BuzzFeed News has reporters across five continents bringing you trustworthy stories about the impact of the coronavirus. To help keep this news free, become a member and sign up for our newsletter, Outbreak Today.

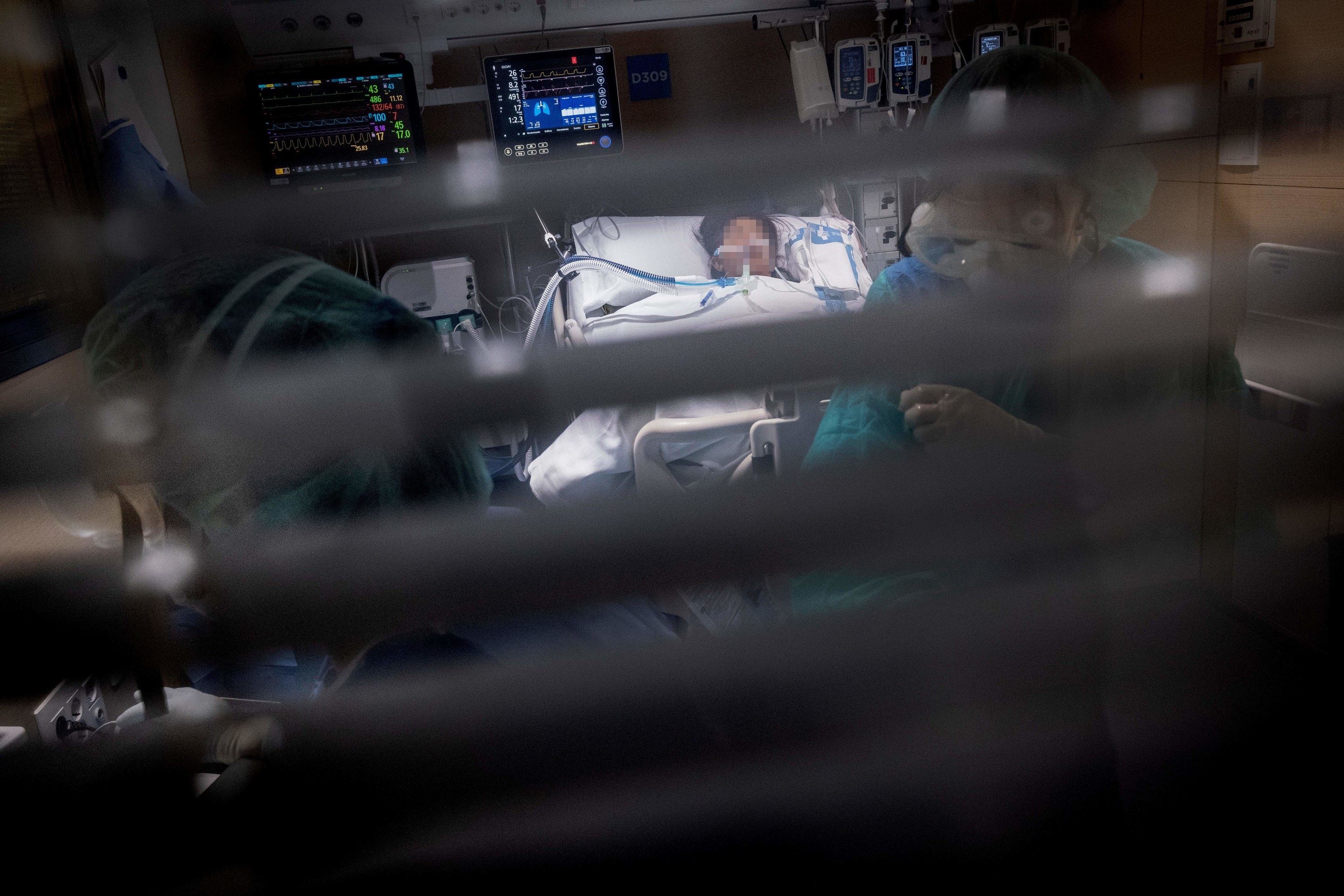

The image of separation in the final moments is among the cruellest of the pandemic. Families are kept away — stuck outside an intensive care unit or told to stay at home and await news, unable to be with their loved one at the very end. What this means for the coronavirus patient can cause the most distress.

But now, with daily deaths still in their hundreds, a student doctor on the front line of the COVID-19 pandemic has decided to speak out about what happens in the patients’ final days and hours — in an attempt to comfort those left behind. First he contacted BuzzFeed News by email. “Can you help me send a message to these loved ones?” he asked.

“They are not dying alone,” he said. “We are there with them, holding their hands, telling them about what is happening outside, talking to them, and reassuring them even when we aren't sure they're awake. It is breaking my heart that people think their loved ones do not have people who care for them with them in their last moments.”

