The UK is leaving Europe. While we will still play some role in European affairs, when it comes to the wider political and legal picture the UK is saying: "We're alright, Jacques."

Long before the UK voted to leave the EU, the government was already busy planning to rescind a key plank of the country's involvement in the European project: the part involving human rights.

Our membership of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) guarantees us many fundamental rights and freedoms, such as the right to privacy and freedom of speech, and was enshrined in UK law by the Human Rights Act (HRA) in 1998.

In 2010 David Cameron proposed to abolish the HRA, and his 2015 Tory manifesto committed to replacing it with a British "bill of rights". Theresa May reaffirmed in April that the government will seek to take Britain out of the ECHR, although in a speech as part of her short campaign to become leader of the Conservatives she suggested it wouldn't happen in this parliament due to a lack of support in the House of Commons. Nevertheless, for Eurosceptics, the convention is a classic example of European meddling in British laws and British affairs.

But the roots of the convention may surprise some: The charter was inspired by Winston Churchill, and its drafting in the late '40s was led by Tory politician Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe, a talented barrister who had prosecuted Hermann Göring at the Nuremberg trials in 1946.

Nuremberg looms large in Maxwell-Fyfe's life and work. The rights and freedoms of the ECHR were an indirect result of him witnessing evidence of the evils of the Third Reich and doing his best to prevent it happening again. The convention has been ratified by 47 states and affects the lives of 800 million people. Currently, the only European states to lie outside it are Belarus and the Vatican.

As some observers pointed out during May's recent Conservative party conference speech – in which she railed against "activist, left-wing human-rights lawyers" – it's ironic that the current Tory government is essentially undoing the work of a Tory.

So who exactly was Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe, and what does it mean that the UK is about to walk back from his legacy of shared continental rights and freedoms?

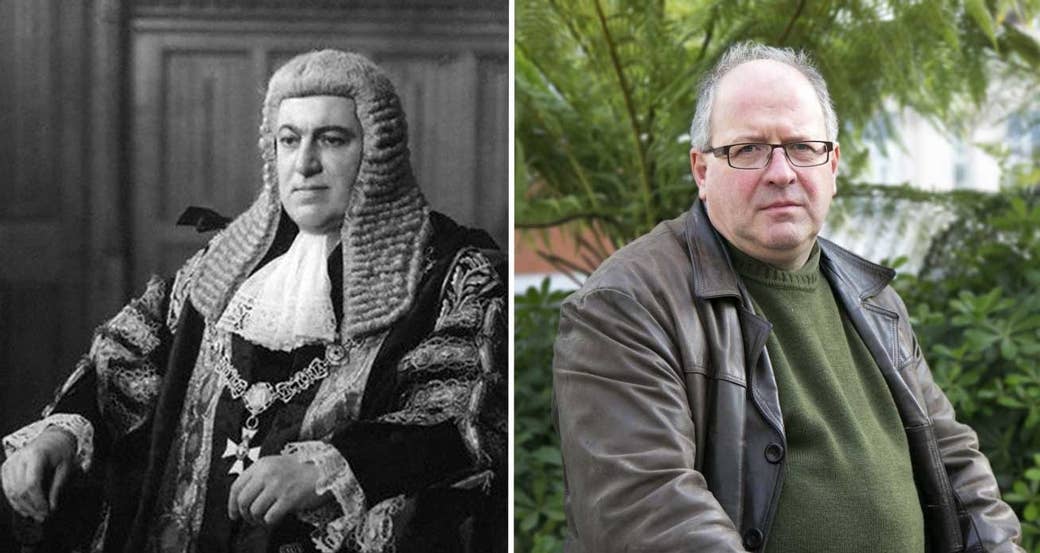

Now in his mid-fifties, Maxwell-Fyfe's only grandson, Tom Blackmore, clearly resembles his grandfather.

A theatre director and filmmaker who made educational films in the 1970s and '80s, including some with John Cleese, he has dedicated most of the last decade to preserving and promoting Maxwell-Fyfe's legacy.

Sitting in a café in Hammersmith, west London, Blackmore speaks with all the vigour and passion his grandfather had all those years ago. For Blackmore, the Tories of today are unrecognisable compared to those of the postwar era.

