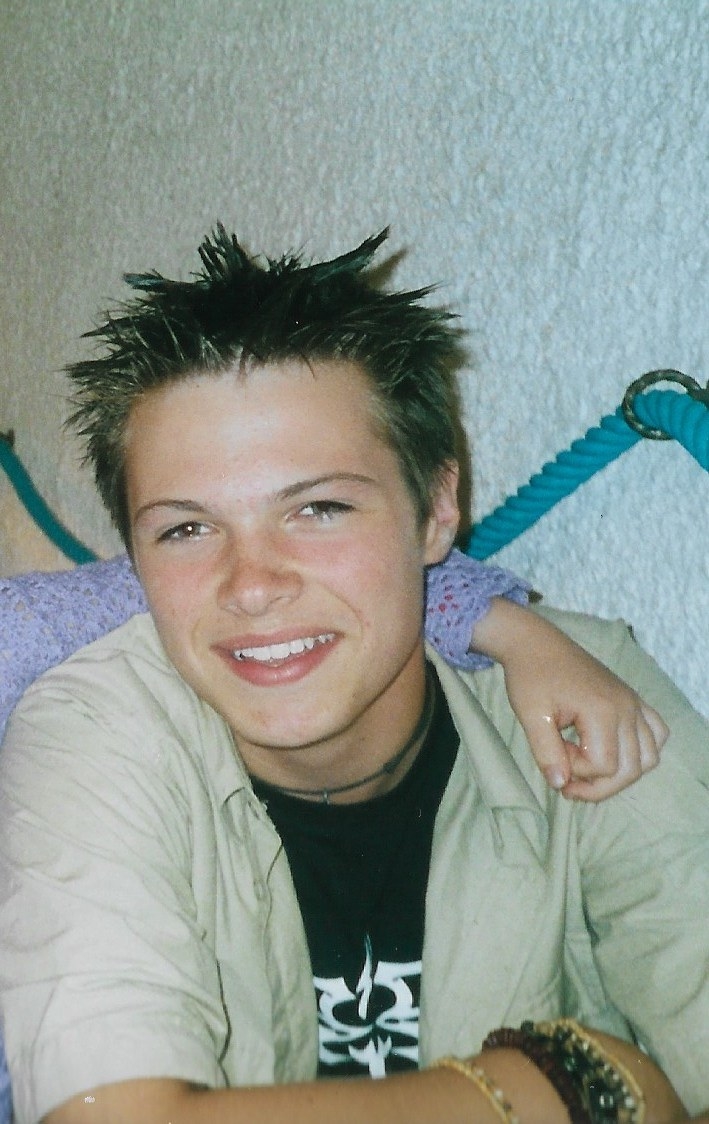

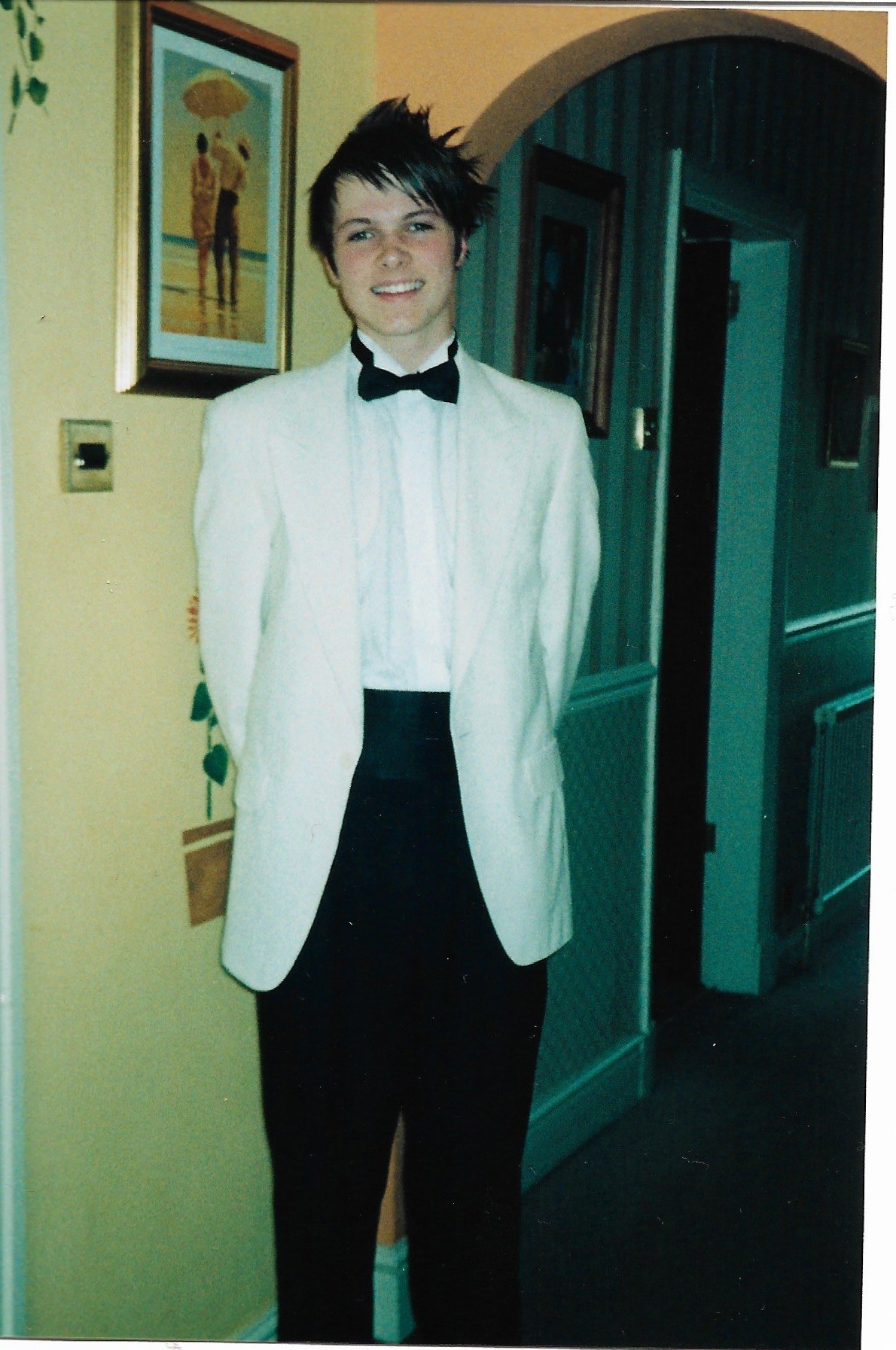

A 16-year-old boy is sitting on a park bench in Stockport, Greater Manchester, waiting for an important delivery: the cream tuxedo he has ordered from a nearby suit hire shop to wear to his school prom.

His name is Nathaniel Hall. He has neat, even features, light brown hair teased into spikes, and beads round his neck. No one knows he is gay — he cannot say the words — but wearing a dinner jacket that colour is his way of at least saying something: that he’s different.

He has no idea how much more different from his classmates he is about to become.

A few minutes later, a man in his mid-twenties called Sam will look over, catching Nathaniel’s eye before striking up a conversation, sparking in the teenager a mounting excitement that, with college imminent, there might be a chance he can at last explore being gay — and maybe meet someone like him.

Nathaniel does not know that theirs will be a short fling with lifelong consequences; that the first time he has sex he will contract a virus that will fill his life with silence.

Fifteen years later, he sits in his flat in Levenshulme, south Manchester, a few miles from the park bench, telling BuzzFeed News what unfolded from that day: the HIV diagnosis, how the shock muzzled him, preventing him from telling his parents, and how that corroded everything that followed.

The silence will end soon — for Nathaniel at least. Three weeks from now, just in time for National HIV Testing Week and World AIDS Day, he will stand on stage to perform the play he has written about what happened to him, a middle-class boy from the suburbs who became HIV-positive on his first time.

He is, to put it another way, about to leave the second closet that formed around him when he had not even escaped the first.

“It’s terrifying,” he says, now aged 32, “and exciting. It’s changed who I am.”

