That is not sex, he said. The teacher had just shown a series of sex education videos and asked us what we thought. I’d raised my hand and said they were good but did not mention gay sex. I was 11.

That is not sex, he said. It was 1988, the year a new law was enacted that forbade local authorities and teachers from “promoting homosexuality”. Today is exactly 30 years since that law (which was not repealed until 2003) came into effect. It was so vague as to muzzle everyone working in schools from mentioning gay people. It was the height of the AIDS epidemic.

In the confusion and furore surrounding Section 28 (often called Clause 28) of the Local Government Act 1988, teachers – those we entrust to prepare the young for the world – became mute through fear of contravening it. Pupils like me did not know at the time that teachers had been prohibited from talking about homosexuality, because they had been prohibited from talking about homosexuality.

This would be the only almost-amusing irony. We did not know it, but we felt the absence. My generation did not know how many others would feel it too. Or what the silence would do.

At the time there were demonstrations. There were lesbians abseiling into the House of Lords and disrupting a BBC News studio to protest against the law. Ian McKellen, Michael Cashman, Lisa Power, and others founded Stonewall to fight it, now the biggest LGBT rights group in Britain. These were the adults trying to protect children like me. The public war between them and the politicians proposing this clause is clear, concrete, and well documented. The private battles of the children affected is not.

