This past Saturday, hundreds of people poured into Robart’s Arena in Sarasota, Florida, to say goodbye to Edward Sotomayor Jr. — but a week earlier, his memory was celebrated in a quieter way, by the queer family with whom he was his truest self. The 34-year-old Sarasota native of Puerto Rican descent is perhaps the most recognizable of the 49 people killed in the Pulse shooting in Orlando on June 12. He was the first victim to be identified, his photograph shared thousands of times across social and news media in the frenzied hours after the massacre, and for many days that followed.

Inside a nondescript beige house at the end of a cul-de-sac, 15 minutes from downtown Orlando, about a dozen people gathered to say their goodbyes. This was a private memorial for Eddie — as his friends called him — not with blood relatives, but the friends in the community he’d been closest to, who considered themselves part of his chosen family. It was the first time they all gathered together since the shooting.

Among the small group of Eddie’s queer relatives, including some Pulse employees, were friends who had known the victim for over a decade, and had flown from other parts of the country to attend. Pulse’s entertainment manager, Neema Bahrami, a lightly bearded man of Persian descent in his mid-thirties, was their doting host. He had survived the massacre and helped authorities get people out, but his best friend hadn’t been able to escape. Neema called Eddie his “baby” and his “son”, even though they were practically the same age.

In Eddie’s queer family, parenthood transcends age and gender. He and others were known to call Neema “Momma” because of his caring demeanor and his tendency to adopt and mentor younger queer people. And if Eddie’s queer family counted Neema as their parent, then Pulse was that family’s home.

For many queer people, gay bars and clubs function as homes — sanctuaries tucked away from an oftentimes unforgiving straight culture. Many queers still keep their sexualities and gender-nonconformity away from blood relatives, and only express who they really are in chosen spaces like bars and clubs. Queer people around the country acutely felt that the attack on Pulse was an attack on LGBT people everywhere; they expressed their solidarity with vigils, posters at pride marches, and #weareorlando or #orlandostrong posts on social media. But for Eddie’s queer family, the attack was not merely symbolic — it was terrifyingly real and personal.

I found myself adopted briefly by that family. A friend connected me with Aurora Sexton, a trans drag performer who’s close with Neema; she had come to Orlando that week to perform at several benefits, and I joined her there. I had never been to Orlando before, but I found the LGBT spaces in this city to be the most inclusive I’d ever experienced — even after those spaces had been wracked by unspeakable tragedy. Here, a Puerto Rican gay man had considered a gay man of Persian descent his adoptive mother. In turn, both men counted trans women, queer women, drag queens, gay men, and other gender-nonconforming people — all of a variety of races — as good friends, which is common among queer people in the Orlando nightlife scene. The stark divisions that exist among members of the LGBT community in some other cities aren’t as much of a reality here. And if Orlando has become a national symbol of tragedy, it can also be a symbol of possibility — reminding us that longstanding factions within the queer community can and do unite. They did so in Orlando, even before a gunman opened fire.

“We didn’t have to make an effort to get people to come together,” a local gay pastor and friend of Neema’s said at the memorial. “We already knew what to do.”

Neema’s house, where the memorial was held, seemed blandly suburban from the outside with its shingled roof and vinyl siding, but the interior was more modern, with dark gray floors, leather couches, and cherry furniture. The house also had a big backyard, a pool with softly curved sides, and an open garage piled with boxes upon boxes of donations for Pulse employees.

On one side of the living room near the front door, several framed pictures of Eddie stood atop a high side table, surrounded by candles and an orchid plant with several white flowers in bloom, forming an improvised altar. One of the pictures was signed by friends, which Neema said will hang at Pulse when it reopens. The photo showed Eddie in profile wearing a black top hat, his signature accessory when he went out. He looked decidedly debonair and fun, in contrast to the brooding image of him in a button-down that’s been shared so widely on the internet.

