“Being trans is like running away from home.” — Alok Vaid-Menon

I moved to the U.S. from the Philippines when I was 15, where I had been raised as a boy. About a decade later, I started to live as a woman and eventually transitioned. I think of migration and transition as two examples of the same process – moving from one home, one reality, to another.

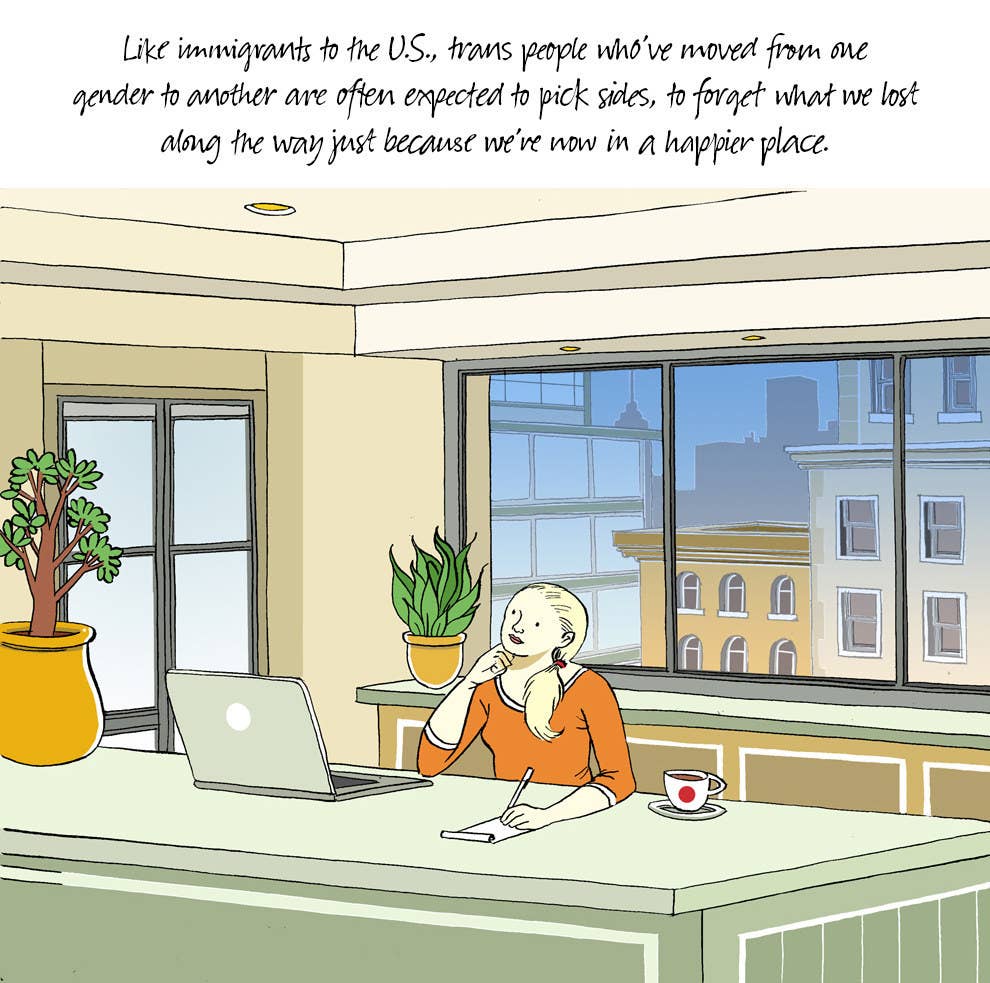

But the two are also similar in a less obvious way. Like immigrants to the U.S., trans people who’ve moved from one gender to another are often expected to pick sides, to forget what we lost along the way just because we’re now in a happier place. There might be immigrants and trans people who are completely happy in their new homes, but I am not one of them. My relation to home, both in place and in gender, will always be conflicted and fraught. And being an immigrant helps me navigate my difficult feelings about gender as a trans person.

