The first black officer to lead white soldiers into battle in the history of the British army. Britain's second professional black footballer. He was a man who overcame significant odds to achieve a huge amount in his short life. But almost a century on from his death, he remains a relatively unknown figure.

This is the incredible and ultimately tragic story of Walter Tull and his legacy.

Walter Daniel John Tull was born in Folkestone, Kent, on 28 April 1888. His father, Daniel, was a joiner who arrived in Britain from Barbados in 1876. His paternal grandparents had been enslaved.

When he was 7 years old, his white English mother, Alice, died, and his father married her cousin. Two years later, his father died. Tull and his older brother Edward were sent to an orphanage in east London, the Wesleyan Methodist Home, leaving his three half-sisters in his stepmother's care.

From their new home in Bethnal Green, Edward toured the country with the orphanage's choir, and during a visit to Glasgow he came to the attention of Jeanie and James Warnock, who were struck by his beautiful voice.

In November 1900 the Warnocks adopted Edward and he moved to Glasgow, leaving Walter, aged 12, alone at the orphanage. He joined the football team.

Tull and his brother grew up in a racist society where people of colour were deemed naturally inferior to their white counterparts, and fierce prejudice was the norm.

As a professional footballer he faced racist abuse from the terraces, and became an officer in the army despite official rules banning black officers from commanding white men.

Tull's biographer, historian Phil Vasili, said he was a man who preferred to be judged by his deeds rather than his words. "His moral compass was his Christian socialism, moulded by his Methodist upbringing. It provided guidance in his life. He had a developed sense of right and wrong and personally (and politically) he fought against injustice," Vasili, who's been responsible for much of the research into Tull's life, told BuzzFeed News.

Through his actions, Tull "ridiculed the barriers of ignorance that tried to deny people of colour equality with their contemporaries".

Tull's football career began in 1908 with Clapton, one of the best amateur sides in London. That season they won the FA Amateur Cup, and he caught the attention of scouts in the process.

He signed for Tottenham Hotspur in 1909, with a signing fee of £10 and weekly wages of £4. This was despite some misgivings over being a professional footballer – according to the Spurs club historian, Tull was considering working for a newspaper after completing a printing apprenticeship.

After touring with the team in South America he made his debut for Spurs against Manchester United the following season, becoming the country's first black outfield player.

In newspaper match reports he was referred to as "darkie", and he was racially abused by supporters in the grounds during his first games for the club. But he was also praised.

The Daily Chronicle hailed his "perfect coolness" and his "accuracy of strength in passing", remarking that "Tull is very good indeed".

Tull, another reporter wrote, was "Hotspur's most brainy forward...so clean in mind and method as to be a model for all white men who play football".

Graham Tutthill, a former chief reporter at the Dover Mercury, is related to Tull through his mother, Alice, something he discovered while researching stories for the Dover War Memorial Project in 2009.

He said stories from Tull's life showed his first cousin twice removed was, "despite his difficult start, determined to succeed".

"Becoming an orphan at such a young age must have been very hard. And then when he became a professional footballer, he had to endure very offensive comments about his race. But, as the newspaper reports of the time confirm, he rose above the insults and let his football skills do the talking," Tutthill said.

