"Head On With My Hate/Into the Lights Ahead..."

I already knew I loved their music, the whole catalog. I knew this because that summer had been the worst of my entire life, and Foo Fighters' records gave me hope that stretched somewhere beyond myself. I listened to them on loop, at deafening volume, as I drove through my small suburban town on pizza delivery shifts.

Squinting at numbered mailboxes in the dark and the constant smell of cheese and garlic were a lot easier to tolerate with There Is Nothing Left to Lose in the background, a reassurance that something was just over the horizon if I could hold out.

"Head on with my hate/Into the lights ahead…"

Watching that broadcast, I realized this music wasn't just a distraction or a musical antidepressant. This was my roadmap. This was my chance.

Not long after, Foo Fighters were announced as the third and final headliner for Lollapalooza in Chicago on August 7, 2011. I had never been to a music festival before, but this seemed like the perfect time to start. I booked the last empty bed in a hostel (also a first) resolving to drive up the morning of and drive back the morning after. It was almost too easy.

Until my mother announced that she and her fiance were getting married on August 6.

So it was that I danced at my own mother's wedding reception that night, woke up the next morning and drove straight from the middle of nowhere to Chicago, stopping only to park in the seediest garage I had ever seen (when I asked the attendant how much it cost for the day, he paused and said "For you? $20.") I wandered downtown until I found the main stage at Lollapalooza in Grant Park, where I stayed for the entire 12-hour day.

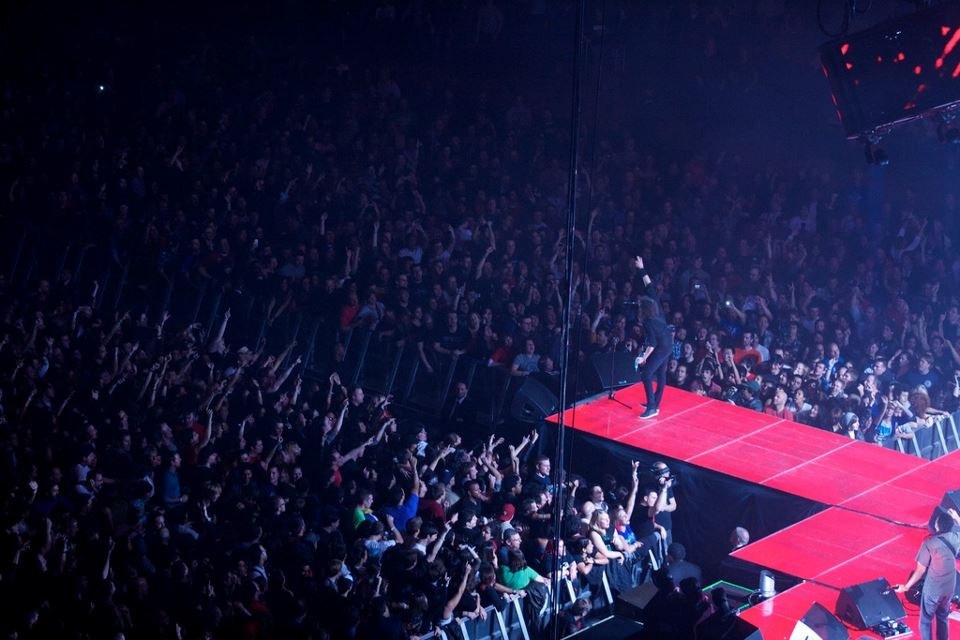

Foo Fighters' set was everything I could have hoped for. Other than the obvious – being an incredibly skilled, dynamic live band - there was an added twist that even the best of coordinators couldn't have predicted: it started to rain. The heavens opened up, and it was a deluge.

And yet soon enough there was this band, running to and fro and completely drenched within moments, as if they didn't have a care in the world. Laughing, as if this was something they'd planned, and totally playing it up.

View this video on YouTube

VIDEO: Lollapalooza 2011, official stream (before the feed was drowned out).