After everyone had arrived, Neema asked the group to gather around. He told them that he and Eddie’s partner of three years, Luis Rojas, had met with President Obama the day before. Originally from Mexico, Rojas was at Pulse the night of the shooting, but had gone to his car right before the gunman opened fire.

“I was hoping Luis would be here,” Neema said, “but his family came today and they’re not from this country. They’re going to find out that he loves a man for the first time.” He went on to talk about how much Eddie loved life, and how he started wearing his top hat all the time when he realized how much attention it got him.

Earlier, Neema and others had talked about how they disliked the way news reports made him out to be such an angel even though he was salty and sarcastic. For his queer relatives, the established rituals of honoring the dead and emphasizing blood family have flattened Eddie’s life, highlighting only the most respectable parts of his story. This private memorial was an opportunity for Eddie’s queer family to remember him on their own terms, away from the expectations of others.

“Does anyone have anything to say about Eddie?” Neema asked with an impish grin that momentarily brightened his grief-stricken face. “For once, he can’t talk back.”

Laughter followed, then muted sobs. CJ, a trans woman and former drag queen who now works for a telecommunications company in Rochester, New York, looked around before raising her hand. She told a story about how she once went on a cruise with Eddie and a group of friends. “Eddie was just so outgoing and friendly and good-looking,” she said, growing more animated as she spoke. “It wasn’t long before he turned heads and got attention. These boys were just falling for him.” She talked about how Eddie would get together with members of the crew, only for him to ditch them a couple of days later for a different guy. “We just laughed at those boys,” CJ concluded, resolutely refusing to make him out to be a perfect man. “That’s our Eddie.”

Other stories followed a pattern: People had met Eddie through Neema, and he seemed mean at first, though they later realized he was being protective of his queer mom, who was a lot more open and welcoming. Laughter and sorrow continued to intertwine that night. Many members of this family — queer entertainers or club staff in Orlando and elsewhere — will keep working in the days and months following the shooting, keeping up the gay bars and clubs that are the sources of their livelihood, all of which have become symbols of resilience in the shooting’s aftermath. They’ll put on brave faces because it’s their job to serve other people’s needs. But here, in Neema’s house, they can let down their defenses and simply be there for each other – simply remember that Eddie Sotomayor was a real, actual person they loved, before he became a symbol of a tragedy borne out of hatred for queer people.

Two days before Eddie’s private memorial, most of the people there had to manage their grief in public, some of them while working. Southern Nights — another major club in Orlando that shares some staff and entertainers with Pulse — hosted a benefit on behalf of that club’s employees to make up for lost income while the club is shut down, featuring a bunch of drag queens and entertainers from across the country. There was a gargantuan line to get in, snaking around the club’s parking lot, as two security people scanned patrons with metal detectors and informed them that no bags were allowed.

Inside, before the show began, Neema spoke to the gathered crowd. He emphasized the club’s intention to rebuild in the wake of the tragedy. “When we reopen,” he stressed, “we’re going to be better, we’re going to fight, and we’re going to defeat all the evil that’s out there.” He emphasized determination in the face of tragedy, even as the prolonged hugs he received from hosts and staff as he left the stage hinted at his profound grief.

“You see queers of all stripes here, even before the shooting.”

The club seemed at once tiny and vast. Large numbers of people were packed inside the main space where the show was going to be. A sunken area with a stage in front of it was flanked with a bar on each side, one of which had a glass counter lit with a cool white light that made it feel both futuristic and retro, in a garish late-’80s kind of way. The club felt familiar, like so many other queer clubs — The EndUp in San Francisco, Escuelita in New York, or G-A-Y in London — dark places where people at the margins of society can let loose and be themselves.

But this wasn’t just any night at any gay club: There were large donation boxes at both the entrance and the bars, people selling raffle tickets to benefit victims, patrons hugging each other for comfort, asking each other if they knew anyone who died.

