On the morning of August 10, 2015, 66-year-old Alan Bugden arrived at Royal North Shore Hospital for an appointment to manage his diabetes. He entered a single stall toilet, where he suffered a stroke.

He wasn't found until about 20 hours later, at 6.20 the next morning, when somebody came to change the stall's sanitary bin. Bugden, who was at that stage still alert and making eye contact but unable to speak, died later in the hospital.

A year and a half later, on the morning of December 19, 2016, 25-year-old Amaru Bestrin entered a disabled toilet on the ground floor of Liverpool Hospital. Inside, he injected heroin, which fatally reacted with the clonazepam Bestrin had taken for a flight home from Chile the previous day. He was found dead by cleaners almost 12 hours after he entered the toilet.

The two deaths involving people lying undiscovered for hours in public hospital toilets are being examined together in a coronial inquest that began in Sydney on Tuesday.

Deputy state coroner Harriet Grahame is looking at how it came to be that Bugden and Bestrin were not found for hours, and what measures could be implemented to stop it happening again.

Counsel assisting the coroner Kirsten Edwards told the inquest that Bugden had been feeling good about his health the day before the appointment and didn't think he needed to go. But his wife Lexie Bugden urged him to attend, saying it was important to be proactive about his health.

This approach “should have saved his life”, Edwards said. “But because of an appalling and tragic set of circumstances, he didn’t leave the hospital alive.”

A number of factors led to the delay in finding Bugden as he lay in the toilet cubicle, the inquest heard.

As a visiting outpatient, he was not signed in at the hospital, and as a result, when his family, and then the police, rang up looking for him, the switchboard told them he wasn't registered as a patient.

A number of cleaners had attempted to clean the bathroom, but left after seeing it was occupied. None of them told the supervisor they had been unable to clean it, and none were aware of any requirement to do so. No-one noticed that the toilet was still locked when the Ambulatory Care Centre was closed up at the end of the day.

Edwards said Bugden had "had some level of consciousness for 20 hours and couldn’t call for help".

Dr Geoffrey Herkes, who treated Bugden before he died, said by the time he was found it was too late to give him the emergency "clot-busting" medication that can be administered to people in the first four-and-a-half-hours after they suffer a stroke.

"By the time he was found he had signs of an established stroke on his CT scan. That precluded the use of any so-called 'clot-busting' medications,” Herkes told the inquest.

The cleaners were very busy on the day Amaru Bestrin died in the disabled toilet at Liverpool Hospital, and nobody had tried to clean the toilet between 1.30pm and 10.30pm due to an unusually large number of requests.

There was no procedure in place at that time for cleaners to escalate the matter or notify somebody if they couldn't clean a toilet. And like Bugden, Bestrin was not registered as a patient at the hospital.

The inquest will hear expert evidence that most opioid deaths don't occur immediately, Edwards said. It is unknown how long Bestrin had been dead when he was found.

The inquest heard that there had been seven deaths over 18 months relating to people dying or collapsing in hospital toilets.

In December 2016 every local health district in NSW was ordered to put in place “clear inspection and escalation procedures” for cleaning and clinical staff, a spokesperson for NSW Health told BuzzFeed News.

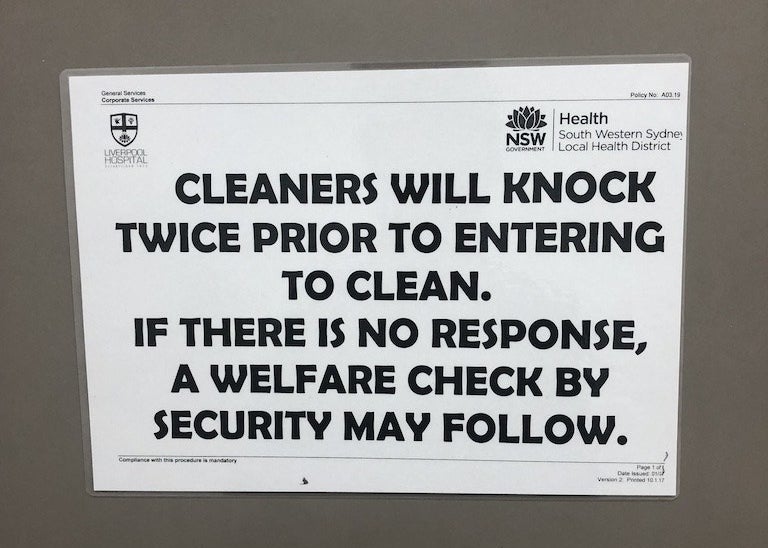

Cleaners now have to knock on occupied toilet doors, and if they have any concerns about the occupant – for instance, no response – to alert hospital or security staff.

There’s extra signage in public toilets in hospitals, and systems have been introduced for recording which toilets have been cleaned and inspected, and when.

There have been no deaths since this memo was issued, Edwards said.

According to the department, that is the best evidence that the policies have been effective, however it's unknown how many "near misses" there have been, when people have collapsed but received medical treatment in time.

The inquest also heard from Bestrin's mother, Lorena Bestrin, who described the disabled toilet where her son died as an "unsupervised injecting room" and called for a medically supervised injecting room in Western Sydney, as there is in Kings Cross.

She said Liverpool Hospital's clean needle dispenser, which Bestrin is thought to have gotten syringes from before injecting, is a good harm minimisation program, but it is a "job half done".

“We’re providing the needle, I understand that," she said. "But if we’re providing them with a safe environment where they could do it safely and supervised, my son’s death would have been prevented.”

The inquest will look at toilet building and design issues, including emergency duress buttons, which were in neither of the toilets Bugden and Bestrin were in. It's unknown whether either man would have had the capacity to press a duress button after they took ill.

It will also look at toilet door design. Both Bugden and Bestrin were in single occupancy toilets with a floor to ceiling door, as opposed to a cubicle door with a gap at the bottom and top.