He did not want to be named — to prevent his own family finding out what he has experienced, and because he wanted the focus to be on those we lose and those bereft. We will call him Luke.

The following night, after another shift in one of the three intensive care departments at St. George’s Hospital, south London, Luke spoke on Skype for hours. He described what the ICU is really like during this crisis for those being cared for, the messages passed between families and patients through staff, and the humanity that fills the units.

Weaved through this is, however, are details about what the clinicians are facing — and what they have to do to cope.

Luke began with the overriding approach taken towards coronavirus patients in ICU. In contrast to the cold isolation many fear, “Your loved ones are being cared for as much as they can by people who genuinely love them,” he said — it might not be the kind felt by a husband or a mother, but in the dedication and personal attention it is a love all the same; administered by those who are “there because they want to be”. He began to describe what that looks like.

First, with how staff connect with patients: the talking, day or night. Many are on ventilators, unconscious and sedated; some may not be aware what is happening. Others, like Boris Johnson in intensive care last month, are receiving oxygen and fully awake. Often patients will go between the two, sometimes waking up to see the machines and tubes.

This can be scary for patients but, “We’re there and we calm them down,” he said. “We talk to them and explain things. We say, ‘It’s OK, don’t worry. [The ventilator] is helping you breathe.’”

The staff try to normalise the situation. “When someone’s quite lucid we’re explaining things as we do them, like, ‘Don’t worry, just going to have to wash your bum! We’re narrating it so that they know what’s going on.’”

The intention is for the patient to know there’s someone there. “It will be four in the morning and one of the nurses is just sat with her patient, stroking their hair or holding their hand,” he said. “Just talking to them, saying, ‘Oh, you’re not missing much outside. Don’t worry, everyone’s in lockdown so even though it’s sunny, nobody can enjoy it.’ Anything to explain what’s going on outside.”

It can involve offering praise or encouragement when a patient is regaining consciousness or showing signs of improvement, but not yet able to speak. On one occasion, Luke was buoyed by a patient’s condition and started saying, “Great work, you’re doing fantastic!” Shortly after, “I was told, ‘Actually that person’s a very established, very esteemed surgeon, so he definitely knows what’s going on.’”

Luke laughed a little at this, still embarrassed, but said the attempt to form a connection and to console with lightheartedness is common. “And if you make a joke and someone chuckles because it’s a terrible pun you know they’re with you a bit. We do that sometimes just to see how people are feeling.”

Other times, the staff can’t tell whether someone can hear them.

“We talk to them without any knowledge of whether they know what’s going on,” he said. For someone like him, only three years into witnessing how the ICU staff work, “it’s amazing to see the doctors and nurses engaging with these patients and to see how much they care. We’ve had some very young patients and so they talk to them like their own kids. They’re explaining things like, ‘Oh I know that’s horrible right now, don’t worry, we'll clean that muck out of your lungs.’”

Nurses and healthcare assistants comb their hair, too. “You’ll be saying, ‘Oh, you look lovely.’ Or, ‘You might have to have a hair dye after this but don’t worry everyone outside is struggling to get a hair dye too.’”

Often, before being intubated and sedated, patients are asked if there is anything they want to say while they still can. “It’s mainly, ‘Just let my wife know….’” he said before stopping himself. Only later in the conversation did he reveal that he has still not allowed himself to cry.

“The majority [of patients] have already had to have these discussions while they were in the ward so by the time you’re in the ICU most things have been said. They’ve spoken to family, and family aren’t allowed in anymore. The closest is the corridor or outside the department and even then we’ve asked people not to come in because we’ve got so many people coming in all the time. But we do make a point to ask [patients if there’s anything they want to say]. It’s mainly reassurance: A lot of our patients just want us to reassure their family.”

This can be regardless of how they feel themselves, however. Most patients are worried and simply want to be able to breathe properly again, he said. Once attached to oxygen or a ventilator, staff will still convey messages from loved ones. Sometimes family members will call all through the night.

“We do pass things on if we can,” said Luke. “We tell the patient whether they’re awake or not, when we’re changing them, when we’re putting in a drip or sorting out the ventilator.” He adopts the cheery, everyday tone he uses: “‘Oh, your wife called, she is worrying about you. You’re going to have to really get better soon.’”

The calls from family members can be practical, to help staff provide the most effective care: telling them their father or wife hates needles, for example, so nurses can keep that in mind when taking blood.

But it can involve delivering the most important message of all: that they love them. That always gets passed on, he said. “Any time that we have anybody call, we reiterate [to the patient], ‘We’ve had another call from your partner or your kids. They’re missing you. Hopefully they’ll see you soon so you’re going to have to hold tight.’”