While hordes of people shifted back and forth as they waited for the show to start, it also became clear that the crowd was unusually mixed — so much so that it became hard to identify people’s individual places on the LGBT spectrum. There were the standard muscle gay boys, mostly white and some Latino. There were also femme gay boys and genderqueers, including a slim guy in a loose, shiny skirt with tights underneath. And there was someone who seemed like a drag queen in over-the-top, kabuki-inspired makeup, but was, judging by the pitch of her voice, a cis woman.

“You see queers of all stripes here, even before the shooting,” a woman next to me said when I asked her if this was typical.

One of the co-hosts, Roxxxy Andrews from RuPaul’s Drag Race and a former cast member at Pulse, announced that there were 40 performers over three sets that night. The show began and one survival anthem after the other played, from Kelly Clarkson’s “People Like Us” to Lady Gaga’s “Born This Way.”

Neema once again went onstage to introduce Blue Star. A lesbian performer and Pulse’s former entertainment manager, Blue continued to be friends with many of the club’s employees, and was known in the community as a tireless organizer in times of need. Neema described how Blue organized donations, provided phones for all the staff members who needed them, and got volunteers to put together care packages to deliver to the Pulse staff.

Blue came out to immediate cheers, wearing a simple, short black jumpsuit, her face nearly bare as her eyes glistened while she held back tears. Slim and blonde, she stood firm in a wide stance as she began the club anthem “One Love.” “I’ve been through the pain, I’ve been through the hurt.” Afterward, she moved through the crowd and hugged several people. Dozens of hands reached out with bills that she collected for a fund to help Pulse employees recover from the shooting. The audience instinctively knew that her relationship to the tragedy was deeply personal.

Yet Blue’s determined stance also held deep reserves of grief at bay. Earlier that day, I found her sobbing uncontrollably in the dark corner of the performance space she ran that functioned temporarily as a warehouse for donations, in an industrial area that the city is developing as a cultural zone, while Pulse and Southern Nights were a 15-minute drive away in the outskirts of downtown. She was playing a video on her phone that a Pulse employee had sent, thanking her for sending a care package.

“Pulse is my family,” she told me after she regained her composure. “There was no question in my mind I needed to help.”

After Blue’s performance, I exited the perimeter of the crowd struggling to see the show, and there was an immediate abundance of air and space. I found a white faux-leather couch next to the performers’ dressing room, where drag queens walked in and out.

“We’ll still be here after the cameras are gone.”

Melody Maia Monet, a trans woman of Puerto Rican and Colombian descent who had come to Orlando in 2011 to rebuild her life after transitioning in her late thirties, headed into the dressing room to visit a friend. Inside, there was a flurry of activity as queens inside got in and out of costume, some preparing on the floor because there were too many people. Maia, who became immersed in the Orlando queer scene as a singer and photographer, pointed out to me which queens were gay and which ones were trans (the former hadn’t made modifications to their bodies, while the latter had). The difference didn’t seem to matter much in the queer world of Orlando. Because most of the trans women performers started out as drag queens and still play that role onstage, their ties to gay people tend to remain even after they transition.

Chevelle Brooks, a black trans woman who was at Pulse that night but managed to get out, was exhausted and on her way home. Another trans drag queen, Nicky Monet, passed through to say hello. At the benefit, she was larger than life in a bright-pink sequined dress, bedazzled hoop earrings, and fake eyelashes, as she led a group of people in a gospel-inspired number. But in her tank top and jean shorts afterward, the trans woman with curly dark hair and light olive skin didn’t stand out in any particular way. She was a substitute performer at Southern Nights, and used to perform at Pulse.

Nicky made it clear, as so many queer people I spoke to in Orlando did, that the shooting was motivated by hate against queers. But more than this, Nicky was adamant that the shooter attacked not just gay but also trans people, even if to her knowledge, no one who died was trans.

“This isn’t just one shooter,” she added. “There wasn’t just the bullets that killed those people. There’s the bullet of last week, [when] we couldn’t pee in the right bathroom. There’s the bullet of being harassed and threatened on the street.”

