Dusk, in a sparse restaurant in Harar, eastern Ethiopia. John Hurt is sitting across the table performing lines to me from The Naked Civil Servant.

His voice – that brandy and gravel baritone, the same one that in 1987 boomed out on AIDS public information adverts on TV warning people not to die from ignorance – reverberates around the restaurant.

It is 2014, nearly 40 years since he played the writer and "stately homo" Quentin Crisp in a role that many advised him against taking. To play an effete homosexual, as the dinosaurs of the English acting establishment would have described Crisp at the time, was, he was told, to bid farewell to one’s career.

But it made his career. It made him. As the words slip from his mouth, now cradled by wrinkles, he conjures the defiance and vulnerability of Crisp so beautifully that my eyes fill. Hurt keeps going. He can see what this means to me. He has seen it a thousand times. Gay men would often approach him in the street to tell him how transformative it was for them to watch Crisp alive in Technicolor, in full, brazen mauve, sashaying down the street, all scarves and rouge, waving at sailors and giving bigots the middle finger.

The fact that most gay men are not fabulously camp was not the point. Hurt brought to life a template for defiance that saved people, including me.

I was 14 when I watched The Naked Civil Servant. It was just before I came out at my comprehensive school in 1991. I sat in my parents’ dank 1980s conservatory, on a wooden stall, watching the cranky old TV set slung in there for when arguments about what should be on in the living room became too much.

But that wasn’t the case that evening. I had sneaked in there to watch the film in secret. There was nothing for a gay boy at that time to reach out for, nothing to reflect back and affirm to you that you were OK – that it is OK, that you will be OK.

There was no internet, very few out celebrities, and equal rights were so laughably pie-in-the-sky it never occurred to anyone that one day we would be able to marry. I thought about suicide a lot. I sat on that wobbly stall and watched Hurt as Crisp tell the prim, dim homophobes of middle England to get fucked with such glorious pizazz that I knew somehow I could live. He showed how it could be done; he inverted shame to embody pride. Hurt did not know then that he gave me – and who knows how many others? – a future.

Even when I told him in that restaurant in Ethiopia it did not seem to register – as if by accepting the power of his abilities it would make him complacent, or worse: less human.

With Hurt's death at the age of 77 after being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, we have lost a spectacular talent. We have a lost a man so filled with empathy he could fill himself with the most marginalised; the most despised. There were few more despised people in 1970s Britain than a feminine gay man. And there were few more ostracised people in Victorian England than the next great role that defined him: The Elephant Man.

Hurt captured John Merrick – projecting what it means to be hunted, hated, and feared – so viscerally that his reputation as one of the greats was cemented. He won a BAFTA for it, and was nominated for an Oscar.

There were so many astonishing performances that people remember Hurt for – Midnight Express, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Alien, Indiana Jones, the Harry Potter films – but his performances as Crisp and Merrick rise above the rest.

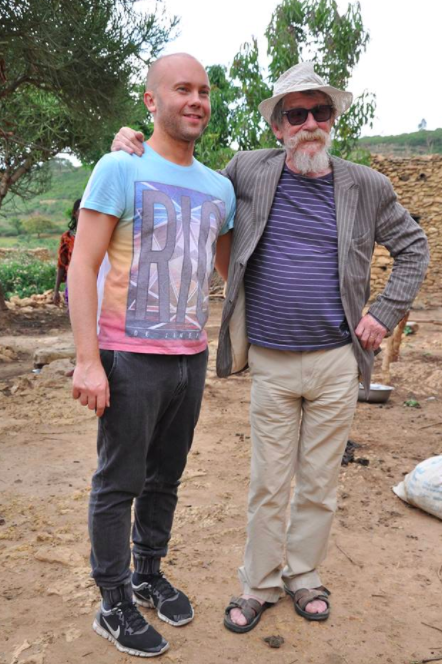

To convey both the courage and vulnerabilities of outcasts takes an extraordinary person. During the week I spent with Hurt in Ethiopia I saw the extraordinary in him all day, every day. We were there because he was patron of a charity called Project Harar, which sends doctors and surgeons to Ethiopia to perform surgery on children with severe facial disfigurements.

The head of the charity, who never forgot Hurt in The Elephant Man, approached him to become a patron, not thinking for a moment he would accept. Hurt agreed immediately.

