Like most children raised in the '80s and '90s, I was awarded for nearly everything I did — things that were not particularly accomplishments, like completing my elementary school’s field day, or showing up for a swim meet. Most of those shiny PARTICIPANT ribbons eventually made their way into a landfill, but there’s a collection of plaques and trophies that have nestled into every bookshelf I’ve ever owned.

"NORA MCINERNY, MOST IMPROVED," they proclaim in all caps, telling the world that while I was never the very best at basketball, or volleyball, or golf, or really any athletic endeavor of any kind, I at least got better at it.

It’s been [redacted] years since I’ve retired from high school sports, and I’m still not the most physically coordinated person in the world. I run into my dining room table at least twice a week, even though it’s been in the same place since I moved in (because I put it there). I frequently do not “think fast” enough when someone throws me a set of keys, a can of gluten-free beer, or a baseball. I have fallen off two treadmills in my lifetime. I do work out pretty consistently, and because people who work out want to tell you specifically what they do, fine: I run, I go to a gym, I take a barre class every week, and I occasionally get on an exercise bike with 50 strangers and bike to nowhere while listening to techno music.

I’m not good at working out.

But I’m not good at working out. I am not the kind of woman who walks into a room of free weights and says to herself, “Let’s do this!” Instead, I’m the kind of woman who walks into the gym I’ve been going to for well over a year, looks at the board and says, “OK, can you remind me what these things are? I don’t remember a split squat, did you just make that up?”

But even if I'm not good at working at, I do love it. I love every single step of every painfully slow mile I run, even the ones where I get passed by men at least twice my age. I love every humbling moment of barre class, where my legs shake uncontrollably and I have to focus on not peeing my pants. (What. I had a baby! Three years ago.)

And yeah, part of that is the endorphins, but part of it is the reminder of what it means to be alive, and that’s struggle.

We all love to see an unlikely victory (how many times did you watch Mighty Ducks as a kid?), and we love sharing our own. We post finish-line selfies and personal records, but we’re more shy about the struggle. The struggle doesn’t seem like something we’d be showered with likes and hearts for, but we should be.

Because the struggle is awesome.

I didn’t take fitness seriously until my husband was diagnosed with cancer.

I didn’t take fitness seriously until my husband was diagnosed with cancer. And I mean, I still spend 30% of my workouts talking or filling my water bottle, so I am a work in progress. But the past four years of my life, from newlywed to new parent to caretaker to young widow, have been defined by struggle. By doing things I’ve never done before — from deadlifts to driving my own U-Haul to completely giving up on potty training our son — and completing them no matter how awkward it was to learn, then getting better at them.

My husband didn’t survive his cancer. And before he died, I was his main caretaker. All of my deadlifts and rows paid off, and I could lift and carry him around our house when his own limbs failed him. Not because it was easy, but because it had to be done, and because I was strong enough to do it.

A wise man at my gym who goes by Cardigan Mark was listening to me complain about push presses (which he had just demonstrated to me and my goldfish brain for possibly the hundredth time). The weights, I complained, were heavy, and the workout was hard.

“That’s the thing,” he said. “If you want to get stronger, things have to get harder.”

He was right, in a way that annoyed me but not so much that I didn’t rush to scribble that down in my notebook between sets.

I was not good at any of the things I'd gone through over the past four years. I had never before been in love with a man with cancer, or married one. I’d never seen one brain surgery scar, or been allowed to remove someone’s head staple with a staple remover that I swear was from OfficeMax. I’d never had a baby, I’d never been to Disney World, I’d never watched someone die in my arms.

But I did all of that — and came out of each of those experiences as a different version of myself.

I’m stronger now than I was four years ago, four months ago, four days ago.

I’m stronger now than I was four years ago, four months ago, four days ago. That’s the power of the struggle. It’s not an instant mastery; it’s a reminder that every hard thing you do is eventually a hard thing you’ve done, that all of the things you’ve dreaded will be memories you look back on from the place they helped you reach.

I know that I really just keep my trophies around because they feed my unending hunger for approval and validation, like real-life versions of likes and hearts. And also because they aren’t exactly the kind of thing you can donate to a thrift store. But let’s pretend for a moment I’m a little bit deeper than that, and say that they remind me that life isn’t about perfection, but about getting better, a little bit at a time. The struggle won’t give you the internet high of likes and faves and hearts and comments, because those things are easy to get and are utter ephemera. Hard things are hard, and the only real award you’ll get from going through any of them is a hard-won sense of self, a quiet sense of validation you can only give to yourself, after you’ve been through some shit together. And, if it were up to me, a trophy.

***

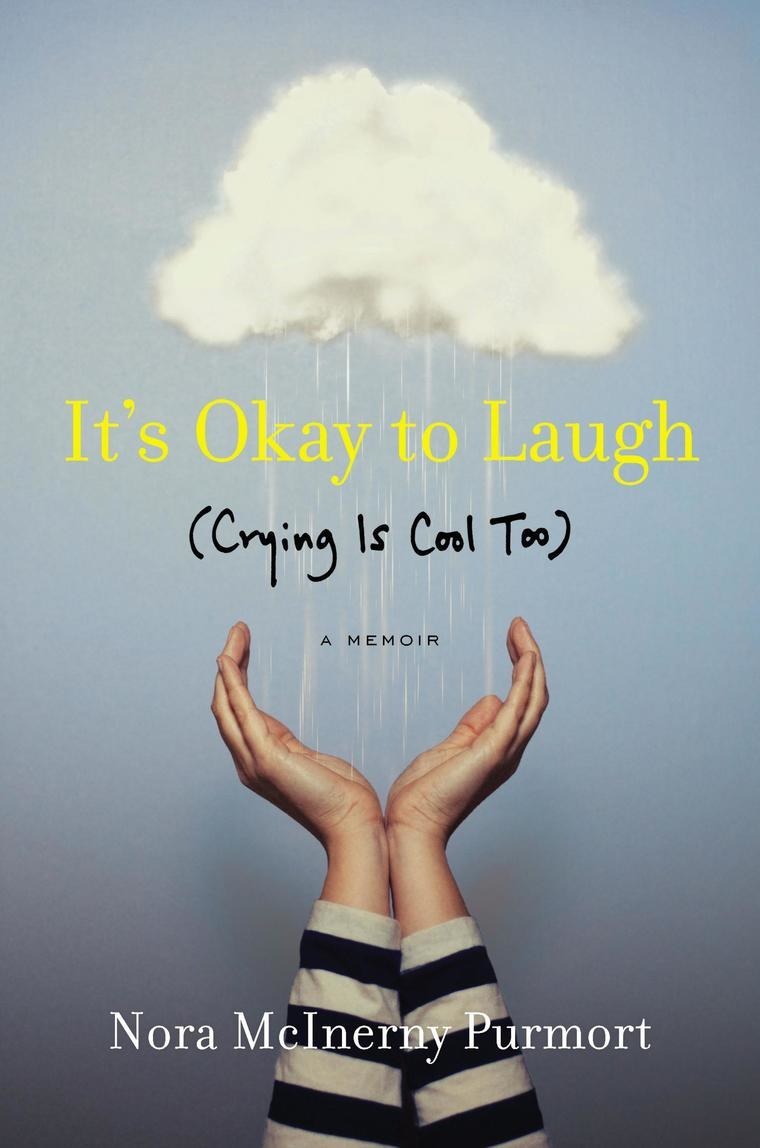

Nora Purmort is a frequent contributor to Elle.com and Cosmo.com. Her memoir It’s Okay to Laugh (Crying Is Cool Too) comes out tomorrow.