In the late seventies, Lyn Fraser was walking from the West End to the Valley in Brisbane. She was with a girl – just a friend – and they were on their way to a gay club. And then a car pulled up.

"These young men pushed us over and called us names, ‘dyke,’ ‘lesbians,’ and other names… I think it’s being called a ‘lesbian’, which is not a big deal now, but at that time it was such a big deal to be called any sort of name like that, a homosexual name. And then they drove off. We didn’t end up going to the club because I was too scared. I backed off. I went back into the closet."

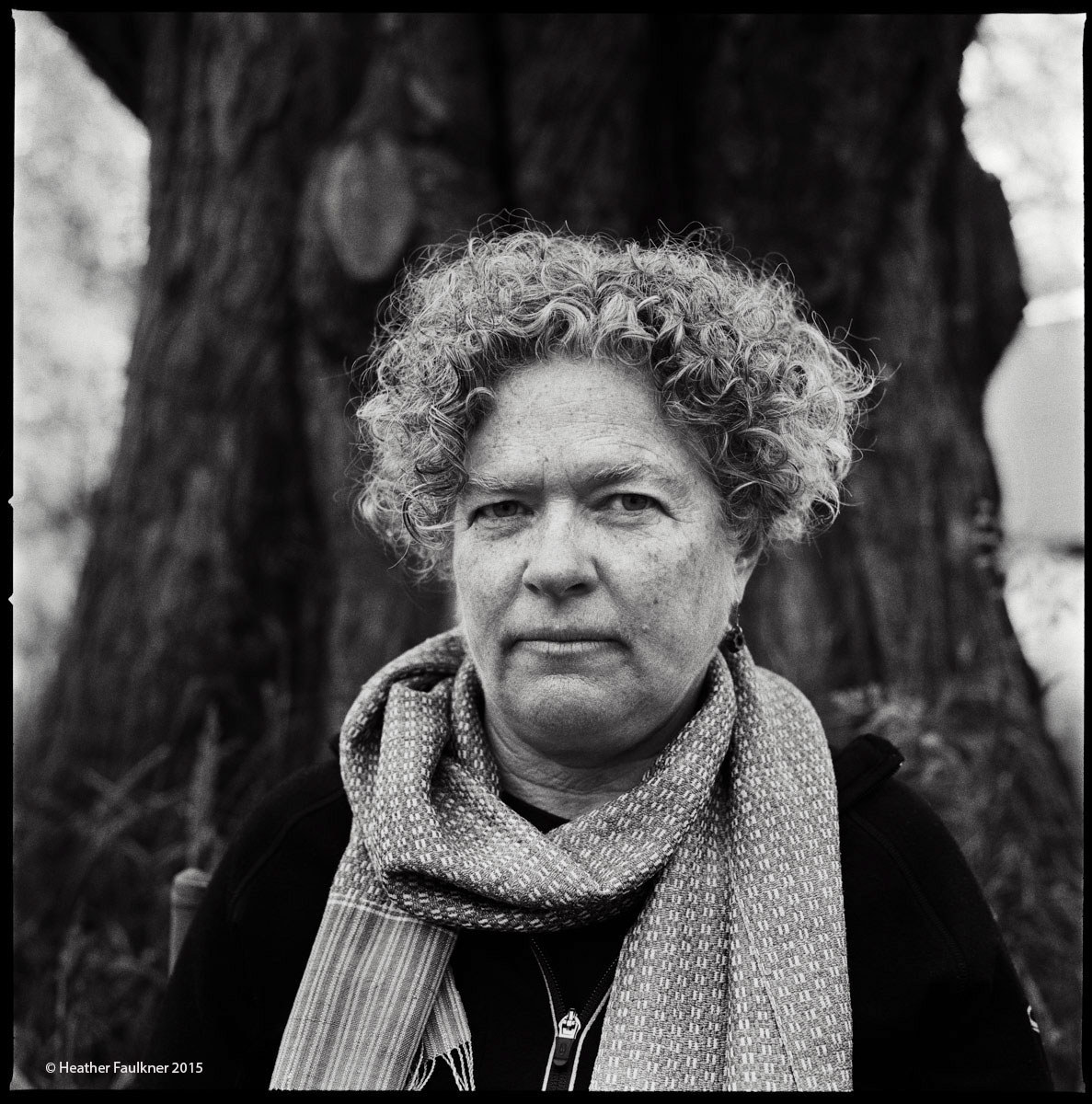

Fraser's story appears in North of the Border, by cross-media storyteller and documentary photographer Heather Faulkner. The book, a follow on from Faulkner's PhD research project A Matter Of Time, combines interviews with photography to tell the stories of eight lesbians who grew up in Queensland, aged from their mid-fifties to their mid-seventies. Faulkner hopes it will fill a hole in Australia's LGBTI history.

"What I intend for the book to do is to give older lesbian and gay readers a sense of agency that their stories are important," she tells BuzzFeed News over the phone.

"That they’re honoured, they’re respected and they’re recognised."

The eight women featured in North of the Border lived through Joh Bjelke-Petersen's three-decade-long reign as Queensland premier, a time renowned for its deep conservatism. It's this period of history that Faulkner wants to tell – and for the first time, from a lesbian perspective.

"As much as you can say it was the most politically conservative or even authoritarian state – some academics have come out to say it was the most authoritarian state in Australia – it was also the most radical state," Faulkner explains.

The control exerted by the state, particularly over demonstrators, provoked activism and solidarity from marginalised groups, including Indigenous Australians, women, gay men and lesbians.

"There’s a connotation of Queensland being like the Deep South. That’s true to the point that it was stigmatised from the outside as being this backwards, backwater place, but the reality was that internally it was this incredibly vibrant state."

"It was the most radical and the most conservative."

“More and more I realise how important the solidarity of the group is and has been in my life – the solidarity you can build together. One of the things we did in Brisbane was to live in group households. Groups of women, feminists and lesbian-identified women, sharing homes together, sharing lives together, sharing kids together… That way, you’re in the business of creating the world you want to be in. My daughter had these