"There is no conceivable way that Churchill and Maxwell-Fyfe would be part of the modern-day Conservative party," he says.

And as for Brexit and our proposed departure from the ECHR, "I don’t think people do realise what’s happening [to human rights law] – we’ve had an extraordinary period of change. I just feel guilty for my generation making such an arse of it.

"I know that a lot of people are alarmed by the pace of digital change, while some are not really worried about Europe but other [issues] that they can’t possibly get their heads around. But it’s no excuse to get angry and start mucking around with people’s rights."

While she was home secretary, May argued that the ECHR had been frequently "misinterpreted" and had led to British judges' decisions being overturned. The deportation of Islamic extremist Abu Hamza was delayed by four years as a result, she said.

But why do Blackmore and other human rights campaigners want us to stay in the ECHR? The 2015 Conservative manifesto promised to "remain faithful to the basic principles of human rights", while taking a "common sense approach".

A British rights charter would, it said, "stop terrorists and other serious foreign criminals who pose a threat from using spurious human rights arguments to avoid deportation".

Blackmore is having none of it. "The concept of human rights is inalienable and universal," he says. "And to replace it with civil rights, which in effect is what you do if you move to a British bill of rights, they are given to you by the government."

In 1998 Blackmore received a stash of 205 letters written by Maxwell-Fyfe to his beloved wife Sylvia, including many written during the Nuremberg trial in 1946. The letters, which the family thought had been burned, were found intact in the basement of a London law firm. Since 2009 they have been at the Churchill Archives Centre in Cambridge.

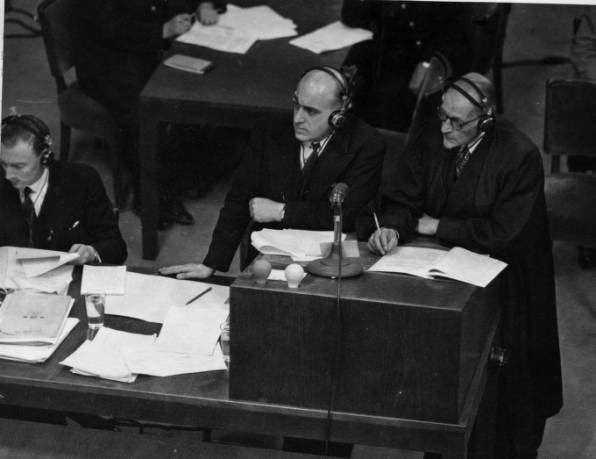

Maxwell-Fyfe would send Sylvia two or three letters a week, containing heartfelt messages alongside schoolboy-like descriptions of the monstrous defendants he cross-examined. Göring, the former head of the Luftwaffe, was referred to as "fat boy" and "slap-happy Hermann".

"The cross-examination of Göring brought [Maxwell-Fyfe] into the public’s attention, a lot of people still wanted to fight the war then," says Blackmore. "And in consequence if you spend a year looking at that level of atrocity and evil, he thought it was a good idea to put in place something that might protect basic freedoms beyond that."

The evidence relating to the Nazi concentration camps profoundly affected Maxwell-Fyfe. In one letter he related how it made him think of his own 7-year-old daughter, Mo, writing:

"When one sees children of Mo's age and younger in this horrible place and the clothes of infants who were killed, it is worth a year of our lives to help to register forever and with practical result the reasoned horror of humanity."

Blackmore thought about turning his grandfather's letters, along with poems that had inspired him, into a book or a stage play. Eventually, working with his wife, Sue Casson, a composer, Blackmore created Dreams of Peace and Freedom, a tapestry of spoken word and song that links Maxwell-Fyfe's role at Nuremberg with the ECHR's creation.

"It’s a disaster for Maxwell-Fyfe that he dropped dead so suddenly [in 1967]," Blackmore says. "I feel like I’m doing the last 20 years of his life."

Modern observers may fail to grasp how necessary European integration and human rights laws were considered to be in the wake of the war. The continent was still reeling from Nazi rule and the western democracies were increasingly uneasy about communism in the east, despite the Soviet Union's crucial role in defeating Hitler.

Now in opposition, the Conservatives became the cheerleaders for the European project, with Churchill famously calling for a "kind of United States of Europe".