Later, as I waited for a cab outside the club, Maia passed by with a large plastic garbage can to take to the dumpster, even though she wasn’t officially working that night. As the initial shock and grief after the shooting had waned, what remained was people’s different ways of coping.

Maia observed that for her, Blue, and many volunteers, physical labor was a way to get through the pain. She also felt that for people like Neema, focusing on the feelings of others allowed them to keep their own grief at bay. It was a process with no conceivable end date.

“We’ll still be here after the cameras are gone,” she said.

As I opened my cab door, Axel Andrews — a young, androgynous bartender and drag performer at Pulse who I’d been introduced to that night, and who had been trapped in a dressing room for hours during the shooting — came out of the club and waved. “Take care of yourself,” he said. “Be safe.”

On the following evening, in a quiet, intimate dressing room, away from the crowd and loud music outside, the current Miss Gay USofA, Aurora Sexton, was putting on her Miley Cyrus outfit. We were at Parliament House, a queer resort and club that was hosting another benefit for Pulse employees on their own regular Latin night. Aurora flew in from Nashville to help out, and had stayed up until 5 the morning of the shooting to make sure everyone she knew personally was safe, which they were, but friends of friends weren’t so lucky.

“It could have easily been our club,” Aurora said as she asked me to zip up the costume she had made herself, a white leotard that had two sets of zippers and a hook.

“I know the type of people who would want to hurt us,” she continued. “When you espouse hate speech, and when you repeat over and over that gay people are wicked, that trans people are predators and molesters and you scare people, it’s going to incite some of those people to violence.”

“I haven’t figured out what it all means yet. I just know I lost my friends.”

Aurora wanted to have one last drink before she performed. At the bar, she ran into her good friend Kristofer Reynolds, a muscular man with dirty-blonde hair and a goatee. He was a drag photographer who was on staff at Pulse for years before moving to San Diego two years ago, after a breakup. He said his pictures used to hang on Pulse’s walls, but he didn’t know if they were still there after the shooting. He’s close with many of the Pulse staff, especially Neema Bahrami.

“I haven’t figured out what it all means yet,” said Kristofer. “I just know I lost my friends.” Among the people Kristofer knew who died, he was closest to Eddie Sotomayor. But he still wasn’t sure exactly how many of the victims he knew, how many of them he photographed.

“I don’t know their names,” Kristofer said, “but I see pictures and I remember, He said hi to me once or, That’s the guy who asked me to take his picture.”

If Pulse is a queer family, it’s as though Kristofer’s brother Eddie died, but so did distant cousins, uncles, and aunts, people he encountered on occasion — maybe even danced with once or twice, but didn’t know particularly well. Knowing they’re gone, and that a club that was a second home to him for many years must be in shambles, has shaken him in a way he’s been unable to fully grasp.

“All I can feel right now is anger,” he said. “I haven’t had time to feel anything else.”

When Aurora came back to the common dressing room, she ran into Shantell D’Marco, a trans drag queen originally from Cuba who was a regular performer at Parliament House, and had come in to freshen up one last time before her number, wearing a salmon-colored pantsuit with sequins and giving off a Jennifer Lopez vibe. The two knew each other well from having performed together, and Shantell had once crowned Aurora at a gay pageant. Shantell talked about how difficult it’s been to work while dealing with the shooting’s aftermath.

“Did you go to a funeral today?” Aurora asked gently.

Shantell nodded, fighting back emotion. “Seven of my friends died,” she said. “I was really close to two of them.”

After her performance, Aurora returned to the dressing room to find Neema comforting one of the other queens who had performed, who was also a friend of Eddie’s. She was doubled over, sobbing. “I lost my best friend,” Neema said, presenting himself as a figure of resilience. He told her over and over again in different ways that they mustn't let the forces of evil win, and that they have to be strong. It’s what Eddie would have wanted.