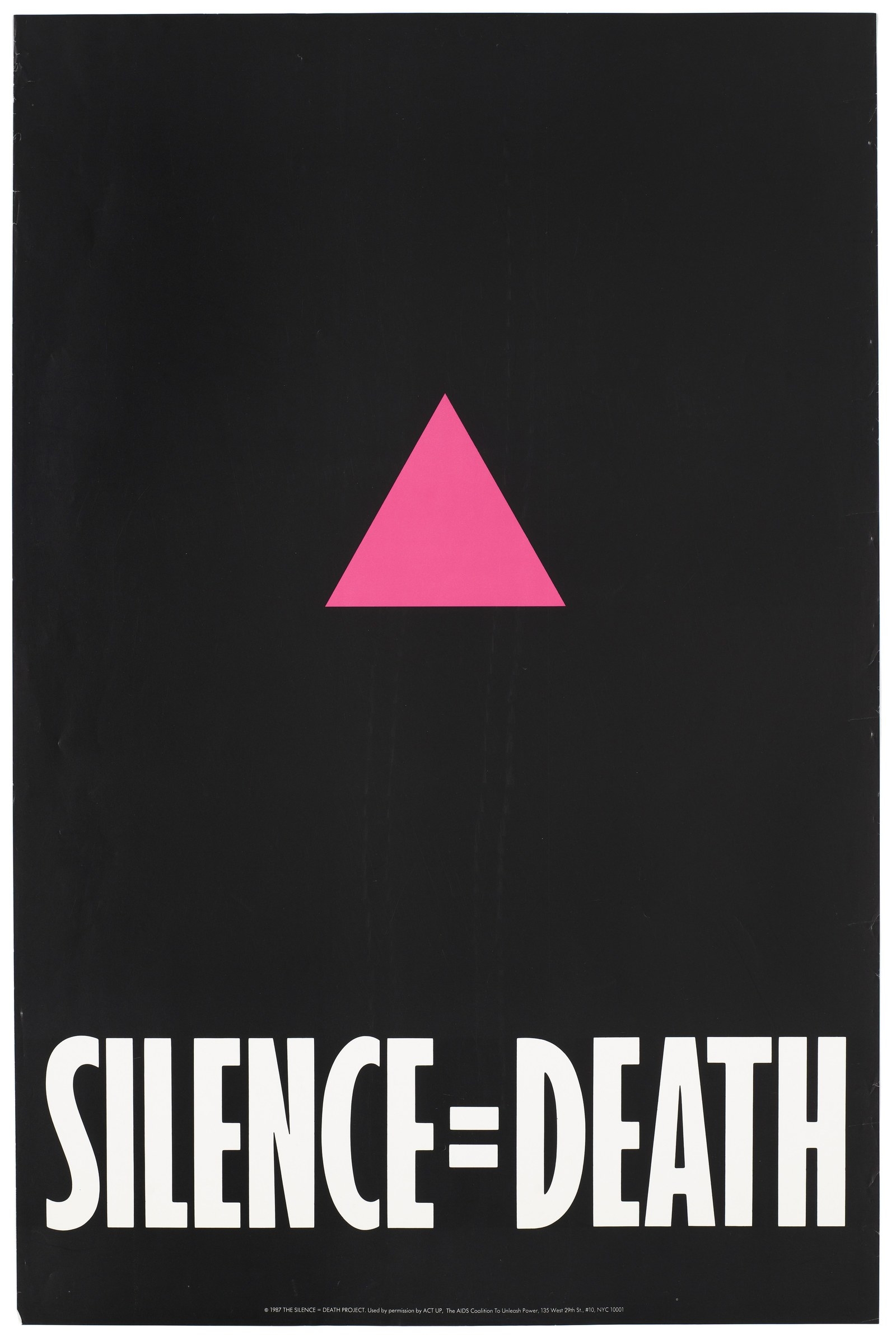

There was also at that time a phrase coined, shouted, and scrawled on T-shirts and placards across Europe and America: Silence = Death. It referred not to Section 28 but to the absence of action to curtail the millions dying from AIDS. But the silence surrounding homosexuality killed many, in ways never fully understood.

In the last 30 years one lesson I learned gradually is that homophobia’s greatest trick is to make gay people do the job for you; that it ensures self-destruction.

But this is just one lesson about homosexuality I wish I had been taught, squeezed in between Tudor history and quadratic equations. The others rippled out over the last three decades in waves. Some were like tsunamis. To convey them now, what I wished I’d learned about being gay, is not to shame those responsible for the silence. History will do that. Instead, this is about the future.

Shall we start with sex? I wish I had been taught something, anything, about gay sex. I am not advocating double maths, double French, followed by double fisting, but is it really too much to ask that someone might inform those who might well later do it that anal sex is greatly improved, or indeed made possible, by the use of lubricant? That it can stop condoms from ripping and, therefore, save a life?

Being taught about the mere mechanics would have helped. I did not even know that two men could have sex in the missionary position. (In 1988 it was illegal to have gay sex until you were 21, five years older than for straight people.) Decades later I would interview a man who did not know that two men could hug and hold each other: All he had been taught was from hearsay, that faggots just fuck in alleyways.

Knowing how to protect against HIV when having sex with a man, as a man, would have saved lives. We will never know which of those schoolboys were later lost because of this. The silent epidemic.

I wish a teacher had taught me how to say no to a man wanting sex. That I was allowed to, that it is not rude to, that boundaries can be heard.

This wave of understanding came too late.

I wish had been taught that, aged 16 – five years after the introduction of Section 28 – when I ventured out into gay bars and clubs, older men would not have been taught about boundaries either. Theirs or mine. That when you deny an entire community oxygen its members can wither or, sometimes, lacerate their own.

I wish I had been taught how to come out. What words to use, where best, when best. Why it might stop you killing yourself.

Two years after Section 28 became law, aged 13, I sneaked out of my parent’s house and walked through the village where we lived to shops nestled next to a red telephone box. In my hand were coins saved up from pocket money. Some were pennies. I pushed a small, sweaty fistful into the slot and dialled a number I had found – I don’t know where. “Hello, Lesbian and Gay Switchboard, how can I help?” the voice said. That was all I needed. I replaced the receiver. I just needed to hear the sound of someone else like me. It meant that I existed.

Did Margaret Thatcher, the prime minister responsible for Section 28, think about little boys like me? Could she have imagined what she was doing? That her legislation would not “save” me from homosexuality but send kids outside their schools and homes – the environments designed to raise and protect – gasping for answers? Many, underage, looked in toilets.

That phone call gave me my first oxygen. The next gasp came the following year.

I wish I had been taught not only how to come out but also how transformative it would be. That on one day in 1991, aged 14, telling three close friends “I’m gay”, in a paroxysm of need, would begin to fill my lungs. That this would equip me for life ahead. And that coming out gets easier – a muscle that builds with each rep.

The lesson could have included what happens when you don’t say those words, how the closet strangles and poisons into a complete theft of a life. We could have learned how many have been stolen in this way: history’s greatest heist.

I wish I had been taught how to deal with homophobic bullying at school. Compared to many I was lucky. It was minimal. That is, if you consider hearing boys say, “Don’t touch him, you’ll get AIDS” as you walk past to be minimal. Or if you consider teachers calling you a “big girl’s blouse” to be minimal. Such lessons could have informed other pupils what ostracism does. A clutch of organisations now do this in an attempt to lighten Section 28’s long shadow.

I wish teachers had given me lessons on how this bullying would manifest in later life, to prepare for what was to come, to know that even 30 years later people would still shout abuse in the street. Now they also do it through cyberspace.

I wish I had been taught what to do when someone, or a group of people, chases you down the street threatening to attack you because you are gay. I ask because the police were never much help. Is it best to retaliate? Or to run? Many found out too late.

I wish I had been taught how to cope when you don’t escape violence. No one could have prepared me for what it would be like to have my face sewn up. But someone could have told me that I would survive.

