The first thing you notice is the smell. Or rather, the lack of it.

Stood 20 feet below the ground, knee deep in fetid water, you quickly realise that the things you feared most about visiting a live sewer – being overcome by the stench, wading through excrement, being attacked by mutant alligators – aren't really an issue.

In fact, because London's 150-year-old, 67,000-mile sewer system combines rainwater with water from baths, sinks, dishwashers, and washing machines – yes, as well as sewage – 98% of what you find in a sewer is water, most of which is relatively clean.

The thing you worry about most when you're down there is not falling over.

BuzzFeed News was invited on this most unconventional of trips by Thames Water to mark Sewer Week, an annual event to promote the company's year-round work keeping the sewers flowing. It's the only week of the year when the media and members of the public are invited down to see the system for themselves.

People interested in the complex, cavernous network of tunnels, sewers, and chambers that criss-cross underneath the capital apply in their hundreds to take part – there is even a waiting list. It's said that these sewers have some of the finest architecture and brickwork in the country, and hardly anyone ever sees it.

BuzzFeed News' correspondent and photographer are first treated to an hour-long lecture on the history of sewers.

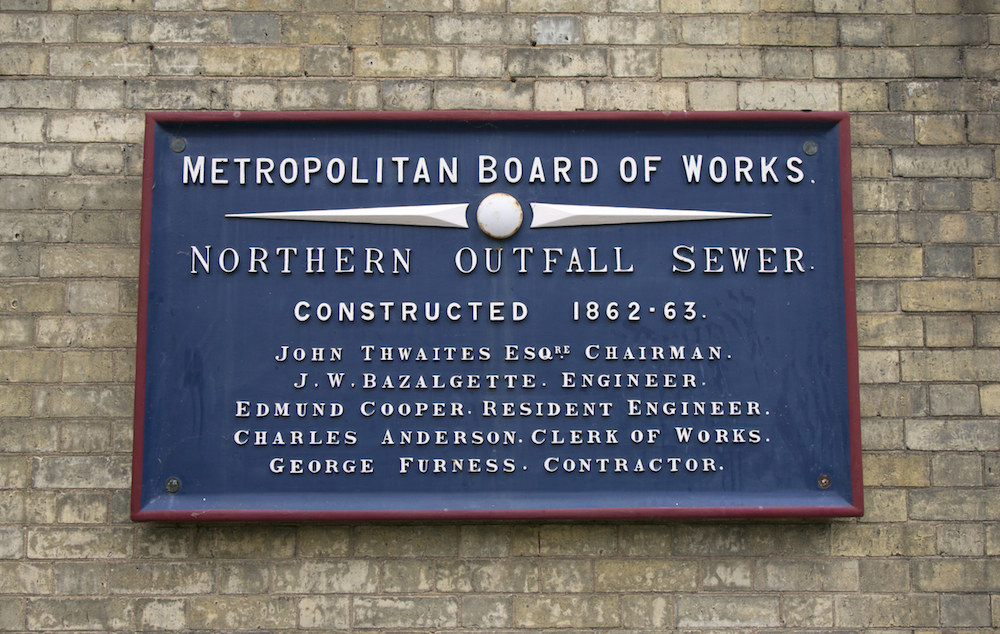

The talk, from sewer expert Ben Nithsdale, is actually interesting: Basically, we still have the same sewerage system that was built in 1853–73, much of it designed and constructed to extraordinarily high standards thanks to Sir Joseph Bazalgette, a visionary engineer. There are only two pumping stations because the tunnels are designed to flow downhill, on London's natural north-to-south slope.

The protective gear you need for entering a sewer consists of two pairs of gloves, some thick woollen socks, some enormous waist-high boots, a white disposable boiler suit, and a hard hat. We are also provided with a "turtle", a one-use oxygen mask to be used in emergencies. Wearing our gear, we descend into the dank, dark cavern of the sewers at Wick Lane, about a mile from the Olympic Stadium.

At the bottom of a steel ladder is three feet of water in a 150-year-old tunnel not more than four metres wide. There is no natural light apart from the occasional shaft leading to the surface. The sewermen leading us have headlamps that illuminate the intricate brickwork, which was all cut and laid by hand by workers in dangerous conditions.

Underfoot is silt and gravel, washed in during storms and heavy rain. The current is alarmingly strong and balancing is tough work.