When Churchill presided over a congress of more than 700 parliamentarians from across Europe in 1948 to discuss the creation of a new political union, the British contingent took on the task of drafting a human rights charter.

Maxwell-Fyfe, solicitor-general during the war, was brought in to make it happen, alongside the likes of French resistance leader Pierre-Henri Teitgen and Belgian legal expert Fernand Dehousse. It was agreed that the list of rights must be binding, that the treaty must be adopted by different countries, and the whole thing would be enforceable through a court of human rights.

Not everyone was a fan: Then, as now, many UK politicians were concerned about what the convention meant for British sovereignty and the sanctity of English common law. The postwar Labour cabinet supported it reluctantly.

After having just spent a year reviewing the atrocities of Nazism in great detail, Maxwell-Fyfe believed that human rights laws to protect the liberty of the individual against the tyranny of the state would be how people would defeat totalitarianism in future.

At the convention's signing on 4 November 1950, he said: "Some may say that it is of doubtful value that the democratic nations should reinforce individual liberty among themselves and leave the totalitarian states untouched.

"We do not accept this pessimistic view. We consider that our light will be a beacon to those at the moment in totalitarian darkness and will give them a hope of return to freedom. Further, the Convention need not only be a test of membership … but also a passport of return to our midst."

Born in May 1900, Maxwell-Fyfe was variously appointed home secretary, lord chancellor, attorney general, war-time solicitor-general, and Tory peer over the course of his political career, and was also a successful criminal barrister and judge.

As MP for Liverpool West Derby, he would attend court during the day and then travel to London to attend parliamentary debates during the evening, before working through the night and catching the train back to Liverpool in the morning.

He was deeply proud of making it to the top of politics without having either money or influence to start with. The son of two teachers from Edinburgh, he never owned a house.

He died in 1967 from a heart attack, after suffering poor health following an injury he sustained in an air raid in 1940.

Maxwell-Fyfe is well-regarded by liberals, historians, and socialists. Sadiq Khan, now mayor of London and himself a lawyer, declared when he was shadow lord chancellor that Maxwell-Fyfe was one of the left's favourite Tories.

"So, it seems ironic that the convention, overseen by a British lawyer who held four offices of state in Churchill's government, is now being attacked by Tory MPs as an assault on Britain's identity and values," Khan wrote.

Maxwell-Fyfe's record as a human rights reformer was not perfect. He advocated the death penalty and failed to support gay rights. While his views on these issues were mainstream in the 1950s and 1960s, they have, in the eyes of some campaigners, tarnished his reputation as a liberal reformer.

He set up the Wolfenden commission, which concluded in 1957 that homosexual acts between consenting adults should not be a crime – but refused to support its findings.

Blackmore acknowledges that Maxwell-Fyfe never quite "made the leap" to supporting gay rights, but says a quote often attributed to him – "I am not going down in history as the man who made sodomy legal" – was in fact said by fellow Conservative Robert Boothby.

"Reforming politicians never reform enough and fall short of people who would like them to reform further," says Blackmore.

"Don’t get me wrong, Maxwell-Fyfe didn’t back Wolfenden in the House of Lords. It was passed three years later and he didn’t make that final leap.

"The fixation, if he had one... He was very concerned about the proselytising, predatory nature of it – what we’ve discovered now is that that’s not a homosexual feature. It’s more complex than it looks, but he certainly didn’t make the step of supporting [gay rights]."

So, what is it like to be the descendent of someone who did so much to secure European rights and freedoms and see the UK turn its back on them?

"In the end you have to do something about it and make sure it doesn’t happen," Blackmore says.

"We have to stop what’s happening. I respect the referendum, but had the referendum been 52-48 the other way they [Brexit supporters] would have said, ‘This has been so close, it’s definitely not a finished story, we must come back to this again.' I am claiming that right."

Does that mean there should be a second EU referendum?

"I don’t care how we do it, but we should find a way of changing people’s minds and getting a mandate so we don’t give up on [human rights]. This is not saying we can’t reform and change the EU through law – there are all sorts of things wrong with the EU, and this is a good opportunity to do that.

"The thing that causes me to feel queasy is that the view that what happened in Germany could never happen here is wrong. Maxwell-Fyfe said all the people at Nuremberg would not have believed 10 years earlier that they would do the things that they did. Not one of them would have believed it."