But in writing the play, and revisiting the teenage boy he was, Nathaniel Hall has stumbled upon something beyond the silence of HIV, something that spreads even further: the isolation that still engulfs LGBT teenagers, and how that leads to danger.

Sam looked to Hall like a mythical creature in Stockport that afternoon in 2003: a real gay man, hair flecked with peroxide, T-shirt tight enough to leave little doubt, tanned so deeply as to summon the exotic.

Hall, who had never seen someone so obviously, definitely like him before, was entranced. Sam glanced over a few times.

“It was the summer I was leaving school, with that sense of becoming an adult and starting to find my way in the world,” he says, smiling under his thin-wired glasses and angular, cropped haircut. “I was ready to go out there and be gay and find out what that meant.”

Until then, all it had meant was being called names in school: faggot and poof, mostly. He remembers being kicked in the back so hard he was smashed into a vending machine.

The only mention of homosexuality came during sex education: a video about a gay man dying of AIDS. There was no advice about how to ask a man to use a condom, or what to do when he says you will be fine without. It all seemed so remote.

“I came from white, middle-class suburbia,” he says. “‘People like you don’t get it.’ That was the overriding attitude in the back of my head.”

So when Sam ambled over and sat with Hall on that bench, only the heady prospect of connection loomed. They started talking. “He looked like Will Young. Seeing someone openly gay was wild.” To this day he cannot remember if Sam was 23 or 26, only that he seemed like an adult. “It didn’t feel menacing or predatory at the time,” he says. Now he is not sure.

They arranged to meet again. After a few times they went back to Sam’s flat, where exploration progressed further: Clothes came off, a safer sex pack appeared. But Sam put the condoms to one side, removing only the lubricant from the cardboard wallet. “I’ve been tested, it’s alright,” he told Hall. “We don’t need to use those.”

It did not occur to Hall to question this. “I knew nothing,” he says. All he did know was that this older, experienced man was his gateway to the future.

“He had showed me the gay world. We went down to Canal Street [Manchester’s Gay Village]. He was opening the door to that life, so at that point when the condoms were left out it was like, ‘Well, you’re showing me how to have sex, so I’m going to take your lead on that.’”

It happened a few more times that summer. Hall’s mother suspected something, and asked if he was gay, prompting him to tell her about Sam. She said he was too old and that Hall should end it. Sensing she was right, he did.

But just before starting college, Hall fell ill on a family holiday in Menorca: vomiting, diarrhoea, a fever. A doctor, when examining him on his return, thought it was a waterborne virus.

Only weeks later when he had discharge from his penis did Hall think to go to a sexual health clinic. By then he was quietly building a relationship with a boy at his new sixth-form college.

At the clinic they found gonorrhoea, but he refused to have an HIV test initially — scared, in denial, rejecting the creeping dread he felt. It would be another few weeks before the staff at the clinic persuaded him, and a further fortnight for the results to return.

“The clinic had this really long corridor and they took me all the way down to the counselling room at the end. They said it straight away: ‘We got your test results back and you’re HIV-positive.’”

Shock set in. “I don’t think I said anything. I remember crying. It felt like being hit by a bus.”

The health adviser at the clinic told him, based on the evidence available at the time, that he could expect to live for another 36 years, taking him to age 52. Although a huge increase from the two-to-five-year death warrant issued to people diagnosed in the 1980s, this was still a limit, and much less than the near-normal life expectancy those diagnosed today can expect.

The staff kept him there for hours, long after the clinic closed for the day, seemingly aware how young and vulnerable he was.

“I knew only that it was untreatable and that I was infectious,” he says, “so another layer of shame and self-hatred was added to the stuff I already had as a gay man.” The clinic encouraged him to telephone a friend to come and look after him, but even she could not help with the most important decision.

“I was terrified,” he says. “I knew I had to go home and tell my family, but I had already had that conversation with my mum about using condoms and it was too late: I’d already ballsed it up. The horror of feeling I had to tell them means that even now I can feel the anxiety — that comes back — of having to say, ‘I’m human and I’ve made a mistake.’”

As Hall put the key in the door to his family home he knew there were two options. “I could have walked straight into the kitchen and just said it, or I could go upstairs into my bedroom and shut the door.”