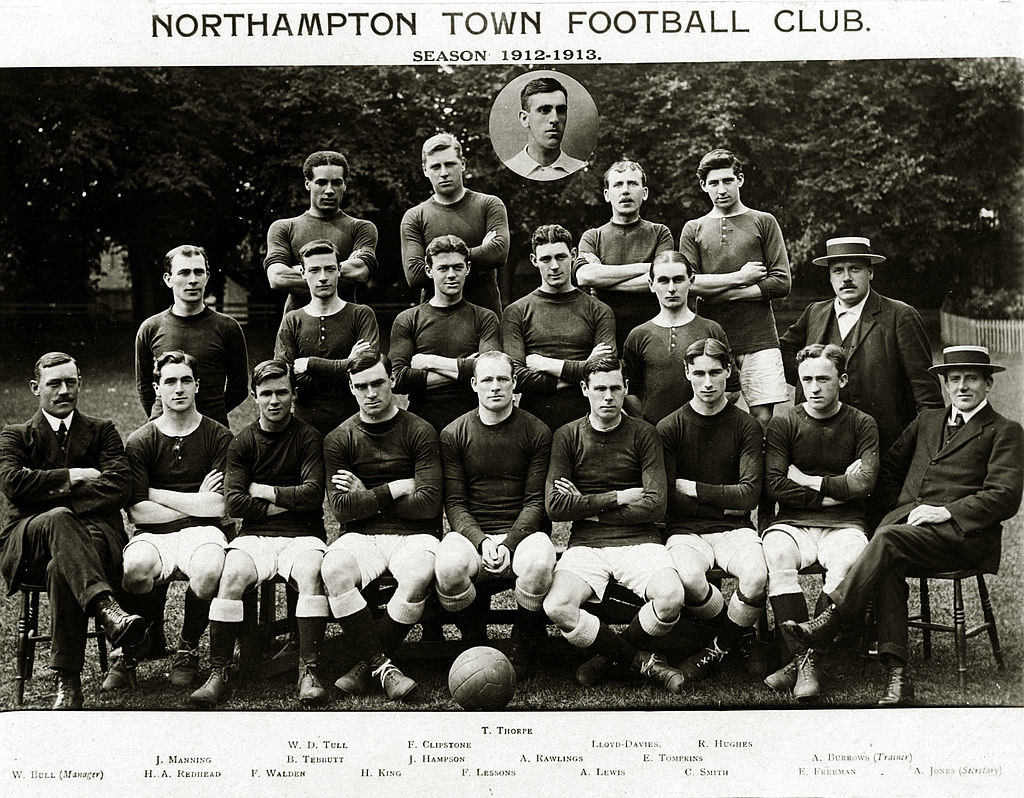

Over the next two years Tull played 10 times for Spurs, scoring two goals. Then in October 1911 he moved to Northampton Town as part of a transfer that saw another player move in the opposite direction.

Although he scored four goals in one match Tull found himself in and out of the team, the club's historian told BuzzFeed News. But a new manager changed his position to wing-half and he flourished in the new role, going on to make 108 appearances for Northampton over the next three seasons.

In the summer of 1914 Tull was preparing for the new season when Britain declared war on Germany. He was the first Northampton player to quit and join the British army – World War I had begun and Tull's professional football career was over.

August 1914 was also a very significant time for his brother Edward. For the past 14 years he had lived in Glasgow with Jeanie and James Warnock, the latter of whom was an unregistered dentist in the city.

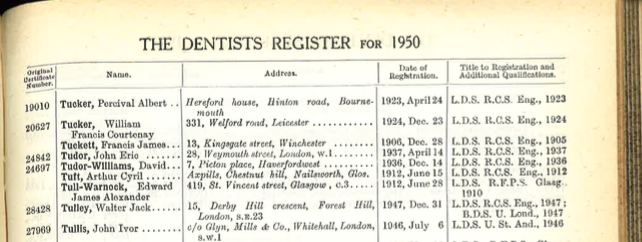

Edward followed in his adoptive father's footsteps and qualified as a dentist in 1910.

Arriving for his first job as an assistant in Birmingham, he was told by the dentist there: "My god, you're coloured! You'll destroy my practice in 24 hours!"

Edward returned to Scotland to work and in 1912 he officially registered with the Royal Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons in Glasgow. He had become Britain's first professionally registered black dentist.

When war broke out Edward's adoptive father died, and he assumed control of his practice. Dentists were in short supply in Britain at the time and few were ever conscripted into the army.

When Tull left football for the army he joined the 17th (First Football) Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment.

The regiment, nicknamed the Diehards, got its name from the high number of footballers who fought in it – its commander, Major Frank Buckley, had previously played for Manchester United.

In November 1915 the battalion was billeted in France, and the next year it fought in the Battle of the Somme.

The battalion's casualties were so heavy that it was disbanded, but due to Tull's courage and abilities on the battlefield, he was recommended as an officer.

Regulations in place at the time explicitly forbade people of colour being commissioned as officers: The manual of military law stated that candidates for commissions "must be of pure European descent, and a British-born or naturalised British subject".

Nevertheless, in 1917 Tull was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the British army. The second black British footballer had just become the first ever British-born black combat officer.

Second Lieutenant Tull joined the 23rd (2nd Football) Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment and was posted to Piave, Italy, and it was there he became the first black officer to lead white men into battle in the history of the British army.

Twice, on Christmas Eve and New Year's Eve, he led his company across the river in raids on enemy territory, and twice he brought all of his troops back safely.

Tull was again praised for his coolness, but this time it wasn't for his performance on the pitch, but for his "gallantry" under fire, and the words were not coming from a reporter, but a major general.

It was around this period that, while back in Britain for a short time, Tull signed to play for Glasgow Rangers when the war finished, partly so he could be closer to his brother. But their reunion never took place, and in 1918 Tull returned to France for what would be his sixth and final battle of World War I.

