Woman, Actually is the little corner of BuzzFeed where Mariela Summerhays writes about everything and anything to do with being a millennial mother — a woman first, mother second. Yes, you'll read about the glorious struggle and joy of child-rearing — but also about relationships, mental health and more. Because as it turns out, growing up doesn't stop at motherhood.

MY YOUNGEST DAUGHTER is so beautiful, ask anyone.

She has long black hair, darker than those of her older brother and sister. There's this tiny birthmark that dots the corner of her mouth, like a line from J.M Barrie’s Peter Pan, my very favourite book — “her sweet mocking mouth had one kiss on it that Wendy could never get, though there it was, perfectly conscious in the right-hand corner”. It looks like the giveaway sign of a chocolate sneaked into her mouth before dinner.

And she has her father’s fair skin — which painfully, many people marvel at, including myself.

Painfully, because she also has my mother’s blood and my father’s. And their parents’ blood, and theirs before them. Because from her father’s side, she may be the granddaughter of a tall surgeon with blue eyes and kindness in his hands — but she is also the granddaughter of a first generation university graduate, with her entire family’s survival on her shoulders.

I hate the possibility that my daughter would ever be made to feel more proud of one half of herself than the other, especially when her Asian heritage doesn’t so readily show itself in her face. I just don’t know how to make sure she doesn’t forget what I don’t fully know myself.