He did the latter. He didn’t tell them for 14 years.

Instead, he phoned the boy he had been secretly kissing at college, who, unfazed by the news, ran the several miles between their houses that evening to see him; to tell him it made no difference, that they could still carry on. They stayed together for the next eight years.

But Hall went through college without his family knowing. He was able to tell his personal tutor, who suggested informing the principal because he had a sister who’d been a nurse for AIDS patients in the 1980s.

The principal would invite Hall to have lunch in his office. “We used to sit and talk, and he would offer advice, always with the best intentions, but not always the best advice because it was coming from stories he’d heard from the AIDS ward.”

The difference in the impact of HIV in the early noughties compared to the 1980s was vast: The introduction of effective antiretroviral medication in 1996 transformed lives and prevented HIV from being an automatic death sentence. The general population was scarcely aware of this, however, ensuring stigma remained.

Hall only told a few select friends. He went through university and the rest of his twenties without telling his family: through being constantly exhausted while studying for his degree because the virus had been left untreated; through then being put on antiretroviral medication that would wake him in the night with heart-pounding anxiety; and through the depression that arose later on, when the accumulative effects of being alienated from those around him while managing the condition hit.

Or, as Hall puts it simply, “living with this trauma and not talking about it. I always remember that feeling of isolation from people.” So, for example, when he saw Sam in the HIV clinic one day, years later, and Sam avoided him, Hall could not tell his family about it — the choking resonance of it all.

Instead, it would take a “bit of a breakdown” aged 30 to force Hall’s hand.

“I was partying too much, drinking too much, taking drugs in the middle of the day, getting really angry at things that shouldn’t make me angry. I put my hand through a plate-glass window.” It escalated to a stage where, he says, “I looked in the mirror and didn’t recognise who I was anymore.”

Hall knew that what he had to do was write about his experience; to exorcise it by retelling it as drama. He had already been accessing support from a local HIV charity, the George House Trust, and had begun giving talks about his life. But dramatising and performing it would also mean having to tell his parents, along with everyone else. After several failed attempts, this was the only way.

“The longer I left it, the more it felt like they’re going to be upset that I kept it from them,” he says. “Would my mum think she was a bad mother because her son can’t talk about this with her? I blamed myself too much for what I’d done — that I had failed, that towering shame and stigma I was putting on myself, when actually it’s just a virus and I was really, really unlucky. All these things were racing through my head. It’s exactly like the things that go through your head before you come out: the fear of doing it is worse than the act itself.”

He wanted to tell his older brothers and younger sister, too. So, a year ago he wrote his parents a letter. “Dear Mum and Dad,” it began. “There’s something I need to say and I’ve needed to say for a long time. I’m HIV-positive.” Two days later, he received texts back saying they loved him. His mother then arrived at his flat with a houseplant. He shrieks with laughter at the memory.

“I said, ‘Why have you got a houseplant?’ She said, ‘I don’t know. What do you bring when your son tells you that?’” They sat talking. “I don’t feel hurt or upset you’ve not told me,” his mother said. “I’m just upset that you’ve gone through that.” Recounting this, Hall begins to cry.

He says his father, after reading the letter, thought he would lose him, unaware of how much things had changed since the 1980s. They are still acclimatising to talking about his condition, says Hall, but something on the horizon is about to provoke more conversation: the play.

He has been working in theatre, with young people, for years. And it was an experience with a group of 15-to-25-year-olds last year, in which they worked together on a theatre project about sex and relationships, that finally persuaded him to commit his story to performance.

“They were so bold, they made this really beautiful show,” he says, “taking their personal stories and traumas — that made me want to create the show.”

He started using short pieces he had already written as a basis for the play: a letter to his 16-year-old self, the letter to his family. He also knew that he had to perform the one-man show himself. “Because it’s me standing up on stage and going, ‘This is me, I’m HIV-positive.’”

There are, he says, many people in London who speak out about HIV but fewer up north. He hopes someone will see it and live more openly.