I knew right then that I'd made the right decision. Seeing them again was no question; it was just a matter of when.

I was moving to Boston for college a few weeks after the festival; as if to welcome me, Foo Fighters announced a fall tour through the northeast that November. I spent every last dollar I had on tickets and travel arrangements: Washington, DC; New York, NY; Newark, NJ; and, finally (and fittingly) Boston.

I had no idea what I was doing. I was extremely excited. I had virtually no money left.

My life was about to completely change.

"These Are My Famous Last Words!"

Due to my class schedule, my only option was to fly into the city the morning of that first show. I caught a flight to DC 6:00 am and … I was the first one there. I claimed a spot on the freezing pavement and waited.

I was definitely something of a touring novice. That may be charming to a point, but what it mostly means is trekking through four states with nothing but a backpack and some earnest enthusiasm.

I had no plans between the end of the show and my 6:00 a.m. flight back to Boston. I spent hours asking perfect strangers if they had somewhere I could keep my stuff, having neither a hotel room nor a car. All things considered, I was a pink-haired infant.

Honestly, these fans saved me. They stayed up nights with me, let me sleep on their couches and cots, and walked me through a darkened Newark to the train station.

And they justified my passion for seeing this band, making me feel validated and welcomed. I latched on with both hands to a freedom that I had only dreamed of in Ohio months before, and I refused to let it go.

That's one reason why I was the picture of joy, of unabashed uncool, singing every line at that first show.

I know this because I was just that thrilled to be there, and that blown away by their stadium set and staging. I know this because this first show was in the round; videos showing the front row, featuring my face, can be found on YouTube.

View this video on YouTube

VIDEO: Washington, DC. November 2011.

(That's me with the blue shirt/pink hair, losing my mind, corner barricade. That's Dave Grohl, foreground.)

And I know this because as the pre-encore song rang out and the band began to walk offstage, second guitarist Pat Smear looked out into the crowd, pointed at me, and mouthed, "You rock!"

He tapped the security guard closest to him and handed him a pick, motioning that it should be given to me. I stood frozen for a beat before firing back, without thinking, "No, YOU rock!"

Later, I would catch a stick the drum tech hurled into the crowd. My face hurt from smiling with every new song they played. It felt like a warm welcome - like I was exactly where I was supposed to be. Maybe I had no real plans, no safety net, but I had no fear, either.

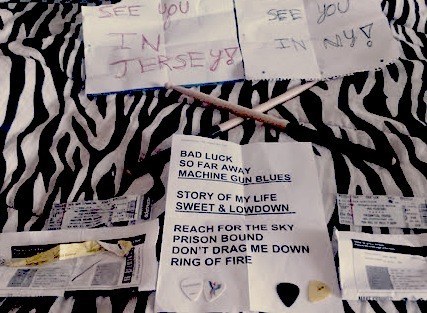

I made front row again in New York, something I felt I had earned after a day of sitting outside Penn Station and, at one point, being made to mop up someone else's urine so that we had a clean place to do so. On the rail I had a bolt of inspiration – I scrawled "See You in NJ!" on notebook paper before the encore, holding it up once again after the show. This earned me a hearty "Fuck yeah!"

But as the encore arrived at that Newark show and with it, my opportunity to make a sign, I suddenly felt embarrassed. It seemed ridiculous to believe anyone in this, or any, band would care whether or not I was going to the next show. I kept my notebook in my backpack.

As the roar of the crowd went up after the last song, Pat looked at me expectantly and mouthed "Boston?"

I must have grinned like an idiot. "Of course!" I yelled back.

But Boston was the last – it was, in fact, the final scheduled U.S. tour date. It was what I had been dreading since that first, baffling night in DC.

I had landed barricade at four shows, in four separate cities; in each one of them I had found new friends, new experiences, and a new sense of accomplishment.

But along with that came a sort of accountability: realizing that if I wanted it badly enough, there was so much more to do – so much more that I could do.

