saleem, a hairdresser, was separated from his wife and children. He had met Yorke on Grindr a few weeks before. There were several others already at the house, mostly passed out, when Saleem arrived.

“We’d done some crystal meth,” says Yorke. “And then he just pursued me all night for sex. I couldn’t get him out of my apartment. It was just foul, and in the end I realised I wasn’t going to get any relief if I didn’t just give in.”

Afterwards, Yorke told Saleem to “fuck off” and heard him walk into the living room. Having been awake for three days, Yorke then fell asleep. The next morning, he rose late for an appointment and went straight out. It was only that afternoon, when he returned home with a friend around 3pm, that he saw Saleem.

“I found him dead in my sitting room,” he says — an overdose. “He was squatting down beside the sofa with his elbow on the sofa.” Yorke had never seen a corpse before. He phoned the ambulance. The paramedics, says Yorke, found a bottle of GBL in Saleem’s pocket. Yorke says he had not sold him this and did not know he had taken any.

The police came and questioned Yorke for several hours.

“In a way I wasn’t sorry that he died,” he says. “But I was horrified that I could get myself into that situation and that I would be powerless to stop it. And that I had no control over what people were doing.”

A local newspaper report at the time reveals that Yorke failed to attend the inquest into Saleem’s death to give evidence. As he talks about this period, he lurches between seeming completely disconnected and traumatically horrified, as if even now he has not calibrated it.

By November 2015, Yorke’s mental state was deteriorating.

“I was at a point where I just didn’t care about anything any more,” he says. “I wanted it all to end. I convinced myself that the world would be a better place if I wasn’t there.” He describes the methods by which had decided to kill himself.

“I planned it,” he says — twice. “But both times friends turned up before I was about to do it.” He shrieks with laughter.

It wasn’t only the drugs, the death, and the loneliness that pushed him under, he says. “It was a combination of stuff that had been under the surface for a long, long time.”

When he was arrested a second time, in early February 2016, Yorke could barely care less. This time, he says, the police were apprehending him on immigration charges, as without citizenship or leave to remain, he was repeatedly breaching his visa. “I’d become slack and lazy and there are drugs all over the apartment, so they found everything.”

He was remanded in Pentonville prison, awaiting his court appearance. His cellmate was a huge, 62-year-old man involved in the drug trade who had “taken a machete” to someone, he says, “basically an axe murderer. So, for a little middle-class boy from New Zealand who had made a living as a travel journalist, all of a sudden it was a huge rude awakening.”

Yorke pleaded guilty. In April 2016, after giving up the names of his suppliers, he was sentenced to five years in prison — significantly more than he was expecting.

“I started shaking,” he says. “Absolute shock.”

He was sent to HM Prison Thameside, a category B facility in southeast London. Yorke survived, he says, by retreating into himself. He was terrified; he mostly avoided other inmates.

But he secured a job in the prison library and made two friends there. One was straight; the other was gay. After the latter left prison, he killed himself, says Yorke. “He overdosed on G.”

It was at the library that Yorke found his escape: documenting in three memoirs his experiences, trying to make sense of them. “Writing got me through it,” he says. It wasn’t just for him. He wanted others to understand the reality of these drugs, this scene, and in particular families stumped by what their loved ones might be lost in.

After 19 months, the authorities offered Yorke a deal: an early release from prison, in exchange for being deported back to New Zealand. He accepted. En route he was able to book a cheap Airbnb room for his first night. His friends were long gone, his family had moved to Australia — all except one.

With the help of a local charity he found a motel to live in, and signed on for unemployment benefit. He had no money; he knew no one. It was worse than being in prison, he says. “At least there you get three meals a day, heating, somewhere you can call your own. Once I landed there I had nothing.”

And so, one day, late last year, not long after arriving, Yorke went to find his father.

“I found that my dad was dying,” he says. The Alzheimer’s had rendered him bedbound, often unresponsive to his surroundings. “I spent almost every day with him. We talked about all the stories of years and years ago. Even while he was asleep — the nurses said to me, ‘Just talk to him, because the last organ to go is the ears.’ And in the end after three hours of sitting there I was talking and said, ‘It’s such a shame that we got off on the wrong foot and that I didn’t come down and tell you [I’m gay] myself; that my sister told you before I had the chance.’”

His father’s response severed everything he thought he knew.

“He opened his eyes and said, ‘That never happened.’”

After more than 20 years, Yorke says, his father told him that his sister had not phoned to tell him Yorke was gay, and that in turn he had never said his son was unwelcome in his house.

“He said, ‘We thought you’d just pissed off because you didn’t want to see us and you haven’t spoken to us for 20 years because you didn’t want to have anything to do with us.’”

Yorke’s facial expression as he recounts this is unlike any other he has displayed; a kind of jarred grimace, as if punched in the jaw.

He has stopped speaking to his sister and is only pleased that he was able to make amends before his father died early this year.

“It has taken me a long time to come to terms with that,” he says. “I had wasted two years of my life [in prison] when I could have been spending it with him.”

That time inside, however, taught him valuable lessons: that “I’m a lot tougher than I thought,” he says, sadly, but also “that I need to be more confident.”

He moved to Cannes this summer and met a new boyfriend, who flits in and out of the room as we speak. “There are four people now that I can trust,” says Yorke. “Out of 3,500 that used to come through my door.”

He rolls another cigarette, inhaling slowly. If he could travel back a few years, before he fell down this well, what would he say to himself?

“God,” he says, before an epically long pause, as if scanning through the horrors. “Remember there’s always a choice.”

There is one more question. What was his father like?

“He was a tough man,” says Yorke. “He never would have given me anything on a plate or helped me out with anything.” He looks down for a moment; his voice drops.

“I’ve known from a very young age I had to forge my own way.”

Some names have been changed.