A few years ago, a colleague sought my advice on her teenage gay son: What should she do? How best could she equip him? I told her of the dangers that can face young LGBT people: that we can go from silence, which still exists, into a gay scene for which we are totally unprepared and arrive often with underdeveloped self-worth. Or none. That she could try to accompany her son to bars, or foster enough trust in him that he tells her what he experiences there. To be honest about sex and drugs.

I wish I had been taught what it is like, when you are a teenager, to be surrounded by intoxicated adults, some of whom do not have your best interests at heart.

I wish I had been taught that others in your community will drink, take drugs, and smoke more – and why. To learn of the connection between the early hostility we face, the silence we endure, and the self-destruction that follows. Why we experience more mental illness. Where to go for help.

I wish a teacher – and we had gay ones at my school, I later discovered – had prepared me for the gay scene in the mid-’90s before effective treatment transformed HIV: seeing Kaposi’s sarcoma – the black blotches of AIDS-related skin cancer – on people’s faces. Seeing young men in wheelchairs whose fate was tacitly understood by everyone there.

But most of all?

I wish a teacher – just one – had told me what incredible experiences would unfurl all because I was gay: oppression’s inversion. The outrageous fun, the dancing on podiums in ridiculous outfits, the being as one with others like you. The people you would never have otherwise met. The connections in alien places made from common understanding. The deep love of gay friends, who would carry you through, sometimes literally, who would show up, hug, cook for you, hold your hand in the hospital, who would make you laugh with the humour that pivots from pain.

The sex. My god, if someone had told me at 15 what unspeakable bacchanal awaited, it would have ushered me through the darkness with slack-jawed anticipation.

I wish I had been taught what incredible people LGBT people are. That as I grew I would see tenderness, courage, fortitude, and spirit in dimensions unquantifiable. That when under attack, we will put aside differences and fight – or simply give bigotry the finger before sloshing back another gin, thank you very much.

Had I known, I might have wanted to live.

There is one moment about which I wish I could have been taught, however impossible. Although a specific incident, its resulting feeling is shared en masse by LGBT people every year on a particular day.

This day came, for me, in April 2009. All morning and afternoon I had been on a journalistic assignment, undercover at a conference for people who want to “cure” gay people. The proceedings included lecture after lecture – including demonstrating this on a poor young man – about how to reverse the “evil” of homosexuality. It was a safari of studied hatred. Afterwards I made my way to Soho and stood outside the Admiral Duncan, a gay pub where, 10 years earlier, another man who hated LGBT people, David Copeland, had planted a nail bomb, killing three and injuring 79.

I held a drink in one hand and looked out. As I stood on Old Compton Street – London’s most famous gay street – and watched LGBT people walk past, I saw young men holding hands, older lesbians with pushchairs, people from different races and classes, a leather guy in a wheelchair, a trans woman striding by, all casually going about their business. I thought of the hatred we encounter, from school age to old age, how we carry on, and I felt in every cell and pore an intensifying of something building for years and now outpouring in tears: pride.

I might not have believed a teacher who told me that I might one day feel this. But I wish someone had taught me that I would need to quickly accumulate some pride, from somewhere, simply to survive. I wish someone had told me how much armour I would need. Not least for what lay – lies – beyond the personal: the political.

I wish someone had taught me how much we would have to fight just for the basics. Just, for example, to have the same right to being blown up on enemy territory as straight people. Let alone the right to say, “I do.” It would have been helpful even to know how bittersweet every blood-sweat-and-tears victory would be. How fast everything would change, yet how slow it would feel. How, beneath the surface of public life, despite all those coming out and all the laws changed, so many kids at school would still be kept in the dark, still taunted.

I wish someone had prepared me for what some members of the press, politicians, and others would still say about LGBT people three decades later. The tirades bellowed in the House of Commons against same-sex marriage. The bile now spilled about those whose gender identities do not conform. That trans people would be the new bull’s eye.

We could have made plans.

History’s lessons, though, scream and scream. Particularly outside the West. They screamed in 2013 when Russia first enacted its own facsimile of Section 28, prohibiting “propaganda of nontraditional sexual relationships”. Instead of simply teachers, this (also in its vagueness) silenced everyone. Violence soared. They screamed that same year in Nigeria when the Same Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act made any same-sex cohabitation punishable by imprisonment, along with – also by the law’s haziness – even belonging to a gay group or holding hands in public.

History still screams. Thirty years on from the law that silenced, there is still no mandatory sex and relationships education for all that covers homosexuality, gender identity, and how to navigate any of it. Our children remain unprepared for a world that, in many quarters, tells them not only “That is not sex” but also – in laws, hate-speech, and bloodshed ricocheting across the world – “That is not love.”