After the queen calmed down, another staff member also started crying in the dressing room. Neema rushed over to hug him, as though despair were infectious and he was trying to prevent an outbreak.

Neema seemed resolute, though a witness told me he too had broken down after he spoke at a vigil two days after the shooting. Blue Star, the lesbian performer who’d been coordinating donations for the Pulse employees and was close to Neema, had needed to comfort him as he wailed. At that moment, it was Blue who performed the role of mother for Neema.

At 2 in the morning, when that night’s work was done, a small group gathered to head to the house where Kristofer was staying for some respite in private. Among them were Neema, Aurora, and a couple of other friends from out of town who had come to remember Eddie.

Neema volunteered to drive. As he stared at the road, he talked about how difficult it's been to relive that night whenever people tried to ask him about it. But among his close friends, he was able to talk about his gruesome memories: how the gunman laughed between bouts of shooting. How a water main broke and flooded parts of the club, so people who'd pretended to be dead had to come up for air and got shot. That one of the pulse employees hid under several dead bodies to survive.

The car turned from a major street into a quiet suburban neighborhood. Once the group had gotten inside the house and gathered around a formica kitchen counter, lit by the harsh glow of fluorescent lights, Neema opened the fridge and started taking out food.

“I’m a registered nurse,” he said, urging everyone to eat the pasta and biscuits he was serving,“but I started working at clubs because it paid better.”

The conversation woke up CJ, who had flown in earlier that day and left Parliament House early to get some sleep. After eating, Neema decided to go into one of the bedrooms to get some rest. The others followed and piled into the queen-sized bed with him.

“Don’t stop. If Eddie was here, he’d be the one to start.”

CJ, a large woman who spoke loudly and with expansive gestures, got up and started dancing around the dimly lit room in her red satin negligee; her breasts threatened to expose themselves at any moment. She had known Neema and Eddie for over a decade, back in the days when she was a drag queen herself. After her gender transition, CJ decided to stop performing and be more quiet about her gender history, though she didn’t let go of her longstanding ties to her queer family.

“I’m supposed to be in mourning!” she yelled.

“Don’t stop,” Neema told her. “If Eddie was here, he’d be the one to start.”

Everyone started egging CJ on to dance as she bent over lasciviously. Someone in the group of seven people started singing “Big Spender” from the musical Sweet Charity as everyone else joined in and laughed at lyrics like “I don’t pop the cork for every guy I see.” Then CJ licked her finger suggestively at the end of the song. Neema watched, smiling, but his eyes were vacant, even as several other people were laughing uncontrollably.

Abruptly, one of the men announced that he wanted to go to bed, and everyone fell quiet as he left the room. In the middle of the night, the revelry ended as suddenly as it began. They’d been determined to keep partying through their pain, but there were times when the burden proved too hard to bear. As the group dispersed, Neema got up and closed the bedroom door.

Pulse employees convened at Neema’s house after Eddie’s private memorial. As the house filled up, Neema instructed his guests to have some of the copious amounts of food piled in the kitchen — some of which he and his relatives had prepared, some of which had been donated — and to go and sit in the backyard.

Outside, a young Asian employee talked about going to the Victim Service Center, where the government and a number of companies offered help to those directly affected by the shooting. He talked about how a couple of airlines were offering free tickets to Pulse employees, so he was able to get one to New York to visit his family in a couple of weeks; he encouraged the other employees gathered around to go.

“We’ll be here a week from now, a month from now, six months from now, until you all get back on your feet.”

Neema asked everyone to come back inside, and as he took the floor to speak, he emphasized to the crowd of about 60 people that Pulse will reopen as an even better club. He chided Blue for being late when she arrived in a long summer dress and cornrows, and they bantered about her being a white woman with blonde hair wearing a black style. Soon, though, her tone turned both businesslike and somber. She discussed her and the local community’s commitment — especially that of queer entertainers and staff at other bars and clubs — to help employees and others affected by the shooting.