Messages can travel the other way, too. If a patient’s condition is looking more hopeful, a member of staff will often let them know they’re going to tell their wife or son that they’ve come round.

Even the tiniest forward steps in treatment make all the difference to staff, he said — “when someone can squeeze your hand, when someone can respond to you”. And if a COVID-19 patient’s condition improves markedly, it uplifts the whole department.

“It’s the most insane kind of feeling for everyone in the ward,” said Luke. “It’s news the whole night – the whole week — that this patient might be able to leave. It’s something to cherish.”

He remembers one patient in particular who was being prepared for discharge. “The whole ward was on fire. It was palpable excitement. Every time their stats went up to a higher level and we could bring the oxygen down everyone was like, ‘It’s going to happen!’” He made a note of what the first person said when they made it out of ICU. “They were able to mouth it,” he said: “Thank you.”

But the reason for such excitement, at that point in late April, was simple. “We didn’t have a single person leave for weeks.”

The proportion of patients improving and leaving ICU is increasing now, he said. But every day, death remains the reality. Luke, like all the staff, will come into work after having cared for a patient for many days, sometimes weeks, and be told the news by a colleague: “They didn’t manage.”

The unpredictable trajectory of COVID-19 means sometimes this can happen quite quickly, even after showing signs of recovery — but either way, they do everything possible. “For the majority of people we keep going even though the signs are hinting that they’re not doing well, because people can pull through,” he said.

Without intending to talk about the effect of all of this on clinicians, Luke began to depict what life for him and his colleagues has been like since March. He spoke of the physical demands in the ICU, particularly for nurses, healthcare assistants, and junior members of staff.

“The shifts are hard,” he said, “You have to wear this [hazmat] suit, you’re hot, you’re trying to hold someone or move something.” They wear hazmat suits, he explained, because they ran out of surgical gowns. Some COVID-19 patients are on kidney dialysis and need bedding to be changed regularly. “So you’re desperately changing all the bedsheets but at the same time your gloves are so soaked in sweat that they're falling off and you’re trying to keep your visor on.”

Nurses in particular bear the brunt, physically, he said, with hours at a time in masks, goggles, double gloves, and visors, “drenched in sweat” doing the “very best they can” and trying to help each other. Their sheer practical skill has left him astonished. Early on, while attempting to wash and turn a patient while ensuring the lines and tubes didn’t become detached, a very experienced nurse intervened.

“She just grabbed something from me and did the most amazing manoeuvre of washing and holding the patient up and was like, ‘You need to hold this and you need to push as hard as you can!’” Luke obeyed as quickly as he could as the nurse turned to him again. “She said, ‘You need to realise this is wartime nursing now.’”

The image stuck with him, ringing out over the following weeks as the peak of cases and deaths hit the unit in the middle of April.

“Watching everything that we’ve seen is very much like a war,” said Luke. “You don't know if your colleagues are going to drop, you don’t know if you are going to drop, and you don't know if actually the PPE is effective enough because nobody knows. So everyone has this baseline anxiety. A lot of the very senior doctors and nurses have been like, ‘I guess we’ve all got COVID’ because we really have no clue.”

Staff were not being tested, he said. They simply had to go home if symptoms developed. Then they started dropping “like flies” as they contracted the virus. Some ended up in the very unit that they had been working in — cared for by their colleagues. Many did not fit the demographics of many COVID-19 patients.

“We've had more people in the ICU who didn't previously have health conditions, who were young,” said Luke, “whether they be our staff or staff from other hospitals. That’s tough for a lot of our staff, to see that,” he said. “One of the cardiac nurses did die. It hits everyone like a brick.”

Support between colleagues has been incredible, he said, but “that’s not to say people aren’t scared because people really, really were. A lot of colleagues had quite dark conversations about ‘if and when I get sick I want x, y, and z treatment.’”

When the biggest wave of patient deaths struck just before Easter, the ICUs at the hospital were so overwhelmed there weren't even enough nearby rooms to talk with families and loved ones. “They had to put up makeshift kind of blockades in the corridors,” he said, in order “to have these private discussions. So there were a lot of discussions behind showcase stands, which had makeshift cubicles set up. We’ve managed to get more adequate bays now. But I remember one time it was pretty uncomfortable because students are taking food through but there’s a very significant discussion of ‘they’re not going to make it’ being had and it couldn’t be had anywhere else.”