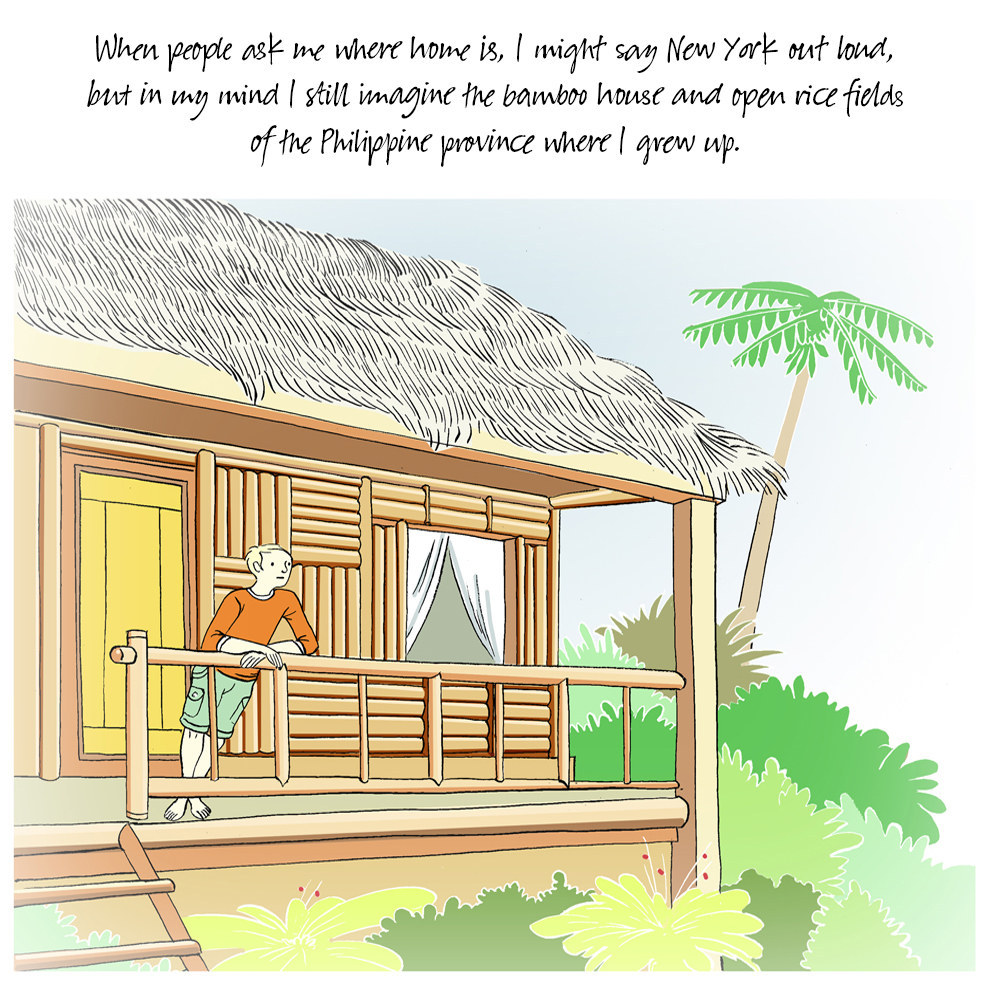

My family immigrated to the U.S. specifically so that my siblings and I could have more opportunities, a better life. I took full advantage and ended up going to fancy schools, getting good jobs, achieving a degree of success I wouldn’t have had if I stayed. When people ask me where home is, I might say New York out loud, but in my mind I still imagine the bamboo house and open rice fields of the Philippine province where I grew up.

I legally relinquished my allegiance to the Philippines once and for all in 2012 when I gave up my passport, reciting a pledge that began: "I hereby declare, on oath, that I absolutely and entirely renounce and abjure all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty, of whom or which I have heretofore been a subject or citizen.” Somehow, even though it happened with less fanfare, I couldn’t help but be reminded of the last time I went to a courthouse, to legally change my name and gender. Just like when I picked between the U.S. and the Philippines, I was also faced with two options, M or F, and I chose to move from one to the other.