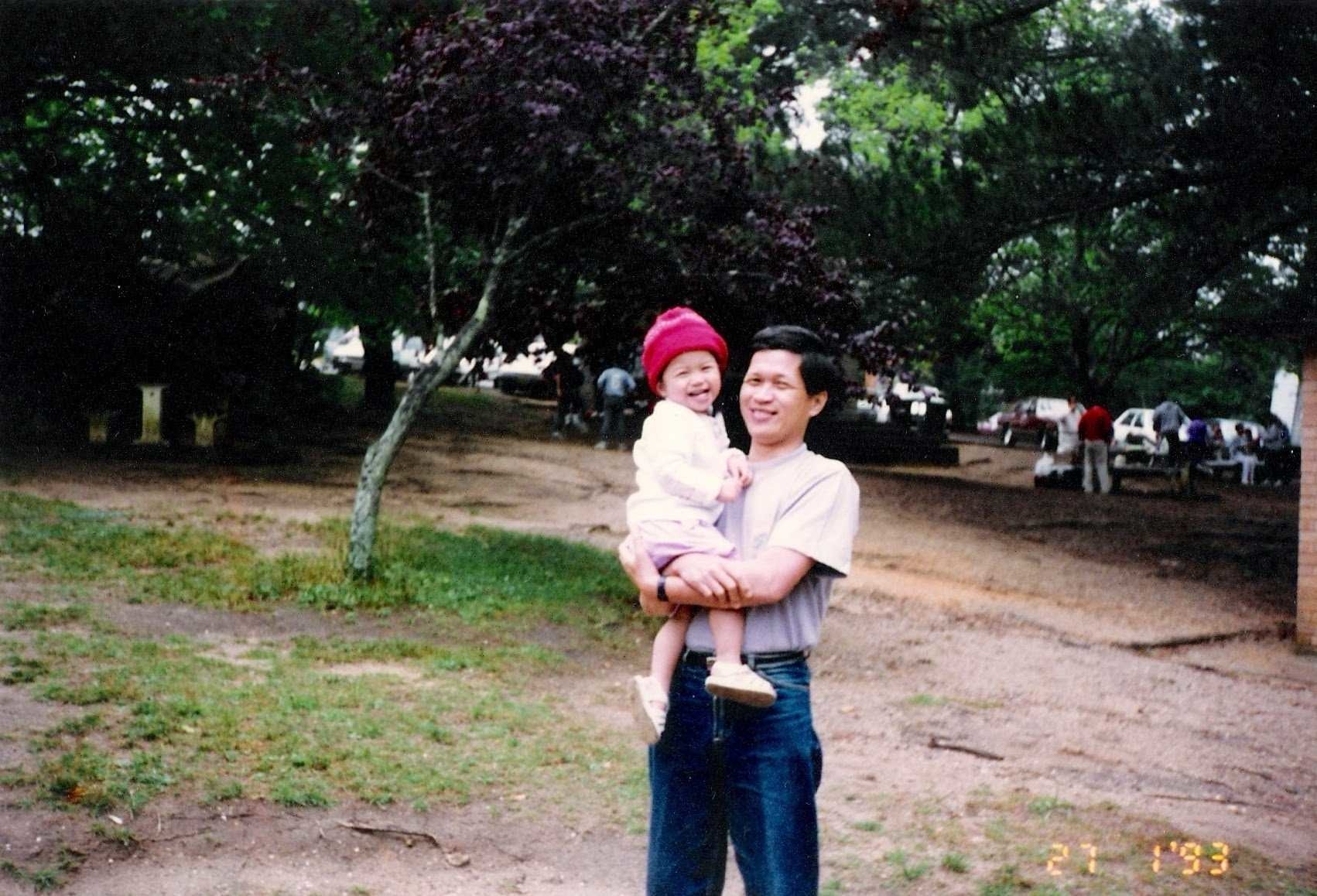

I AM THE DAUGHTER of Filipino immigrants. Like most people who come to this country from a developing nation, they brought generations of expectation and a history of struggle with them, tucked into a passport that opens less borders to them than the one with which I was born. Arriving a couple of short decades after the White Australia Policy was officially abolished, my parents’ generation often put away essential parts of themselves to prosper here. My sister and I were spoken to in English, my childhood brimming with the Western tradition of film and literature. I ate the Aussie staple of spag bol for dinner, at least twice as many times as pancit, the Filipino method of serving noodles.

I have no hesitation in committing to words that I love this country. Sometimes it feels like a shameful secret, because Australia is flawed in so many painful, obvious ways that has deeply hurt the people I love, to people who look like me and beyond. But I owe my education, my freedom and the end of a cycle of poverty that until a generation ago, was my fate. So my children’s Australianness, between my Irish-Australian husband and myself, is lovingly nurtured.

Still, I’ve been thinking of how to pass on my own heritage to my children. In the few places art addresses these feelings of in-betweenness, the salve for the protagonist is in the language or food that forms a connection between them and their ancestors’ homeland. The closest I felt to identifying with a story growing up was Melina Marchetta’s generation-defining Looking For Alibrandi — and even Josie knew how to make tomato sauce from scratch.

However, with only good intention, my parents prioritised giving me the full use of the English language at the expense of their mother tongue, and I cannot teach Tagalog to my children. I do not cook — so my children cannot identify adobo from any other stew my husband might cook on any given night. And in my youngest daughter’s case, does not even resemble the people from whom she comes.

IN A WAY that is not immediately obvious to those around me — including to friends who joke with no ill intention, but perhaps misplaced levity, about my being "the whitest of Filipinos" — and even to myself, there are aspects of my parents’ culture that I do know. I know because it is in my blood, it is my birthright. And it's caused me to decide I do not need to prove I am Filipina, any more than I do that I am Australian.

It is in whenever I decide to succeed — and by a definition I get to determine for myself — because I may be one of the first in a long line of women to have the freedom to do so, but because of my parents, I won’t be the last.

And I feel it my honour to continue what my parents have begun, this bringing our family line further from poverty to physical and spiritual prosperity. My children may reject this endeavour, may grow up to not consider legacy — that alone is a privilege that has been won by my parents, whose every decision has been made so future generations have the possibility of self-determination.

I hope to know more of my parents’ first language. My children will eat at least as much pancit as they do spag bol. But if those best of intentions never come to pass, I know there is nothing I can give my children that wasn’t already theirs to take, as determined by their grandparents.

My youngest has her paternal grandparents’ wicked humour, good nature and fair skin; but make no doubt, she is Filipina, too.