I had never allowed myself to be defined by one thing. From the get go, I patently refused to allow myself to be "just" a student, "just" in Ohio or Boston. By planning that tour, by meeting those people, by finding this band, I had found a way to do that.

“One of These Days the Ground Will Drop Out From Beneath Your Feet….”

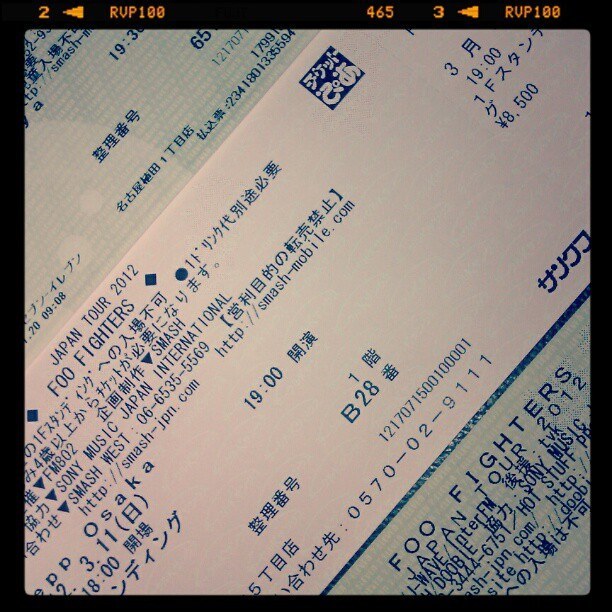

The Japan tour, as it turned out, lined up perfectly with my freshman year spring break. Completely out of money from my summer gig, I landed an on-campus part-time job as a glorified telemarketer, soliciting donations from alumni, storied donors, and in some cases current seniors.

My ultimate, lofty goal was to make the $850 I needed for my round-trip flight. (I remember asking my friend, who had been working full-time for years, if that was even possible. She assured me, with astounding patience, that it was).

I had about two months to make it happen. I put blinders on.

To the point of embarrassing honesty, but with very little exaggeration, I put my heart and soul into planning that tour. I found every hotel, plotted the distance to each stadium, and mapped transit - after all, we'd be travelling between Tokyo, Sendai, Nagoya, and Osaka.

I also discovered that buying tickets to the shows was nearly impossible as a non-resident of Japan. I hired a service to bid for me on the Japanese version of eBay for each of the five shows – seats were in one of several GA "sections," and I had to find the best one.

I would frequently find myself sitting in my French class at 8:00 a.m., phone in my lap, e-mailing someone in an office in Japan, asking them to raise my bid or if I had won. At least once, I hid in a bathroom stall to negotiate. If I could just pull this off, prove something to myself if not everyone else, then it would all be worth it.

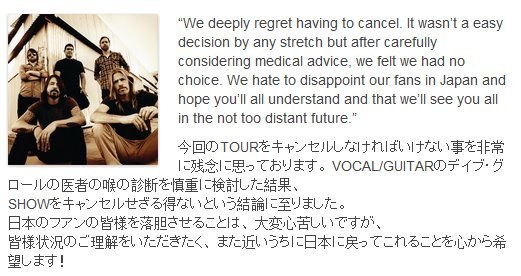

And so it was that about 10 days before we were set to leave, the entire tour was canceled.

I skipped a class the morning that announcement went live; I lay in my dorm bed, muffling my sobs into my pillow in case my suitemates were home. I had told everyone about my work, my plans, and I dreaded telling them this. I posted a lyric from "These Days" that felt dramatically apt:

"One of these days, the ground will drop out from beneath your feet … "

I felt defeated, for a while. But, ultimately – and with the help of my travel companions - that feeling went away.

I was left what became that familiar fire in my belly: what choice did I have? Our rail passes were nonrefundable, as were our plane tickets – but our hotels weren't. We would rearrange. We would see sights. We were going to Japan, band or no band, so we might as well do it right.