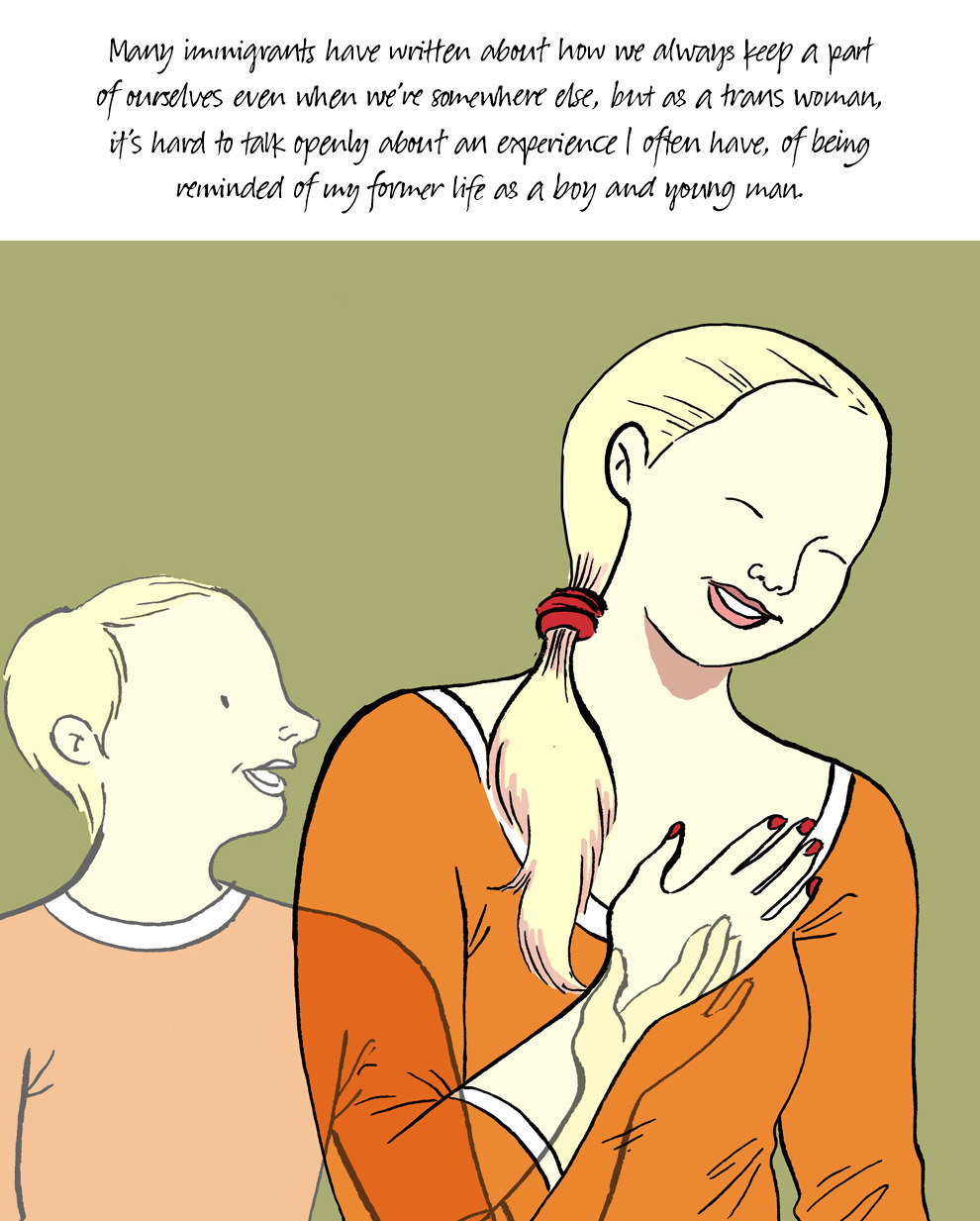

But the emotional truth is a lot more complex than these legal truths. The fact is that I will always be bound to the Philippines, loyal in heart if not on paper. Many immigrants have written about how we always keep a part of ourselves even when we’re somewhere else, but as a trans woman, it's hard to talk openly about an experience I often have, of being reminded of my former life as a boy and young man. Even though I live my life as a woman, just as I live my life as American, my imagination still conjures up and talks to the memory of the Filipino boy I once was.

When I find myself or others silenced or overlooked, I’m tempted to keep quiet because I know that’s what’s expected of me. That’s when I consult the self of my past, who tells me: “If you were still a boy, you would not allow yourself to be quiet.” And so I find myself speaking.

On days when I feel pressure to present myself in conventionally feminine ways simply to be noticed, that young Filipino boy tells me: “You don’t have to dress for anyone other than yourself.”