On 25 March near the village of Favreuil in Pas-de-Calais, Tull was shot through the head by a machine gun as he led his company in retreat during the last major German offensive of the war. He was 29.

Despite being under heavy enemy fire his company, including the Leicester City goalkeeper, tried to save his body for burial, but he could not be recovered.

With no known grave, Walter Daniel John Tull is one of the 35,000 soldiers' names listed on the Arras war memorial at the Faubourg d'Amiens cemetery in northern France.

In March 1918, Edward received a letter from the commanding officer of his brother's battalion:

Of course you have already heard of the death of 2nd Lieutenant W. D. Tull on March 25th last.

Being at present in command (the captain was wounded) – allow me to say how popular he was throughout the Battalion. He was brave and conscientious; he had been recommended for the Military Cross, and had certainly earned it, the Commanding Officer had every confidence in him, and he was liked by the men.

Now he has paid the supreme sacrifice; the Battalion and Company have lost a faithful officer; personally I have lost a friend. Can I say more, except that I hope that those who remain may be true and faithful as he.

For many years Tull's achievements were overlooked, and the impact he had on British society forgotten – in 1918 the British army was still rejecting black soldiers, and it would be 20 years until it commissioned another black officer, Vasili told BuzzFeed News.

But today he is being remembered, thanks in huge part to historians such as Vasili. His story was told in a BBC film and he featured on a £5 coin in 2014. There is a memorial to Tull outside Northampton's Sixfields Stadium, the road leading to which is called Walter Tull Way. Fans can even buy a beer named after him at the ground.

And Tull's story is just as relevant today as it ever was, Vasili said: "It is the story of a working-class black Briton who was erased from history – like many other working-class BAME people – because the past is written for us, not by us. His story means so much to me because it undermines and demolishes so many class and racial prejudices and conceptions hitherto seen as 'common sense'. His story should inspire us all because he embodies what it is to be a 21st-century Briton."

Tull died before he could receive the Military Cross he was recommended for, and despite the efforts of campaigners and politicians it has never been awarded to him posthumously. Vasili believes that Tull was never given the medal because he was a "legal contradiction" – a black officer in the British army.

Those calls for Tull to receive the award have never gone away either.

In a statement to BuzzFeed News, Northampton South MP David Mackintosh said Tull remained a role model for many people in the town, "not least for his achievements as both a footballer and as the first black officer in the British army".

"It is hard to imagine now the challenges he must have overcome due to the racial and cultural barriers of his time in order to serve our country," he said. "I fully support the campaign for Walter Tull to be posthumously awarded the Military Cross to make sure that this remarkable man receives his hard-won commendation that he so clearly deserves.”

David Lammy, the MP for Tottenham, described Tull as "one of the great black British heroes".

He said it was a testament to Tull's courage and bravery that he gave his life in the line of duty at a time when black men were officially barred from being officers, and some officers argued that black soldiers should not be enlisted into regiments at all.

"I have long called for Walter’s legacy to be recognised and I believe that he should be posthumously awarded the Military Cross – a fitting tribute given that a fellow officer has claimed that Walter was recommended for the honour during the war and questions still remain unanswered as to why he did not receive it," Lammy told BuzzFeed News.

“Everyone should know about Walter, and honouring him in this way would raise awareness of his story whilst also serving as an important reminder that men of all races, creeds, and colours sacrificed their lives in both world wars.”

Tull's relative Tutthill said his story was both relevant and inspiring to anti-racist campaigners in football today, and young people in general.

He said when the school Tull attended as a boy in Folkestone built a new sports pavilion and asked pupils to suggest names for it, the winning suggestion was the Walter Tull Pavilion. "It is good to know that today's youngsters are so interested in Walter and inspired by him," he said.

Tutthill said it was "unjust" that Tull never received the Military Cross: "Perhaps, sadly, [it] is still a reflection of the prejudice which he encountered during this life. Thousands of people have supported the campaign for the award to be made posthumously, and it would be very fitting if the award could be made by, or even on, 25 March 2018 to mark the centenary of his death.

"All his relatives, and others who have been involved in the campaign, would agree that it would be a fitting tribute to such a brave, determined, and well-respected man."

Vasili added: "Institutional racism stopped the Military Cross from being pinned to his breast. It suited the army to make him an officer after the Somme because there was an acute shortage of experienced soldiers after the slaughter.

"The government would now rebalance the scales of justice in Walter's favour and right an historic injustice. And say sorry!"