As I was zipping my suitcase shut on my dorm bed an hour before I left for the airport, I can remember collapsing onto my bed, laughing out of sheer incredulity. "I'm about to go to Japan," I said, to no one in particular but in the general direction of my roommate, "with two French Canadians and a German who I met in line in Newark."

"That's what I've been saying this entire time," she said.

I like to compare our trip to Japan to the day trip we made, a few days in, to visit the lauded Mt. Fuji. More money than I had to spare and several hours of our day were spent to get some photos of this famous mountain. I remember, as we got closer, our increasing reservations that we couldn't yet actually see the mountain, and wasn't that kind of weird? It was supposed to be big, right?

It was. The cloud cover, as it happened, was simply too dense, the mountain completely obscured.

So what did we do? We found a giant pile of snow and posed as if we'd climbed that damn mountain ourselves.

In a sense, that was Japan.

That was riding a Ferris wheel over the lights of the city, despite our friend's apparently intense fear of heights. That was the surreal experience of listening to Iggy Pop's "The Passenger" as I rode the Tokyo subway, the lights of the city dancing below.

That was discovering the wonder that is instant matcha tea in every budget Japanese hotel room. That was realizing after landing that I had completely forgotten to budget for food. I subsisted most days on rice cakes, one-Yen pastries from the Japanese 7-11, protein bars, and hot, canned coffee from a vending machine.

I allowed myself one indulgence in the form of a souvenir. When we wandered into a pop-up outdoor market in Kyoto, I found in one tiny, candlelit shop a necklace that read "All Or Nothing." I didn't hesitate to buy it.

I realized that, at all costs, I could not let that fire in me ever go out. But still, I did want to see the band …. so Europe, it appeared, was next.

I owe a lot to Foo Fighters' 2012 Japan tour – the best thing I never did.

"I Think I've Found My Place..."

Europe was a sleepless marathon, a daunting, crisscrossing endurance test vaulting five countries, flipping time zones, and braving dizzyingly different weather patterns through August of 2012. It was, somehow, a success and a perspective shift.

I spent three days exploring Venice, from the maze-like streets of San Marco to the white sand beaches of Lido, before watching the band play at a historic country Villa.

I showed up in Belfast with nowhere to stay, ultimately offered a bed and breakfast from which I could walk the cobblestone streets of the city that reminded me of my own Boston.

I braved 92 degree heat and participated in a "These Days" flash mob tribute at Pukkelpop outside of Brussels.

View this video on YouTube

VIDEO: Pukkelpop Festival, August 2012.

Flash mob tribute organized by a group representing Belgian and Dutch fans.

In short, I saw more of the world than I ever thought I would have at that point in my life.

Between shows, I was cut in line for a budget flight by Patrick Carney of The Black Keys, who I would see perform the next day alongside Foo Fighters. Chatting with one of the band's techs at baggage claim after we'd landed, I told him of my hostel-hopping adventure thus far.

In my Nirvana t-shirt and one pair of jeans I was all lightheartedness and sunburn, watching my possessions spin on a rickety carousel. He looked at me with surprising earnestness and said, "You're very brave."

I didn't feel brave, or special, or even particularly unique. The month of planning that this venture required had come with an anxiety that I couldn't shake, haunting my nights and terrorizing my mornings. But once I was out there doing it, living the plans that had tortured me on paper, it felt like the answer to every one of my unasked questions.

At this point, miles and months afield from my last tour, I had more or less reconciled myself with the fact that I was once again just another face in the crowd. That, however, was challenged after my first European show - more specifically when, as I stood on barricade in Prague, Pat looked directly at me, pointed to his head and let his mouth fall agape, as if to say "Your hair!"

This was also a surprise. But so was me showing up in Prague with a fauxhawk eight months after Boston, I suppose.

When the last wave of feedback roared louder than the crowd and the show drew to a close, he walked over to the edge of the stage and mouthed, "What's your name?"