But to admit this — to say that having walked in the world as a man gives me strengths I wouldn’t have otherwise — is to open myself up to accusations that I am not really a woman now, that I have not been through the same struggles women who were born in their genders have been through. This, too, is so similar to how immigrants to the U.S. are accused of not being really American, and of profiting from the labor of people who were born in this country.

What these accusers refuse to understand is that whatever advantages I and other trans women have gained from our upbringing is more than offset by the challenges we face. But more than this, many of us use our experiences to champion the rights of women, precisely because we viscerally know the vast difference between how men and women are treated, in ways that those who have only lived as one gender cannot understand. Immigrants too have this same sense of comparison, a visceral gauge for valuing the different places we call home.

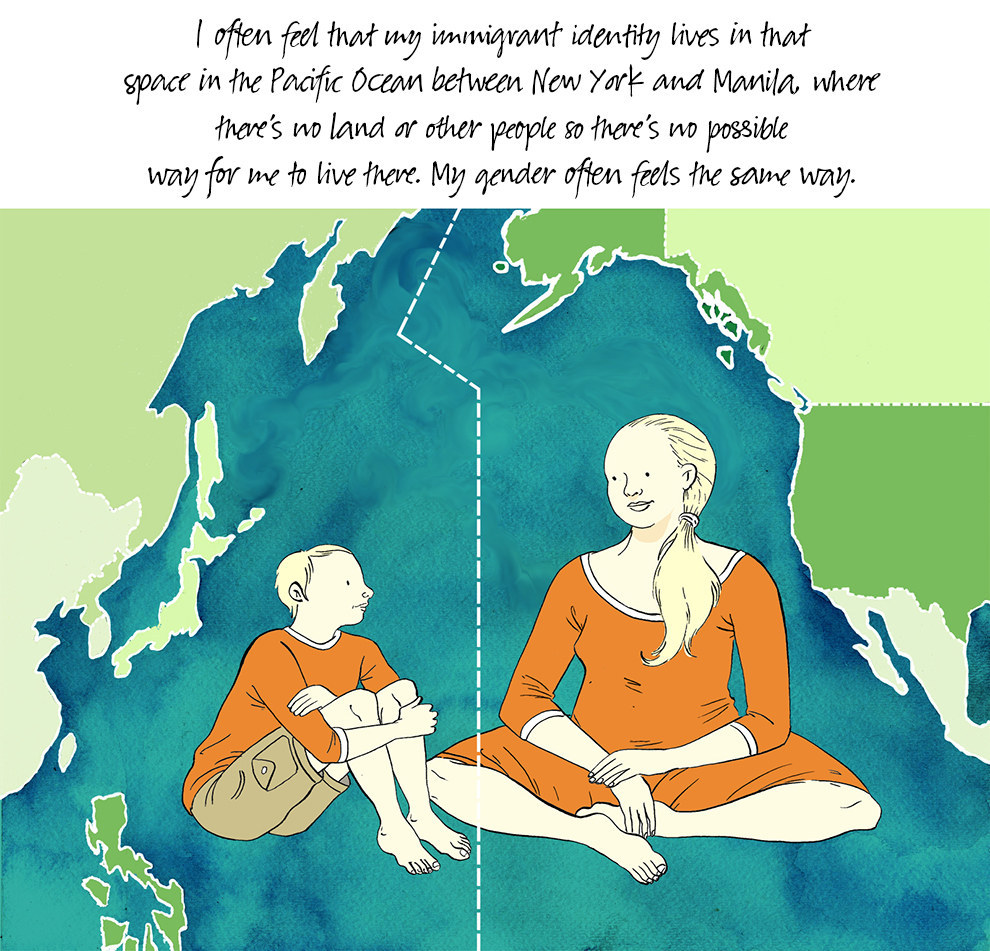

Whenever I feel persecuted or misunderstood, I calm myself by thinking of the ocean, because it’s the best way I can describe the gulf in my immigrant and transgender identities. I often feel that my immigrant identity lives in that space in the Pacific Ocean between New York and Manila, where there’s no land or other people so there’s no possible way for me to live there. My gender often feels the same way, lost in the societal expectation that my behavior and presentation have to be tied to one of two options, the country of man or of woman. These days, I’m more comfortable being American just as I’m more comfortable being female. But to the extent that it’s possible, the cherished aspects of my former country and gender continue to be part of my life, and I live in that space of possibility between homes.