I was sent by a newspaper to shadow Hurt and report on what we saw at the charity’s hospital in Addis Ababa, as well as at the convalescence clinic in the nearby countryside. We met in the airport lounge and discussed what we were about to witness: children whose faces were half bitten off by wild animals; children whose cheeks were overwhelmed by tumours the size of oranges. We both worried about how we might react.

What neither of us were expecting was what the true horror would be. Hurt, his beloved wife Anwen, and I were taken round the hospital to meet the children. Some had holes in their cheeks, destroyed by a flesh-eating infection called noma, through which they had to push their food in order to eat. Some were simply tiny, growth stunted by malnutrition not because they did not have access to food but because their disfigurements were so extreme that they physically could not eat properly. The smell from facial infections, in some of the cubicles, was almost overwhelming.

But it wasn't any of this that hit John, Anwen, and me like a boxer’s punch. Watching Hurt meet those children, and how he interacted with them, revealed precisely what it was that knocked him back: their loneliness.

Many of these children had been cast out, some sent out into the wilderness to look after animals because they were believed to be possessed. Others were kept inside, away from all other children, to prevent them being hounded by the other villagers. They were not used to human touch.

To see Hurt reach out and clasp their hands, to see their faces react with caution, bafflement, and then deep relief – the medicine of human touch – was to know that he was a great actor because his empathy ran so deep.

He did not talk much. In the entire week he did not show any signs of ego, narcissism, or histrionics – precisely what one might expect of a movie star – because he was too busy connecting with others. He watched those children with kindness. He sat and played with them. He laughed with them.

“When you meet them, because of their energy, of their personality, it’s not just an image of horror, it’s a whole person,” he said. “What is staggering is that they cope. That is profoundly moving. They are rejected and they still go on.” This, if anything, encapsulates the spirit of Hurt and his many courageous characters.

When I eventually managed to steal him away for an interview he spoke of his life and his career. He talked about how profoundly he loved his wife, how he had finally found the right woman after several failed relationships. He told me why he chose the roles that defined him.

“My career is tied up with victims, with people the public don’t normally see, with people who were victimised," he said. "Quentin Crisp was a classic example, and the Elephant Man, certainly. Even Max in Midnight Express. They were all on that side of life. A scapegoat. There’s a link there with me. A lot of my youth was lonely."

As we talked more about his childhood he said, plainly, "I was abused at boarding school. I took it as a token of love. Someone was at least being affectionate.”

He told me he didn’t know that there was anything wrong with being abused at the time. “I jut thought that was what schools did, how they were. If I’d mentioned anything at school I’d have been pooh-poohed as if I was being rather fanciful. Abuse wasn’t a word anybody used.”

There were two things, Hurt said, that helped him realise what had been done to him was wrong.

“Because of women’s liberation and gay liberation, battering on your door from decade to decade, you think, Hang on, let me have another look at things, and you lift up stones and think, I suppose that wasn’t a good idea really.” Hurt was nothing if not understated – in person, at least. He was an introvert.

After years of being a wild child of British acting, boozing it up with Oliver Reed in the '70s and '80s, he told me, he had given up drinking in 2009 when he met Anwen.

“I only drink red wine now,” he said with a devilish smirk. But he knew it was a problem. “I drank for fun originally and then you get tied up with alcohol. It catches up. Hopefully you recognise what’s happening.” He said the drinking ruined his marriages, but the idea of going to Alcoholics Anonymous appalled him. “How dreary can that be!”

There was something else he said: that he was surprised and amazed he was still alive, that he had lived this long after so many decades of woeful disregard for his own health.

Thousands of miles away in London, the following year, Project Haraar asked Hurt if he would appear on stage at a ticketed event An Evening With John Hurt, to raise money for the charity. He asked if I would host it. Beforehand, in the bar next to the theatre, fans came up. He signed their books; he chatted with them sweetly and quietly.

Once we walked on stage to a sold-out theatre, the lights blinding us, he seemed to relax. As the evening unfolded and he recalled his life and work, his roles, his Quentin Crisp, his John Merrick, the audience – young, old, gay, straight – feasted on every word; silence interrupted only by warm laughter and loud applause. They gave him a standing ovation. Backstage I hugged him and said goodbye to the man who saved me.

John Hurt – or Sir John Hurt as he became in 2015 – was the quintessence of humanity. The lonely, the ostracised, and the rejected will always love him for helping them – us – stay alive. And for reminding the world that each and every life, from Oscar-nominated actor to outcast, is precious.