Futilely I repeated "Morgan!" at the top of my voice, only to have him come back with something like "Monet?" We somehow came to an agreement, through miming, that we'd try again at the next show.

After another failed attempt in Belgium, however, at my third show in Northern Ireland I resolved to go back to my old methods: I would make a sign. After his typical "Hi!" and "What the fuck?" greetings, I took my shot, holding up a piece of paper that read, simply, "MORGAN" in red sharpie.

"Morgan!'" he mouthed, hanging his head in either relief or embarrassment. Looking up again, he grinned. "Hi, Morgan," he said.

"Hi, Pat."

It was pivotal, at that point, to realize that even as I stood in a sea of people, somewhere I'd never been, I could find at least one friendly face. It was a sort of validation of the craziest choice in my life like I couldn't have imagined. How could I be anything but proud now, and how could I not go at it with everything I had?

And with that, there was one left to go (as far as my tour was concerned): Leeds Festival.

Even I, in my constant pre-show anxiety, could not have predicted what that was going to mean.

By the time the third-to-last band came on stage at that festival, after a full day of standing in the elements (and lining up, and running, and standing around some more) the worst crush of my life began. I felt like I had been embraced by every one of the festival's 85,000 attendees.

When Foo Fighters were set to come on as the last act, everyone I had been with through the day had left by request or was required to, if their pain could no longer be ignored; a friend suffered at least one broken rib from the experience. But I had come all the way from the States for this, I'd fought for this spot. I was not about to miss this set for anything.

And then Foo Fighters came on stage, and Hell fully consumed the earth.

It started to rain, I hadn't been able to reach my bag for hours, and the stream of crowd surfers – hard to dodge considering I could barely move – had become relentless. And yet, as always, Pat looked out and saw me. I got the biggest "What the fuck?!" of the tour and, after a beat, "Hi, Morgan."

I tried my best to maintain my trademark enthusiasm, but that proved impossible. My efforts to keep up appearances weren't as foolproof as I'd hoped, either, as his greeting soon devolved into concern: as I hunched over for what could have been the hundredth time, shoving back against the crush with my shoulder, Pat looked out into the crowd again: "Are you okay?"

What I lacked in strength in that moment I made up for in pride. It felt like all I had left.

I looked back at him – grimacing, I'm sure, despite my best efforts – and made a so-so motion with my hands. But after a few songs – none of which I could remember, if prompted – and yet another crowd surfer kicking overhead, with cold clarity I was suddenly resigned.

No matter what I said to save face, I simply wasn't having fun, and I was probably in some kind of danger. It was time to call it in.

I stopped looking at the stage entirely and gazed out, eye-level, as security darted back and forth trying to stop the mad flow of people escaping the pit. I couldn't even find someone to make eye contact with, to just convey that I need a hand to get out.

And in that moment of helplessness, I finally saw another friendly face: none other than the band's head of security, who had introduced himself to me in Prague after noticing the sore-thumb obvious foreigner that I was. He and another official approached me from across the rail. "We're getting you out," he said.

I stared blankly, wondering how he had known what I was trying to do. After a pause, he continued: "Pat wants you on stage."

I was hardly in a position to ask questions. I let go, allowing them to pull me (with some effort) out of the crowd. We walked through security and up a flight of stairs, and suddenly I was side stage at one of Europe's largest music festivals.

They stood me next to his guitar tech's station, which was adjacent to the monitor boards and close enough that guitars could be handed to Pat and the bassist, Nate Mendel, between songs. During one such break, Pat walked over to me and said, simply, "Hi, Morgan."

I pulled him into a hug before I could stop myself, still coursing with adrenaline from what felt like my narrow escape, and admitted how close I had been to leaving.

"Yeah, I could tell," he said.

I stayed there through the rest of the show, trying to take it all in. I relished the space to dance and jump around more than ever, even as it was partially to keep the cold at bay as I stood in a tank top in the open, frigid air.