wonderful experiences of being raised by any number of fantastic women – strong women, interesting women. The boundaries in the households were very blurry, particularly around relationships including sexual relationships – it was a ‘never sure who you’d wake up with, who’d be in bed with whom the next morning’ kind of thing. There was a lot of fun but a lot of angst as well. But times you wouldn’t regret.” - Carol Low

But even though there were strong communities, the ramifications of discrimination run deep, says Faulkner. When she tried to find gay women to be in the project, many Brisbane "OWLs" (older, wiser lesbians) were supportive in theory, but too scared to put themselves forward.

Some cited fears of employment discrimination, others of the response from their families, says Faulkner. Some just hadn't come out.

"All those old fears that were realities in the fifties, sixties, seventies, eighties, are still compounding the way they go about being in the 21st century."

In the end, Faulkner only found eight women willing to go on the record.

"It’s a very big call [even] for a person who hasn’t experienced any discrimination because of their sexuality, but it’s much more compounded and scary for people who carry that history around with them."

The candid stories in North of the Border reveal how lesbians coped in the face of a hostile society – how they negotiated that time to find a belonging for themselves, as Faulkner puts it.

Mel, another woman in the book, lived with her girlfriend in Cairns in the sixties.

"They were living in a kind of clandestine relationship, the girlfriend would go out on dates with men but come home to Mel," explains Faulkner. In a technological mishap almost unfathomable to today's youth, they were caught out saying "I love you" to one another on a "party line", a public phone call where others could – and did – listen in.

"They got busted, and one night they had just come home from the drive in theatre and were getting ready to go to bed and there was a loud banging on the door."

It was two men they knew from work, drunk and angry.

"One started man-handling Mel's girlfriend and the other started berating her for not having enough beer in the fridge," says Faulkner. "She got really angry to see this other guy manhandling her girlfriend and she picked up a knife, and lost it, and the guys took off before she could hurt them."

After that, Mel and her partner decided they couldn't stay in Cairns – but instead of moving to the city, they took off to the Gulf of Carpentaria.

"The strange thing about Mel and her girlfriend was that they had to leave a bigger city to go to a very tiny town where they could actually live openly," says Faulkner.