"People are always surprised by the smell," says Nick Fox, operations manager at the Wick Lane depot. "They think they're going to be wading through cattle slurry but it's not like that.

"These are Victorian building techniques at their absolute best – it was all hand-built, with no machines.

"These tunnels have been here for 150 years and I see no reason why they wouldn't be here for another 150 years. If that was the case for new homes being built now, I would be surprised."

Flushers have been working in these tunnels since Victorian times. It's their job to keep the water flowing at all times. When there's a storm the water level can double, causing all kinds of problems.

People flush a ridiculous array of things down their toilets, says Fox, including mobile phones, wedding rings, money, toys, and much else besides.

Some keys someone flushed down their toilet, now hanging on a hook in the sewer, and a necklace.

But their biggest enemy is cooking fat and wet wipes. These are the things that form fatbergs, the disgusting, enormous blobs of litter and congealed fat that form against sewer walls and openings and – if left to grow – can block entire tunnels. Thames Water says it spends at least £1 million a month getting rid of them, which is normally a grisly manual job involving a high-pressure water jet or, in extreme circumstances, a shovel.

In September 2014, a fatberg under Shepherd's Bush Road that stretched over 80 metres required a large team to dispose of it. But that was nothing in comparison to one discovered in Kingston in 2013 that weighed an estimated 15 tonnes. A fatberg in Chelsea in 2015 cost £400,000 to remove.

"It says on the packet that they [wet wipes] are flushable," says Fox. "But you can flush half a house brick down the toilet – it doesn't mean you should."

Fox wants people to let their Sunday roast fat set overnight and throw it away. "But fat can just flow through or get burned away," he says. "It's the rags that stick to everything."

Rats don't get spotted in this section of the sewer very often. Apart from a dead one lying on a pile of rubble, that is.

They tend to be more in the West End, we're told, around Trafalgar Square and the surrounding area.

And what about mutant alligators? "No, never seen them," says Fox, "and no Ninja Turtles either. I don't think many men would come down here if there were mutant alligators."

One surprising aspect of the sewers is that you may well rely on them for your internet connection. There are hundreds of miles of fibre-optic cables down here, serving homes and offices across the city.

These started being attached to the ceilings and walls of sewers in 2003, in a clever piece of industrial thinking. Laying cable under roads takes up to a year of planning and can cost hundreds of pounds per square metre. The sewers are a handy alternative.

We also heard about one of the real reasons Thames Water invited us here, to promote the Thames Tideway Tunnel – a vast, seven-year, £4 billion infrastructure project to build a new 25km sewer across London that will be as wide as three London buses.

The Tideway will capture nearly all of the 18 million tonnes of sewage that otherwise gets pumped into the river when the existing sewer system can't cope with heavy rain. Plus the sewers were built with 2 million people in mind rather than London's current population of over 8 million and more capacity is needed.

Residents along the route of the tunnel are less than pleased by the prospect of the disruption the building work will cause. But the Tideway company, a joint venture independent of Thames Water, points to a number of riverside developments the scheme will bring, such as an extended public pier at Blackfriars.

Back above ground, we're treated to a viewing of the treasured cabinet of Things People Have Flushed Down the Toilet, as lovingly curated by Thames Water staff.

Alongside the wedding rings, toy bus, and coins are various types of bullets, a watch in good condition, a $100 Jamaican note, and glass bottles that have somehow survived. Because of the way the sewers flow into each other, these could have come from anywhere in the city.

Tony, who helped us into our gear, says the best thing found was an old Nokia 3311 phone that he claimed was still working.

As a palate cleanser, after undergoing possibly the most disgusting yet oddly fascinating experience imaginable, we are then shown around the Abbey Mills pumping station next door to the sewer works. Still operational, this was built by Bazalgette and co in 1865.

A grand gothic hall, its nickname is the Cathedral of Sewage and Thames Water are very proud of it. It's been used as a location for films such as the Christopher Nolan-directed Batman Begins, in which it doubled for Arkham Asylum. Musicians including Coldplay and Paul McCartney have made promo videos here.

Only after the tour ends does the feeling of nausea start to set in, as the realisation of what we've just walked through hits home. But it's not often you get such a candid glimpse into the subterranean London beneath our feet, which contains vital services that haven't changed much since Queen Victoria was on the throne, things we unknowingly rely on every single day.

If you'd like to visit the sewers yourself, you might like to know that Thames Water is currently taking applications for Sewer Week 2017.