But before the traditional last song could even begin, techs were scrambling all over the stage packing up gear. The band had to be at Reading Festival the next day, and apparently there wasn't a moment to lose. I tried to enjoy these last few minutes even as I avoided being hit with rolling road cases.

All too soon, the last chords rang out, the band waved to the sea of people, and all were ushered offstage. I realized just in time that it was probably (and understandably) assumed that I would be at the next show, but I had already committed to being in Paris the next day; this was really it. As I saw Pat moving to walk down the stairs with everyone else, I blurted, "This is my last show!"

"I'll miss you!" he laughed.

And with that, I climbed back down into the muddy pit to retrieve my backpack - which had nearly everything important within it and had somehow survived the chaos that I couldn't – thanked their techs for their kindness, and walked alone down the back stairs, off stage. I wandered across the muddy grounds to a taxi stand, muttering "What the hell is my life?" into the dark.

“Sing In the Congregation!”

I still have no idea what it was that made me so desperate to get tickets for Foo Fighters' 2014 Halloween show in Nashville.

At a one-off gig at years before, Pat Smear had introduced me to a friend as "Morgan, who goes to all of our shows, everywhere." By this point I had reconciled myself with the fact that, really, he wasn't wrong; I had, in the meantime, showed up at gigs in Austin, Texas and Mexico City.

For me a tour lull meant a kind of stasis, a sense of idleness in a lack of preoccupation. Back in school and working two freelance jobs to fill what felt like far too much free time, it seemed I just needed an excuse, a reason.

Arriving at the antique theater that night, with seats arranged in pews and walls adorned with stained glass – definitely a first – I attempted to explain to the women behind me what had led me there from Boston. A few songs in, one of them tapped me on the shoulder, her beer held aloft. "Your boys are amazing!" she yelled with a grin, before turning back to her drink and the show.

I had to agree. They were putting on a particularly raucous live show, shaking the dust from the rafters, their ill-advised monster makeup visibly melting from their faces.

But more than that, I thought about the screening of the city-specific Sonic Highways episode they'd shown before the set, as they would do at all of the gigs on this mini-tour.

I thought about where I was, and how the show, at root, was intended to be a celebration of something much bigger than this band and even this historic venue.

Walking exhaustedly out of the venue that night, I resolved to make the most of it; as best I could, I wanted to experience Nashville.

I walked down Music Row and ducked into any number of Honky Tonk bars that featured live bands, doing my best to keep from belting out "Sweet Home Alabama" alongside everyone else. I spent far too long in several record stores. I got a little bit of adventure. (I also got the flu, but that's another story).

Essentially, in Nashville I reconciled myself with what the Sonic Highways project was actually supposed to be about. With its championing of a place, its people, a culture, a sound, it spoke to so much more than the blurry anonymity that touring (even for me) could so easily become. I had nearly fallen into that trap – of jetting in, seeing a show, and putting down some kind of tally mark that no one else was keeping track of.

I now had stories and points of reference in a new city, public singalongs, and conversations with strangers that weren't strangers anymore. That was Sonic Highways.

That, I realized, was what I had been doing all along. And now I had the best excuse in the world to do it all over again: next, there was New Orleans.

At the House of Blues, just off Bourbon Street, I stood mere feet from the band at another tiny show. Dave Grohl played perched on an amp directly above my head; his guitar threatened to hit me in the face several times throughout the evening, and at one point he walked close enough to the edge of the stage to narrowly avoid stepping on my hands.

I had taken great pains to see these guys from such a distance that I was surely only one of a faceless mass. Somehow, not even three short years later, here I was. It was weird. I felt very, very lucky.

But it felt all the more significant that I wasn't alone in it.

It should hardly need clarification at this point that one reason I travel so far for shows is because it's a sense of liberation, of breaking tethers. It's an exercise in independence. But it's equally true that this aspect of my life has been brightened, strengthened, and at times outright saved by those around me.