As he talks — self-assured, observant — he seems far removed from that naïve boy sitting on the bench. He has a stable boyfriend now, along with a career and, soon, a voice. But the writing of the play has taken him back to who he was then, with an adult awareness of what happened with Sam. It has unleashed a series of realisations.

“The idea that that first time wasn’t romantic,” he says. “The idea that it might not have been the way I saw it at 16.” He does not know what to make of Sam. Was he predatory? Did he know he had HIV? It seems Hall does not want to judge him too harshly, not least because that would be more painful. He remembers a time in his flat with two friends of Sam’s, of smoking cannabis and then the memory cutting out.

One day, immersed in memories, Hall wrote everything down suddenly. “It all came out. I read it and thought, ‘Where’s that come from?’” He workshopped it with colleagues and a performance artist friend, and the eventual result was his play. It's called First Time.

“The first few scenes of the play are of a younger me,” he says. Although this poses a problem in the performance of revisiting innocence long eroded, it has also been eye-opening.

“It’s really clear to me that he’s a child, that he’s not grown up,” Hall says of the teenager he was.

Something strange happened during this process. Where before, when Hall had written the letter to himself at 16 telling himself he was going to be OK, now, by revisiting that age, it was as if a message was being sent the other way: “The 16-year-old me said, ‘I’m sorry. I’m sorry I fucked it up and that what you’re going through now is because of what I did.’”

The effect was transformative. “Everything shifted in my head because I thought, ‘Actually, yes, I do need to forgive myself.’” In doing so, he realised that his entire adult life had been spent pressurising himself with perfectionist demands, as if to rectify his own imperfect mistake.

“That’s within the play,” he says, “this idea of fucking up and then not having to be perfect to make up for it.”

The instinct to pressurise oneself in this way is, he says, remarkably common among gay men, regardless of their HIV status, because of how the overall message from the world remains: You are different; you are not good enough.

The effects of this for Hall have been both perfectionism and an inability to assert himself in sex and relationships — a reaction shared by many gay men bullied in their youth. “It’s made me realise that I sometimes allow things to happen to me when I don’t want them to be happening to me,” he says, “and I don’t say anything.”

For others, he sees this low self-worth, and the accompanying isolation, spilling out into other areas.

“It’s painful and hard to go through and sadly for a lot of people that I know they don’t make it through it,” he says. “They commit suicide or they overdo it on drugs and we lose them. And then that’s portrayed in a certain way, of leading a ‘hedonistic lifestyle’, but people don’t realise the pain that’s underneath that.”

Only this week has some hope of this changing emerged. The Scottish government — the first in the world to do so — announced it would introduce mandatory lessons on LGBTI issues, in an attempt to reduce homophobic, biphobic, and transphobic bullying, and the resulting slide into mental ill health and self-destruction. For many, the need has never been greater: Where Hall sat on a bench and met someone, teenagers today have phone apps and social media, escalating opportunities both for connection and for risk.

The proportion of young people contracting HIV has not shifted, either, in the 15 years since Hall was diagnosed. Just over 1,000 people in Britain under the age of 24 were told in 2003 they were HIV-positive, compared to over 9,000 overall. In 2017, despite all the attempts to educate young people and equip them with prevention methods, over 500 were still diagnosed, out of over 4300 in total. While the trend for transmissions overall is reducing, the percentage of young people being diagnosed persists.

All of which informs Hall’s decision not only to write the play but also to include more about the unuttered complications of being a gay man today than he originally intended.

“I’ve got to do this,” he says, to “break through the shame”. It will mean, however, facing up to the entirety of his past, and specifically “having Mum and Dad sit in that audience and see me with white powder across my face and see me talking about going to the sauna and all those things. It’s a cleansing ritual in a sense.”

But unknowingly, as Hall talks about the play in which he will finally enact his past, he reveals how much remains of that 16-year-old who thought his feelings mattered less than others, who blamed himself and suffered. When asked about the prospect of re-experiencing those times on stage in front of his parents, it isn’t his own pain he invokes.

“It will be hard,” he says, “for them.”

Some names have been changed.

First Time will be performed at the Waterside Theatre, Sale, Manchester, from Nov. 29 to Dec. 1.