“We’re not just here until the cameras are gone,” Blue said. “We’ll be here a week from now, a month from now, six months from now, until you all get back on your feet.”

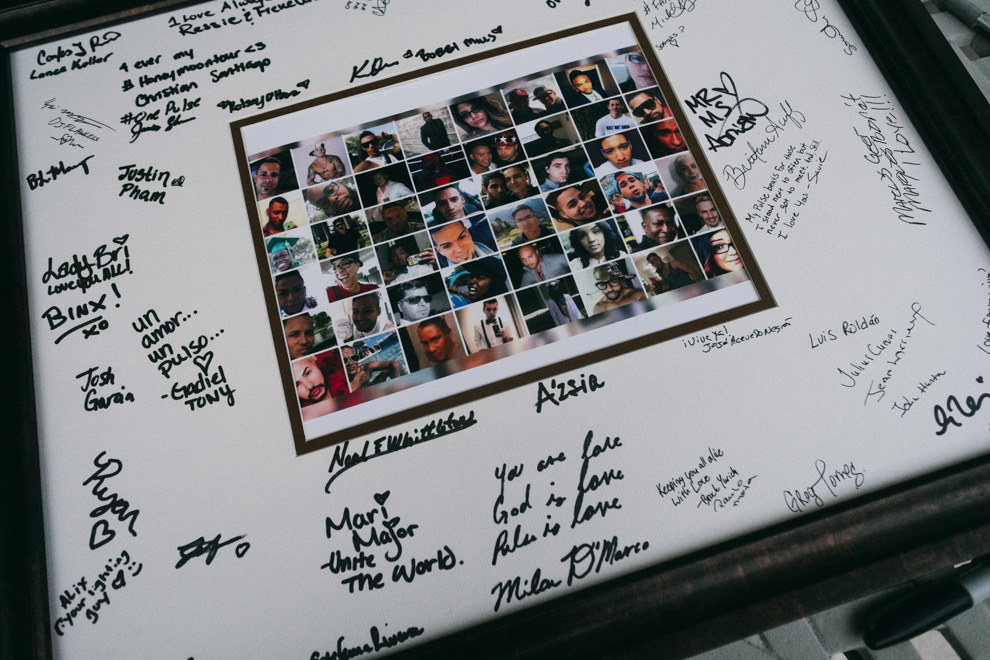

Neema brought out a framed picture of the 49 victims from the Pulse shooting, and told the employees he would leave it on a table outside for them to sign. But first, there was a group picture. As I headed outside with the group, a young black woman motioned for me to join them for the photo. I started to explain that I wasn’t connected to Pulse when she put her hand gently on my arm to interrupt.

“It doesn’t matter,” the woman said. “You’re family.”

After the picture, Axel came by to say hello.

“I hope you’re OK,” he said. “I know it’s a lot.”

Blue sat on one side of the pool, looking worn out from her efforts over the past week. After several days of focusing on fundraising and collecting donations for Pulse employees, she also gave a number of interviews to media outlets and performed in several benefits. She just nodded when I asked her how she was doing, as though the emotional and physical toll of the week was finally hitting her.

Everyone there clearly needed this time to grieve among people who had been to the club, who had been their friends before the most horrific thing that could possibly have happened to them came to pass. As much as I and so many other queer people have imagined and identified with what they must be dealing with, there’s no way to fully understand what it’s like to lose that specific friend or lover, that specific cherished sanctuary of a club — the one you’ve relied on as a home for your chosen family.

On one side of the pool, Axel and Blue each faced a group of friends, but occasionally turned their heads and glanced at each other. Neema watched as the Pulse employees came over and petted a group of docile comfort dogs that had recently arrived. As one mischievous golden retriever edged over to the side of the pool and put out his paws to get into the water, an employee scrambled to hold on to his leash to keep him from jumping in. Everyone started laughing and, for a brief moment, their gathering space was one of joy.