That I could head out onto Bourbon Street for original Hurricanes at 2:00 a.m., swapping gig stories; sip Cafe Du Monde's signature chicory coffee to shake off the post-gig drag; run through the streets following a brass band in a wedding procession "second line." That even in this, my independence, I wasn't alone. That was what I got from New Orleans.

And, finally, there was New York City.

I firmly believe that everything I had learned about gigging up to this point was called into question on this venture.

My friend and I were in line for 24 hours, starting the night of December 4. I slept on cardboard, including a makeshift pillow, covered by a sleeping bag. I walked to Duane Reade intermittently for hand warmers and Oreos.

At one point, I accompanied a friend to change into a second pair of convenience store tights in the closest free bathroom: the Customer Service center at a Best Buy across the street. There was what Dave Grohl would later describe as a "riot," due to faulty venue policy and unexpected turnout.

But at long last, during the show that night, the notes of "Congregation" rang out, and somehow, so far from where the song was written, I got it.

Maybe I could get away with studying in coffee shops, taking math notes on cramped American Airlines flights, and listening to lecture podcasts on Greyhound buses. Maybe that was working.

Maybe I could do transcription work and write papers in departure lounges. Maybe I could schedule the earliest flights possible so that I could land with just enough time to make it to class in the morning without having slept.

Maybe somehow I had pulled it off. Maybe learning how to do that, proving I could do that, was what these months had been about.

It was takeoffs and landings and holding my own. It was bus trips and train trips and learning how to pack a gig bag. It was messing up a lot and getting really, really lucky. It was my friends, onstage and off, who were barricade warriors, sleepless champions, protectors and enablers.

It was learning how to expect nothing and appreciate everything.

Against the stage in the Plaza, I got it. And I sang, a huge, stupid smile undoubtedly on my face.

"I've been going through life making foolish plans. Now my world is in your hands.

… Sing in the congregation."

“This Was No Ordinary Life!”

That would have been a fitting ending, in a way - but if I've learned anything over these last few years, it's that there never really is one.

There was the secret Record Store Day show in rural Ohio: sleeping in a rental car outside of a record store, waiting for a 200-cap makeshift show in a strip mall. There were rips to London and Edinburgh, where I had expected stadium shows and found none (Dave having broken his leg in Sweden not long before), and I took in a Foo Fighters tribute band instead.

There was Citi Field in Queens and Fenway Park in Boston, the appearance of the ridiculous "guitar throne" and the gift of a cymbal that left me speechless after my 25th show.

There was a road trip to Pittsburgh with a fan I had met in line a month before. There was the subsequent, spontaneous decision to road trip another seven hours west rather than back to New York, to see another show in Indiana.

There was blasting "Monkeywrench" down the suburban streets I'd grown up on, and camping out on my uncle's futon. There was the 12-hour sleepless marathon drive back to the east coast, seeing the sunrise in West Virginia and stopping only for fuel and energy drinks somewhere in Pennsylvania.

There was this last show, my 30th, in Memphis. A lifelong Elvis fan, I reveled in the tours of Graceland and Sun Studios, of walking Beale Street and hearing live blues at every turn: the new, exciting and unfamiliar.

And yet the next day there I was, arriving on barricade to a welcome. Techs and crew asking how many shows this was; a knowing nudge from management and staff; a blatant lack of surprise from band members - "Hi, Morgan." "Bye, Morgan." It was the feeling, the confirmation, that in this strange place I was exactly where I was supposed to be.

30 shows, 20 cities, seven countries, four years.

I have a vivid memory of my first Foo stadium show back in 2011, front row corner barricade. Overwhelmed and empowered I threw my first in the air, stood on my toes, and yelled along with "Dear Rosemary." I felt I was sending up a wish, a fervent hope as much as anything else.

"This was no ordinary life!"

I knew then that I wasn't there yet, but I was on my way. I like to think that while so much has changed, that part of me is still there. I like to think that through all of this, I've lived to make that part of me proud. I like to think I'm still getting there somehow.

I wouldn't trade this strange road for anything.