It wasn’t that the discussions were not being conducted with the highest of sensitivities, he said, but rather that the basic practicalities were strained to the limits. And in the first few weeks, the rapid repurposing of theatres and rooms to accommodate the explosion of coronavirus patients meant the hospital even looked unrecognisable. “You’ve got handwritten signs pointing towards bits [of the hospital] saying, ‘COVID DON’T ENTER’,” he said. “It’s been surreal and now it’s hitting people more because [then] people were in survival mode.”

Exhaustion comes in waves. Staff are “trying to nap on chairs, but there’s nowhere to sleep,” he said. And when they try to take a break, ‘You’ve got staff-rooms full of people where people are trying to socially distance.” It’s almost impossible, he said.

Many are hungry, unable to grab a break or find food. In the first few weeks, in particular, panic-buying meant supermarkets were impossible to use, with empty shelves awaiting nurses and doctors — if they were even open in the hours that ICU staff needed to shop. In the middle of a night shift, in the comparative quiet, the physical and mental stresses swarm junior staff like him. Luke describes a typical thought process: “Am I shaking because I haven’t eaten or because I don’t know what’s going on because I’m so exhausted?’” Care packages for staff now get delivered, which helps, he said.

The strange collision of humanity, sterility, and disease remains. “You're in an environment which is really not very human but it's also perfectly human and the most human you can have,” he said. “Everyone’s dressed like an alien and you’ve got bleeping and weird lights and crash trolleys around but then you’ve also got people being the most that they can be.” It is this — people rising to the highest level of professionalism and compassion — that helps sustain him. “It grabs you,” he said, “and drags you back to the present.”

At the end of a shift, “You come home and there’s no one around. You can’t go anywhere to disengage with it all. If you talk to anyone, it’s only to talk about COVID and the only people you can talk to you are your colleagues and they don’t want to talk about things.”

Domestic isolation is common because so many clinicians opted to not stay at home but to stay in an Air B’n’B, he said. “I live alone because all of my housemates have left. A lot of clinicians had to leave their families and are very worried about spouses or children or parents.”

Online mutual support groups, helpline, and crisis lines have been set up for NHS workers, said Luke, but the psychological fallout is now crashing ashore. A clinician friend phoned to ask for help. “She said, ‘I don’t know what to do, I’ve been crying every night and I have no clue how to approach this.’”

Senior clinicians have been extremely supportive of the less experienced, guiding the team through, despite their own pressures. “They’re supporting their patients, themselves and their families,” said Luke. “You have no idea the kind of inspiration they are to everyone — and everyone can see it. That’s what’s in the ICU. It’s not what you see in the movies where it’s just cold, grey, bleeping. There’s something else: these insanely inspiring people who are there to do everything they can and they will put themselves through hell and back to do anything they can — to be there for their patients. I’ll never forget that.”

One of the problems, he said, was how quickly everything happened, that there was no time to properly prepare nor manage the crisis when it struck. When asked if he has allowed himself to cry yet, Luke replied: “Very much not. A lot of people have, on the shifts, in the break rooms. But actually a lot of the time it feels more numb.”

Instead, anger surfaces in small, isolated ways. “Someone throwing their PPE off,” he said, “which is absolutely not what you’re supposed to do. It’s because they’re so angry at what’s going on and the fact they can’t do anything. People being frustrated at the futility of a lot of it.”

Questions are hardening about the lack of testing, the PPE, staffing levels, and the actions or inaction of the government, he said. Overall, “Only now people are starting to realise what it’s doing to them.”

But Luke doesn’t want the public to think of clinicians as angels or superhuman. Tensions have erupted into arguments, he said, sometimes over mundane matters like food packages being given to one department before another, or an email spat between doctors about what the future holds for their workers.

But mostly because each Thursday at 8pm there is the clapping: millions across the country standing outside or by windows, banging saucepans, drums, cutlery, hooting car horns, in praise at the NHS workers. Luke likes it, but not everyone does. He captures the concern among some colleagues: “Doctors and nurses being called heroes means that when they die it’s a sacrifice of war rather than something that could have been prevented.”

There is now an unspoken sense among staff that the worst could be over, he said, in terms of the numbers of critically ill and dying patients at any one time — but are afraid to admit it in case they’re wrong. And many are not expecting a return to normality this year.

“A lot of us are still in quite high anxiety states,” he said. “We’re all pretty sure there’s going to be another wave as soon as lockdown finishes — so nobody wants to let themselves relax.”

What is certain, said Luke, is that next time everyone will be more prepared.

Until then, he hopes only to reassure families. “It’s horrific to think that people are continuing on with their lives with the belief that their loved ones ended theirs with them not there,” he said. “That’s not the case.” He invokes again the way they talk to patients, telling them about their partners, children, and parents, and the messages of love — bringing the outside world in to soothe their last moments.

“It’s not a situation devoid of humanity,” he said. “Your loved ones are not alone.”