"It sort of goes against the generalisations of LGBTIQ history, like you’ve got to go to the big smoke to come out... There’s little pockets of queer Queensland all over the place, in the strangest of places all of a sudden there’s a little rainbow flag."

“I never felt that it was necessary to make any sort of statement. It was pretty obvious what I was. I wasn’t the seventies’ Kylie Minogue, looking gorgeous and cute in a little froufrou thing. I was a sweaty, in-your-face rock singer, singing about taking women to bed. How more out do I need to be? I came out wearing sequins on my nipples and not much else with a fur cape. We had the number one song, 'A Matter of Time'. We’d blown Suzie Quatro out of the water.’ It certainly had fringe benefits being the lead singer in a rock band. Access to certain women – that made up for the financial shortfalls… My career, I am told, could have been enhanced had I been obliging in a heterosexual way to one particular record company executive. Years later I ran into him and he said to me, 'you know Lloydie, if you’d have been straight and you’d have played the game, you would have gone a lot further.' I thought, well, praise be to that. I’m happy to be where I am.” - Carol Lloyd

Faulkner likens the sporadic queer oases to the HBO series Deadwood.

"If you think of a town like Deadwood, a town of people with mysterious pasts, where everyone’s got a past but nobody asks about the past and they all just get along. But they’ve all got their little kinks and idiosyncrasies."

"There were pockets of towns like that in Queensland – not a lot – but there were places like that where all the misfits lived together in sort-of harmony, in a sense. At least they didn’t kill each other."

To put together the book, Faulkner spent a week or two at a time living with her subjects, photographing them in situ. She wants North of the Border to counter established narratives about Queensland, lesbians, and the queer community at large.

"It breaks apart that generalised narrative that a lot of people have about lesbians or the LGBTIQ community, that we all vote one way, we’re all vegetarians, we wear Birkenstocks, etc."

Faulkner has turned to crowdfunding to find the money to publish North of the Border and go on a speaking tour, with money also coming from the Centre for Creative Arts Research at Griffith University, potential grants, and out of her own pocket.

She says when she started her PhD project, A Matter of Time, she had the aim to "make these stories accessible to people, always".

"My experience is that books about lesbian history don’t usually get a second print run, and they become obscure and hard to find." Same with films, she adds, recounting a tale of watching a degraded, fuzzy VHS copy of Forbidden Love in the state library of Queensland – shunted into a private booth because of the "lesbian content".

Faulkner wants to spread the stories collected in A Matter of Time across as many mediums as possible. She had a 2013 photographic exhibition in Brisbane, now North of the Border, and maybe a documentary or graphic novel in the future.

"I wanted to keep it moving, keep it breathing, disseminate it in as many different ways as I could."

“With my mother, I remember taking home someone from the household who I was kind of involved with. And my mother spending all night crying, “you are. I know you are. I know you are. You are.” And me going mute. I cannot speak. I’m so in shock. Over the years she’s kind of adapted. She can now ask, “how’s so and so, how are they going?’ But she won’t stay ‘cause of the trauma of staying in the lesbian domestic space. So she will stay in a hotel or something when she comes to visit. Coming out – it’s like you embody something as you are walking around your identity in costume, in hair, in the way you are, in who you’re with, so you’re always coming out and coming out in workplaces. I usually wait. I never announce it.” - Ros Prosser

"There’s a lot of different avenues for the book to do good, especially teaching younger people about what it was like back in the day," Faulkner says.

"We weren’t just worrying about marriage rights, we were worried about the right to walk into a bar or hotel because there was an anti-deviant law. Or you weren’t allowed to be served, or you weren’t allowed to walk down the street with more than one friend because you could get arrested, or you would get beaten up on the street for no reason whatsoever."

The women featured in North of the Border share astonishing stories of fear, community, and survival. Lyn Fraser's story of harassment en route to a gay night out is just one example of the climate in which they grew up and came out – or didn't.

"We all hid. It doesn’t make you want to come out even if you were out to yourself," Fraser, who now lives in far north Queensland, says in the book.

"I love this state – do not get me wrong. I love Queensland to bits. I don’t want to live anywhere else in the world, I think it’s wonderful. But at that time we were four million years behind everything else, everyone else."