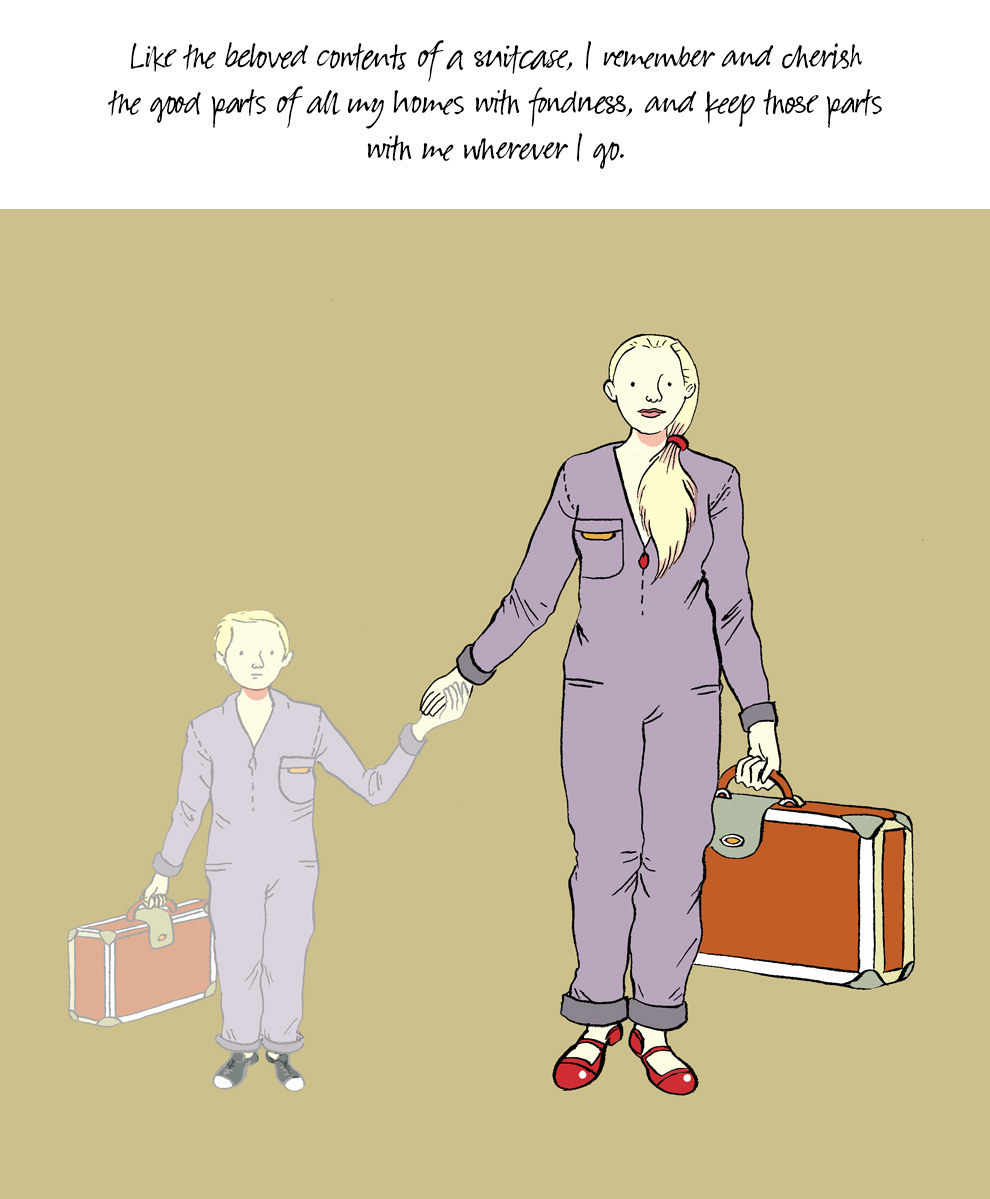

Despite the hardships, being a person who has moved from one gender to another has been a great source of strength, the same way being someone who moved from one country to another has. Maleness for me is a land I have no intention of permanently forsaking, but rather one that I’ve simply moved away from. Like the beloved contents of a suitcase, I remember and cherish the good parts of all my homes with fondness, and keep those parts with me wherever I go.